Into Darkest Africa

David Adams, American Renaissance, March 14, 2014

Subscribe to future audio versions of AmRen articles here.

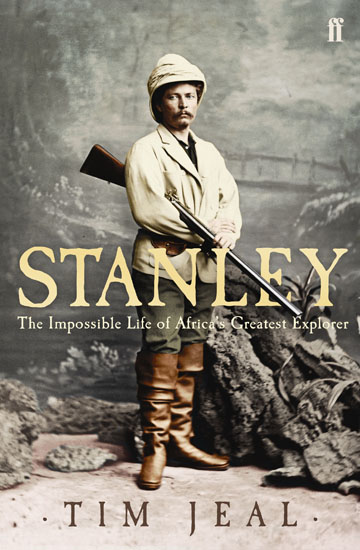

Tim Jeal, Stanley: The Impossible Life of Africa’s Greatest Explorer, Faber and Faber, 2007, 570 pp, £25.00.

Along with Richard Burton, John Speke, Samuel Baker, and David Livingstone, Henry Morton Stanley was one of the greatest Victorian explorers of Africa. He was the youngest of this group, and it was he who finally assembled the scattered and uncertain knowledge of central Africa into a coherent geography. He explored the great lakes of the region and the sources of the Nile, was the first to trace the Congo river from the continent’s interior all the way to the sea, and helped open Africa for trade with Europe.

Stanley’s reputation was controversial even in his lifetime, and 1990s biographies by Frank McLynn and John Bierman savaged him. He was accused — and still is — of brutality, casual killing, and duping 300 Congo tribal chiefs into handing over their land. He was portrayed as an accomplice of Leopold II’s ruthless exploitation of the Congo, was blamed for abuses committed by some of his officers in the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition, and was described as motivated by a “volcanic rage against the world.” Some even claimed he was a closet homosexual with a sham marriage. In short, Stanley came to be seen as embodying the worst aspects of the Victorian era and European imperialism.

It turns out that scholars have erred. His descendants made Stanley’s personal papers inaccessible until 2002, and they tell a different story. This major biography by Tim Jeal, the first to benefit from access to these papers, is a welcome correction. The Stanley he uncovers is different both from those of earlier biographies, and from that of Stanley’s own puffed-up accounts of his expeditions.

This is not a hagiography. Mr. Jeal acknowledges both great virtues and great faults, but he puts put these in context, thereby illuminating Stanley’s actions and motivations, which Mr. Jeal traces to his grim early life.

Henry Morton Stanley was born John Rowlands, in Denbigh, North Wales, on January 18th, 1841. He was the illegitimate child of an unknown father — legend has it that it was James Vaughan Horne, a Denbigh solicitor — and a promiscuous mother, Elizabeth Parry, who would later marry and run two public houses. Elizabeth was unwilling to look after him — though she had cared for an older illegitimate son — and John fell to his putative grandfather, John Rowlands, Jr., a local farmer. He died when John was five, and the boy’s uncles decided to pay a poor local family to look after him. They later stopped paying for his upkeep — perhaps hoping the family had grown fond enough to keep him — but the family sent the boy, then eight, to the St Asaph Workhouse.

Victorian workhouses were harsh and loveless places, more brutal even than Charles Dickens’s depiction in Oliver Twist, published some ten years earlier. They were a last resort that attached the stigma of ignoble origins to all who ended up in them. Two years after coming to the workhouse, John managed to escape to his uncle’s house, but, after a happy afternoon under his aunt’s care, was ordered back to St Asaph the following morning.

John finally left the workhouse in 1856 at age 15, and was kept by a cousin on his mother’s side, Moses Owen, a school headmaster who tutored him in mathematics and literature. Owen’s mother, however, thought that her son’s marriage prospects would be spoilt by “harbouring his feckless aunt’s bastard son.” John was first sent to labor on a farm but was then turned over to yet another uncle, this one in Liverpool. This man had been reduced to manual labor, however, and could not keep the young man, who, after a period of tramping, found work as a butcher.

One day, when he was delivering meat to an American packet ship, the captain offered him five dollars a month and a new outfit if he would sign on as cabin boy. This was not a genuine offer: Boys like him received beastly treatment at sea, with the expectation that they would desert at the first port of call, allowing the captain to pocket their wages. John fell into this trap and left the ship in New Orleans seven weeks later.

In America, John began a process of reinvention in an effort to distance himself from his painful early life. He called himself Henry Stanley, later claiming he took the name in honor of a wealthy American businessman who had adopted him. He maintained this fiction to the end of his life, even though he later came under public scrutiny and his mother — who suddenly developed an interest in her son after he became famous — was talking carelessly to the press. On his last trip to America, he even scoured New Orleans graveyards looking for an heirless Henry Stanley he could claim was his stepfather.

When the Civil War broke out, Stanley enlisted in the Confederate Army but was captured at the Battle of Shiloh. He had a choice of prison or enlistment in the Union Army, and spent time in an army hospital. However, he had friends in the South, did not want to fight the Confederacy, and decided to desert. In 1864, Stanley then enlisted in the US Navy, serving as record keeper aboard the Minnesota. He was able to start a career as a freelance journalist, but after seven months he again deserted, in hope of finding adventure.

Stanley had long been fascinated by David Livingstone’s Missionary Travels. After the war, he and a friend scraped together a little money from various jobs to fund an expedition to the Ottoman Empire. In Turkey, they were beaten, robbed of everything they had, and one member of their group was raped at knifepoint. There was a trial, during which Stanley managed to win the group’s freedom and even restitution for stolen equipment.

In 1867, Colonel Samuel Forster Tappan recruited Stanley to report on the work of the Indian Peace Commission, a body established by the US government to make peace with the Plains Indians. Stanley’s vivid prose was well received, and he was not long after hired as a foreign correspondent by James Gordon Bennett, proprietor and founder of the New York Herald.

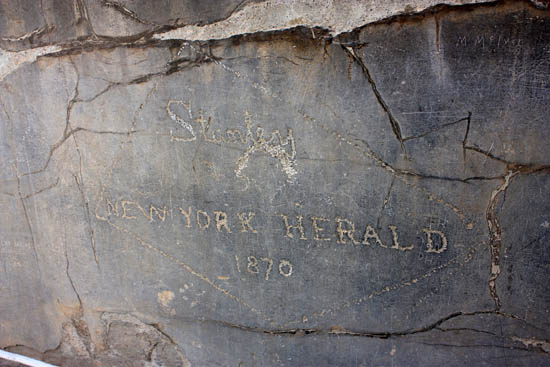

It was as a reporter for the Herald that Stanley undertook the expedition to find David Livingstone. The famous missionary was known to have been in the Congo since 1866, but little had been heard from him, and at one point he had been presumed dead. In his first book, How I Found Livingstone, Stanley claimed that the New York Herald’s Bennett instructed him to go on the expedition and offered him unlimited funds for this purpose. In fact, it was Stanley’s idea. He had to lobby for it, and the funding was adequate but not munificent. Stanley tried to impress readers by inflating the figures, as he would do in other books.

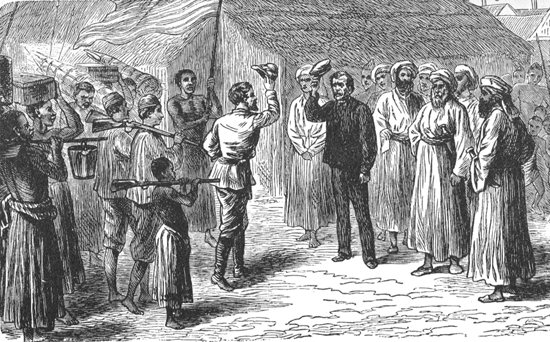

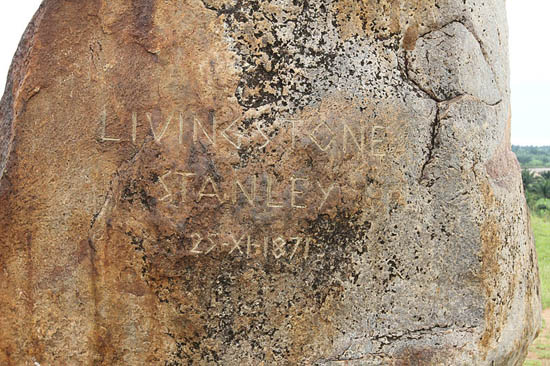

Stanley’s 700-mile expedition was, however, genuinely heroic. During his eight-month journey, he caught malaria; was caught up in a local war; fought starvation, theft, and desertions; and had to negotiate swamps, deserts, jungle, and many tribes — some hostile. On November 10, 1871, Stanley found Livingstone in the town of Ujiji, now part of Tanzania, but Stanley’s description of their meeting is fiction. He never said “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” He invented the phrase later to sound dignified, but even Victorians ridiculed it as pompous.

Livingstone had been described to Stanley as an irascible misanthrope, and Stanley spent the entire journey worrying that the older explorer would get wind of the attempt to find him, and move off to another region. In fact, Livingstone was amiable, generous, and unpretentious. He had been a legend in Stanley’s eyes, and Mr. Jeal writes that the relationship between the two became like that of father and son.

The two spent four months together exploring the region, and Stanley would always remain loyal to the missionary’s memory, a friend to his family, and champion of his mission to end the slave trade in equatorial Africa and civilize the natives with Christianity. It was his experience with the older man that inspired Stanley to become an explorer. The Livingstone expedition made Stanley famous, but he also made enemies by criticizing the British consul at Zanzibar for not properly supplying Livingstone.

In 1874, Stanley was commissioned by the New York Herald, along with the Daily Telegraph, to solve the geographical puzzles Livingstone had left unsolved. This was a successful — though horrific — expedition that lasted 999 days, and cost 114 lives; Stanley was the only white man to survive. The expedition established the geography of the lake region and traced the Congo all the way to the sea.

Stanley’s book on the trip, Through the Dark Continent, included an account of a conflict in which a number of natives were killed at Bumbireh. Stanley’s enemies in the British establishment later used the account to treat him as a monster and even launch a formal inquiry. The controversy resulted partly from exaggeration — Stanley’s desire to cater to a bloodthirsty audience and to cultivate a public persona as the hard man of the jungle — but it prompted much pontificating in the press by self-righteous arm-chair adventurers.

The controversy helped sell Stanley’s book, but also gave him a reputation for brutality. This left him with only one possible sponsor for his next Africa expedition: King Leopold II of Belgium.

Stanley had by this time been witness to the evils of the central African slave trade, and hoped his work for the Belgian king would help eradicate it. Stanley’s books and Mr. Jeal’s biography clearly show that the slave trade in the African interior was run not by Europeans but by Arab-Swahili traders, with the cooperation of various African kingdoms. Arabs had been in Africa since the 9th century, and by the early 1870s were operating at least as far as Unyanyembe in modern Tanzania. Many of the tribes Stanley encountered had never seen Europeans, but were well acquainted with the Arabs, who also ran a hugely profitable ivory trade.

In his Congo River expedition, Stanley had seen villages razed and depopulated by slave raids, and tribes broken by the theft or sale of their relatives. Like Livingstone, he wanted to do “something wonderful” for the Congo. He and many others thought the way to break the slave trade was to open Africa to the world, which would provide industrialized nations with raw materials and new markets. It would also destroy the market for slaves, since by trading with Europe, Africans would be able to buy goods they wanted — typically cloth, beads, and brass wire — without selling each other.

Leopold, on the other hand, wanted a colony, and was interested in the Congo because of its natural riches. Leopold played on Stanley’s idealism, and presented the project of building trading stations along the Congo River as a philanthropic mission. Ostensibly, the idea was to improve conditions in the region through Christianity and civilization, but what Leopold sought was a legal basis to acquire a personal fiefdom.

Stanley was to sign treaties with local chiefs to obtain the rights to build the stations on their land. He sought merely tenancy agreements, whereas Leopold wanted outright sovereignty. Mr. Jeal tells us that the treaties Stanley signed with the chiefs were later destroyed and replaced by new ones, granting sovereignty in legal language contrived to fool the illiterate chiefs. Mr. Jeal also reports that Leopold had editorial control over Stanley’s book on the expedition, and that the treaty printed in The Congo and the Founding of its Free State was one of the latter ones — not a treaty Stanley did or would have signed.

Thus, it was Stanley who was duped by Leopold, not the chiefs duped by Stanley. Stanley was later angered by the reported abuses of Belgian officials in the Congo Free State, but Mr. Jeal thinks Stanley was unwilling to believe the extent of the treachery, and rationalized the deception as perhaps necessary in order to achieve humanitarian goals.

Stanley’s last expedition, the Emin Pasha relief effort, also damaged his reputation. The aim was to rescue Emin Pasha (Eduard Schnitzer), a Jewish German doctor from Silesia who had been named governor of Equatoria, an Egyptian province in the extreme south of the Sudan. When the Mahdists captured Khartoum in 1885 and killed General Charles Gordon, the Anglo-Egyptian administration of the Sudan collapsed, leaving Equatoria cut off.

The British public came to see the pasha as a second General Gordon, and there was widespread support for a rescue mission. Ordinarily, Stanley chose his expedition members personally. He generally preferred black men, having found whites too attached to their luxuries and prone to complain. The only whites he ever chose were tough men with backgrounds like his own. On this occasion, however, the expedition was organized by William Mackinnon, a Scottish philanthropist and businessman with experience in colonial ventures, who raised money for the effort. The key personnel came mostly from the gentleman and officer classes. Stanley was still working for Leopold, however, so a compromise was needed in order for the king to let him go: Stanley would take a longer route along the Congo River to secure more land, but the king would provide Free State steamers for transportation.

The Emin Pasha relief expedition was perhaps even more difficult than Stanley’s earlier efforts. After his party survived extreme danger, disease, famine, and hostile (sometimes cannibal) tribes, it turned out that of the promised steamers, only one was in full working order, and they were insufficient to carry the men and equipment to Equatoria. Stanley decided to split the expedition into a Rear Column, which would remain encamped at Yambuya, and an Advance Column, which he would lead in an attempt to reach Emin Pasha. The two columns were to rejoin later.

After immense difficulties, particularly in the nearly impenetrable Ituri forest, where the men were attacked by pygmies with poison arrows, Stanley reached his objective, though it was an anti-climax. Emin Pasha had misrepresented the situation entirely, and, far from being a man fighting the enemy bravely against incredible odds, he was barely in command. He was happy to get supplies, but was reluctant to be relieved, and returned to the coast only after much indecision.

The Rear Column, meanwhile, had fallen worryingly silent. Returning to the site 16 months later, Stanley discovered a single European in charge of what remained of the camp. The majority of the porters had died of starvation or disease; bodies lay unburied; filth was everywhere, and the survivors were sickly skeletons. Stanley was able to reconstruct events and learned that Edmund Barttelot, the officer he had left in charge, had completely lost his mind a year earlier, gone on a rampage of brutality, and been shot in a dispute. Also, the big-game hunter James Sligo Jameson had apparently bought a young female slave, given her to cannibals, and sketched the scene as she was slaughtered and eaten.

Upon returning to civilization, Stanley had the difficult task of explaining this debacle. Mr. Jeal argues that in his book about the expedition, In Darkest Africa, Stanley muted his criticism of Barttelot and Jameson since he, as the leader, would have been blamed for staffing the expedition with moral idiots. All the same, Barttelot’s and Jameson’s families attacked Stanley for defaming the men. Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness was reportedly inspired by the principal figures of the Rear Column.

Critics also contrasted Stanley with Emin Pasha, who they made out to be a benevolent scholar. This, too, was distortion: The pasha condoned brutality to the extent that even the Manyama cannibals would not sell slaves to him. Again, Stanley was damned if he told the truth, damned if he didn’t. He would bear on his conscience for the rest of his life the 500 lives lost on a pointless expedition.

Stanley’s return to London marked the beginning of the final period in his life. The artist Dorothy Tennant set her cap for him, and they were married in 1890. He loved her deeply but in time found himself harried by her possessiveness, her interest in politics, and their different natures. Perhaps most frustrating was Dorothy’s insistence that he run for office.

Mr. Jeal explains that because Stanley was denied a proper home life as a child he did not want to disrupt his marriage by opposing his much younger and strong-willed wife. He therefore let himself be drafted into running for a seat in Parliament in 1892 as a Liberal Unionist. Stanley detested politics and found the process of canvassing for votes utterly demeaning. He therefore refused to campaign, in the secret hope of losing. He did manage to lose his first election but was elected in 1895, and became MP for Lambeth North. He held this post until 1900, and was relieved when his “sentence” was finally over.

By the 1890s, Stanley was only in his 50s but in poor health; the ravages of his expeditions made him look 15 years older. He bought a mansion in Pirbright, Surrey, where he found peace away from his wife, and in the company of an adopted son, Denzil, who came from his Welsh relatives. He had no children of his own.

Stanley died in 1904. Although he had been knighted in 1899, he was denied burial next to Livingstone at Westminster Abbey because he remained controversial. He was buried instead at St Michael’s Church, in Pirbright. The granite gravestone bears the inscription, “Henry Morton Stanley, Bula Matari, 1841 – 1904, Africa.” “Bula Matari,” a nickname he acquired in Africa, means “breaker of rocks” in the Kongo language. His wife called him by that name and it appears on the statue of Stanley unveiled in 2011 in front of the public library in Denbigh, Wales, where he was born.

Mr. Jeal writes in his afterword that when Dorothy edited Stanley’s unfinished autobiography — written to perpetuate the fictions about his early life — she tried to protect his memory by issuing denials, misdirecting the press, and restricting access to his personal papers. Denzil continued this practice.

Clearly, Mr. Jeal means to rehabilitate the great explorer, and believes that for Stanley the truth is the best defense. He cultivated a tough exterior; but we learn that he was charming, amiable, and easy-going when he was able to relax in private. His rough-hewn persona was a necessary consequence of his early life, in an era that was more aggressively masculine than our post-feminist times.

What of his reputation for brutality? He dealt forcefully with deserters, thieves, and liars, and there were many on his expeditions. However, he tried to avoid conflict with the tribes he encountered by offering them gifts and friendship. When he used deadly force it was when he faced an imminent threat to life. It is true that he was an instrument of Leopold’s ignoble designs, but he was not a knowing instrument. Besides the Faustian urge of his race, his motives while in the king’s employ were largely humanitarian, and he believed the king’s were as well.

In How I Found Livingstone, Stanley writes that as he was making his way back to the East Coast toward towards the end of the expedition, he was shocked to learn that slavers were already using the routes he had pioneered. Once they realized someone had found a way they exploited it.

There was more tragedy: The desire to break the slave trade and to civilize peoples who might have been better off left alone led to the horrors of the Congo Free State, and the Emin Pasha expedition introduced deadly new diseases to the area. The road to hell was truly paved with good intentions. Mr. Jeal nevertheless offers historical context and a dose of realism to the question of post-colonial guilt:

The Victorians were hooked on needing to feel virtuous and, in our own way, we are too. With the benefit of hindsight, we know that colonialism had some disastrous consequences . . . . So we virtuously condemn those who did not see these things coming many decades before they actually came to pass. And yet we forget that between the late 1880s and 1910s, the various colonial administrations brought to an end large-scale enslavement of Africans; and subsequently, in British and French territories at least, maintained over much of the continent relatively incorrupt government under the rule of law. We also fail to ask ourselves what would have happened if the Arab-Swahili had remained unopposed throughout Africa. Darfur provides a clue.

Mr. Jeal also raises the question of whether equatorial Africa really needed European-style civilization:

Men like Mackinnon and Stanley believed in the moral worth of the new industrial society, having seen for themselves the outlawing of child labour, the advent of compulsory state education, and the way in which an increase in national wealth had brought prosperity to far more people than had once seemed possible. They had not seen European nations fight two bloody world wars, nor dreamed of anything so terrible as the gas chambers, or the dropping of the atom bomb, nor suspected that technological advances might one day threaten the planet. . . . Stanley . . . believed he was bringing numerous advantages to the Africans. So European intervention in Africa seemed wholly desirable.

Natives often expressed admiration at the superiority of the white man, and Stanley felt the need to comport himself with the dignity of someone representing his race. In How I Found Livingstone, he writes of the Manyara people who had never encountered Europeans, but who had dealt with Arabs. They marveled at Stanley’s appearance, clothing, and equipment. After a morning with the chief and his men, the chief said at parting, “Oh . . . these white men know everything, the Arabs are dirt compared to them!”

Not surprisingly, Jeal’s Stanley met with opposition from predictable sources: The London Review of Books published a scathing review, while a Professor Makau Mutua reviewed it for Human Rights Quarterly under the title, “An Apology for a Pathological Brute.” This did not prevent accolades: winner of the 2007 National Book Critics Circle Award for biography; named one of the 100 Notable Books of 2007 by the New York Times Book Review; silver medal winner of the 2008 Independent Publisher Book Award for biography, and many other awards. Even the notoriously left-leaning Guardian published a fair and open-minded review.

Perhaps there is hope for a reassessment of the colonial period.