Why Isn’t My Professor Black?

David Adams, American Renaissance, September 12, 2014

Subscribe to future audio versions of AmRen articles here.

“Why isn’t my professor black?” was the theme earlier this year of a panel organized by University College London (UCL), designed, it seems, to nourish a sense of grievance among black academics in Britain. The conclusion was predictable, because we’ve heard it all before–from the news media, from the Equality Commission, and from academics of every color: Insidious forms of racism persist in UK universities.

William Ackah, a black lecturer at Birkbeck, University of London, is quoted in Times Higher Education:

This [idea] that black life is . . . anti-intellectual still echoes down the corridors of time . . . Society has grown comfortable with black people in sport or music, [but] it has a problem with black people leading in public life and academia, even if . . . we are more than capable of doing so.

The Times goes on to note that “just 85 of the UK’s 18,500 professors are black,” and reports that, according to Dr Ackah, there are a lot more black academics, administrators and leaders in the United States, and not just in black studies. The Times adds that Shirley Anne Tate, a black sociologist at the University of Leeds, agrees that there is a “mindset that views black academics as ‘out of place.’ ”

How did these blacks discover this mindset? I have never come across it. Dr. Ackah might argue that this is because I am the wrong race, and therefore lack insight into such matters, but I would reply that, on the contrary, I am exactly the right race, since I could have encountered this mindset while talking to fellow whites outside the presence of blacks.

The “mindset” interpretation is echoed in a different article by Lucinda Newns, a part-time lecturer and doctoral student in post-colonial and diasporic literature–yes, there apparently is such a discipline–at London Metropolitan University. She reasons that the:

difference between the UK and the US has a lot to do with England’s colonial past and the central role that English literature played in shoring up ‘Englishness’ abroad, but it also has to do with the continuing perception in the UK that non-white populations are newcomers, making them seem like ‘add-ons’ to the established canon of ‘Great English Literature.’ And in times of austerity, such perceived ‘add-ons’ are always the first to be under threat.

This may be closer to the truth. The United States had a large black population from the beginning, whereas Britain began allowing blacks to settle only in the 1950s, and the majority came much later; immigration accelerated after 2000, under Tony Blair’s Labour government. Therefore, these non-white populations are newcomers, and the literature they have produced since, such as Sam Selvon’s novels, are add-ons. Comparing Britain and the United States is like comparing apples and oranges.

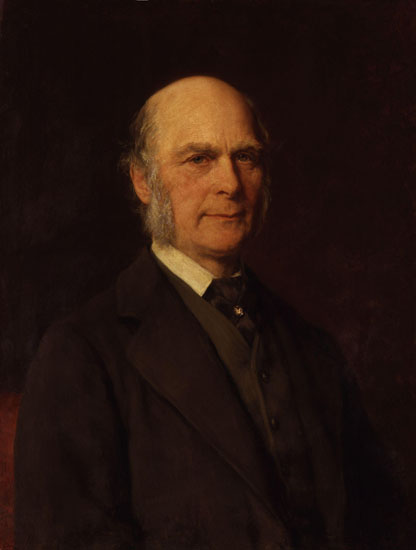

A bizarre point made during the UCL panel was that although the university holds anti-racist seminars, it continues to honor one of its benefactors, Sir Francis Galton, in the form of its Galton Lecture Theatre and the Galton Chair of Genetics (formerly eugenics), which he endowed. A black member of the audience asked, “Why do we celebrate someone like Francis Galton who hated us?”

Galton led an expedition in South West Africa (now Namibia) in the 1850s, and dealt with black Africans for several years. He certainly didn’t think highly of the Damaras, whom he found “intensely stupid” and “filthy and very troublesome in every way,” but this is not to say that he “hated” them.

Victorian explorers of Africa expressed varying opinions of the many and diverse tribes they encountered; some were favorable, some unfavorable. In his book, Narrative of an Explorer in Tropical South Africa (1853), which was feted for its accuracy and won both the Royal Geographical Society’s gold medal and the French Geographical Society’s silver medal, Galton had many good things to say about a different tribe, the Ovambo:

They are a kindhearted, cheerful people, and very domestic. I saw no pauperism in the country; everybody seemed well to do; and the few very old people that I saw were treated with particular respect and care. If Africa is to be civilized, I have no doubt that Ovambo-land will be an important point in the civilization of its southern parts. (p. 229)

He also added that the Ovambo “have a high notion of morality in many points, and seem to be a very inquiring race.” (230)

Of their women, he said:

The ladies were buxom lasses . . . They were decidedly nice-looking; their faces were open and merry . . . They seemed to be of amazingly affectionate dispositions, for they always stood in groups with their arms round each other’s necks like Canova’s graces. (213)

Galton described the chief of the Ghou Damup, as “a gentleman, and very courteous,” who “had a charming daughter, the greatest belle among the blacks that I had ever seen, and a most thorough-paced coquette.” (104)

Returning to the UCL panel, at events of this type a foreordained conclusion determines the topic. The question, “Why isn’t my professor black?” could have been challenged with “Must he be?” but this would never occur to the organizers, because of their assumption that inequality is always the result of prejudice. There may be other factors–blacks may not have the same cultural and social attitudes–but it seems more attractive to play the blame game. Surely, this is because it is the strategy most likely to yield something for nothing, in the form of unearned access, promotions, and privileges.

Noteworthy also is the fixation on blacks. When it comes to race, it’s almost always about blacks. Whites talk about of diversity, but even outside the United States, it’s always the first black whatever who gets the most publicity. Blackness is a symbol of virtue, a moral fetish.

In her account of the UCL event, our lecturer in post-colonial studies Miss Newns reflects on her lack of blackness:

I’ve recently attended a number of events on similar topics . . . . I share in the anger at the under-representation of non-white voices and experiences within UK academia.

However, they also brought to the fore an uneasiness that has been with me since the beginning of my doctoral studies, when I was asked to assist on some undergraduate modules as part of the now sadly closed Caribbean studies degree at London Metropolitan University. Its students at the time were primarily black and tended to have links–either through birth or family background–to the Caribbean, neither of which I could claim. The lecturer (who was black and Caribbean) kept reassuring me that I knew more than the students, but I couldn’t shake the feeling that personal experience would invariably trump academic knowledge when it came to questions of race.

It is often said that ‘impostor syndrome’ is a common experience among PhD students, but does my whiteness make me an impostor in some academic spaces for reasons beyond my novice status?

Thankfully, she adds that her “partner, who is not white, has joked that I should bring him along to academic events as a way to increase my ‘street cred.’ ”

This joke has astonishing implications. A white British person, living in Britain, attending a British university, feels like an impostor–an alien who doesn’t belong in her academic discipline.

This certainly has to do with the very conception of “post-colonial” studies. If colonial literature told the story of colonization from the point of view of the colonizers, post-colonial literature is–and was from the beginning–supposed to tell the story of colonization and its aftermath from the point of view of the colonized. Since academia is dominated by the Left and far Left, it is not only the voices of non-whites, but also the voices of all groups perceived as oppressed that are privileged. And “privileged” is the correct word; such people are much more important than the former colonizers; in fact, the latter are not to be included at all, unless they are diffident, apologetic, and guilt-ridden, like Miss Newns.

How does Miss Newns’ confession fit into the “mindset” of black exclusion the UCL panel was denouncing? First, university payrolls are limited, so hiring a black professor means leaving a white one unemployed. Second, white voices are as much a part of the post-colonial experience as non-white ones. Whites have been deeply affected by large transfers of populations from former colonies to formerly homogeneous homelands, yet “post-colonial” studies are designed to crowd out and even silence those voices.

If Miss Newns feels like an impostor, why not step aside and let a black woman take her place? She worries that:

there is the possibility that my appointment to a permanent academic post (should I be lucky enough to obtain one) could be a result of the very hegemonic structures that my work and politics purport to resist.

Fortunately, she:

can take some comfort in arguments such as those put forward by the post-colonial feminist scholar Trinh T. Minh-ha, who asserts that ‘the understanding of difference is a shared responsibility, which requires a minimum willingness to reach out to the unknown’–in other words, that resisting racial hierarchies should not be the job of only those who experience racism.

So there is hope, even for a white who wants take part in the post-colonial conversation. Her only authorized role, however, is as a racial expiator and redeemer, and to take an active role in her own displacement and erasure.