He Wears Skins; We Wear Veldskoens

Dan Roodt, American Renaissance, April 14, 2009

On April 2, the Zulu leader and president of the African National Congress (ANC), Jacob Zuma, met with Afrikaner leaders at the Hilton Hotel in Johannesburg. He shocked many blacks and English South Africans alike when he said: “Of all the white groups that are in South Africa, it is only the Afrikaners that are truly South Africans in the true sense of the word. . . . They are here to stay.”

Does this mark the beginning of a historic alliance of two groups–Zulus and Afrikaners–who are often brushed aside by the ANC?

A veteran critic of Afrikanerdom, Allistair Sparks, once said that black rule came about in South Africa because the notion of Afrikaner sovereignty had been abandoned by former president F.W. De Klerk and his moribund National Party in the 1990s. The Afrikaner quest for freedom and independence had fuelled the Great Trek, two wars of independence against Britain, as well as the republican movement during most of the twentieth century. For the last ten years, however, it was almost as if Afrikaners had disappeared from South Africa. As part of Thabo Mbeki’s Africanist revolution–he was president from 1998 to 2008–all sorts of revanchist elements were settling historical scores with the Afrikaners. White English liberals and leftists, Natal Indians, and petty local municipal chiefs have all be hard at work.

Some of the worst damage was done while Kader Asmal was Minister of Education in the ANC government from 1999 to 2004, when he succeeded in all but eradicating the Afrikaans language from university education. Of course, Mr. De Klerk’s deluded followers among the Afrikaners were enthusiastic participants in this process of destroying their own heritage and identity. The heads of Afrikaans universities, especially, acted like quislings, helping Mr. Asmal to destroy Afrikaans as a language of culture and learning. Mr. Zuma’s rise to power and new-found affinity for South Africa’s hated white tribe have changed all that. He has become almost an honorary Afrikaner, since he is vilified to a similar degree by both the British and the local English-language media.

It is not all that hard to see why. Mr. Zuma is a colorful figure who probably could not become head of state anywhere but in Africa. He is a former anti-apartheid guerilla leader whose theme song is “Bring Me My Machine Gun.” He was Thabo Mbeki’s deputy president until 2005, when he was fired because of alleged corruption. The case against him dragged on until just this month, when charges were finally dropped. Mr. Zuma, who had gotten revenge for his firing by toppling Mr. Mbeki as ANC party leader in 2007, argued that he had been framed by political enemies.

Mr. Zuma was also tried in 2005 on rape charges, but acquitted after the woman was unable to prove that the encounter was not consensual. There was considerable public derision over the fact that Mr. Zuma admitted that he knew the woman was HIV-positive but claimed he had taken necessary precautions after unprotected sex by showering. In a typical absurdist post-script to the case, the woman who brought the charges, Fezeka Kuzwayo, was granted asylum in the Netherlands in 2007. She convinced the Dutch she was in danger from Mr. Zuma’s supporters.

Such, then, is the man who is likely to become South Africa’s head of state if, as everyone expects, the ANC wins the general election on April 22.

The main force driving the rather straight-laced Afrikaners and Jacob Zuma into each others’ arms is the age-old political logic of “my enemy’s enemy is my friend.” Apart from Mr. Zuma’s impressive following among Zulus and ordinary black South Africans, he enjoys almost no support or sympathy among local and international elites. As a Zulu, he is also something of an odd man out in a party now dominated by Nelson Mandela’s Xhosa tribe. Afrikaner support would be very useful to him.

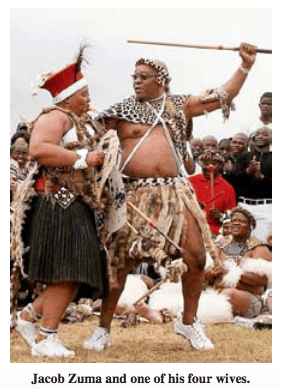

There are other factors that draw him to the white tribe. Mr. Zuma occasionally wears traditional Zulu dress, which is frowned upon in a country where mainstream political commentators have declared that ethnicity is dead.

The Afrikaners in turn remain attached to their ways: According to the Concise Oxford Dictionary, a “veldskoen” can be either a shoe or a “South African conservative or reactionary,” and some Afrikaners have begun to see Mr. Zuma as something of a conservative.

If Mr. Zuma continues his overtures toward Afrikaners, a large portion of the Afrikaans intellectual, academic, and even business elite may support him and bolster his defenses against the almost hysterical campaign waged against him by what we call the “Afro-Saxon” and Anglo-Saxon elites. Assuming that Mr. Zuma takes office as president on April 22, he will inherit a public sector packed with Mbeki supporters who might still try to undermine him. Corruption is rife in the public sector and is partly contributing to the steady collapse of South African infrastructure. Mr. Zuma will need Afrikaans expertise and discipline if he is to uproot corruption and tackle the crisis of governance, especially at the local level.

Mr. Zuma also appears to be sensitive to food security. Mr. Mbeki and his minister of land affairs, Lulu Xingwana, squandered billions in tax revenue appropriating mostly Afrikaner-owned farms and taking them out of production. The millers and supermarket owners applauded this destruction of Afrikaner agriculture because it would finally let them shop for the cheapest produce on the international market. South African wheat growers have virtually abandoned production and we now import lower-quality wheat from Argentina.

A new romanticism holds that the world should abandon large-scale industrial farming of the kind perfected by the Afrikaners in favor of traditional peasant farming on small plots, using primitive and therefore “green” methods. US and British foundations, as well as the local English universities, have long embraced this philosophy and would like to see Afrikaans farmers removed from the land. Such a move would also sound the death-knell for the Afrikaners’ age-old dream of a separate sovereign state, as they would no longer own or occupy much land in South Africa.

However, as Oxford economist Paul Collier wrote in a recent issue of Foreign Affairs, rising food prices are a major threat to the poor, especially Africans. Despite singing about machine guns, Mr. Zuma is a realist who acknowledges the limitations of global romanticism and African-style “agrarian reforms” of the kind that are destroying Zimbabwe.

Food–like oil–has become a strategic resource. A famine-stricken South Africa would invite intervention by America and Britain and put Mr. Zuma’s presidency in peril. Mr. Zuma therefore needs those veldskoen-wearing Afrikaans farmers as much as they need him to stop the revolution emanating from South Africa’s three or four large cities. Driven by Mr. Mbeki’s pan-African philosophy of the African Renaissance and illegal immigration, those cities have adopted a cultural ideal reminiscent of the chaos of a Lagos hotel lobby, and see both Afrikaners and Zulus as unwanted relics from the past.

The strategic synergy between the Zuma-led ANC and Afrikanerdom is clear: the one has political clout in the form of numbers and populist appeal, the other has know-how and technical expertise, as well as agricultural capacity that could ensure South Africa’s independence.

This article is an adaptation of an opinion piece that appeared in the South African publication Business Day.