Push to End Prison Rapes Loses Earlier Momentum

Deborah Sontag, New York Times, May 12, 2015

The inmate, dressed in prison whites with a shaved head and incongruously tender eyes behind wire-rimmed glasses, entered the visiting room with her wrists joined as if she were handcuffed. At 31, she had spent her whole adult life behind bars, and it looked like a posture of habit.

She introduced herself: “My given name at birth was Joshua Zollicoffer, but my preferred name is Passion Star.”

A transgender woman whose gender identity has been challenged by Texas authorities, Ms. Star herself is challenging Texas’ refusal to accept new national standards intended to eliminate rape in prison, which disproportionately affects gay and transgender prisoners. Last spring, Gov. Rick Perry declared in a letter to Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr. that Texas had its own “safe prisons program” and did not need the “unnecessarily cumbersome and costly” intrusion of another federal mandate.

Ms. Star, who says she is a victim of repeated sexual harassment, coercion, abuse and assault in Texas’s maximum-security prisons for men, disagrees.

“Look, I got 36 stitches and have scars on my face that prove the prisons are not safe and the current system does not work,” she said. “Somebody needs to be intrusive into this state’s business. Because if somebody was intruding, probably these things would not happen.”

After decades of societal indifference to prison rape, Congress, in a rare show of support for inmates’ rights, unanimously passed the Prison Rape Elimination Act in 2003, and Mr. Perry’s predecessor as governor, President George W. Bush, signed it into law.

“The emerging consensus was that ‘Don’t drop the soap’ jokes were no longer funny, and that rape is not a penalty we assign in sentencing,” said Jael Humphrey, a lawyer with Lambda Legal, a national group that represents Ms. Star in a federal lawsuit alleging that Texas officials failed to protect her from sexual victimization despite her persistent, well-documented pleas for help.

But over 12 years, even as reported sexual victimization in prisons remained high, the urgency behind that consensus dissipated. It took almost a decade for the Justice Department to issue the final standards on how to prevent, detect and respond to sexual abuse in custody. And it took a couple of years more before governors were required to report to Washington, which revealed that only New Jersey and New Hampshire were ready to certify full compliance.

With May 15 marking the second annual reporting deadline, advocates for inmates and half of the members of the National Prison Rape Elimination Commission, a bipartisan group charged with drafting the standards, say the plodding pace of change has disheartened them despite pockets of progress.

{snip}

Some commissioners fault the Justice Department for failing to promote the standards vigorously. Others blame the correctional industry and unions for resisting practices long known to curb “state-sanctioned abuse,” as one put it. All lament that Congress has sought to weaken the modest penalties for noncompliance, and that five governors joined Mr. Perry last year in snubbing the standards.

{snip}

Last year, 42 governors signed a form providing “assurance” to the Justice Department that they were advancing toward compliance. But they were allowed to make that assurance without having conducted any outside audits; the commissioners protested this in a letter to Mr. Holder in November, expressing concern about “efforts to delay or weaken” adherence to the standards.

In fact, the ambitious goal to audit every prison, jail, detention center, lockup and halfway house in this country over a three-year period is far behind schedule.

Some 8,000 institutions are supposed to be audited for sexual safety by August 2016; only 335 audits had been completed by March, according to a Justice Department document obtained from the office of Senator John Cornyn of Texas; the department declined to provide numbers.

{snip}

But states face only a small penalty, the loss of 5 percent of prison-related federal grants, if they opt out of the process entirely. “There are a lot of carrots in PREA, and not enough sticks,” said Brenda V. Smith, an American University law professor and another former commissioner.

Texas forfeited $810,796–the equivalent of a minuscule fraction of its multibillion-dollar corrections budget–after Mr. Perry declined to sign an assurance letter. According to a spokesman for the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, this loss “will not have any effect on T.D.C.J. operations.”

The other renegade states, as advocates called them, were Arizona, Florida, Idaho, Indiana and Utah.

{snip}

Ms. Star was 19 when she arrived at Telford, with no possibility of parole for a decade. She was quickly inducted into a gang-ruled world with an ultimatum, she said: “You’re going to ride with us, or you’re going to fight.”

“In the state of Texas, in the general population, there is a culture where gay men and transgender women in prison are basically preyed on by the stronger inmates,” she said. “They have to be the property of a person who’s in a gang, and this person is the individual who speaks for them. So basically they’re coerced into being sexually active to survive.”

Ms. Star said that after complaining fruitlessly to prison employees, she submitted to a coerced sexual relationship. She tried to leave the inmate once, she said, but he choked her in response.

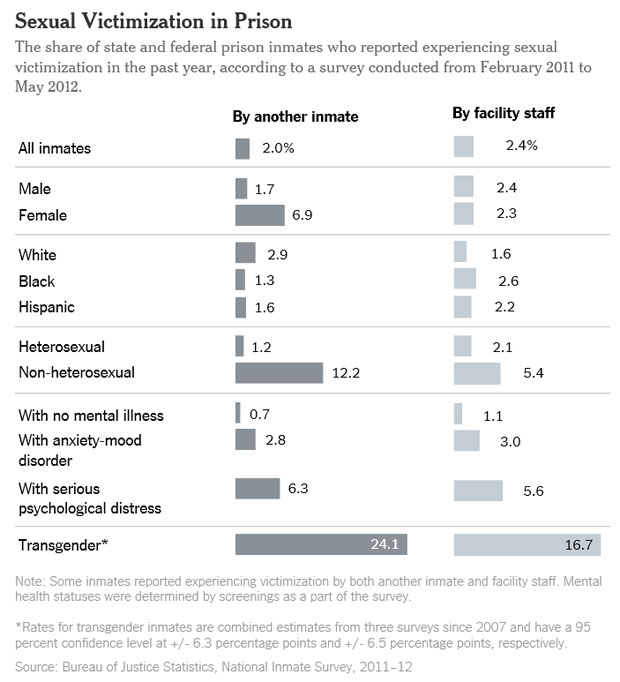

The most recent national inmate survey by the Justice Department found that sexual victimization was reported by 3.1 percent of heterosexual prisoners, 14 percent of gay, lesbian and bisexual prisoners and 40 percent of transgender inmates.

{snip}

As a researcher who studied prison rape when nobody wanted to know about it, Cindy Struckman-Johnson, a social psychologist at the University of South Dakota, was astonished when Congress passed the rape legislation.

“To me it was like a miracle,” said Ms. Struckman-Johnson, a former commissioner who described how she had become “persona non grata” in Nebraska in the 1990s after finding a high rate of prison rape there. “Ever since PREA, nobody can really be in denial.”

The law described prison rape as epidemic. Ideologically evenhanded, it referred at once to “the day-to-day horror of victimized inmates” and to “brutalized inmates more likely to commit crimes when they are released.” It spoke of the potential spread of H.I.V. and of the need for Congress to protect the constitutional rights of prisoners in states where officials displayed deliberate indifference.

{snip}

And indeed, judged through a long lens, considerable progress has been made. That wardens across the country now profess zero tolerance for sexual abuse represents a cultural transformation itself. There are antirape posters on prison bulletin boards, hotlines to report sexual abuse, educational videos for inmates, and training sessions for guards. Statistics show some prisons and jails with very low or even no reported sexual abuse.

{snip}

Yet others are disappointed that the states are moving slowly and that the Justice Department declines to say how much longer it will allow governors to provide “assurances” instead of certifying compliance.

{snip}

In 2006, Ms. Star was transferred to the James V. Allred Unit in Wichita Falls.

Allred would soon be singled out by the Justice Department as one of the 10 most sexually violent prisons in the country. Five of the 10, in fact, were in Texas, and Ms. Star would end up doing time in three of them.

{snip}

At Allred, when she told a prison official she feared for her life after refusing sexual demands, the official told her she would be fine because she is black, she claims in her lawsuit. Over the years, she came to believe the system’s protection program was racially discriminatory.

A racial breakdown of the inmates in safekeeping, provided by Texas, indicates she may have had a point. Of the 1,569 inmates with that status now, 57 percent are white, while whites constitute 30 percent of the inmate population. Twenty-three percent in safekeeping are black, compared with 35 percent over all, and 19 percent are Hispanic, compared with 33 percent.

{snip}

Texas has a very low rate of substantiating allegations. Of 743 reports of sexual assault and abuse in the 2013 budget year, 20 cases, or 2.7 percent, were corroborated; the national rate is 10 percent. One prison rape case was sent to a grand jury that year.

{snip}