When the River Ran Red

Arthur Kemp, American Renaissance, September 2008

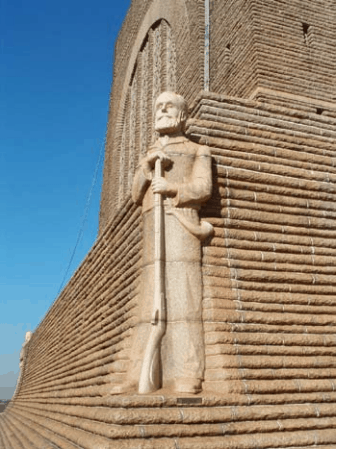

Statue of Piet Reteif at the Vortrekker Monument in Pretoria

The year is 1838. Dodging a flurry of spears, the Boer commander, Andries Pretorius, rides forward to seize a Zulu warrior. In the midst of an epic battle between more than 15,000 warriors and just 468 Boers, Pretorius has decided to take a Zulu alive. He wants to send the captive back to his king, Dingaan, to convey surrender terms to the Zulu nation.

The warrior has no intention of being taken alive, and jabs viciously at Pretorius with his assegai. This is a Zulu spear, normally a long-shafted throwing weapon, but the warrior broke its shank earlier for close-quarter stabbing. Pretorius gives up on capturing the Zulu, and tries to shoot him.

With a single-shot, muzzle-loading musket, he has only one chance of a hit. There is no time to reload in close combat. To his horror, Pretorius sees the smoke-trailing ball whiz past the Zulu’s ear. At the same time, the Zulu lunges forward, causing Pretorius’s horse to stumble backwards, throwing the white commander to the ground.

Leaping to his feet, he meets the attacking Zulu, who knows he is now on equal terms with the white man, who can no longer use his magic shooting stick and carries no weapon comparable to the assegai. Pretorius is now fighting for his life. He just manages to sidestep the spear point, striking it away with the butt of his gun.

Spinning round, the Zulu raises his spear high above his head and thrusts down, as he has been trained to do in the Zulus’ disciplined army. It is a blow that will be fatal if it strikes home, but Pretorius sees it coming. He grabs the spear point with his left hand to ward it away from his chest. The sharp point cuts deeply into his palm, embedding itself at an angle that makes it impossible for the Zulu to pull it out. Pretorius seizes the Zulu by the throat with his free right hand and throws him to the ground in an attempt to strangle him.

The Zulu struggles, and with the help of two good hands is about to break free, when one of Pretorius’s men comes upon the scene. He pulls the assegai out of the commander’s hand, and plunges it into the Zulu’s side, ending the struggle.

Pretorius remounts and heads back to the Boer camp for treatment. He is not worried, as he knows by now that this greatest of all battles between Boers and Zulus has already been won. The main Zulu army has been broken in two, and the river that runs along one side of the Boer camp is stained red with Zulu blood. The place and the tributary known previously as the Ncome will be renamed Blood River. Pretorius knows that the Zulu defeat, which will include some 3,000 killed on the battlefield, is a fit revenge for the deception and murder committed by the Zulus 10 months earlier.

Andries Pretorius

Prelude to War

The great clash between the Boer and Zulu nations was not, as leftist historians like to claim, the result of ruthless white colonialism suppressing an indigenous people. It came about because the Zulus rejected an extremely reasonable attempt at negotiation by the Boers.

The Boers, pioneers of Dutch, French, and German descent, were the people who opened up much of what was later to become South Africa. Their first antecedents had landed on the southernmost tip of Africa in 1652, only 45 years after the Virginia Company settled on Jamestown Island.

When they arrived in the area now known as Cape Town, whites came into contact only with Hottentots and Bushmen. As the number of Europeans increased, they expanded east and north, only meeting their first black tribe, the Xhosa, some 500 miles away, on South Africa’s east coast. The Xhosas were migrating south, fleeing the warlike Zulu to the north, who were engaged in imperialist expansion of their own.

For just under a century white settlement halted at this eastern frontier border formed by the coast and firm Xhosa settlement. It was not, however, a time of peace, as Xhosa were constantly raiding the Boers who lived on the border. This caused much harm and discontent among the farmers, who blamed the Dutch-ruled colonial government back in Cape Town for the lawlessness.

It only added to the border farmers’ grievances when the British took the Cape Colony from the Dutch in 1806 to prevent the colony from falling into French hands during the Napoleonic Wars. It was vital to control the merchant and naval refitting station on the way to the Far East. The new colonial masters not only started anglicizing the colony, when they abolished slavery they offered compensation that amounted to hardly a quarter of a slave’s value.

Exasperated by incessant Xhosa attacks and British attempts to suppress their language and culture, groups of frontier farmers, filled with a sense of manifest destiny not seen again until the opening of the American West, set forth to the north and the east in a movement known as the Great Trek. The trekkers (they became known as Voortrekkers, or pioneers, only after 1880) bypassed the Xhosa in search of new, unsettled territory, in which they could establish independent Boer nations. All told, it was only a small minority of no more than 12,000 Boers who made the trek to the future Natal, Orange Free State, and Transvaal regions. They traveled in several waves of covered, ox-drawn wagons much like the Conestogas in which Americans opened the West.

The Boer leader of the time, Piet Retief, had written the trekker “manifesto,” in which he spelled out the farmers’ long-held grievances against the British. By1836, the Boer wagons had crossed the great mountain range into Natal, in an act of audacity that few thought possible. The range, the highest in southern Africa, had been named the Drakensberg — the Dragon Mountains — because they were said to be impassable.

Retief had identified a large piece of uninhabited land to the north of the Zulu kingdom, which lay open to settlement. Retief knew that if he wanted the land for his people, he could take it unopposed. However, he wanted to live in peace with his Zulu neighbors, and before taking possession, he opened negotiations with the Zulu king, Dingaan. He wanted no misunderstanding between the two peoples.

He sent a letter to the Zulu king explaining why he wanted to speak to him, and first visited Dingaan’s capital — a large circle of reed and grass huts — on November 5, 1837. Retief left the main body of trekkers and went to the Zulu king’s capital, Umgungundhlovo (“the place of the elephant”), to negotiate a treaty that would allow Boers peacefully to settle land adjoining the Zulu kingdom. Dingaan said he would let the Boers live in Natal if they recovered cattle stolen by a Tlokwa chieftain. Retief and his men did so, and Dingaan agreed to give the land to the Boers.

Retief returned to Umgungundhlovo on February 3, 1838, to finalize the agreement. He arrived with 60 volunteers, including his own son and three children of other men — it was common for children to accompany their fathers on expeditions of this kind. The next day, Retief and Dingaan formally signed a treaty — the Zulu king made his mark by scratching an “X” on the document — giving possession of the land to the Boers. Delighted, the Boers sent scouts back to the main encampments to report the successful outcome and made ready to leave. As Retief and his party were about to saddle up, a messenger arrived from Dingaan inviting the Boer party to a special celebration to mark the signing. Retief was suspicious but did not want to offend Dingaan. As they had on previous visits, the Boers stacked their firearms neatly outside the reed walls and entered the royal enclosure unarmed.

As they ate and drank, a Zulu impi, or warrior unit, put on a dance for the guests. According to the account of a white missionary who was present, the dancing warriors drew ever closer to the Boers, till they were just in front of the seated whites. When the Zulu king leaped to his feet and shouted, “Kill the white wizards!” the impi fell upon the surprised Boers. Some of them drew their hunting knives and tried to fight off the attackers, but they were quickly overwhelmed.

The Zulu warriors bound the whites with reed ropes and dragged them to Hlomo Amabutho, the Hill of Execution, near the Zulu capital. There they clubbed the Boers to death, one by one, with Retief kept until last and forced to watch his son being murdered. After Retief’s heart was extracted and presented to Dingaan as proof that the Boer leader was dead, the bodies were left for the vultures, in accordance with Zulu custom.

Dingaan then gave orders for the full might of his army to attack the Boer camps. The settlers had received the message Retief had sent earlier and believed everything had gone well. They were therefore completely unprepared and badly undermanned. The 60 men in Retief’s party were all dead. Many other men had gone hunting, leaving only a light guard for the women and children. The Boers were so confident there would be peace that they had not even posted sentries. Just before dawn, barking dogs aroused the outlying wagons. Then, thousands of Zulu warriors attacked the several hundred trekkers — women, children, and old men — as they lay sleeping.

The Boer historian, Gustav Preller, who interviewed survivors, left a harrowing account of the aftermath: “All around dozens and dozens of bodies . . . babies who had had their heads smashed open against the wagon wheels, women, dishonored and in some Zulu custom, their breasts cut off . . . [I]n a wagon, blood filled to a height of several inches, the life blood of an entire family ebbed out where they lay . . . Jan Bezuidenhout, one of the few young men who had not gone ahead with the Retief party, grabbed his four-month-old baby daughter out of her crib and ran off through the undergrowth . . . [H]aving lost his pursuers a few miles away, Bezuidenhout checked for the first time on his daughter in his arms. She was dead; a single spear stroke had killed her.”

The slaughter became known as the Weenen, the Dutch word for weeping, and a town of that name still stands near the site. Of the 600 Boers camped in the area, Zulus killed some 300, including 185 children. The rest survived because grazing requirements for their animals meant that the Boer camps had to be widely dispersed. If Dingaan’s men had scouted more thoroughly, found all the encampments, and attacked them simultaneously, the slaughter would have been far greater.

Pretorius arrives

The Boers now faced their greatest challenge. Their camps were full of wounded men, orphaned children, and widows. The Zulus had stolen an estimated 25,000 head of cattle and sheep during the Weenen slaughter, and ammunition was running low. The Zulu armies might return at any time, and they were a formidable force, as the Boers discovered when they launched a raid to avenge the massacre. On April 6, 1838, 347 trekkers under a divided command of Piet Uys and Hendrik Potgieter rode into Zulu territory only to be defeated by some 7,000 warriors not far from Umgungundhlovo in what became known as the Battle of Italeni.

This new disaster forced the Boers to face reality: They had to either abandon their quest for independence and return to the Cape Colony, or find some means to fight their way through. The widows and orphans argued strongly for pushing on. They knew that if they fell back to the Cape they would have to live on charity, whereas if Dingaan could be defeated they could at least recover their livestock. Many Boers were also convinced that God favored them, and that setbacks were only a test of faith.

It was at this moment of indecision that a popular lawyer named Andries Pretorius answered the trekker call for reinforcements, and rode into camp with 60 men and a brass cannon. The Boers appointed him commander in chief on November 25, and he immediately began preparing a strike against the Zulu.

His means were few. A force of only about 468 Boers, including three Scotsmen, set out on November 27 seeking battle. For extra protection, the Boer column of 64 wagons traveled four abreast, instead of the usual single file. Each night, they formed a circular defensive formation, known as a laager.

Pretorius realized that even with two front-loading cannon, his force was too weak to defeat the Zulu army in an open field. He therefore decided to draw the enemy into an attack on the Boer encampment. Each day patrols and scouting parties rode ahead, sometimes led by Pretorius himself, to make sure no unexpected surprises were waiting over the horizon.

On December 9, 1838, the Boer party reached the Zandspruit tributary of the Waschbank River. It was here that the Boer chaplain, Sarel Cilliers, first pledged during his nightly sermon that if God helped them defeat the Zulus, they and their descendents would celebrate that day in honor of God, and that they would build a church in commemoration. The Boers repeated this oath, known in Afrikaner folklore as “the covenant,” every night until they met the enemy.

There appeared to be no movement from the Zulu side. On December 12, Pretorius decided to move camp to the Buffalo River, hoping to provoke the Zulus by moving farther into their territory. That day, he sent out two patrols, one under the command of his deputy, Commandant Hans De Lange, and another, under the Scotsman Edward Parker. This latter group saw action when they came upon a small group of Zulus. They killed the warriors and took the women prisoner.

Pretorius drew up a message for Dingaan on a white cloth, explaining that he was leading a commando to punish the Zulus. If, however, Dingaan was willing to cooperate, Pretorius wrote, he was still willing to make peace — a generous offer in light of the earlier betrayal. He freed the prisoners and told them to give the message to Dingaan. He received no answer.

On December 13, the Boers spotted Zulus and what appeared to be a large number of cattle near their camp. Piet Uys had been tricked by such a ploy at the Battle of Italeni. Zulu warriors, crouching behind toughened animal-skin shields, looked like cattle from a distance, and Uys dropped his guard. He was killed in a surprise attack by the “cattle.”

Pretorius did not make the same mistake, and he sent a 120-strong mounted unit to investigate the “cattle.” They turned out to be Zulus, and in the short fight that followed the Boers killed eight warriors but suffered no casualties. Pretorius now suspected that the Zulus were preparing for battle.

On December 15 he moved the Boer camp to a position alongside the Ncome River, itself a tributary of the Buffalo River. A scouting expedition that day confirmed the presence of two huge Zulu armies a short distance away.

Pretorius prepared for battle. His men drew the wagons into a D-shaped formation, one side overlooking a large hippopotamus path facing the Ncome River, another side facing a soil erosion ditch, and the third side facing the open plain. Pretorius chose the site to limit the directions from which the Zulus could attack.

The laager was large enough to contain all the horses and oxen. The defenders tied the wagons together with leather ropes, and closed off all openings between and below the wagons with a Pretorius innovation, so-called fighting gates, which were slatted wood fixtures through which defenders could fire. They left two small openings, sealed with removable fighting gates, so cavalry could leave the laager. Finally, they attached lanterns to the ends of large ox-whips planted upright in the ground. These dangled in front of the laager and were to serve as forward lighting during the dark hours when Zulu usually attacked. Zulus captured after the battle said they had believed the lights waving in the breeze above the Boer camp were spirits, and that fear of the spirits kept them from attacking that night.

Battle is joined

In Pretorius’s own account of the battle, he wrote that as the mist cleared on the morning of December 16, he saw that the Boer camp was completely encircled by tens of thousands of Zulu warriors, even where the terrain would have made an attack difficult. Estimates placed the number of Zulus at between 15,000 and 25,000, although no official count was possible. Whatever the figure, Pretorius wrote that it was a “terrible sight.”

The Boers had been ready and armed since two hours before daybreak. The two cannon were in position, and the fighting gates closed. The defenders expected to run out of ammunition for the cannon, and had stacked up suitably sized stones at strategic points along the perimeter to fire as a last resort. The Boers would fire stones that day.

The front lines of the Zulu force were still, squatting, only about 40 paces from the wagons, waiting for the signal to attack. Pretorius decided to strike first. At his signal, three bursts of fire from the Boer guns and two blasts from the cannon broke the silence. The Boers’ orders were to then hold their fire. As the billows of gunpowder smoke lifted, they saw that the surviving Zulus had fled some 500 paces from their former front line, leaving behind dozens of dying and dead comrades.

The Boers then heard the noise of the Zulus breaking their spear shafts to make them into short, stabbing weapons. A frontal assault was coming. A few minutes later, the Zulu force stormed the wagons, screaming wildly, shields held high, and assegais in readiness. Withering gunfire ripped through the Zulu ranks, and while some managed to reach the wagons, they were gunned down before they could cut through the wagon canvasses.

Another group of Zulus tried to attack from inside the erosion ditch by standing on each others’ shoulders and scrambling over the edge. Pretorius ordered Cilliers, the fighting churchman, to see off the attack. He led a group of men out of the relative safety of the wagon perimeter, and they proceeded to kill some 400 Zulus. One Boer, Philip Fourie, was wounded when an assegai struck him in the side.

The Boers then wheeled one of their cannon out of the laager, pointed it into the ditch, and fired a shot that literally blew apart the assaulting party. The survivors fled the ditch in disarray. This sparked a temporary retreat by the Zulu, and marked the end of the second unsuccessful attempt to break the Boer lines. The wounded Boer, Fourie, returned to the wagon circle for treatment.

As the Zulus waited for new orders, Pretorius ordered another burst of cannon fire into their ranks, provoking a spontaneous charge against the wagons. Although it was the longest single assault of the nine-hour battle, it was utterly defeated, as the Boers cut down wave after wave of attackers. Gun barrels got so hot men had to hold them with wet cloths for reloading.

As the third attack fell back, the Boers launched their first surprise counterattack, as the mobile fighting gates swung open and a cavalry unit charged the Zulu lines. Shooting from the saddle, the Boers tried to turn the Zulu lines to their left. Desperate Zulu resistance, which saw hundreds more of their number killed, stopped the encircling action, and the Boer horsemen rode back to the wagons. They regrouped and launched a second attempt, driving the Zulus further away. A third mounted charge finally broke through the Zulu lines. The Boer cavalry then turned and attacked the Zulus from the rear. Pinned between the cavalry and cannon fire from within the wagon circle, the main Zulu force facing the open plain scattered.

A reserve Zulu force tried to cross the Ncome River to attack the laager but so many warriors were gunned down that their blood stained the water red. Pretorius himself then led another cavalry charge from within the laager. Cut to pieces, with thousands dead, the Zulu army, which had courageously charged repeatedly against a better-armed enemy, finally broke ranks and fled.

Pretorius divided his cavalry into two units and sent them in pursuit. Mounted Boers killed hundreds of warriors during a three-hour chase. It was during this pursuit that Pretorius was wounded. Two other Boers, including Fourie, suffered nonfatal assegai wounds, but these were the only Boer casualties. An estimated 3,000 Zulus died on the battlefield, and many more died later from wounds.

The Aftermath

Early the next morning, Pretorius ordered the camp broken, and marched the commando straight to the Zulu king’s capital. He was confident the Zulus no longer posed any significant threat, but he hardly expected the sight that awaited him on December 20 at Umgungundhlovo. Dingaan had fled with his wives and cattle, leaving the circular camp of reed huts burning, as a symbol of the destruction of Zulu power.

On the outskirts of the capital the Boers found the skeletons of Retief and his men. “Their hands and feet were still bound fast with thongs of ox hide,” wrote Cilliers, “and in nearly all the corpses a spike as thick as an arm had been forced into the anus so that the point of the spike was in the chest.” Retief, who was identified by the remains of a satin vest he had worn, still had a leather bag draped over his shoulder bone. In it was the treaty, signed by Dingaan, giving the Boers the unoccupied land to the north. According to one of the Boers who saw it, the treaty was astonishingly well preserved — as if it had been “left in a closed box.” Pretorius’s men buried Retief and his party on Christmas Day 1838.

Dingaan fled north but was captured by a rival tribe, the Swazis. Earlier, he had persecuted the Swazis, and they murdered him in revenge. The new Zulu king, Mpande, was officially installed in 1840, and confirmed the contents of the treaty with the Boers, who established their first republic in southern Africa. Also in 1840, in fulfillment of their covenant, the Boers built a church to mark the Blood River victory.

The Battle of Blood River entered the Afrikaner psyche as a divinely-inspired victory, and December 16 became a public holiday in South Africa, celebrated each year with festivals, church services, and reenactments. The battle represented the victory of European civilization over the darkness of Africa, of Christianity over heathens. It helped justify white supremacy and the self-appointed right of Afrikaners to rule over, not apart from, the black tribes.

Yet the Battle of Blood River, in many ways, symbolized all that was wrong with the white settlement of southern Africa, and why that experiment failed. The Boers are to be praised for wanting to settle unoccupied land peacefully, and for seeking the friendship of neighboring peoples, but neither they nor their descendents understood that demography is the arbiter of nations. Those who form the majority population of a territory will rule that territory, no matter how powerful a ruling elite may be. They will determine its culture and society. A majority-European population will create a society that reflects European values and norms. A majority-African population will create a society that reflects African norms.

The Boers never understood this. Even at the Battle of Blood River they had at least 60 black servants and an indeterminate number of mixed-race servants, who helped load weapons. Parker, one of the Scotsman, had more than 100 black servants.

To the present day, the overwhelming majority of Afrikaners have black servants who work on farms, in factories, and in homes. Afrikaners failed to understand that by giving the native population the benefits of European civilization, blacks would grow in numbers and overwhelm their society. The Cape Colony and the original Boer republics, which were largely uninhabited by natives when they were settled by Europeans, are today home to tens of millions of Africans.

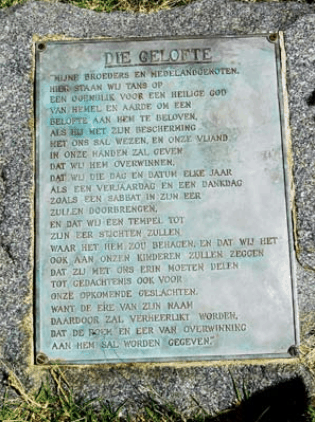

The Blood River vow.

The Church of the Vow, built by the Boers in 1840, still stands in the town of Pietermaritzburg, named after Piet Retief. But Pietermaritzburg, supposedly the symbol of the Boer victory over the Zulus, is today part of a municipality called Umgungundhlovo, named after Dingaan’s capital. It is also the capital of the South African province of Kwa-Zulu Natal, and its population is more than 95 percent black.

The Church of the Vow stands alone, graffiti-scarred and abandoned, in a dirty downtown slum. Its decay illustrates the fatal error made by the victors of the Battle of Blood River, that of ignoring the demographics of race. If whites had taken possession of those unoccupied lands and kept them for themselves alone the history of South Africa would have been entirely different.

If the Boers had inhabited and worked their own land rather than rely on black labor, the states they created might still be strong and independent today. Their decision to use non-white labor was a critical error that undid all of the sacrifices of the early pioneers.

The only way to maintain a civilization is for the majority to occupy its own land with its own people, and to do its own manual labor. This law governs the rise and fall of civilizations, and the victors of Blood River ignored it, to their cost.