Written by a European for Europeans

Jared Taylor, American Renaissance, April 26, 2022

Dominique Venner was a French historian, essayist, and activist who, on May 21, 2013, took his own life – in the Cathedral of Notre Dame — in protest against the degradation of the West. In the suicide note he left on the altar, Venner wrote:

In the evening of my life, facing immense dangers to my French and European homeland, I feel the duty to act as long as I still have strength. I believe it necessary to sacrifice myself to break the lethargy that plagues us. . . . I chose a highly symbolic place, the Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris, which I respect and admire: she was built by the genius of my ancestors on the site of cults still more ancient, recalling our immemorial origins.

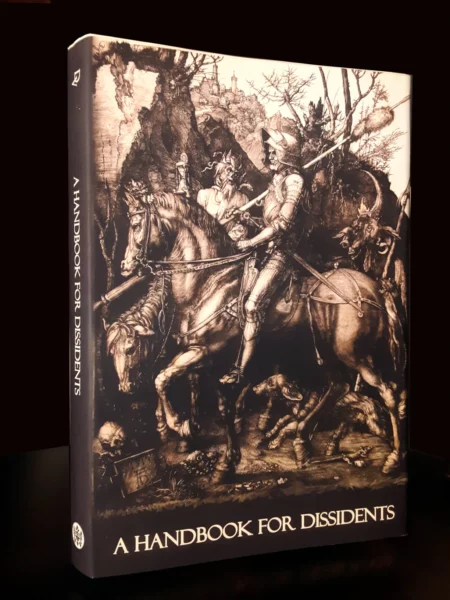

Several of his books are now available in English. His most recent, A Handbook for Dissidents, has just been made available in a lovingly illustrated edition available here. I was honored to be asked to write the foreword.

“This Handbook was written by a European for Europeans,” writes the French patriot and essayist Dominique Venner. “Others, coming from other peoples, other cultures, other civilizations, will be able to read it, of course, but only out of intellectual curiosity.” A handbook is a guide or a set of instructions, and this is a guide to meeting the greatest threat Europeans have ever faced: “The Great Replacement” — the process of demographic substitution named by another great Frenchman, Renaud Camus.

Venner calles it “unlike anything ever seen in the past.” This is because, unlike the potentially mortal threats Europeans met at Marathon in 490 BC, at Tours in 732, and before the gates of Vienna in 1683, The Great Replacement is something we permit. Venner writes: “If this monstrous enterprise . . . can be carried out, it is because of the connivance of twisted or decadent elites, but also and above all because Europeans, unlike other peoples, have lost their identitarian memory, their awareness of what they are.”

Venner is confident that his people will rise and save their civilization, but he warns that “there are no political solutions outlined in this volume, but a different view of the world and of life.” This book is therefore a challenge – a challenge to today’s Europeans to be worthy of their past and to build a future of which their ancestors would be proud. I believe this book was also a challenge to Venner himself, a reminder of the standards by which a true European lives and – in Venner’s case, especially – the standards by which he dies.

Venner says he writes for Europeans, but he also writes mainly for men, because we have let male and female fall out of balance:

The masculine alone would yield a world of brutality and death. The feminine alone is our world: fathers have disappeared, and children have become spoiled, weak, and tyrannical little monsters; criminals are not guilty, but victims of society or sick people that we must nurse. . . . [U]nder the cloak of advancing women, feminism has spread hostility to manhood and debasement of femininity . . . . To speak, as we sometimes do, of a “feminization” of our societies seems inappropriate to me. The real issue is emasculation.

Venner even writes, “[T]he presence of war, even if only as a shadow, is what gives a society its meaning and poetry. This is what allows it to coalesce and maintain itself as something more than a shapeless mob—a people, a city, a nation.”

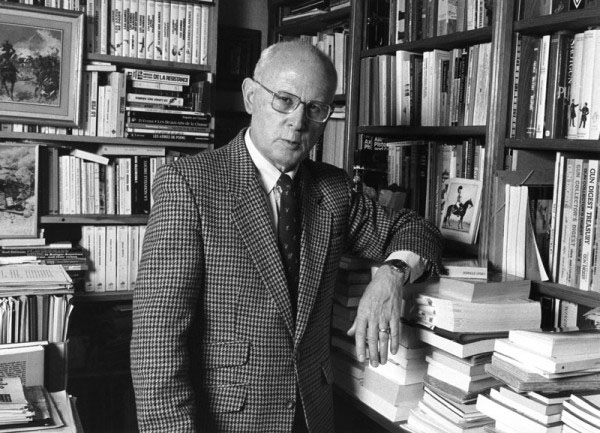

Dominique Venner

Today’s Europeans fight absurd wars meant to turn all people into interchangeable consumers of pointless goods and ideological fetishes. Venner explains why:

The belief in our universal calling is wrong and dangerous. It imprisons Westerners in a paradoxical ethnocentrism that prevents them from recognizing that other men do not feel, do not think, and do not live like them . . . .

Venner adds: “Men live only by what distinguishes them: clans, peoples, nations, cultures, and civilizations—not by what they have superficially in common. Common humanity is mere animality.”

Anyone who understands this and raises his voice against capitulation finds himself at war with his own people. Venner writes that he:

discovered that the courage required of a radical dissident in a time of civil war dwarfs that of the heroes of regular wars. The latter receive from society legitimacy and attestations of glory. On the contrary, the radical dissident must find within himself his justification, and face covert repression as well as the blame and hate of the masses.

Anyone who fights for Europe today knows this.

How do we rediscover who we are? For Venner, the answer is in Homer, for The Iliad and The Odyssey are not just the founding stories of our civilization; they are scripture. Homer reveals “the core of European civilization:”

Who am I? What are we? Where are we going? To these questions, Homer has given us ever-valid answers, and he is the only one to do so with such depth. To the Europeans who question themselves and their identity, his two great poems offer a mirror in which to find our own true inner face, stoic courage in the face of the inevitable, the fascination for what is noble and beautiful, the contempt for baseness and ugliness. . . .

For Homer, life, this small, ephemeral and so common a thing, has no value in itself. It becomes worth something only because of its intensity, its beauty, and the breath of greatness that everyone can give it—above all in his own eyes.

Although most of Homer’s heroes are men, Penelope is likewise a paragon of strong, faithful, admirable womanhood.

“Odysseus and Penelope” by Johann H.W. Tischbein, 1802.

In a just a few words about Homer, Venner describes everything that today’s European is not: “[Homer] awakens in us a thirst for heroism and beauty. . . . To the Europeans, the founding poet reminds that they were not born yesterday. He hands down to them the kernel of their identity, the first perfect expression of an ethic and aesthetic heritage of tragic courage in the face of an inescapable destiny.” Homer also stresses “the importance for an individual to feel a vital sense of belonging to a people or a city that precedes him and will outlive him.”

Venner also admired the Stoics who believed that “everything that does not depend on our freedom of action (e.g. accidents, illness, sometimes even wealth or poverty) is neither good nor bad in itself; it is indifferent. We must then stop worrying about it.” Venner paraphrases Epictetus: “People, things can kill me, not affect me in my soul, because I have made it invulnerable, inviolable.”

Venner cites a passage from one of André Maurois’ novels about young British officers Maurois met during the First World War:

Their youth served to thicken their skin and harden their heart. They fear neither fist nor fate. They consider exaggeration as the worst of vices, and coldness as a sign of aristocracy. When they are despondent, they wear the mask of humor. When they are ecstatic, they say nothing not all . . . .

Venner adds, “Unable to control fate, they were taught to control themselves.”

We cannot read some passages in Samurai of the West without thinking of Venner’s own tragic-heroic end. He writes that it was the Romans “who turned suicide into the philosophical act par excellence, a human privilege denied to the gods” who can never die. Venner also admired the Japanese warrior ethos.

Altar of Notre Dame Cathedral. (Credit Image: Nmillarbc, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

“Seppuku [a warrior’s ritual suicide] was not just a means of escaping dishonor for the bushi [warrior],” he writes. “It was also an extreme way of demonstrating their authenticity with a free, heroic act.” He quotes from the 18th century guide to the warrior, the Hagakure: “It is necessary to prepare for death all day long, and day after day,” adding in his own words, “Thus we will outgrow the angst of living and the fear of dying. . . . Only if we are subjected to it is death meaningless. If it is willed, it has the meaning we give it, even when it has no practical use.”

In a milder passage, Venner writes: “Death brings an end to cruel diseases and the decay of old age, thus giving way to the new generations. Death can also prove to be a liberation when one’s fate becomes too painful or dishonorable.”

For Venner, Christianity has become an obstacle to European heroism. He quotes Celine:

Spread among the virile races—the hated Aryan races—the religion of “Peter and Paul” performed its duty admirably: it reduced the subjugated peoples to poor and submissive sub-humans, starting from the cradle; it sent out these hordes, confused and stultified, drunk with Christ-literature, on quests for the Holy Shroud and magical hosts; it made them forsake forever their blood-gods, their race-gods . . . . Here is the sad truth: Aryans never knew how to love or worship but other peoples’ god, never had their own religion, a white religion . . . .

Venner also quotes Jean Raspail, author of The Camp of the Saints: “[Immigrants] are protected by Christian charity. In a way, Christian charity is leading us to disaster!”

But if Venner is an atheist, he is a respectful, Christian atheist: “I do not scratch out the Christian centuries at all. Chartres Cathedral is as much a part of my world as is Stonehenge or the Parthenon. This is the inheritance we must receive.” He also writes that “It is not necessary to be a Christian to enter [a church] . . . . Calm, silence, and architectural beauty make a church a beneficial retreat. . . . Sit apart, and let the silence enter you.”

But Christians must change:

I hope that in the future, from my village church as well as our cathedrals, we will continue to hear the reassuring chime of bells. But even more I hope that the prayers heard under their vaults will change. I hope that people stop begging for forgiveness and mercy, and ask instead for vigor, dignity, and energy.

It was, of course, in one of the most famous churches of Christendom that Venner took his own life.

Dominique Venner believed that so long as European man does not go extinct, his degenerate outward forms can be brought back into conformity with his ancient, indomitable spirit. He bought this book to a close with words for us to live by:

Whatever you do, your priority must be to cultivate within yourself, every day, like an augury of good fortune, an indestructible faith in the permanence of the European Tradition. . . .

We know that individually we are mortal, but that the spirit of our spirit is imperishable, as is that of all great peoples and all great civilizations. When will the great awakening occur? I do not know, but of this awakening I have no doubt.