Legitimate Preference: A Guide for Our People

Jef Costello, American Renaissance, February 9, 2024

Credit Image: © Imago via ZUMA Press

Subscribe to future audio versions of AmRen articles here.

Tim Vorgens, Legitimate Preference: Who Wants to Lose the Right to Self-Preference? (trans. from the French by the author), Legatum Publishing, 2023, 105 pp., $24.95 (hardcover)

This powerful little book, which boasts a foreword by Jared Taylor, advances a simple but revolutionary thesis: that we have a right to prefer — specifically, a right to prefer our own people. We owe life itself to our racial forebears, as well as the culture that makes our lives meaningful. “Legitimate preference,” writes Tim Vorgens, “could be defined as the disposition of mind which makes us systematically and exclusively favor [our own group], rather than . . . those groups to which we owe nothing.”

The attachment we feel to our own is pre-rational and does not result from conscious choice. Imagine if Big Brother commanded us to love our own children and the children of strangers equally — to stop preferring our children. We would regard such a demand as perverse. And yet, it is this that is expected of us when it comes to our feelings about our extended family, our nation or race.

The situation is actually worse. We are not told that we must love our own people and other peoples equally. We are told that we must prefer “the other” and repudiate our own kind, that we must perpetually wear sackcloth and ashes, in unceasing repentance for the supposed sins of our race. Guilt, we hear over and over, is the only legitimate feeling we can have about our history.

Many whites have been thoroughly cowed by the taboo against preferring one’s own race. Indeed, we have been taught to “adore the other as an ideal,” Mr. Vorgens writes, though only the most doctrinaire leftists seem truly capable of this. They are the people who are willing to put their fellow whites in danger “for the sole pleasure of being elected the most moral community in the world.”

Strikingly, Mr. Vorgens writes of liberals that “they are the flesh that wants to become a concept.” This is a memorable way of calling attention to the fact that leftists seem to live in denial of the body, denying the influence of genetics (on intelligence and other factors), the inherent differences between the sexes, and natural inequalities of all kinds. They are willing to risk their own bodies, and yours too, for the sake of signaling their commitment to the impossible ideal of multiculturalism.

Leftists might deny biology, but their own bodies, like those of all living organisms, seek to survive and flourish — even if their bodies must do so by deceiving their conscious minds. Thus, liberals build what Mr. Vorgens calls “safe spaces” for themselves — for example, living in gated communities with other whites or moving to new locations in search of “good schools.” Mr. Vorgens refers to this as “hypocritical preference.”

Through their actions, even leftists therefore concede that our great multiracial experiment has failed. “So why continue the experiment?” Mr. Vorgens asks. “Why not reclaim our right to Preference? . . . Preferring our fellow human beings and hiring, and renting a property, and accessing services . . . as we already do in the field of love, or in the field of daily relationships.” (Note: Mr. Vorgens often uses the expression “our fellow human beings” when what he actually means is “human beings like us.”)

Mr. Vorgens writes that “In our situation of disenfranchisement, we cannot demand anything less than the right to Prefer.” This is at once an extremely simple idea and, in present circumstances, an extremely radical one. If a black man stated that he preferred to live and work around other blacks, liberals would hardly notice. But woe unto any white man who expresses the same preference for his own race.

We have to state our preference frankly and forthrightly, Mr. Vorgens argues, as if it were the most simple, obvious, and natural thing in the world (which it is): “I prefer living and working with other white people.” And this must be said without the slightest hesitancy or apology. To use one of Mr. Vorgens’s examples, mothers should say, “My kids need doctors who look like them.”

To express such preference, he says, is “just to let our nature speak.” Here, Mr. Vorgens refers obliquely to the power of genetic similarity. We are drawn to others who are genetically like ourselves, and we feel varying degrees of discomfort around those who are genetically dissimilar. F. Roger Devlin has summarized some of the scientific research in this area:

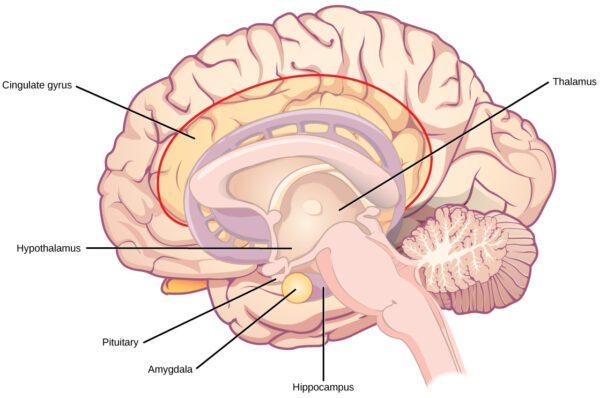

When white and black people are shown pictures of strangers, the amygdala region in their brains displays heightened activity, indicating vigilance or wariness toward unfamiliar faces. But when the pictures are shown a second time only the other-race faces provoke high amygdala activity: the brain perceives the same-race faces as “familiar” after only one viewing.

CNX OpenStax, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Incidentally, researchers have found that conservatives have bigger amygdalae than liberals. Reclaiming the right to prefer means giving your amygdala a “much-needed vacation.” It means being able to breathe and relax. It means being able to leave our houses or cars unlocked and possibly even to leave our babies out on the sidewalk while we have lunch in a café, as they do in Denmark.

Though their amygdalae may object, white people do make a strong effort to direct good will toward “the other.” White benevolence is not entirely a matter of ideological indoctrination. It flows from the qualities of openness, generosity, and curiosity about difference that are Europeans hallmarks. Mr. Vorgens acknowledges this, writing that “white ‘kindness’ must not be eradicated, but contained, framed and re-educated. Legitimate Preference is the framework in which it can be exercised in a non-pathological way.”

Mr. Vorgens does not, however, have much to say about how to accomplish this. Throughout the book, he insists that rational arguments alone are not enough to exhort whites to re-claim the right to prefer. He states that “Being right [i.e., being correct] often leads one to rely on the supposed power of truth, but truth has no power. Truth is not a power. The rationality of our cause is, most likely, not enough on its own.”

I’m not sure I agree that “truth has no power.” I’ve personally witnessed many cases in which people of average intelligence, with little or no claim to being “intellectual,” changed their minds on major issues when presented with simple arguments founded on well-supported premises. Nevertheless, there is no denying the power of rhetoric, and it is really rhetoric that Mr. Vorgens has in mind (though he does not use the term), when he writes, “We must use tools that reach the emotions.”

Surely this is the only path to achieve one of the major goals he sets for himself: to make white preference “trendy” within the next 10 years. And Mr. Vorgens’s own book is certainly charged with emotional power. “Legitimate Preference,” he writes, “makes you realize that you are more than an individual. You are a lineage that crosses time and conquers space.”

This claim will stir something deep within many of Mr. Vorgens’s readers. Yet we all know that many whites would be entirely unmoved. What can we do with such people? Is it possible to teach love of one’s own, including a love of one’s history and lineage, to someone who doesn’t feel it? Maybe not. But if an atrophied remnant of that love slumbers within, surely it is possible to awaken it.

One approach is to offer some version of “white eschatology” — the title of one of the later chapters in Legitimate Preference. Here Mr. Vorgens offers us a vision of the white race as “the promethean people.” By this, he means that whites possess a kind of “racial mission” that amounts to the mastery and control of nature.

Prometheus Bound and the Oceanids by Eduard Müller (1879). Credit: Album / Tolo Balaguer

No other race seems to possess the same infinite striving both to know nature and to transform it. To many, this is inspiring, but it could be our downfall. It may be that prometheanism is both our glory and our tragic flaw.

As Mr. Vorgens notes, white prometheanism has given us “earthquake anticipation, storm forecasting, early detection of cancers, weather monitoring, anti-flood dams, artificial intelligence risk forecasting, pollutant management, concern for ecological changes, etc.” And yet it also proclaims that even though multiculturalism has always led to the downfall of civilizations, this time we will get it right. Prometheanism has such confidence in its powers that it wants to phase out fossil fuels before we find viable alternatives. It is prometheanism that brought us gain-of-function research and “sex change” operations. We hear its siren song when college professors declare that “real communism has never been tried.” All these follies have been brought to you by “the promethean people,” that is, white folks.

Oswald Spengler was arguably closer to the mark when he called European man “Faustian.” Our tremendous strides in knowledge and mastery do indeed seem a bit like a deal with the Devil, since they have ushered in modern hubris that sees nature as infinitely malleable and man as its measure.

Dr. Faustus conjuring up Mephistopheles. (Credit Image: © PHOTO12 via ZUMA Press)

It is modern prometheanism, in fact, that is at the root of the Left’s denial of all natural limits and its conviction that everything is open to subjective human choice. We need to have a more nuanced view of our promethean nature than Mr. Vorgens offers.

Mr. Vorgens’s “white eschatology” also bears more than a passing resemblance to William Pierce’s “cosmotheism.” Pierce was prompted to develop cosmotheism when a high school student asked him, “Why do you think it’s so important for the white race to survive?” In response, he argued that the universe is evolving toward consciousness of itself and that the white race is the vehicle of that cosmic self-awareness, principally through science.

In other words, science is nature knowing itself — and science was created by, and continues to be dominated by, white men. William Pierce’s theory is intellectually exciting (though it is essentially just a warmed-over version of Hegel’s philosophy). Cosmotheism presents a case for why the white race is worth saving. But is it successful as a way to exhort whites to save themselves?

Mr. Vorgens is correct when he says we need to awaken “self-preference” in whites — or, better still, self-love, love of one’s own. But love is not based on reasons or justifications. Men don’t love their children because they’re rationally convinced that they are the best children in the neighborhood. They love their children simply because they are their own.

We must, as Mr. Vorgens argues, reclaim the right to prefer our own, without apology, but also without justification. If I tell people I prefer to live and work around other whites, and they ask, “Why?” it is an entirely legitimate response simply to say I just do. Other races don’t need a “reason” for preferring their own. They just do.

Nor do we need to spin grandiose myths about the white race to justify our love for it. A love that we feel the need to justify is a weak love. A religious man who feels the need to supplement his faith with rational arguments for God’s existence is, whatever he may tell you, suffering from a crisis of faith. True love, like true faith, requires no justification.

Legitimate Preference concludes on a surer footing, with a chapter titled “The Fifteen Rules.” Here Mr. Vorgens sets forth a kind of ethics for white nationalism. He argues that we need to cultivate three qualities: intolerance, opportunism, and clannishness. These are all self-explanatory save, perhaps, “opportunism,” by which Mr. Vorgens means seizing “what offers an advantage to our compatriots.”

These three are usually seen as vices. Yet, they are essential to the continuance and flourishing of an ethnic group — and only groups that cultivated these ethnic “virtues” have survived through centuries of change. Jews are undoubtedly the best illustration of this.

Mr. Vorgens invokes the Greek concept of storgē, which means “familial love,” in contrast to eros (erotic love), philia (love of friends), and agapē (love for humanity as a whole). For the ancients, storgē commonly referred to the love between parents and children, but it can include an extended family or clan. Mr. Vorgens writes that “Storgē at its maximum size (that of the entire racial vessel) becomes the Legitimate Preference.” To safeguard our race and culture and promote its flourishing, storgē — the pursuit of our common good — must become our morality, he argues, and “we must abandon everything else.”

I will not discuss in detail the 15 rules that follow, aside from mentioning a few examples. Readers will surely agree with the first rule: “Every individual in the Preferential family must favor the creation of harmonious white homes [i.e., homelands] for himself and then for his fellows, as soon as circumstances permit.”

The second rule tells us that our preference for other whites must take precedence over all sympathies we might have for others. The third enjoins us to be honest and open with our fellow whites and to “save cunning for [those outside] the community, when necessary.”

Mr. Vorgens is clearly speaking to the young men in our movement who seek in white nationalism a “way” — a discipline and a hard path — when he calls for “a cult of health, body, knowledge, heroics, and positive eugenics,” and tells us that “the link between Europeans of the past, present and future, is to be the object of regular meditation.”

We are asked (rule ten) to become role models, especially for the young, by “confronting them with our unabashed Preference.” Other elements are less clear, as when Mr. Vorgens calls on us to “Reduce the gap between scientific discovery and understanding of the world,” and when he speaks of cultivating a “vitalist metaphysics,” though the idea is intriguing.

There is a great deal of good advice here and much that can provide inspiration for those on our side. Legitimate Preference is brimming with ideas, and it is written with great passion. Tim Vorgens’s text is clearly a labor of love — born of “legitimate preference,” or love of one’s own.

Some ideas are less clear and less persuasive than others. Also, Mr. Vorgens has translated the book into English himself, and there are a number of errors of usage. While the author’s meaning is usually clear, the reader scratches his head over some sentences.

In this age of print on demand, it is not too late to correct that problem. I recommend that the publisher find a native English speaker to revise this translation.

Setting aside these minor reservations, there is much in Legitimate Preference that anyone in our movement can profit from.