The War on White Heritage

Sam Francis, American Renaissance, July 2000

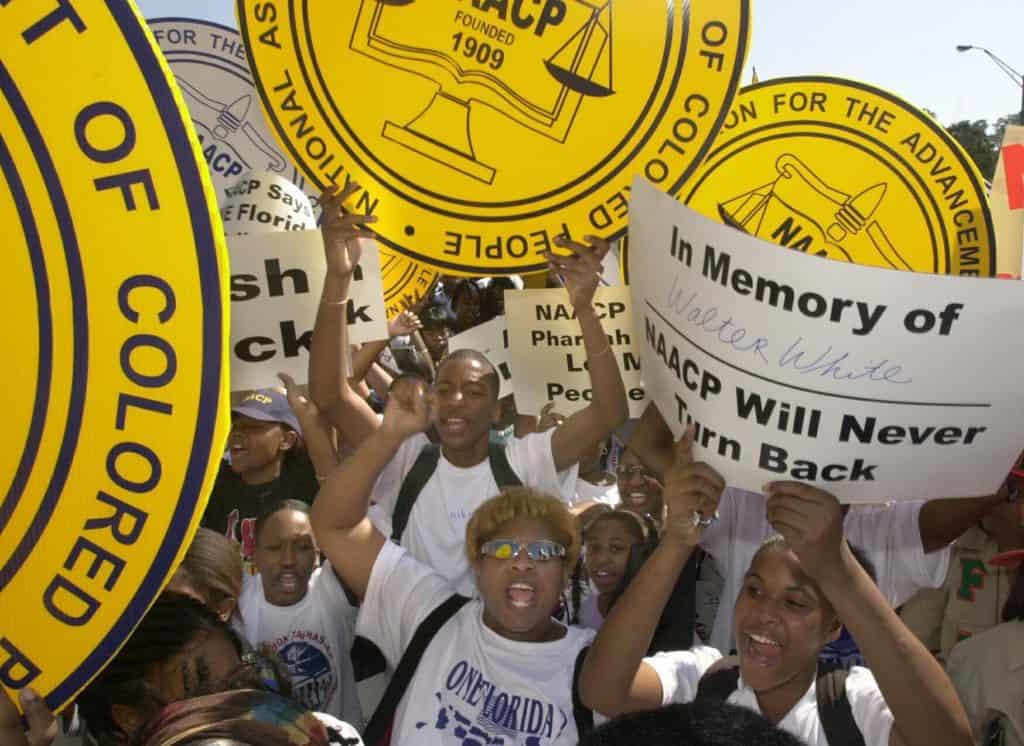

After years of bitter controversy, the South Carolina legislature voted in May to take down the Confederate battle flag that has flown over the state capitol in Columbia since 1962 and to move it to “a place of honor” at the Confederate Soldiers Memorial located on the capitol grounds. The legislature’s vote on the flag is regarded as a defeat for the defenders of the flag, mainly a coalition of Southern traditionalist groups and Civil War buffs, and a victory for the opposing coalition that demanded the removal of the flag: the NAACP, Big Business, and an odd partnership of political liberals and conservatives.

Many white Americans, especially those outside the South, have shown little interest in the controversy and wonder why it even exists. They regard the issue as one of exclusively Southern, historical, or black interest and fail to see the larger implications of the controversy for themselves. The fact is, however, that the conflict over Confederate symbols is not only about those symbols or even about honoring the Confederacy, but also about issues of national and racial heritage with which all white Americans should be concerned regardless of what they think of the Civil War or where they live.

Southern traditionalists and Civil War buffs honor the Confederate flag and similar symbols for a variety of reasons, but those symbols are as much a part of general American history as the “Don’t Tread On Me” rattlesnake flag of the American Revolution or the Lone Star flag of the Republic of Texas. Until recently, few Americans saw any difference between honoring and displaying those historic banners of American legend and honoring and displaying the Confederate battle flag or the several other flags associated with the Confederacy.

Only with the advent of the “civil rights” era and of mandated racial equality have the Confederate flag and all other symbols associated with the Confederacy been singled out for attack, and of course the reason is that these flags and symbols are the emblems of a government and culture that was based on slavery and racial inequality. In an age in which the egalitarian imperative is absolute and “racism” is virtually a religious taboo, continuing to honor and display these symbols in public — especially by state and local governments — constitutes an outright act of resistance to the dominant egalitarian orthodoxies.

Moreover, the NAACP, which has been crusading against Confederate symbols for decades, is increasingly tipping its true hand, revealing that behind its overblown rhetoric about the flag (a 1991 NAACP resolution characterized the Confederate flag as “an odious blight upon the universe” and “the ugly symbol of idiotic white supremacy racism and denigration” [sic]) and the Confederacy lies another, far broader, and much more radical agenda. The NAACP and similar groups want the removal and erasure not only of Confederate symbolism but also of a wide range of symbols and icons from American history that have no association with the Confederacy or the ante-bellum South. The purpose of this attack is to emphasize that American civilization itself is “racist” and that virtually all the symbols, icons, heroes, songs, and institutions of the American past or at least its most important and defining ones have to be discarded or radically reconstructed to suit the new “anti-racist” dogmas the NAACP upholds.

Credit Image: © Orlando Sentinel / TNS / ZUMAPRESS.com

In launching this broad attack on the historic symbolism of America, the NAACP is embarking on what is almost explicitly a revolutionary course, intended eventually to lead to the destruction of the traditional civilization of the United States and the establishment of a new, purportedly egalitarian, and essentially totalitarian order that replaces the real, historic traditions of the American past with the fabricated propaganda and “Afrocentric” racial mythology of which the NAACP approves.

In this new order, whites — whether Southern or not — would be denied any public affirmation of their cultural and historical identity, and the denial of their identity would more easily allow their cultural and political subjugation to the non-white majority that has been projected to emerge in the United States in the next half century. The end result of the attack on Confederate symbolism, in other words, is not merely the disappearance of the Confederate flag, “Dixie,” and other symbols and customs of interest mainly to Southerners and Civil War buffs but, in time, the eradication of all symbols from pre-1960s America that suggest a white-based or “Eurocentric” public identity. With their disappearance and the cultural and racial dispossession it represents would come the racial domination of white Americans by the non-white majority of the next century.

The crusade against Confederate symbolism is so far the most developed part of the anti-white attack on American civilization, and the NAACP and other black nationalist groups have emphasized such symbols because, given their historical association with slavery, they can more easily build a case against them and attract the support of white allies. Given the power of egalitarian propaganda, few mainstream leaders, either conservative or liberal, are willing to defend Confederate symbolism, and some of the most effective enemies of the flag have been Republicans, “conservatives,” or white Southerners themselves.

In the 1990s, the war on public Confederate symbolism escalated dramatically, with the NAACP demanding the removal of Confederate flags flown over state capitols in Alabama as well as South Carolina. In the former state, the governor removed the flag after a state judge ruled in 1993 that flying it violated state law. Also in 1993, the white liberal Democratic governor of Georgia, Zell Miller, sought to alter the design of his state’s official flag, which contains a Confederate battle flag, on the grounds that it would be an “embarrassment” to the state during the Olympic Games scheduled for 1996. The governor’s efforts were unsuccessful. In Mississippi, there are current demands to remove the Confederate battle flag in the corner of the state flag, and the governor has appointed a commission to consider doing so. There are also controversies about the state flags of Arkansas and Florida, which contain designs either symbolizing the Confederacy or resembling its flag.

In addition to attacks on the flag, songs such as Virginia’s state anthem “Carry Me Back to Ole Virginny” and Maryland’s “Maryland, My Maryland” have also been attacked as “racist.” At the University of Mississippi, the Confederate flag and similar symbols, including the football team mascot, “Colonel Reb,” a caricature of a Confederate officer, have been banned by the university administration.

The Gen. Robert E. Lee in Richmond, Virginia. (Credit Image: © Chuck Myers / MCT / ZUMAPRESS.com)

Virginia, and especially the state (and Confederate) capital of Richmond, has been the scene of some of the most bitter and far-reaching attacks on Confederate symbolism. The construction of a statue of black tennis player Arthur Ashe in 1995-96 on Richmond’s Monument Avenue — famous for statues honoring Confederate leaders — was intended to disrupt the symbolism of the monuments. In 1999, another controversy erupted in Richmond over a mural that displayed a picture of Robert E. Lee. Black city councilman Sa’ad El-Amin demanded that it be removed and threatened violence if it were not. “Either it comes down or we jam,” he said. The Lee portrait was later firebombed and defaced with anti-white invectives and racial epithets (“white devil, black baby killer, kill the white demons”). Earlier this year Mr. El-Amin and other blacks on the city council voted to remove the names of Confederate generals from two bridges in the city and rename them after local “civil rights” leaders. El-Amin also announced that “Monument Avenue is on my list of targets.”

The NAACP also embarked on a campaign to force the Virginia governor to cancel annual proclamations of April as “Confederate History Month” and threatened a boycott of the state if the custom were continued. “Anything less” than promising not to issue the proclamation again “is unacceptable,” Salim Khalfani, state director of the NAACP, proclaimed. On May 10, Republican Governor James Gilmore reached a “compromise” that consisted of a promise to “reconsider” Confederate History Month and to meet regularly with NAACP leaders if they did not proceed with plans for a boycott. It is probable that proclamations of “Confederate History Month” will be discontinued.

It has been in South Carolina, however, that the most protracted controversies over the Confederate flag have taken place. The state legislature in 1961 enacted a public law mandating that the Confederate battle flag be flown over the state capitol dome beneath the American flag and the state flag. Contrary to what the flag’s enemies have asserted, this was not so much defiance of the “civil rights” movement as the desire, encouraged by the U.S. Congress and President Eisenhower, to mark the centennial of the Civil War. The flag at that time was largely uncontroversial, and it remained so until the early 1990s.

In 1994, the NAACP announced it would boycott the state unless the flag were removed, but a populist campaign under the leadership of the Council of Conservative Citizens (CofCC) was able to prevent the flag’s removal, and in the gubernatorial campaign of that year, the Republican candidate David Beasley promised he would not seek to take down the flag. Soon after being elected, however, Gov. Beasley embarked on a campaign to do just that. Flag supporters and the CofCC went on to lead a movement to unseat the governor for his betrayal. Gov. Beasley was defeated in his re-election campaign in 1998; he has since acknowledged that his reversal of position on the flag was the main reason for his defeat.

In 1999 the NAACP returned to the fight, announcing yet another boycott. This time the boycott attracted the support of liberal organs like the New York Times and Washington Post. The Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the National Urban League, the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and the National Progressive Baptist Convention all canceled conventions in South Carolina. The state Chamber of Commerce told Republican lawmakers that “businesses were considering cutting off campaign contributions to lawmakers who support the flag,” and major foreign corporations that have built plants in the state — BMW and Michelin Tire — also demanded that the issue be “resolved quickly” (meaning that the legislators accede to black demands).

Flag defenders were by no means idle during the controversy, and in October, 1999, and January 2000, they staged mass demonstrations in Columbia. Nevertheless, the charges of “racism” lobbed at anyone who defended the flag, threats to the $14.5 billion-a-year tourism industry, and the general desire for acceptance by the cultural mainstream all led to a “compromise” measure that relocated the flag to the Confederate Soldiers Memorial. As Julian Bond, national president of the NAACP, remarked, “Money talks.”

Credit Image: © Erik S. Lesser / ZUMAPRESS.com

But the removal of the flag in South Carolina can be expected only to unleash an even more frenetic crusade against Confederate symbols. As Dr. Neill Payne, executive director of the Southern Legal Resource Center, remarked just afterwards, the vote simply means that it is now “open season on all things Confederate.” Flag enemy Georgia state Rep. Tyrone Brooks explained, “It’s like the civil rights movement. Once we win in South Carolina, we move to Georgia. Once we win in Georgia, it’s on to Mississippi.” The vote in South Carolina only encourages the NAACP and its allies and creates further problems for the mainstream conservatives and businessmen whose principal concern is to avoid controversy.

Indeed, while the main reason for the retreat in South Carolina was fear of the boycott, the NAACP not only refused to call off the boycott after the vote but threatened to intensify it unless the flag were removed from the capitol grounds entirely. NAACP national executive director Kweisi Mfume complained that “to take it from the top of the dome where you had to strain to see it, and move it to a place where anyone coming down the main street will see it is an insult.” Even as the House voted to adopt the compromise measure, black demonstrators burned Confederate and Nazi flags at the Confederate Soldiers Memorial and then sprayed anti-white invectives on the monument itself.

The premise of the compromise was an acknowledgment that while the Confederacy is an important and legitimate part of the South Carolina heritage, it is not (as flying the Confederate flag over the capitol might be taken to imply) the whole or the dominant part of it. Yet the NAACP’s demand that any honoring of the flag be abolished refuses to concede that the Confederacy has any legitimate place in South Carolina or American history at all. The rejection of the Southern and American past was implicit in signs carried by black anti-flag demonstrators last winter that read, “Your Heritage Is Our Slavery.” In rejecting the heritage of the South as merely one of their own enslavement and exploitation, blacks are in effect affirming that they are not part of the culture and nation that are the present-day product of that heritage. What they presumably want celebrated and honored is not the real heritage of the South, in which blacks played a major if subordinate role and from which blacks have derived much of their own cultural identity, but the total extirpation of those parts of the Southern past they find “offensive” (i.e., anything that does not glorify blacks) and the rewriting of the past to magnify and glorify the achievements of their own race.

The black demand for the total extirpation or rewriting of the past is not confined to the South and the Confederacy, however, but also extends to symbols associated with other ethnic groups. Earlier this year the Boston Housing Authority asked residents of public housing to remove displays of shamrocks — which it likened to swastikas or Confederate flags — because this symbol traditionally associated with the Irish was “unwelcome” now that black residents vastly outnumber those of Irish heritage.

But the non-white demand for the erasure of white ethnic and cultural symbols also includes the major symbols of the entire American nation and its past. Indeed, Randall Robinson, a black activist who played an important role in lobbying for sanctions against South Africa to end apartheid, writes that America “must dramatically reconfigure its symbolized picture of itself, to itself. Its national parks, museums, monuments, statues, artworks must be recast in a way to include . . . African-Americans.” It does not seem to matter to Mr. Robinson that the historical events many of these cultural monuments commemorate might not have included blacks; the past must be recreated to include them.

Black rejection of not only the Confederate but the American heritage is clear in the removal of the name of George Washington from a public school in New Orleans. On Oct. 27, 1997 the Orleans Parish School Board, with a 5-2 black majority, voted to change the name of George Washington Elementary to Dr. Charles Richard Drew Elementary (Drew was a black surgeon who made advances in preserving blood plasma); the school itself is 91 percent black. “Why should African-Americans want their kids to pay respect or pay homage to someone who enslaved their ancestors?” asked New Orleans “civil rights” leader Carl Galmon. “To African-Americans, George Washington has about as much meaning as David Duke.”

The same school board also has stripped the names of Confederate Generals P.G.T. Beauregard and Robert E. Lee from schools, under a policy adopted in 1992 that prohibits naming schools after “former slave owners or others who did not respect equal opportunity for all.” Southern slave owners and Confederate generals are, of course, mainly of Southern and local interest, but George Washington is probably the most significant national symbol in the American pantheon. The New Orleans school board decision, the New York Times commented at the time, “underscores the maxim that history is written by those with the power.” In this case, those who have the power are blacks who insist on celebrating their own race and discarding the national heroes of whites.

But Washington is by no means the only American icon to be rejected for his “racism.” In 1996, white former Marxist historian Conor Cruise O’Brien published an article in The Atlantic Monthly arguing that Thomas Jefferson should no longer be included in the national pantheon because of his “racism.” Again, Jefferson, second only to Washington perhaps, is one of the major heroes of the national saga. Rejecting Washington and Jefferson as well as the Confederacy and all slave owners (including many who signed the Declaration and the Constitution and all but two of the first seven presidents of the United States) by itself would effectively alter American history and the American national identity so radically as to be unrecognizable. That is precisely what the Afro-racists plan to do.

Danger: white supremacists.

The editor of Ebony magazine Lerone Bennett, Jr. is the author of a recent book denouncing Abraham Lincoln for his “racism.” As described in Time magazine (May 15), Mr. Bennett says “Lincoln was a crude bigot who habitually used the N word and had an unquenchable thirst for blackface-minstrel shows and demeaning ‘darky’ jokes,” and he also discusses Lincoln’s remarks about blacks in the debates with Stephen Douglas and on other occasions, as well as his plan to remove blacks from the United States to colonies in Central America. While Bennett’s facts about Lincoln are substantially correct, his book is intended as an attack on and debunking of a major president regarded by many Americans as an iconic figure especially associated with the abolition of slavery and the triumph of egalitarianism.

In February, the New Jersey Senate debated a bill that would have required students in public schools to memorize part of the Declaration, but the bill’s sponsor withdrew it after angry attacks by black lawmakers. As the Associated Press reported, “They objected to the clause that says, ‘All men are created equal’ because when the Declaration was written, that basic democratic principle did not apply to black people.” As black state Sen. Wayne Bryant said, “It is clear that African Americans were not included in that phrase. It’s another way of being exclusionary and insensitive . . . You have nerve to ask my grandchildren to recite [the Declaration]. How dare you? You are now on notice that this is offensive to my community.” He claimed that the bill would involve “reliving slavery.”

The assault on the historic American identity is not mounted only by blacks. Indians and Hispanics in the western part of the United States engage in much the same erasure of white, European symbols and the construction of symbols that glamorize their own cultures. In 1994, the city of San Jose, California, rejected a proposal to construct a public statue of Col. Thomas Fallon, the American soldier who captured the city for the United States in the Mexican-American War, and voted instead to build a statue of the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl.

In San Francisco in 1996, American Indians denounced the relocation to a place outside city hall of a statue honoring the Catholic missionaries who founded the city. The statue shows a reclining Indian with a Franciscan monk standing over him. The American Indian Movement Confederation opposed its relocation, saying that the statue “symbolizes the humiliation, degradation, genocide and sorrow inflicted upon this country’s indigenous people by a foreign invader, through religious persecution and ethnic prejudice.” As in South Carolina, whites compromised — by adding a plaque that read, “With their efforts over in 1834, the missionaries left behind about 56,000 converts — and 150,000 dead. Half the original Native American population had perished during this time from disease, armed attacks and mistreatment.” The statue, designed to commemorate the missionaries’ compassion for the Indians, had been transformed into a confession of genocide. At the demand of the Catholic Church, however, the words “and 150,000 dead” were omitted.

The black and other non-white attacks on historic symbols and icons, therefore, are by no means confined to those associated with the Confederacy but extend to symbols associated with anything non-whites find “offensive.” Given the standards by which the NAACP and similar racial extremists select their targets, there is no reason they should not demand the abolition of the American flag and the U.S. Constitution itself. The Constitution indirectly refers and gives protection to slavery several times, and the American flag flew over a nation in which slavery was a legal and important part of the economy and society far longer than the Confederate flag flew over the four-year Confederacy.

Indeed, the factual premises of the NAACP — that American history is inseparable from recognition of racial inequality and racial differences — are generally correct. As I wrote in American Renaissance in January 1999, throughout American history, “We — Americans in general and our public leaders in particular — repeatedly and continuously recognized the reality and importance of race and the propriety of the white race occupying the ‘superior position,’ and indeed it is difficult to think of any other white-majority nation in history in which recognition of the reality of race has been so deeply imbedded in its thinking and institutions as in the United States.” Given that history, there is virtually no figure, event, or institution of the American past that would not be “offensive” to non-whites today and the obliteration of which they could not as logically demand as they do that of Confederate symbols.

I also wrote, “You cannot have it both ways: either we define the American nation as the product of its past and learn to live with the reality of race and the reality of the racial particularism and racial nationalism that in part defines our national history, or you reject race as meaningful and important, as anything more than skin color and gross morphology, and demand that anyone, past or present, who believes or believed that race means anything more than that be demonized and excluded from any positive status in our history or the formation of our identity. If you reject race, then you reject America as it has really existed throughout its history, and whatever you mean by ‘America’ has to come from something other than its real past.”

It is, of course, the latter course, of rejecting the real past of the United States, that the NAACP and other non-white racial extremists have taken, and that rejection is what makes them extremists. It does not seem to occur to them that there are other “heritages” in the United States besides their own or other communities to which such symbols as Washington and Jefferson, the Declaration and the Confederacy, mean something other than the enslavement and exploitation of blacks.

The indifference and hostility of non-whites to symbols and icons of white heritage and identity expose the central fallacy of the “multiracialism” that our current political and cultural elites promote. Its premise is that different races and ethnic groups can all “get along” with each other, that they can live together in egalitarian harmony, and that, as President Clinton said in 1998, “we can strengthen the bonds of our national community as we grow more racially and ethnically diverse.”

But the reality is that the egalitarianism and universalism of the “civil rights” era have led to the rediscovery of race and the rebirth of racial consciousness among non-whites and hence to the animosity that non-whites feel toward whites and their heritage. It is racial consciousness, not egalitarianism and universalism, that fuels the non-white crusade against the American past, and obviously, if “multiracialism” means that some races with more consciousness, more solidarity, and more power can boycott and bludgeon out of existence the symbols of other races and the cultural legacies the symbols represent, then multiracialism promises nothing but either perpetual racial conflict or merely the same kind of racial supremacy that used to exist in the United States — though with a different supreme race whose rule would be perhaps considerably more draconian than that of whites. Of course, whites can always try to buy temporary peace and harmony by agreeing to every demand of non-white radicalism and abandoning the symbols of their own heritage. That, of course, is exactly what whites today are doing, though every concession merely leads to further demands from non-whites.

It may be that the coalition of Southern traditionalists and Civil War buffs who have been the main defenders of the Confederate flag has committed a tactical error by trying to define the flag as purely a Southern symbol. By doing so, they may have encouraged white Americans outside the South and white Southerners who are indifferent to the Confederacy to believe that the controversy does not have implications for them. Indeed, some of the more zealous attacks on “Yankees” by Southern traditionalists may only have alienated non-Southern whites, and by dwelling on the “Southern-ness” of the flag and its meaning in the Civil War, its defenders may have unnecessarily alienated potential allies.

What the racial assault on the Confederacy and other non-Confederate symbols really shows, however, is not only the dangerous flaws of multiracialism and the inexorable logic of the racial revolution of this century but also that today regional differences among whites — like many other cultural and political differences — are no longer very relevant. It shows that Southerners and “Yankees” today face common enemies and common threats to their rights, interests, identity, and heritage as whites, and that the forces that have declared war on them and their heritage define themselves as well as their foes not in political, regional, or cultural terms but in terms of race. Whites who have been indifferent to the fate of the Confederate flag and similar symbols in the recent controversies should not be surprised, therefore, when historical symbols important to their own identity come under assault from anti-white radicals in the future.

And it is as a race that whites must now learn to resist the war being waged on them. So far from being a symbol of a lost and forgotten cause relevant only to a dwindling band of Confederate loyalists, the Confederate flag and the battles swirling around it today should serve as reminders to all white men and women of a simple lesson: Unless they forsake the many obsolete quarrels and controversies that have long divided them and learn to stand, work, and fight together for their own survival as a people and a civilization, the war against them that their self-proclaimed racial enemies are waging will not permit them or their legacy as a people and civilization to survive at all.