Ernst Jünger’s 20th-Century Life

F. Roger Devlin, American Renaissance, January 17, 2025

Subscribe to future audio versions of AmRen articles here.

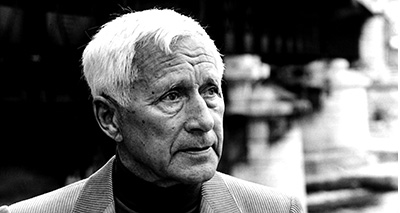

Image credit: © Ulf Andersen/Aurimages via ZUMA Press

Dominique Venner, Ernst Jünger: A Different European Destiny, Arktos Media, Ltd., 2024, 212+xvii pages, $23.95 paperback

The German writer Ernst Jünger (1895-1998) remains relatively unappreciated in the English-speaking world despite the availability of his major works in translation. In France as well as his native land, however, he has long been regarded as one of the major German authors of the last century. His life and works not only spanned almost the whole of the 20th century but, as he himself once remarked, seemed to resonate with its momentous events like a seismograph. As Dominique Venner — of whom more later — writes: “Ernst Jünger is the witness of the successive faces of European destiny throughout this cruelest of centuries.”

Jünger was from German peasant stock on both sides. He was a clever but undisciplined student who could not be made to study anything that did not happen to interest him. What did interest him was literature, especially anything of an adventurous or exotic cast: Karl May’s tales of the American West, Jules Verne, Alexandre Dumas, The Arabian Nights, the Icelandic Eddas. He acquired a good grounding in Greek, Latin, and French. He spent much of his free time exploring a nearly uninhabited stretch of marshy countryside in the company of his younger brother.

At 18, Jünger ran off to join the French Foreign Legion, imagining it would be a ticket to adventure in Africa. He ended up performing routine chores at a barracks in Sidi-bel-Abbès, Algeria. After three weeks, he absconded but was promptly brought back with the help of natives, who received bounties for such assistance. When his father learned that Ernst was locked up in a regimental prison, he travelled to the Foreign Affairs Office in Berlin and got him repatriated on the plea that he was still a minor and had lied about his age.

The adventure Jünger wished for was soon to come to him unsought in the form of the Great War. He quickly joined a rifle regiment, got several weeks of intensive training, and was shipped off to France in the last days of 1914. He took along a small notebook to record his impressions: “I knew that the things awaiting us were unique, and I was heading towards them with great curiosity.”

Jünger saw heavy action, receiving his first wound in April 1915. After convalescence, and at his father’s insistence, he underwent further training to become a commissioned officer. The following year, he took part in the Battle of the Somme, during which he was wounded twice and received the Iron Cross First Class. Altogether, he received 15 wounds, the last while evading British encirclement in August 1918. Shortly before the war’s end, Lieutenant Jünger received the Order of Merit, Germany’s highest decoration.

Over four years of fighting, he accumulated sixteen volumes of diaries “still plastered with the dried mud of the trenches and covered with dark stains that I could no longer determine to have been blood or wine.” He edited them into a book, Storm of Steel (1920), a remarkable testimony to the Great War as actually experienced by one of its combatants. It remains Jünger’s most widely read work and is the basis of his subsequent literary reputation. Over the next few years, there followed a series of shorter books highlighting various aspects of the conflict: War as an Inner Experience, Copse 125, and Fire and Blood — works produced against a backdrop of national defeat and humiliation. But as Dominique Venner notes:

In vain we would look for a single word of resentment, a single trace of hatred for Germany’s enemies of yesteryear. On the contrary, what we encounter is evident esteem and even sympathy for those whom Jünger had fought against with unbridled fury. Indeed, going back thirty centuries to reconnect with the ethos of the Iliad, he is willing to acknowledge that his adversary is also within his rights. When one understands this, “one honors heroism; one honors it everywhere and above all among the ranks of one’s enemy.”

Jünger had no patience with pacifists, however, who regard war “as a material affair” and therefore reduce it to “devastated towns and frightful sufferings:”

There are higher realities to which [war] is subject. When two civilized peoples confront one another, there is more in the scales than explosives and steel. All that either holds of any weight is in the balance. Values are tested in comparison with which the brutality of the means must — to anyone who has the power to judge — appear insignificant.

None of this prevented Jünger from describing the horrors of combat, all of which he had experienced personally, with perfect honesty and precision. As Venner writes:

His aim is neither to shock nor to please. The conclusions that he draws from the ordeal are not, however, fraught with despair or resignation. What we readily notice in them is a “Heraclitean” type of contemplation of the challenges imposed on men through the ages, challenges that occur in the framework of a cosmic struggle that will never come to an end.

Germany’s surrender in November 1918 coincided with the overthrow of the Hohenzollern monarchy and the establishment of the so-called Weimar Republic. In its first five years, the new government barely managed to contain a series of violent uprisings by the radical Left, the German equivalent of Russia’s Bolsheviks. It weathered this storm with essential help from the so-called free corps, unofficial military formations consisting of nationalist youth and former soldiers who had little love for the social democratic republic they saved. Jünger sympathized with these men, later writing: “It turned out that Germany still had a type of man that could be counted on and that was equal to the task of overcoming anarchy.” He did not participate in their struggles, however, since he stayed in the Reichswehr, the military of the German Republic, until August 1923.

Toward the middle of the 1920s, the regime stabilized, and political conflict moved from the streets to the printed page. Countless nationalist journals emerged advocating often radical political programs for the pursuit of essentially constructive and patriotic ends, a phenomenon later given the paradoxical label “the conservative revolution.” Jünger played an important role in this movement, publishing many articles between 1925 and 1930. His thinking was closest to the “national revolutionary” current, which advocated cooperation with Soviet Russia. As Venner explains, this was not motivated by any sympathy with Leninist Communism but by an older Prussian tradition of Russophilia: “To those close to the National Bolshevik movement, Russian communism was only superficially Marxist in nature. It seemed to be, above all, a Russian phenomenon.” These thinkers believed that a nation’s spirit, or Volksgeist, was something permanent that would always prevail in the end over the more superficial contingencies of politics.

Many of his political allies, though not Jünger himself, came from the Left. They parted company with orthodox Marxism, however, in teaching that the main enemy of the German worker was not the German employer but international finance capital as embodied in the victors of the Great War. Accordingly, they wanted an alliance between Germany and Russia as the two “proletarian nations” against a capitalist West. For a brief time, such thinking was influential even within the rising National Socialist movement in the person of Gregor Strasser, head of the party in Northern Germany, though he would soon be overruled by Hitler.

In general, the period of the Conservative Revolution was marked by a complete absence of impervious barriers between Right and Left, and the distinction was meaningless to Jünger himself. He was, for example, especially close to Ernst Niekisch during these years, a man who ended up moving to East Berlin after 1945 and working for its Soviet-installed government. Through Niekisch, writes Venner, Jünger “made the acquaintance of the pacifist Ernst Toller, the anarchist Erich Mühsam, and the Marxist Georg Lukacs.”

Toward the end of the 1920s, Jünger’s works begin to reflect what Venner calls “a clear withdrawal into the inner sphere of reflection . . . . He had stopped believing in the resources of collective action.” The journalistic ferment of the Conservative Revolution also began to give way to the rise of radical political parties. In the German elections of September 1930, amid a worldwide economic crisis, Hitler’s National Socialist Party had an eightfold increase in support, and the Communists also registered significant gains. It became clear that the moderate Republican center would not be able to hold.

Jünger later recalled his first encounter with Hitler and his movement:

I barely knew his name when I saw him in a Munich amphitheater, where he delivered one of his very first speeches. I was captivated, as if I were undergoing some sort of purification. Our immeasurable efforts during those four years of war had not only led to our undoing but also to humiliation. Our now disarmed country was surrounded by dangerous neighbors armed to their teeth; it was fragmented, pillaged, bled dry. It was a sinister vision, a vision of sheer horror. And now we looked on as a stranger rose up and told us what had to be said, and everyone felt that he was right. And it wasn’t a mere speech he was giving, for he embodied a manifestation of the elemental, and I had just been swept away by it.

In 1925, Hitler sent the author of Storm of Steel a copy of his newly published manifesto Mein Kampf; Jünger thanked him by sending along one of his own books inscribed “To Adolph Hitler, the Führer of the Nation! Ernst Jünger.”

Despite their common dedication to a revolutionary renewal of the German nation, this friendliness did not last. Venner devotes a chapter to contrasting Jünger’s views with Hitlerian ideology. He ascribes to Jünger “a highly spiritual Prussian idea of the State conceived of as being a chivalric order,” in which freedom was perfectly synthesized with service. The philosopher Oswald Spengler explained the Prussian ideal as follows:

To be free — and to serve: there is nothing more difficult than these two things; only peoples whose mind and very being is rooted in such capacities have the right to aspire to a great destiny. Serving — therein lies the style of ancient Prussia. There is no “I” but a “We,” a collective feeling to which everyone commits his entire existence. The singular is of little importance and must sacrifice itself in the name of the Whole. Inner freedom in the noble sense, libertas oboedientiae, freedom in obedience, has always characterized the best elements of Prussian education.

By contrast, writes Venner, Hitler’s “systemic mind, ever on a quest for absolute truth, was dazzled by” the popularized racial Darwinism of his youth, from which he drew a

categorical imperative endowed with all the violence of religious extremism. This is what makes Hitler akin to Lenin, for whom “science” had replaced the certainties derived from the word of God. And since science and the future ordered him to do so, Hitler would, just like the Marxists, implement his plan without any regard for the suffering and damage that he would trigger.

Venner quotes only one racially tinged remark of Jünger’s, a sarcastic reference from 1929 to “humanism’s attempts to honor man in every bushman rather than in us.” He notes that “like his contemporaries, Jünger was well-aware of the importance of being ‘well-bred’ within the framework of a nation’s necessary breeding ground. Unlike Hitler, however, he did not consider this to be the sole explanation behind everything.” Venner ascribes to Hitler the belief that “it was enough to apply eugenic measures and erect barriers against miscegenation so that the virtues of old could return and the Aryan, the creator of a higher form of civilization, could automatically resurface.” He contrasts such simplifying fanaticism with a more traditional view of race, which

without neglecting the factors of physical improvement and degeneration, do not believe in human advancement in line with a general evolution of the species, but through constantly repeated personal and civilizational improvements stemming from an effort to surpass oneself. Ernst Jünger sensed that, like Marxism, Hitlerism was a distortion of Enlightenment rationalism, a sort of madness-afflicted reasoning. What had once been experienced as immemorial, accommodating, and flexible wisdom would be imposed with geometric rigor by legions of narrow-minded officials. . . . Nowhere in Jünger’s work does one find a single trace of the racial Darwinism that characterizes Hitlerian National Socialism.

The National Socialists were also suspicious of Jünger, and began publishing scathing reviews of his works, one of which even predicted he would end up “being shot in the back of the neck.” In April 1933, Jünger’s house was raided by local police, and in fear of possible future raids, he took the precaution of destroying his diary of the years preceding the advent of the Third Reich. Venner calls this “a great loss that deprives us of the milestones that could have allowed us to get a better understanding of his evolution at the time.” Jünger opted for what is sometimes termed “inner emigration,” remaining in Germany but quietly keeping his distance from those in power. He was particularly outraged by the purge of June 30, 1934, commonly known as the “Night of Long Knives,” whose victims included men he knew well.

In September 1939, shortly after Germany’s invasion of Poland, Jünger published a short allegorical novel entitled On the Marble Cliffs. The plot, as Venner writes, centers on two brothers living in an imaginary country

invaded by barbaric and bloodthirsty forces. At first, the brothers’ belligerent past leads them to resort to the use of weapons. Later on, however, while reflecting on things in the depths of their hermitage, [they] come to the conclusion that “there are weapons stronger than those which cut or stab,” and decide to “resist with spiritual forces alone.”

The allegory was not difficult to penetrate, and the book was “immediately perceived as a coded condemnation of the regime.” Even the second brother was an obvious allusion to Jünger’s own younger brother Friedrich Georg, a talented writer in his own right. On the Marble Cliffs proved popular, selling over 30,000 copies within a few months. Joseph Goebbels wanted the author arrested, but Hitler overruled him: “No one touches Jünger!”

The 44-year-old Jünger was recalled to the colors as commander of an infantry company defending the Siegfried Line against possible French attack. When Germany invaded France in May 1940, he took part in the capture of Laon and protected its medieval library from pillaging. In the spring of 1941, he was assigned to the occupation forces in Paris. Here he enjoyed the protection of Col. Hans Speidel, an admirer of his writings and “the very soul of a small circle of officers united by the same veiled hostility toward Hitler’s policy.”

Apart from the administrative or military duties, Jünger enjoyed considerable freedom, which he spent exploring the Parisian artistic and literary scenes, recording his impressions in journals. He became a regular at the salon of Florence Gould, a wealthy woman who managed to treat her guests to “lavish meals washed down by the best wines and accompanied by genuine coffee,” as if there were no war or occupation. At her soirées, Jünger encountered “every manner of people, including collaborators, Pétainists, members of the resistance and those who chose to remain indifferent.” (After the liberation, Mme Gould saved her skin with “generous donations” to the French Resistance.)

Ernst Jünger in Paris, 1941.

France, in turn, was now discovering Jünger, who had been previously little noted there. His works, including the dissident allegory On the Marble Cliffs and his Parisian journals, quickly began appearing in French translation. The French fascination with Jünger proved lasting, and a lavishly annotated edition of his war journals has even appeared in the prestigious Bibliothèque de la Pléiade.

After Germany’s loss at Stalingrad, the one-time despiser of pacifism began drafting a short manifesto entitled Peace, intended to serve as a call to the youth of Europe and a guide for the opposition. Venner considers the work’s expressed hope of peace through compromise “completely illusory” and writes that “its pitiful justifications and humanitarian platitudes summarize the intellectual chaos which Europe would have to contend with for a long time.” He does concede, however, that Jünger’s Russophile hope for a “transfiguration of the Russian Revolution [that must] be achieved on a metaphysical level” reflects an “endearing sort of naivety.” The work could not be published at the time, of course, but a French edition appeared in 1948.

Jünger was demobilized in August 1944, a few days before the liberation of Paris. Home in Germany in January 1945, he learned belatedly of the death of his eldest son. Early in 1944, the seventeen-year-old naval cadet had been arrested for saying he would gladly pull the rope that would be used to hang Hitler. Jünger managed to obtain leniency for the boy on grounds of youth, in exchange for immediate recruitment into the army, but he was killed on November 29, 1944, in Northern Italy.

Early in 1945, Jünger was assigned to the Volkssturm, a kind of territorial militia established toward the end of the war. On April 3, he ordered the men under his command not to resist the American troops. His diaries record his gradual loss of esteem for his nation’s conquerors, previously based on their common opposition to Hitler. He noted, e.g., the obvious satisfaction with which Allied radio reported atrocities committed against German civilians.

Under the Allied occupation, Jünger was classed as a “nationalist,” which for the Americans meant almost a Nazi, and he was banned from publishing until 1949. In 1951, he produced an essay called The Forest Passage (Der Waldgang) reflecting his attitude to the emerging Cold War era of European dormancy and domination by outside powers. He distanced himself from the “inner emigration” he had adopted under the Third Reich, writing: “To defend oneself against injustice or tyranny, once cannot limit oneself to the sole conquest of interior realms.”

As Venner explains: “The word Waldgänger takes its name from an ancient Scandinavian custom. Any outlaw guilty of murder could be legally slain by anyone who met them. The outcast, however, had the right to ‘take the forest path’ — take refuge in the woods, living freely there at his own risk.” In European tradition, forests have long been portrayed as places of regeneration.

In his 1977 allegorical novel Eumeswil, Jünger sketched out what Venner calls

A new ‘type,’ a new ‘figure’ which one would swear is that of the European forced to remain on the sidelines of history. And it was for him that Jünger coined the term ‘anarch,’ which he hastens to contrast with the anarchist. [The latter] is dependent — both on his unclear desires and on the powers that be. He trails the powerful man . . . whom he dreams of wiping out . . . as his shadow. The positive counterpart of the anarchist is the anarch, [who] is not the monarch’s adversary. He observes the world around with both interest and detachment. What he is concerned about is, in fact, his integrity. Unable to be king of the world, his is the king of his own self. This gives him an attitude both objective and skeptical towards the powers that be.

Jünger adds that “every born historian is more or less an anarch.”

Ernst Jünger lived to the age of 102, and Venner describes the regimen he followed nearly to the end:

Showering in cold water every morning, he would go for a walk through the countryside on a daily basis and indulge in the daily practice of contemplative reading, transcribing his thoughts into his diary and never neglecting the beneficial effects of good wine and sleep. Photos taken on the occasion of his one-hundredth birthday attest to the aristocratic firmness of his very face. And the television interview he granted in French on this occasion highlights the intact vigor of his sarcastic mind.

Ernst Jünger. (Credit: Hoibo, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

In closing, we should say a few words about the author of this study. Dominique Venner was born in 1935, 40 years after Jünger, and his life followed a somewhat similar pattern. When he came of age, he volunteered for combat duty in Algeria, where he was decorated. Following his discharge in 1956, he joined the illegal Secret Army Organization which tried to stop Algerian independence, an involvement for which he served a year and a half in prison. Upon release in 1962, he threw himself into political journalism, creating a movement and magazine called Europe-Action in collaboration with Alain de Benoist. He was also a member of de Benoist’s Research and Study Group for European Civilization (French acronym GRECE) from its beginnings until the mid-1970s.

Dominique Venner

During the 1970s he turned increasingly to writing about history. His first such work was Baltikum, recounting the story of the German Free Corps of the early Weimar period. He sent a copy to Ernst Jünger, the beginning of a correspondence which lasted for more than 20 years. Jünger clearly recognized a kindred spirit in the younger man. This study of Jünger appeared in French in 2009. In 2013, the 78-year-old Venner, outraged by mass immigration and the endorsement of homosexual “marriage” by the French government, publicly ended his life by shooting himself in the head before the high altar of the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris.