The White Death

F. Roger Devlin, American Renaissance, May 8, 2020

Anne Case and Angus Deaton, Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, Princeton University Press, 2020, 312+xii pages, $27.95 (hardcover)

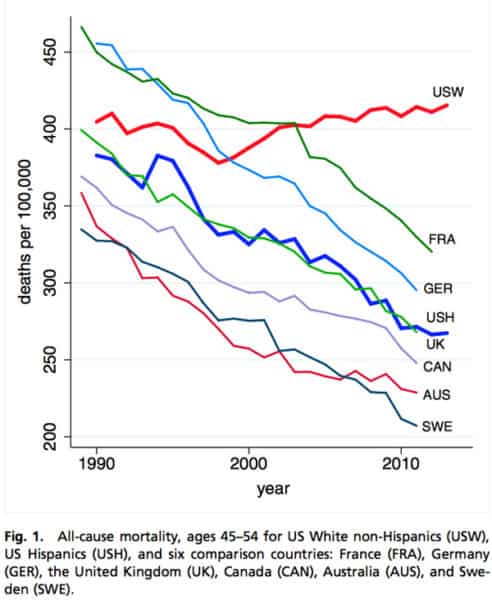

Anne Case and Angus Deaton are a married couple, both Princeton economists. In the summer of 2014, they were researching suicide statistics and noticed that the rate for middle-aged white Americans was rising rapidly. They wanted to get a better understanding of this trend, and downloaded overall mortality statistics from the Center for Disease Control:

To our astonishment, it was not only suicide that was rising among middle-age whites; it was all deaths. We thought we must have hit a wrong key. Constantly falling death rates were one of the best-established features of the twentieth century. Even a pause was news. All-cause mortality is not supposed to increase for any large group. [2]

Most of the increase not due to suicide turned out to be coming from drug overdoses and alcoholic liver diseases. These three causes of death have something important in common: They are self-inflicted — all at once in the case of suicide and more gradually in the case of alcohol and drugs. The authors call them “deaths of despair.” For white men and women aged 45 to 54, the incidence of such deaths more than tripled from 30 per 100,000 in 1990 to 92 per 100,000 in 2017. The authors also learned that deaths of despair are heavily concentrated among the two-thirds of Americans without a four-year college degree; college graduates are mostly exempt.

Profs. Case and Deaton did not find a willing academic audience for the information they had uncovered, as they explained in an interview with the Washington Post:

Deaton: Anne presented the first paper once and was told, in no uncertain terms: How dare you work on whites.

Case: I was really beaten up.

Deaton: And these were really senior people.

In their new book, the authors are careful to acknowledge that blacks have always had, and still have, higher mortality rates than whites. They are probably not familiar with J. Phillippe Rushton’s argument that blacks are less K-selected than whites, and therefore may be expected to have a somewhat higher mortality rate, so they attribute the difference to “discrimination” and “white privilege.” But they also point out that black mortality rates are still falling:

In the past three decades, the gap in mortality rates between blacks and whites with less than a bachelor’s degree fell markedly. Black rates, which were more than twice those of whites as late as the early 1990s, fell as white rates rose, closing the distance between them to 20 percent. [6]

The rise in midlife white mortality began in 1999, and by 2017, 600,000 Americans in this category had died who would have been alive if mortality had continued to decline as before. For comparison, the authors mention that HIV/AIDS has claimed 675,000 American lives since the early 1980s. The “white death” may be killing a less fashionable set of people, but it represents a comparable catastrophe.

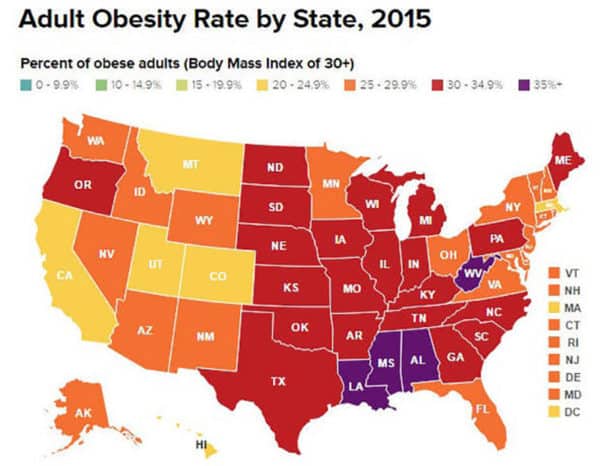

Next, Profs. Case and Deaton looked at geography, to determine where mortality rates for mid-life whites had risen the most. The worst hit state was West Virginia, followed by Kentucky, Arkansas, and Mississippi. At the opposite extreme, the only states not to have experienced any significant rise are California, New York, New Jersey and Illinois: all home to large cities with above-average levels of schooling.

A critic of the authors’ earlier papers on white mortality pointed out that even the rise in overdoses, suicides, and alcohol-related deaths put together did not account for the total rise in white mortality. In their new book, Case and Deaton point to “a marked slowdown in progress against mortality from heart disease” [41] as the missing factor; it accounts for 15 percent of the rise. Heart disease has many underlying causes, some of which overlap with deaths of despair. Heavy drinking, for example, can lead to heart disease by raising blood pressure and weakening the heart muscle, so some portion of deaths attributed to heart disease are also alcohol-related. Certain drugs, particularly cocaine and methamphetamines, are also very bad for the heart. But opioids are far more heavily implicated in rising white mortality, and the evidence for their effect on cardiac health is equivocal.

The most common cause of heart disease is obesity, sometimes acting by way of diabetes. The authors rightly point out that:

eating too much, like drinking too much, is for some people a reaction to stress and a way of self-soothing in the face of life’s difficulties and disappointments, so deaths associated with obesity could perhaps also be included in deaths of despair. [43–44]

(Note the recent popularity of the expression “comfort food,” an expression I never heard in my youth.)

Profs. Case and Deaton do not mention this, but a quick look at American obesity statistics shows that the list of most overweight states are largely those with the highest white mortality: West Virginia, Mississippi, and Arkansas are in the three top spots, while Kentucky is fifth, behind Louisiana. In America, obesity is also associated with poverty and lower levels of schooling. The authors do not explore this angle in detail.

Credit Image: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation / Trust for America’s Health via The Boston Globe

The white death is now expanding beyond its beginnings among middle-aged Americans, with deaths of despair accelerating among the young. The pre-boomer generation appears exempt, but mortality rates among the elderly are now rising as boomers shift into that category.

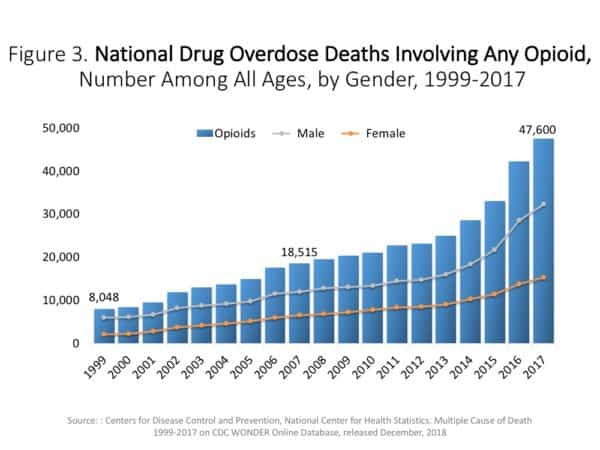

The opioid epidemic

Accidental drug overdoses, primarily of opioids, are both the largest and the fastest growing of the three main kinds of midlife deaths of despair. The spike in drug-related deaths began around 1990 with the movement to devote more medical attention to combating pain. In that year, Ronald Melzack published an influential paper called “The Tragedy of Needless Pain,” in which he argued that “when patients take morphine to combat pain, it is rare to see addiction.” Previously, pain had usually been treated with a combination of non-opioid medications, counseling, and exercise. The system was time-consuming, however, and doctors increasingly work under severe time and financial constraints. This made simple, effective pain pills attractive.

In 1995, The US Food and Drug Administration approved the prescription painkiller OxyContin, manufactured by Purdue Pharmaceuticals, legalizing what was essentially a form of heroine.

Its twelve-hour slow-release mechanism, it was claimed, allowed sufferers to sleep through the night. Unfortunately, in a large share of users, pain returned and opioid withdrawal began well short of the twelve-hour mark, and many physicians responded by shortening the interval to eight hours or increasing doses. The cycle of relief followed by pain and withdrawal increased the risks of abuse and addiction. [117]

Doctors and dentists began prescribing OxyContin and similar drugs (Percocet, Vicodin) for all kinds of routine pain, and addiction and overdoses began to rise. To get a sense of the sheer scale of abuse in the worst-hit areas, consider that over one two-year period, 9 million pain pills were shipped to a single pharmacy in Kermit, West Virginia, population 406. In many cases, doctors did not even hear when patients died from drugs they had prescribed.

By 2011, the annual death count for prescription opioids reached 14,583. The rate began sinking thereafter, as awareness of the problem grew and Purdue reformulated OxyContin to make it more abuse-resistant. But by then it was too late: Illegal drug dealers began lurking outside pain clinics, looking for patients who had been denied refills. Total opioid deaths continued to rise even as deaths from prescription opioids began to fall.

When the US Drug Enforcement Administration tried to stop the abuse, Congress countered with the 2016 Ensuring Patient Access and Effective Drug Enforcement Act. Proponents of the new easier-access law even included Congressmen from districts heavily hit by opioids: “[M]oney and pro-business ideology subordinated the voices of those who had been addicted or were dying.” [125] A revolving-door operated between government and pharma: One senior DEA lawyer switched sides to advise the industry and help write the bill. The more cynical lobbyists refer to congress as the “farm team” that feeds the more serious business of lobbying.

Until 2019, at least, when rising public outrage finally boiled over, those who got rich were neither ostracized nor condemned, but seen as successful businesspeople and philanthropists. The Sacklers, owners of Purdue Pharma, saw their name appear on:

museums, universities, and institutions, not only in the US but also in Britain and in France. Most of the organizations have stopped using the Sackler name — sometimes after resisting the step for years — and others have said that they will accept no more money. [128]

Another sign of the times: In May 2019, five top executives of Insys Therapeutics were convicted on federal racketeering charges. Their salesmen were bribing doctors to prescribe fentanyl, a drug over 30 times as strong as heroin, to patients who did not need it.

Fentanyl (Credit Image: Crohnie/Wikimedia)

Lawsuits will probably bankrupt some pharmaceutical companies. Others may simply raise prices so that ordinary users end up footing the bill, providing little incentive for the companies to change: “[O]nly admissions of wrongdoing and criminal verdicts against the executives are likely to do that, and such verdicts, although not unknown, are rare.” [130]

Furthermore, the best way to help addicts is known as medication-assisted treatment (MAT), in which those with addictions use different opioids to control their cravings as they quit. This means that the pharmaceutical companies that made so much money from the opioid crisis now stand to profit from treatment: “[I]n the summer of 2018, Purdue Pharmaceutical was granted a patent for a variant of MAT, setting itself up to repeat its earlier success with OxyContin.” [129]

The authors add this caveat:

The supply side of the [opioid] epidemic was important — the pharma companies and their enablers in Congress, the doctors who were imprudent with their prescription — but so was the demand side — the white working class, less educated people whose already distressed lives were fertile ground for corporate greed, a dysfunctional regulatory system, and a flawed medical system. [126]

Declining health

Rising white working-class mortality has been accompanied by a more general decline in health, but this is harder to quantify since there are so many different ways to be sick. A common method is to ask people to characterize their own overall health as excellent, very good, good, fair or poor. Crude as it sounds, such self-reporting yields useful information: “The answers tend to match up with other measures, including objectively verifiable measures.” [75]

Profs. Case and Deaton learned that white Americans without a bachelor’s degree were almost three times more likely to report poor health than those who had completed college. They also found that the self-reported health of those without a degree declined markedly between 1993 and 2017: Among 40-year-olds, e.g., the percentage of Americans reporting poor health doubled from eight to 16.

The National Health Interview Survey also carries out large-scale surveys on serious mental distress, asking Americans how often they feel sad, nervous, restless, hopeless, worthless, or that “everything was an effort.”

Around age fifty, the percentage of whites without a bachelor’s degree in severe mental distress rose from 4 to 6 percent from 1997–2000 to 2014–17. The fraction of whites without a bachelor’s degree who express difficulty in going out to do things like shop or go to the movies and the fraction finding it hard to relax at home have increased by 50 percent for those aged twenty-five to fifty-four, and the fraction finding it difficult to socialize with friends has nearly doubled in this twenty-year period. [79]

More working-class American whites are also reporting an inability to work (as opposed to merely being out of work):

For those aged forty-five to fifty-four, historically the peak earning years, the percentage of whites reporting that they were unable to work rose from 4 percent in 1993 to 13 percent in 2017 for those without a bachelor’s degree. The percentage for those with a four-year degree was initially low and remained so, between 1 and 2 percent. [80-81]

This is a lot of distress, and deaths of despair are just its most extreme expression.

The destruction of white working-class life

The authors’ description of the lives of America’s mid-century “blue collar aristocracy” would sound to today’s working-class whites like a vision of paradise lost:

The postwar labor market provided good jobs for those with only a high school diploma. Factory jobs, in steel works or auto plants, provided a good living, especially as people moved up the ladder. Men followed their fathers into unionized jobs, often with lifetime commitment from both workers and firm. Wages were high enough for a man to get married, to start a family and buy a house, and to enjoy the prospect of a life that was better in many ways than the life of his parents at the same age. [20]

America as a whole continues to get richer, with national income per capita growing by 85 percent between 1979 and 2017, but it would be an understatement to say that the white working class has not shared in this newfound wealth: White men without a four-year degree suffered a 13 percent absolute decline in purchasing power over the same period. It is others who have grown richer.

One measure of just how badly things have gone for the working class is that, while the American economy created nearly 16 million new jobs in the period 2010–2019, just fifty-five thousand were for people with only a high school degree. And the jobs available to those with limited schooling are not merely ill-paid; they:

do not bring the sense of pride that can come with being part of a successful enterprise, even in a low-ranked position. Cleaners, janitors, drivers, and customer-service representatives “belonged” when they were directly employed by a large company, but they do not “belong” when the large company outsources to a business-service firm that offers low wages and little prospect of promotion. [7]

More than half the people working at Google, for example, don’t work for the company; they work for cut-rate rent-a-worker services. Many perform the same jobs as actual employees, but they get no health- or retirement benefits. This system benefits Google’s stockholders.

Profs. Case and Deaton are to be commended for grasping, as some in their profession do not, that there is more involved in the economic erosion of a class than material loss:

Jobs are not just the source of money; they are the basis for the rituals, customs, and routines of working-class life. Destroy work and, in the end, working-class life cannot survive. Our account echoes the account of suicide by Emile Durkheim, the founder of sociology, of how suicide happens when society fails to provide some of its members with the framework within which they can live dignified and meaningful lives. [8]

The loss of meaning and self-respect that comes with the loss of family, faith, and community are what bring on despair, not just the loss of money, even though these non-material losses may be partly traceable to worse economic conditions. Marriage is part of the picture:

Throughout Western history, a man who wanted to live with a woman and have children had to be “marriageable.” This meant, among other things, that he could support his bride and had good future prospects. Once upon a time, grooms asked permission from the prospective bride’s father before asking for her hand, and the father’s obligation was to check that the groom was likely to be able to provide for his daughter. [167]

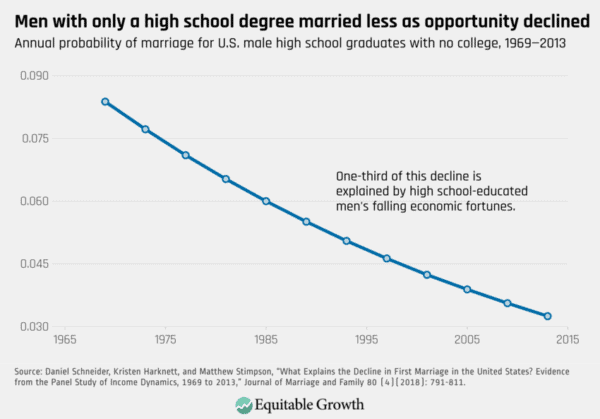

Today’s women may not rely on their fathers for this service, but as good jobs become scarcer and wages fall, the number of men women themselves view as marriageable has fallen:

In 1980, 82 percent of whites with and without a bachelor’s degree were married at age forty-five. By 1990, the rate had dropped to 75 percent for both. Beyond 1990, those with a bachelor’s degree maintained that rate, while that for forty-five-year-olds without a bachelor’s degree kept declining, to a low of 62 percent in 2018. [168-9]

Marriage has been replaced, at best, by serial cohabitation. This has been a disaster for children, “who tend to do much worse in fractured, fragile relationships than they would in intact families where both parents are present.” It has created a class of single mothers forced to work menial jobs to support their children and with little prospect of finding a better man the second time around. And the authors even manage to grasp that the sexual revolution has not transformed men’s lives into a succession of exciting sexual adventures:

[Men] have struck a Faustian bargain, promising at first, but with a high price to be paid in the end. By the time they reach middle age, they have no stable family with which they have shared lives and memories. They may have children from a series of relationships, some or none of whom they know and some of whom are living with other men [, but s]uch fractured and fragile relationships bring little daily joy or comfort. [172]

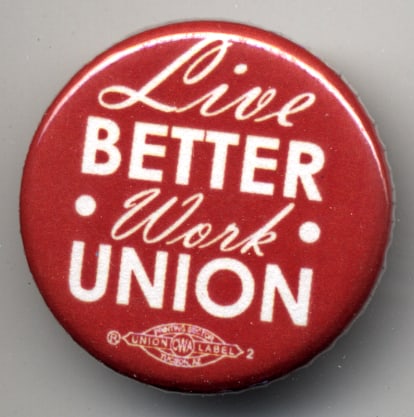

Today’s working-class whites are also less involved in their communities. For example, one form of social capital historically important in the lives of working Americans was trade unionism:

While not everything unions did was good, and while some of the benefits that they long argued for are now provided by employers as a matter of law, no one else in the workplace argues for the interests of workers as unions once did. Unions had a seat at the table when profits were being divided. They raised members’ wages (and, to a lesser extent, the wages of those not in unions), and they policed health and safety in the workplace. Unionized workers were less likely to quit and were often more productive. Unions brought some democratic control to workers, at work and more broadly, and were often a key part of local social life. [164]

At their peak in the mid-1950s, one third of American nonagricultural workers belonged to unions. Today, membership in private-sector unions has fallen to 6.2 percent. The numbers do not tell the whole story: “When I join a union, that is good not only for me but also for others; my joining strengthens the union, and thus brings benefits to other members.” This in turn makes the union even more attractive to outsiders, leading to a snowball effect and rapid growth. Unfortunately:

the process also works in reverse. Once people start leaving, not only does the union hall or the union sports team close, but the union loses some of its power to deliver benefits to its members, so there is less and less point in belonging. [175]

Church membership is another form of social capital that has been depleted. Before 1990, only 7 or 8 percent of Americans had no religious affiliation. By 2016, this had risen to nearly 25 percent, and the figure for young working-class whites was nearly 50 percent.

Regarding church attendance: In the late 1950s, nearly half of Americans could report that they had been to a place of worship in the past week. “There was a slow decline until 1980,” report the authors, “after which attendance held steady at around 40 percent until 2000, after which there was a steep plunge.” [176] The decline has been sharpest among the young and less educated. (Among Black Americans, church attendance is holding steady.)

The authors wryly remark: “We find it hard to believe that the spread of the internet and of social media has made up for the loss” of stable family life, unions, and churches.

The black precedent

Dilapidated row-homes in Baltimore (Credit Image: © Edwin Remsberg / VW Pics via ZUMA Wire)

The authors point out that the current problems of the white working-class were prefigured by those of urban blacks a generation ago:

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, African Americans in inner cities were employed in old-economy industries in manufacturing and transportation. With the beginnings of postwar foreign competition, the switch from manufacturing to services, and the evolution of cities from manufacturing to centers of administration and information processing, African Americans were hurt in the areas in which they had made the most progress. [67-68]

This is the process famously described by black sociologist William Julius Wilson in his 1987 book The Truly Disadvantaged. Most of the race’s talented tenth moved out of the inner cities, aided by recently passed laws against “housing discrimination.” This deprived urban black communities of their natural leaders:

Communities that had had a mix of professionals and manual workers, of more and less educated people, became increasingly deprived not only of successful and educated people but also of those in any kind of employment, with negative consequences for the community, and especially young men. [68]

For lack of marriageable (i.e., employed) men, black women started giving birth out of wedlock. Fatherlessness is, of course, a factor in many of the underclass pathologies we are familiar with. One such pathology was the crack cocaine epidemic of the 1980s, which:

shows both contrasts and parallels with the current [mostly white] opioid epidemic. Crack was cheap and offered an immediate high that was highly addictive. Crime rates increased, as those addicted looked for money for their next fix. As crack dealers fought for a place on the street corner, homicides among young black men spiked. While crack is still available and remains a scourge, the epidemic largely burned itself out by the mid-1990s. The aging of the population that had turned to crack as well as disgust among a younger generation that saw crack ruin the lives of family members and friends both appear to have played a role. [But] crack continues to cast a long shadow, having permanently increased the number of guns available in the inner city. [68–69]

The authors’ treatment of the parallels between today’s crisis of the white working class today and that of the black working class a generation ago is tantalizingly brief and (needless to say) uninformed by racial realism. It would bear deeper study.

Education, meritocracy, inequality

A crowd of college students at the 2007 Pittsburgh University Commencement. (Credit Image: Kit / Grads Absorb the News via Wikimedia)

As noted, the authors discovered early on that rising white mortality is heavily concentrated among those without college degrees. In part, this is because the economic value of the degrees has risen greatly:

In the late 1970s, those with a bachelor’s degree or more earned on average 40 percent more than workers who left school with a high school diploma. But by 2000, that “earnings premium,” as economists call it, had doubled, to an astronomical 80 percent. [50-51]

But the problem cannot be solved by having everybody go to college. Enrollment is already at a historical high, and since people have not been getting smarter, this has inevitably brought about a lowering of standards. As Joe Sobran once wrote: “In 100 years we have gone from teaching Latin and Greek in high school to teaching Remedial English in college.” But like too many others, Profs. Case and Deaton write as if Americans are getting more education simply because we are spending more years sitting in classrooms. They also leave entirely unmentioned the political corruption of education represented by the growth in “Resentment Studies” programs, although they do refer to increasing public distrust of higher ed. Whatever is protecting college graduates from deaths of despair, it is not the content of their coursework.

The authors point out that many occupations that previously did not require a college degree now do, but this is only in part due to rising demand for skills. In part, credentialism — the historically unprecedented stress now placed on degrees and certifications — is an inevitable by-product of the meritocratic ideal, which always requires some verifiable stand-in for such intangibles as “merit” or “ability.” Some of the consequent problems were anticipated by British sociologist Michael Young, who coined the term meritocracy back in 1958, and who predicted that such a regime would lead to disaster. Young’s principle concern was that:

the loss of the smartest children from the less educated group deprives them of talent that is useful to the group itself. Young writes that “the bargaining over the distribution of national expenditure is a battle of wits, and that defeat was bound to go to those who lost their clever children to the enemy.” He notes that the real reason the elites have been so relatively successful is that “the humble no longer have anyone — except themselves — to speak for them.” [54]

Could this explain the decline in unions and collective bargaining?

More recently, critics of meritocracy have noted the smug tendency of the elite to ascribe their success to their own virtues, when in fact they are simply those who won the genetic lottery for inherited abilities such as intelligence. Today, white elites’ very sense of identity hinges in part on their supposed moral superiority to their racial brethren, the bigoted rednecks who do not even know what “intersectionality” means.

Bill and Chelsea Clinton at their Chappaqua residence, where the average income is $229,000.

When meritocracy is first introduced, the new elite are more capable than the one they replaced, but like all elites they still try:

to entrench their own position. Being more able, they are more successful at the exclusionary and advantage-seeking strategies on behalf of themselves and their children that are privately enriching but socially destructive. When meritocracies are unequal, as is the case in the US today, with vast rewards for successfully identified merit, the rewards are also paid for cheating and for abandoning long-held ethical constraints that are seen as impediments to success. An unequal meritocracy is likely to be one in which standards of public behavior are low, and where some members of the elite are corrupt. An extreme case is the college entrance scandal of 2019, when wealthy parents paid bribes to secure places for their children at elite colleges. Our guess is that the rise of the meritocracy in today’s vastly unequal America has contributed to the “winner-take-all” and much harsher atmosphere in corporations today. [55]

In 1965, average CEO salary of America’s top 350 firms was 20 times the average worker’s salary; by 2018, the figure was 278 times. The authors note that the less successful for the most part do not object to inequality per se, but it is becoming hard for them to believe that elites are contributing anything to society in proportion to their fabulous rewards. Before the financial crisis:

many believed that the bankers knew what they were doing and that their salaries were being earned in the public interest. Afterward, when so many lost their jobs and their homes, and the bankers continued to be rewarded and were not held to account, American capitalism began to look more like a racket for redistributing upward than an engine of general prosperity. [12]

Michael Bloomberg, whose estimated net worth is 57.7 billion dollars. (Credit Image: The United Nations via Wikimedia)

Globalization and automation are often blamed for the deterioration of working-class life, but Profs. Case and Deaton point out that these factors affected plenty of other countries that have not had America’s dramatic shift of market and political power away from labor and toward capital. They point to two other factors. The first is oligopoly:

Consolidation in some American industries — hospitals, and airlines are just two of many examples — has brought an increase in market power in some product markets so that it is possible for firms to raise prices above what they would be in a freely competitive market. . . . [9] Policy bears much of the blame, particularly the failure to use antitrust to combat market power, in labor markets perhaps even more than goods markets . . . and to rein in rent-seeking by banks, doctors, hedge fund managers, owners of sports franchises, real estate businesspeople and car dealers. [11]

The second factor is political protection of business interests by politicians either beholden to corporate donors or unable to distinguish between the “free market” and the interests of the business class:

Analysis by political scientists of voting patterns in Congress . . . [show that] both Democratic and Republican lawmakers consistently vote for the interests of their more prosperous constituents with little attention to the interests of others. [13]

Specifically, the authors mention pharmaceutical companies successfully lobbying for patent extensions and questionable drug approvals, real estate dealers influencing tax laws in their own interest, and bankers helping rewrite bankruptcy laws in their favor and against the interests of borrowers: “lobbyists are well-placed to be the experts that legislators and their staffers turn to for information and analysis.” [210]

Immigration

Mass immigration is another important factor in the redistribution of wealth from labor to capital, because it lowers labor costs, but Profs. Case and Deaton’s treatment of this is the weakest part of their book. They do not so much as mention the subject until 80 percent of the way through, and their brief discussion begins with the following unpromising declarations: “Popular accounts of job loss often blame immigrants for stealing jobs. Populist politicians stoke people’s fears about immigration, not only in America but also in much of Europe.” [214]

Credit Image: © Esteban Biba / EFE via ZUMA Press

This is a near-perfect encapsulation of elite attitudes: Working-class whites want to restrict immigration because of irrational fear and hostility toward immigrants themselves. Public figures who want to limit immigration do not sincerely believe this will be good for their constituents; they are mere demagogues out for power (unlike, presumably, the advocates of open borders). The authors concede that “having more workers to compete with can certainly reduce wages, at least in principle,” but then conclude: “We judge that immigration did not play an important role in the long-term decline of the wages of less educated Americans.”

The American medical system

The author’s own surprising choice for the role of leading villain in their story is America’s health care system. They liken its costs to a tribute Americans must pay to a foreign power, specifically pointing out that the fraction of national income Weimar Germany paid in penalties under the Versailles Treaty was substantially smaller than what Americans unnecessarily spend on medicine today. In 2017, we devoted nearly 18 percent of GDP to medical expenses, equivalent to $10,739 for every man, woman and child, or about four times what we spend on national defense. The British spend less than 10 percent of GDP on healthcare, and about one-third as much for each person. The authors argue that “we could cut back costs by at least a third without compromising our health.” [192]

This excess “goes to hospitals, to doctors, to device manufacturers, and to drug manufacturers.” [202] American doctors get paid almost twice the average of those in other OECD countries. Drugs are about three times as expensive as in comparable Western countries. All this money has led to a large expansion of medical jobs: an additional 2.8 million between 2007 and 2017, which was a third of all new American jobs.

May 11, 2018 – President Trump announced a ”new blueprint” for lowering prescription drug prices. (Credit Image: © Ron Sachs / CNP via ZUMA Wire)

The authors admit that a free market lower prices, but doubt it would deliver better medicine because:

patients lack the information that providers possess, which puts us largely in their hands. We are in no position to resist provider-driven overprovision. [208] [Moreover,] during medical emergencies, people are not well positioned to make the informed choices on which competition depends. When someone is in distress, or perhaps even unconscious, there is no bargaining over rates, and no competition to restrain prices. In such conditions, you pay what you are asked. [200]

For example, ambulance service has been increasingly outsourced to private companies that understand medical emergencies are an ideal opportunity to ramp up prices. Outsourced ambulance services are often not covered by ordinary insurance, resulting in “surprise” medical bills. In rural areas, where hospitals are closing, air ambulance services are becoming more common, and they can bring surprise charges in the tens of thousands of dollars: “This sort of predation transfers money from people in distress to private equity firms and their investors.” [200]

Also, a medical system must have risk pooling, but this cannot be left to the market because:

[T]he healthier patients opt out of expensive insurance they do not need, leaving an ever sicker and ever more expensive group in the scheme. [Thus,] without compulsion to buy it, insurance cannot work. [208]

The authors point out that our current system is hardly an example of free market capitalism in any case:

The government is paying half of the costs, is paying the prices demanded by the pharmaceutical companies without negotiation (absurdly described as “market-based pricing”), is granting patents for devices and drugs, is permitting professional associations to restrict supply, and is subsidizing employer-provided healthcare through the tax system. [209]

There are other problems:

For a well-paid employee earning a salary of $150,000, the average family policy adds less than 10 percent to the cost of employing the worker; for a low-wage worker on half the median wage, it is 60 percent. This is one of the ways rising health costs turn good jobs into worse jobs and eliminate jobs altogether. [206]

The low-wage employee sees only that his employer pays for his medical insurance, not that its cost prevents his employer from hiring his out-of-work cousin.

Much of the money paid into the system goes for advertising and lobbying. The medical industry spends more on lobbying than anyone else; more than 10 times the total spent by organized labor:

In 2018, the healthcare industry employed 2,829 lobbyists, more than five for each member of Congress. More than half were “revolvers,” ex-Congress members or ex-staffers. We are certainly not claiming that healthcare gets to write its own rules. But there are no effective lobbyists arguing the case for the people who are paying for the enrichment of the healthcare industry or who can act as a countervailing power against it. [210]

The system’s lack of transparency, which encourages the illusion that someone else is paying for all of it, prevent more people from challenging it:

If at tax time, Americans got an annual bill for $10,739, or if employers showed their contributions to the cost of employees’ health insurance as deductions on workers’ paychecks, the political pressure for reform would surely be much stronger. [209]

Biased perceptions

The authors make a convincing case that the American medical system is a drag on the economy, and especially the more economically vulnerable working class. But the healthcare system cannot explain why white Americans specifically have been destroying themselves. Nor do the authors — despite the outrage they themselves provoked by presuming to write about whites at all — take any notice of the hostility increasingly directed at their own race. Could deaths of despair have something to do with American whites’ realization that “their” government sees them as obstacles to a happy rainbow future free of the oppression for which they are supposedly responsible?

The authors do note that:

According to a Pew survey, more than 50 percent of white working-class Americans believe discrimination against whites has become as big a problem as discrimination against blacks and other minorities. [166]

But they clearly disagree, and even uses the fashionable cant term, “white privilege,” a couple of times. They cite sociologist Andrew Cherlin:

[Whites] did not consider their status until their whiteness premium was lessened by legislation in the last few decades of the twentieth century. At that late date, the old, whiteness-based system had been in place so long as to be invisible to them, and the new equal opportunity laws seemed to white workers less like the removal of racial privilege and more like the imposition of reverse discrimination. [190]

This is conventional academic wisdom. Of course, one could speculate that anti-white bias is so entrenched in universities to the point that it has become invisible to academics, and that calls for dispossession now sound like devotion to justice and equality. It should not be surprising that, wearing such blinders, the authors are unable to understand why the weaker and more vulnerable members of a vilified nation might start losing hope.