May 2005

| American Renaissance magazine | |

|---|---|

| Vol. 16, No. 5 | May 2005 |

| CONTENTS |

|---|

California Prison Segregation to End

The Lucasville Riot

Hurrah, Hurrah, for Southern Rights, Hurrah!

The Crime the Media Chose to Ignore

O Tempora, O Mores!

Letters from Readers

| COVER STORY |

|---|

California Prison Segregation to End

The Supreme Court ignores racial reality.

On February 23, the United States Supreme Court issued a ruling that is likely to stamp out the last vestige of government-enforced racial segregation in the United States. In Johnson v. California, it ordered the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals to review the housing policies of the California prison system, and to apply legal standards that will probably lead it to ban the practice of temporarily grouping new arrivals by race and ethnicity. At issue was whether the California Department of Correction’s (CDC) decades-old practice of giving prisoners initial cellmates of their own race violates the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. The policy, of course, was to keep inmates from killing each other, but merely saving lives is less important to six Supreme Court justices than promoting the myth that race is not supposed to matter.

Prison Reality

The California prison system is not only the largest in the country but also the most racially mixed. Of 160,000 inmates, men account for 150,000 or 94 percent. In 2003, the system took in more than 112,000 men. The racial mix is an almost perfect recipe for friction: 37 percent Hispanic, 29 percent white, 29 percent black, and six percent Asian, American Indian, and Pacific Islander. Race- and even ethnic-based gang violence is the top security concern for prison guards. California, in the words of one official, is “ground-zero” for race-based prison gangs.

For prisoners in most states, aside from the fact of incarceration itself, race is the central reality of life. For California prisoners, race-based gangs are often the very key to survival. Gangs protect members from other gangs, and are a source of information on friends and enemies. Gangs supply food and cigarettes, and arrange visits from people on the outside. Gangs dictate prison etiquette, and enforce it with violence. Because prison is such a dangerous place — a single misstep can provoke a beating or even death — gang members form strong bonds.

There are two main Hispanic prison gangs in California: the Mexican Mafia or La Eme (from the Spanish pronunciation of the letter “m”), which is a southern California Hispanic gang, and Nuestra Familia, a northern California Hispanic gang. The northern and southern Hispanics hate each other. Nuestra Familia has a sub-group, Nuestra Raza, that operates in the high-security housing units. The main black prison gang is the Black Guerilla Family, although the Crips and the Bloods are also active. There are two major white gangs, the Aryan Brotherhood and the Nazi Low Riders. The Low Riders grew out of the Aryan Brotherhood in the 1980s and tend to be younger. The Hells Angels have a minor presence.

Interestingly, the Aryan Brotherhood has a defensive alliance with the southern Hispanics of the Mexican Mafia against the northern Hispanics of Nuestra Familia and against the Black Guerilla Family. Apparently southern Hispanics hate their northern kinfolk even more than they hate white people. The Aryan Brotherhood also has friendly relations with the other white gangs, the Nazi Low Riders and the Hells Angels.

Gangs are inherently violent. They routinely rob other prisoners or force them into prostitution. Some gangs make prospective members kill another prisoner in order to join. This is known as “making your bones.” Hispanic and black gangs are notorious for mayhem but the Aryan Brotherhood is no stranger to violence, either. Prison authorities describe it as “a singularly vicious prison gang that has a hostility to black inmates.” Race-based gangs are such a problem in California that the state built a special “Supermax” prison at Pelican Bay — in the northwest corner of the state, as far from other prisons as possible — to hold the worst cases. This is where the leaders live.

Gangs are the only significant prisoner groupings, which means there are no real affiliations that are not race-based. Race and ethnicity are the boundaries of what amount to warring armies. This is why California temporarily separates new male inmates by race. Women are less violent, so they are never segregated.

Housing prisoners is complicated. There are 32 prisons in the state, but only seven have what are euphemistically known as “reception centers” that process newcomers and transfers. There is segregation only in the reception centers, and a new convict never stays in a center for more than 60 days before he is assigned permanent quarters. These are either attached to the reception center or in a prison that doesn’t have a center. Whenever a man transfers from one prison to another, he makes a stop of no more than 14 days in a center before he gets his new assignment.

There is great variety in prison housing, with many men double- and triple-bunked in great, barracks-like rooms that hold as many as 225. In “reception centers,” however, prisoners get two-man cells, where they are evaluated to see what kind of permanent housing (general population, maximum security, etc.) they should get. These two-man, reception-center cells where men are held for brief evaluation are never integrated. Most men probably don’t even know there is a segregation policy; they get a cellmate of the same race and think nothing of it.

What is the purpose of the evaluation? First, the authorities have to decide how violent a prisoner is likely to be. They consider his physical and mental health. They check his criminal history, and if he is transferring from another prison, they read his prison record. Low-security men — the most numerous — go to dormitories. Medium-security men get permanent two-man cells, and maximum-security threats get single cells. If a man is known to have testified against another prisoner, to have shot someone’s best friend, or to have some other reason to hate or be hated, this affects his housing assignment. Convicted police officers and child molesters — whom all other prisoners despise — get special treatment, too. The prison system tries to be very thorough in its evaluations, and has a 75-man unit that does background checks both inside and outside the walls.

The men in centers are therefore new additions to a population, and guards want to look them over before deciding what to do with them. They are probably complete strangers to each other, sharing living quarters that are more cramped and intimate than anything most of us will ever experience, and prison authorities want cellmates to get along. Size and physical condition are part of the calculation, since no one wants to put a weakling in with a gorilla. The idea is to give a man a cellmate he is unlikely to hate — someone of his own race.

In many cases, officials even subdivide prisoners along ethnic lines. “You cannot house a Japanese inmate with a Chinese inmate. You cannot,” says Linda L. Schulteis, Associate Warden at California State Prison-Lancaster. “They will kill each other. They won’t even tell you about it. They will just do it,” She says the same is true for Laotians, Vietnamese, Cambodians, and Filipinos. Likewise, a Hispanic from northern California cannot be put in the same cell with a Hispanic from southern California. “They already have a conflict before they come to prison,” explains prison spokesman Margot Bach, “and it’s going to intensify when they come to prison.”

No other part of the California prison system is segregated, not the recreational facilities, dining halls, work areas or job assignments. Nor are dormitories reserved for certain races, though the authorities make sure they are racially balanced to reduce tension. If a prison is 50 percent Hispanic, 30 percent black and 20 percent white, dormitories should reflect those proportions. If there are just a few prisoners of one race in a dormitory dominated by another there is likely to be trouble. But even in mixed dorms, no prisoner is ever assigned a bunk directly over a prisoner of another race. Fights have broken out when this happened.

What about the two-man cells for medium-risk offenders? In order to increase compatibility and reduce violence, the system lets inmates choose their own permanent cellmates. Both men sign forms saying they want to share a cell, and authorities grant the request unless there are security reasons not to. Needless to say, no one can think of a case in which someone asked for a roommate of another race. Miss Bach of the prison system says, “there is peer pressure when you get to prison to align with a [racial] group for protection.” Charles Hughes, a corrections lieutenant at the Lancaster prison is blunter: “If a black inmate asked for a white celly [cellmate] there is no way in hell that I would do that. I’d refer them both for a mental-health evaluation.”

Given the extraordinary level of racial tension in California prisons, guards would clearly like to segregate the entire system. Initial segregation, before authorities have a sense of whom they are dealing with, appears to be the minimum of common sense, and the California system stands behind it. Prisoners never willingly share a two-man cell with someone of another race. The system wisely refrains from forcing them to do so.

What is the origin of the challenge to the practice? Garrison Johnson, who filed the original complaint, is a career criminal and former Crip, who was convicted in 1987 of murder, robbery and assault, and sentenced to 25 years to life. Mr. Johnson has been transferred five times, and at each stop along the way he got a black cellmate. In 1995, Mr. Garrison filed a pro se (meaning he represented himself) complaint with the Central District of California against the prison system, arguing that always being paired with a black violated his 14th Amendment rights to equal protection. After several years of procedural give-and-take, including appeals, in 2000 the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco instructed the district court to assign Mr. Johnson a lawyer and hear the case. When the district court upheld the segregation policy, he appealed to the Ninth Circuit, which, in 2003, also upheld the policy. That was when he took the case to the Supreme Court.

Since Mr. Johnson is a violent, medium-security prisoner, he lives in a two-man cell. This means he gets to choose his celly — and he has always asked for a black. He says he simply could not ask for a white: “You can’t cross races. That will start racial tension right there. So I know I can’t go to a white guy and say, ‘Hey, I want to move with you’ because he is not going to move with me.”

Mr. Johnson’s reasoning for challenging the system is the following: Racial tension in prisons is so bad it is impossible for him to make friends with anyone who is not black. Blacks would turn on him if he tried, and non-blacks would spurn him. This, he says, puts in him danger whenever there is racial violence, because he does not have a single friend of another race to stick up for him in a riot. If, however, he spent 14 days with a white cellmate when he was transferred, he might make a bosom friend who would protect him the next time blacks and whites are fighting. Mr. Johnson has 25 years to life to make white friends. In effect, he is saying he wants the prison system to make friends for him.

The Ninth Circuit Ruling

Like so many court cases, Johnson v. California has a complex but interesting legal background. The equal protection clause, on which Mr. Johnson hung his case, has generally been interpreted to require that government pretend race does not exist. In Shaw v. Hunt in 1996 (which challenged the creation of two largely black North Carolina congressional districts), the Supreme Court wrote, “Racial classifications are antithetical to the Fourteenth Amendment, whose central purpose was to eliminate racial discrimination emanating from official sources in the States.” The Court has established a standard of “strict scrutiny” when it comes to race (or religion, national origin, and sometimes sex), meaning a government agency must have a very compelling reason to take any notice of race at all.

The Supreme Court did not formally end prison segregation until the 1968 case of Lee v. Washington, when it ruled that Alabama could no longer segregate cellblocks. The court did note that “prison authorities have the right, acting in good faith and in particularized circumstances, to take into account racial tensions in maintaining security, discipline, and good order in prisons and jails,” but never offered guidelines for when racial classification was legitimate. Several lower courts have cited Lee to argue that “unsubstantiated” fears of racial violence do not justify segregation. These courts have usually limited racial separation to lockdowns following race riots or other violence.

In 1987, however, the Supreme Court ruled in Turner v. Safley that prison administrators may limit constitutional rights of inmates if limiting those rights serves a “legitimate penological interest.” Turner had nothing to do with race — the question was whether prisoners could write letters and get married — but the Court held that the standard of “legitimate penological interest” applied to all constitutional claims, which would include equal protection. The justices wisely pointed out that “courts are ill equipped to deal with the increasingly urgent problems of prison administration and reform,” and that “the problems of prisons in America are complex and intractable, and, more to the point, they are not readily susceptible of resolution by decree.”

In Turner, the Supreme Court established four rules for deciding whether a prison policy that limits inmate rights meets the standard of “legitimate penological interest.” The first is whether there is a “valid, rational connection” between the policy and the goal it is supposed to achieve. The second is whether there are “alternative means” by which prisoners can exercise the rights they lost because of the policy. The third is how much trouble it will make for a prison if inmates exercise their rights, and the fourth is whether there are any “ready alternatives” to the policy in question.

Mr. Johnson’s lawyers argued that segregation did not meet the Turner standard because there was no rational connection between temporary segregation and preventing violence. They claimed — amazingly — that since California prisons could not point to a single act of violence that had been caused by integrating two-man cells, the system’s reasons for segregation were “unsubstantiated fears” of racial violence and therefore unconstitutional. Of course, there have been no such acts of violence because two-man cells are never integrated.

The Ninth Circuit found a clear Turner standard connection between the segregation policy and its objective of reducing racial violence. It noted that one of the worst prison riots in US history was triggered in large part by the forced integration of cells (see next article). “Under Johnson’s view,” it added, “the same violence would have to occur within the CDC [California Department of Corrections] in order to permit race to be considered as a factor in making initial housing decisions. We disagree . . . The CDC simply does not have to wait until inmates or guards are murdered specifically because race is not considered in assigning an inmate’s initial cell mate; instead, Turner allows the administrators to stave off potentially dangerous policies without first ‘seeing what happens.’” In other words, California was under no obligation to integrate prison cells just to see if its decades-old segregation policy really was preventing murder.

The Ninth Circuit also refuted Mr. Johnson’s argument that the policy of temporary segregation increased racial animosity by perpetuating racial stereotypes. It pointed out there was already plenty of racial tension in prisons with or without segregation, and that it was silly to argue that a measure designed to keep violence down was actually increasing it. Mixing up the races in cells would probably lead to more racial violence, not interracial friendship. The court also went to great pains to point out just how pervasive racial tension is in California prisons. It listed case after case in which racial gangs attacked each other, and noted that some prisons have been kept locked down for years at a stretch because race riots would erupt if there was the slightest contact.

At the end of this grisly recitation, the court noted dryly, “In short, this is hardly a case where the prison administrators are acting on an unsubstantiated record.” Therefore, “administrators are well within their discretion to attempt to rectify or to reduce further violence by taking reasonable measures.”

The second Turner test is whether there are “alternate means” for a prisoner to exercise his rights, that is, whether blacks and whites have other opportunities to get acquainted despite the segregation policy in the reception centers. The Ninth Circuit found this was obviously true, since the same-race cell assignment never lasted more than 60 days. Mr. Johnson can meet all the whites he wants in the dining hall or the recreation yard.

The third Turner standard, whether granting prisoners constitutional rights would make a lot of trouble for the prison authorities, was met by testimony from prison officials. Then-California prison system director Steven Cambra told the court, “If race were to be disregarded entirely . . . there will be problems within the individual cells. These will be problems that the staff will have a difficult time controlling. I believe there will be fights in the cells and the problems will emanate onto the prison yards . . . [I]t would be very difficult to assist inmates if the staff were needed in several places at one time.” In other words, there would be fights in the cells, violence would spill into the rest of the prison, and the guards would be overwhelmed.

As for the fourth Turner standard, whether there was a simple alternative to segregation, it was the responsibility of Mr. Johnson, as plaintiff, to offer one. His solution? Ask prisoners if they have ever been in a racial gang or if they don’t like people of other races. The Ninth Circuit called this “disingenuous,” adding, “There is little chance that inmates will be forthcoming about their past violent episodes or criminal gang activity so as to provide an accurate and dependable picture of the inmate.” That, of course, is why the system has a staff of 75 investigators — prisoners lie.

The Ninth Circuit therefore concluded that the 14th Amendment permits temporary segregation. Because of the special circumstances of prisons, this form of racial classification need meet only the looser standards of Turner and not the “strict scrutiny” standard that prevails elsewhere. Mr. Johnson did not accept this ruling and appealed to the US Supreme Court.

Before the Supreme Court

By this time, of course, Mr. Johnson had a hot, court-appointed lawyer, a prominent litigator named Bert H. Deixler with the nationally-known firm of Proskauer Rose. Mr. Deixler argued that the Ninth Circuit was wrong to apply the Turner standard and that by doing so, the lower court had “carved out a wholesale ‘prison exception’” when it came to race. He repeatedly invoked the Supreme Court’s ruling in the University of Michigan affirmative action cases, Gratz and Grutter (see “What the Supreme Court Did,” AR, August 2003), pointing out that “all nine Justices were in agreement that strict scrutiny applies whenever the government classifies based on race” and arguing that this should be the standard everywhere and without exception.

Mr. Deixler bought Mr. Johnson’s claim that even brief segregation fed dangerous racial stereotypes, and proposed that the best way to undermine the influence of race-based gangs in prison was to integrate two-man cells. Justice John Paul Stevens, one of the Court’s most liberal members, was especially pleased by this silly argument.

Mr. Johnson found an ally in the Bush administration, which sent the acting solicitor general, Paul D. Clement, to argue that given the country’s “pernicious history of race” — from which prisons are not exempt — it is vital that all racial classifications be subject to strict scrutiny. Otherwise, he implied, the innate racism of prison administrators would take over.

During oral arguments, the justices seemed most concerned that the segregation policy applied to prisoner transfers as well as newcomers, wondering why they needed to be segregated when they had already been under prison system control, and had already been evaluated. The response of California senior assistant attorney general Frances T. Grunder was weak. She said it was often hard to get a prisoner’s records transferred at the same time as the prisoner. Justice David Souter wondered if instead of segregating transfer prisoners, the system should just send the papers more quickly. Miss Grunder could have made a different argument: No one already in the prison system ever asks for a roommate of a different race, so the system should not court trouble by forcibly integrating two-man cells.

The segregation policy also seems to have suffered because of its success. The justices wanted to know if there had ever been racial violence because people of different races were put in a reception cell. No, there hadn’t, because the cells are never integrated. Rather than see this as proof the policy works, some justices seemed to think it showed the prison system’s fears were exaggerated.

The Decision

In its February ruling, Justices Breyer, Ginsburg, Kennedy and Souter joined Sandra Day O’Connor in sending the case back to the Ninth Circuit where the segregation policy will be subject to “strict scrutiny.” In her view, any consideration of race by government is “immediately suspect” and must clearly promote a “compelling state interest.” Any lower standard will fail to “ferret out invidious uses of race.” Justice O’Connor also fell for Mr. Johnson’s claim that segregation — even for as few as 14 days — may increase interracial violence by “perpetuating the notion that race matters most.”

Justice John Paul Stevens issued a dissent, but only to insist that the housing policy was unconstitutional on 14th Amendment grounds and did not need any further “strict scrutiny” review. He wants the cells integrated right away.

Chief Justice Rehnquist was sick with thyroid cancer during the case, and did not participate. Justice Clarence Thomas issued a real dissent, in which Justice Scalia joined.

Justice Thomas pointed out that the case required the Court to choose between two conflicting lines of precedent. On the one hand, the Court has stated that all racial classifications by government must be subject to strict scrutiny. At the same time, the Court has said the Turner standard applies every time a prison policy limits a prisoner’s constitutional rights.

Which precedent should the Court choose? To Justice Thomas, decisions about race and violence “are better left in the first instance to the officials who run our nation’s prisons.” He accused his colleagues of indifference to the reality of prison life, writing, “The majority is concerned with sparing inmates the indignity and stigma of racial discrimination. California is concerned with their safety and saving their lives.” Justice Thomas even wrote that he thought temporary segregation might survive “strict scrutiny.” Keeping Americans from killing each other is surely a “compelling state interest.” If the Ninth Circuit decides it is not, the California prison system will start mixing up the two-man cells. Mr. Johnson’s white celly might turn out to be a 200-pound Skinhead who has always wanted to strangle a black man in his sleep. As Justice Thomas put it, somewhat more delicately, Mr. Johnson, “who concedes that California’s prisons are racially violent places, and that he lives in fear of being attacked because of his race . . . may well have won a Pyrrhic victory.”

In fact, it is whites who will suffer most from forced integration. Blacks and Hispanics have a well-documented history of raping whites, especially the young and the weak. For many convicts, night after night of uninterrupted sodomy with a terrified white cellmate would be a dream come true (for a discussion of prison rape, see “Hard Time,” AR, April 2002).

Whites who have served time know how much race matters. Joshua Englehart is a white man who served 37 months in San Quentin on drug charges. He wrote in the Los Angles Times that prisoners will pay the price for this foolish decision “because the truth is that mixing races and ethnic groups in cells would be extremely dangerous for inmates.” “[P]rison is an undeniably racist place, and court rulings aren’t going to stop it,” he explained. “Rule No. 1: The various races and ethnic groups stick together.” Mr. Engelhart concluded that segregation “is looked on by no one — of any race — as oppressive or as a way of promoting racism. It is done for their own safety, and they know it . . . This ruling will strike dread in the hearts of all California inmates when they read about it.”

This Supreme Court decision is a particularly dangerous example of how our nation lets ideology blind it to reality. That Sandra O’Connor and five other justices of the Supreme Court of the United States could actually think that briefly separating blacks from whites from Hispanics during evaluation adds to racial tensions in prison simply beggars belief. Can they really believe convicts show up without strong racial feelings, notice they got a same-race roommate in the reception center, and then decide the races are not supposed to get along? These six justices — who hold more power than even the President — have a completely fantasy-land view of what race means, either in prison or in the country at large. This is the view that guides them and our other rulers when they make important decisions that affect our very survival as a nation and a people.

| ARTICLE |

|---|

The Lucasville Riot

Integration and its discontents.

The Southern Ohio Correctional Facility is a maximum-security prison in Lucasville, about 80 miles south of Columbus. In the words of one Ohio supreme court justice, it gets “the worst of the worst.” On April 11, 1993 — Easter Sunday — prisoners rioted and took control of L Block (one of the three main cellblocks) taking a dozen guards hostage. They beat all of them severely, and quickly released four they were afraid would die. During the 11-day siege that followed, they murdered nine inmates and a guard, making it the longest and third-most deadly prison riot is US history.

Although the spark that started the riot was a plan to inoculate black Muslim inmates with a TB vaccine containing alcohol, which they say violated their religion, racial hatred played a major role. At the time of the riot, the prison was under a court order to integrate double cells, and a new warden named Arthur Tate, a black man, appears to have enforced the order with blind enthusiasm. In just a few months, the number of integrated double cells went from 1.7 percent to 31 percent. Inmates complained that men were not allowed to choose their cellies, and that random assignments put known racial enemies in the same cell. They said the warden told them that the only way they could refuse integration was to attack their new cellmates. In one case, a member of the Aryan Brotherhood told the warden that if he “put a nigger” in his cell, he would kill him. Guards ignored him and gave him a black celly. The white convict immediately smashed him in the face with a padlock wrapped in a sock.

Some people thought Mr. Tate was trying to provoke a riot, presumably to support his campaign to have the prison upgraded to an even higher security rating. White prisoners, a minority, thought Mr. Tate and his chief deputy, also black, were discriminating against them.

Three main gangs operated in the prison — the Black Muslims, the Black Gangster Disciples, and the Aryan Brotherhood. The Black Muslims started the riot by attacking the guards, and during the first few hours of chaos, prisoners settled scores, most of them racial. At a dangerous point in the riot Keith Lamar, a black man not in either black gang, found his path blocked by Black Muslims. He promised that if they let him pass he would kill white “snitches,” and the Muslims agreed. He then organized a “death squad” to find and kill whites whom he accused of cooperating with prison authorities. His group murdered four men, including one who was 69 years old and used a walker. He also forced one white prisoner to beat another white to death.

After the initial confusion, any man who could sought protection from one of the gangs, each of which controlled a section of L Block. The leader of the Black Muslims, Carlos Sanders, was afraid there would be race war when the Aryan Brotherhood started taking revenge for Mr. Lamar’s killings, and proposed a truce to its two leaders, George Skatzes and Jason Robb. The men agreed that henceforth, only whites would kill whites, and only blacks would kill blacks. The whites appear to have kept their word. Mr. Skatzes of the brotherhood had already killed one white informer, and he and Mr. Robb killed another before the riot ended. However, Mr. Sanders was later accused of ordering the death of a white inmate who had allegedly raped a black prisoner. The Gangster Disciples also agreed to the truce, and for the remainder of the siege, the gangs managed an uneasy coexistence.

Not all prisoners rioted. Some escaped to other parts of the prison and turned themselves over to authorities. The ones who could not escape were traitors in the eyes of the rioters. The gang leaders rounded them up and kept them in cells under gang “security.” After the initial violence, whites managed whites, and blacks managed blacks.

The gang leaders negotiated with prison authorities, and even broadcast their demands on local radio and television. One of their chief demands was an end to the policy of integrating double cells, but they also wanted less crowding, and the removal of the warden and his deputy. In order to convince authorities they were serious, the gang leaders agreed to murder one of the eight guards they were still holding. They chose Robert Vallandingham, a 40-year-old white man. It isn’t known who actually killed Mr. Vallandingham, but inmates have testified that Anthony Lavelle, leader of the Black Gangster Disciples, strangled him.

As food ran out and conditions worsened, the prisoners lost their bravado. On April 21, 1993, they surrendered peacefully. More than 50 inmates faced charges in connection with the riot, and Black Muslim leaders Carlos Sanders and James Were, Aryan Brotherhood leaders Jason Robb and George Skatzes all got the death penalty for killing Officer Vallandingham. Anthony Lavelle, who may actually have killed the guard, testified against the others in exchange for a lighter sentence. Keith Lamar, who organized the anti-white hit-squads, was also sentenced to death. As of publication date, no one has been executed. Arthur Tate, the warden whom all the prisoners hated, continued his career in prison administration.

In the end, the Lucasville riot did solve the integration problem in maximum-security prisons in Ohio. All men now get single cells.

| BOOK REVIEW |

|---|

Hurrah, Hurrah, for Southern Rights, Hurrah!

The League of the South’s roadmap to secession.

Michael Hill (Editor), The Grey Book: Blueprint for Southern Independence, Traveller Press, 2004, 170 pp., $20.00.

More than eight decades ago, the Irish poet William Butler Yeats wrote the now-famous lines, “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold.” That the center of the American Empire cannot hold has at no time been more evident than now, with the current wave of secessionist movements rising up across the country: the Alaskan Independence Party, the California Secessionist Party, the Hawaiian Sovereignty Movement, the New England Confederation Movement, the North Star Republic, the Cascadian National Party, the Aztlan movement, the Republic of Texas, and the Green Mountain Republic of Vermont.

And then there’s Dixie. In 1994, 27 Southern patriots organized the League of the South (then known as The Southern League) around the time-honored principle of Southern independence. Ten years later, their manifesto for a new nation is here, in The Grey Book: Blueprint for Southern Independence.

Why secession? As The Grey Book explains:

“Since the War for Southern Independence, the South has been redefined by an alien and revolutionary vision radiating from Washington, DC: the American Empire. It has imposed on its once-free citizens a vast and oppressive bureaucracy in the form of welfare and affirmative action programs that squander our wealth and incite racial strife . . . It has assumed control over the education of our children, who are taught little except to hate their ancestors and to despise their own people. It has, while pursuing empire abroad, refused to defend its own people against an epidemic of crime, the invasion of our borders by illegal aliens, and the international agencies that are bit by bit chipping away at the sovereignty of these United States.”

Reform is impossible, according to the League, for these and a dozen other reasons neatly outlined in chapter three. The League understands that because the South is the most “culturally distinct” region of the US, it is often at odds with the rest of the country. For example, representatives of the South voted against the Immigration Reform Acts of 1965 and 1986, both of which passed nonetheless, with disastrous consequences.

The League defends the principle of secession by reminding readers that the United States came into being because the American colonies seceded from England. Furthermore, the League contends that because the US Constitution does not expressly forbid states from seceding from the union, the right of secession is reserved to the people of the states, in accordance with the Tenth Amendment.

A new Confederation of Southern States (CSS) composed of the 11 states of the original Confederate States (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia) would be home to 80 million people and trail only the remaining United States and Japan in gross domestic product. This new CSS would be based on the foundation of family, faith, and community under a limited and decentralized government. Beyond protecting its borders and its people, the CSS would leave governance to its sovereign states.

“But is it realistic?” members of the League are always asked. Yes, they say. According to a Southern Focus Poll conducted annually by the Odum Institute in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, a full 12 percent of Southerners say they would favor Southern independence if it could be achieved by peaceful means. Another seven percent are not sure. The League asserts that the American Revolution began with not much more support from the colonists (it estimates about one in six colonists were in favor of secession.)

Even so, the League acknowledges that secession it not an immediately practical goal and that the first step toward an independent Dixie is to create a mass base of like-minded Southerners. To this end, members urge cultural secession or “abjuration of the realm.” Culture, according to the League, is the essential organizing principle of a nation, and they reject the Democratic/Republican argument that America is a proposition nation. Rather, the League maintains that a shared culture is “the only legitimate, long-lasting foundation for genuine peace, for genuine order, and genuine, shared prosperity.”

Without a culture, the people perish, and without its core Anglo-Celtic population, the culture of the historic South will be lost. The League understands that Southern heritage and values are under attack by institutions of both the Left and the neoconservative Right, and it points out that the government, the media, and academia are waging a culturally genocidal war against the descendants of the great civilizations of Europe. The League argues that America’s historic population being replaced with “more compliant Third-World peoples” who are accustomed to the kind of government “now being put in place on the ruins of the constitutional, limited government established by the Founders.”

In response, the League promises to act on the following ten points:

- “Advance the interests and independence of the Southern people.

- “Defend the historic Christian faith of the South.

- “Educate Southerners (and other Americans of good will) about our history and our civilisation.

- “Protect the symbols and heritage of the traditional South.

- “Maintain our link with the great civilisations of Europe, especially that of the Anglo-Celts, from which the South has drawn its inspiration.

- “Encourage the development of healthy local communities and institutions by seceding from the mindless materialism and vulgarity of contemporary American society.

- “Restore the traditional rights reserved to the States under the Constitution.

- “Form friendships and alliances with sympathetic movements striving for devolution of government and independence for authentic nations and regions, both inside and outside of these United States.

- “Stimulate the economic vitality and self-sufficiency of the Southern people.

- “Pledge our lives, fortunes, and sacred honour to the cause we have undertaken.” (The Grey Book, like the League’s other publications, uses British spelling.)

The authors of this book are what American Renaissance would call racial realists; therefore, they reject the “flawed Jacobin notion” of egalitarianism that underlies America’s current public policy. They would eliminate affirmative action as well as all attempts to “remake society in their image of diversity” and that serve “profiteers with endless streams” of cheap labor:

Though the Left will claim this as evidence of our ‘racism,’ to allow non-Western peoples and their institutions to dominate the South would destroy our civilization as we know it.

At the same time, the League “disavows a spirit of malice” towards Southern blacks and welcomes their cooperation “in areas where we can work together as Christians to make life better for all people in the South.”

Much of this 170-page book is an outline of policies for a new Southern nation. Of particular interest are discussions of immigration and race relations, which are worth quoting at length. On immigration, the League states:

The strength of a country is continuity from the past to the future. Consequently, the CSS immigration policy shall not bring radical changes to an area or its people. Southern immigration policy will limit overall numbers of immigrants to prevent burgeoning population growth and attendant problems of overcrowding, excessive urban and suburban development, and environmental stress. Southern immigration policy also will not permit extensive change of the South’s cultural, ethnic and socio-economic make-up. Change of this sort is not conducive to true good will and tolerance, but rather to mistrust and division which unscrupulous interests will exploit.

‘Immigrants wishing to become citizens of the CSS would be required to reside in one of its states for at least a decade.’ They would need to renounce ‘all loyalty to their countries of origin’ and obtain character references from leaders of their communities. Mastery of the English language would be required of them as would extensive knowledge of Southern history and civics. The League states unequivocally, ‘Citizenship will not be granted to the children of foreign parents simply because they are born in the CSS.’

Illegal immigration would not be tolerated. Borders would be well patrolled, and law enforcement officers at all levels would have authority to arrest and deport illegal aliens.

On race relations, the League acknowledges that “historically the interests of Southern blacks and whites have been in part antagonistic.” As a Christian nation, the CSS would look to Scripture for guidance. Blacks would be treated as “brothers in Christ” and would be afforded the same constitutional protections as other law-abiding citizens:

[The government] shall leave the races alone to work out their problems in private spheres (e.g. between individuals, families, churches, businesses, etc.) Race relations, especially between whites and blacks in the South, have been poisoned by the interference of various agencies of the federal government and by the cultural scourge of ‘political correctness.’ To remedy this problem, government shall have no place in favouring or handicapping one racial group in relation to another. All shall be free to pursue their own interests under the law.

That being said, the League makes clear that its first duty is to self-preservation. “White Christian Southerners are the blood descendants of the men and women who settled this country and gave us the blessings of freedom and prosperity. To give away this inheritance in the name of ‘equality’ or ‘fairness’ would be unconscionable.”

The CSS would eliminate welfare, in accordance with Second Thessalonians 3:10: “if any would not work, neither should he eat.” Voluntary organizations would attend to those truly in need, whatever their race. “Though many blacks may be taught to hate us in their homes and institutions,” the League cautions, “our response to them must be grounded in Christian charity.”

The Grey Book ends with two appendices. The first is a collection of “snapshots” by various unidentified authors on the growth and development of the League. Although interesting, these short essays are largely restated material covered earlier in the book. The second appendix answers questions most frequently asked about the League, and is a quick overview of the League’s philosophy, goals, and plan for secession.

Southern secession is not the Confederate flag-waving delusion its critics would have us believe. Authors as diverse as Gore Vidal (The Decline and Fall of the American Empire), Robert D. Kaplan (The Coming Anarchy), Thomas W. Chittum (Civil War Two: The Coming Breakup of America), and Michael Hart (in The Real American Dilemma) have warned that secession, partition, or actual civil war may be act three in the drama of American political life. Describing the “disturbing freshness” of Edward Gibbon’s history of the Roman Empire, Mr. Kaplan writes:

The Decline and Fall instructs that human nature never changes, and that mankind’s predilection for faction, augmented by environmental and cultural differences, is what determines history.

Since the publication of The Grey Book, a call has gone out to make South Carolina the first state of the new unreconstructed South. Cory Burnell, the former director of the League of the South’s Texas chapter, has founded ChristianExodus.org, an online organization urging fundamentalist Christians to relocate to South Carolina. Rather than try to “redirect the entire nation,” Mr. Burnell hopes to “redeem States one at a time.” Working with the League’s South Carolina chapter, Christian Exodus.org plans to relocate 12,000 Christians annually to South Carolina with a secession date set for 2016.

Yet, there is a problem with the League’s plan for secession that may be more intractable than domination by the American Empire. Reversing a 35-year trend, blacks are now returning to the South in record numbers as they flee the high unemployment and crime rates of northern cities. As appealing as an independent Dixie may be for white Southerners, it is hard to imagine that Southern blacks will share that enthusiasm. Blacks make up nearly 30 percent of the population of South Carolina, according to the 2000 US census, and a high percentage of most of the rest of the South (Alabama, 26 percent; Arkansas, 16; Florida, 15; Georgia, 29; Louisiana, 33; Mississippi, 36; North Carolina, 22; Tennessee, 17; Texas, 12; and Virginia, 20.)

As their population continues to grow, southern blacks will increasingly take political control — first of the major cities — just as they have in Atlanta. Whites will flee to white enclaves and the new black establishment will gorge itself on what is left behind.

Thomas Chittum predicts an independent black nation in the South, with Atlanta as its capital. If that should happen, Mr. Chittum believes whites will abandon the South, but some, like the authors of The Grey Book one suspects, will stay and fight.

Readers of AR may not be ready to join Mr. Burnell when he moves his family to South Carolina next year. Some may not agree with the League’s position on every social and economic issue, and others may find its fundamentalism incompatible with a more scientific worldview. Still, The Grey Book is worth reading, if only for its unwavering defense of white people from a future that looks increasingly dark.

Pauline Tate is a descendant of Confederate soldiers. She lives in North Carolina.

| ARTICLE |

|---|

The Crime the Media Chose to Ignore

Mass murder, incest, rape — and media silence.

During 2004 and 2005, Americans were fixated on Scott Peterson’s murder of his wife and unborn son. News channels reported breathlessly on the smallest developments in the investigation and trial, and scrutinized Mr. Peterson, his mistress Amber Frey, and the lawyers’ performances.

The national media has virtually ignored another case that is even stranger and more shocking: Marcus Wesson’s murder of nine of his own children in Fresno, California. Not only were there more victims, but the circumstances were much stranger. Mr. Wesson carried on incestuous relations with several of his daughters and nieces for years, brainwashed the family into believing he was a Messiah, and made a murder-suicide pact with them. The media silence must certainly be due to the fact that Mr. Wesson is black. The media soft-pedal news about black crime because editors do not want to show non-whites in an unflattering light.

People who have known Marcus Wesson say he is highly eccentric and moderately intelligent. He has a large vocabulary and expresses himself in flowery language. He undoubtedly has an unusual influence on others.

In 1968, Mr. Wesson left the army, which had sent him to Europe as a medical orderly, and moved to San Jose, California. Then in his 20s, he moved in with a Hispanic woman, Rosemary Maytorena, who was in her 30s; the two had one son. In 1974, Mr. Wesson married Miss Maytorena’s daughter Elizabeth, who was 15 at the time. Over the next 16 years, he had ten children with her. His wife Elizabeth had a sister named Rosemary Solorio, who also appears to have been under Mr. Wesson’s spell. In 1986, she sent her seven children to live with the Wessons. The children had been molested in their own home and were reportedly happy to make the change. The result was a household of considerable size.

Mr. Wesson could not keep a steady job, and got most of his income from welfare. The family drifted from place to place, and some of its living arrangements were inventive. At one time the family lived in a 26-foot boat moored in Santa Cruz harbor. Mr. Wesson sometimes scavanged hamburgers out of a McDonald’s dumpster for his family to eat. The boat got him in trouble, however: He failed to list it as an asset on his welfare forms, and went to jail for welfare fraud in 1990. In the mid- and late 1990s, the family lived in a trailer and large army tent in the Santa Cruz mountains, on land with no running water. The Wessons also lived for a time in a decaying 63-foot tugboat off the shore of Marin County, California. Sometimes they lived in a school bus. By the late 1990s, the children of Marcus and Elizabeth Wesson were old enough to work, and Mr. Wesson used their money to buy the Fresno building in which the murders took place.

None of the children ever went to school. Mr. Wesson taught them at home, using flash-cards, school textbooks, and his own weird brand of Christianity. He became fascinated with David Koresh during the siege at Waco, Texas, in 1993, and made his family into his own personal cult. He described himself as Jesus Christ and police officers as Satan. When the family watched television coverage of the Branch Davidian siege, Mr. Wesson told the children, “This is how the world is attacking God’s people. This man is just like me. He is making children for the Lord. That’s what we should be doing, making children for the Lord.”

Mr. Wesson taught his family to be prepared to die if anyone ever tried to break up the household. He told his niece, Rosa Solorio, and his daughter, Sebhrenah Wesson, they were “strong soldiers,” who would hunt down and kill family members who betrayed him, and who might have to kill the family and themselves to prevent a break-up. Possibly in anticipation of such a massacre, Mr. Wesson bought ten coffins from an antique dealer.

Mr. Wesson was also fascinated by vampires, and gave himself and his daughters and nieces vampire names. His name for himself was Jevammarcsuspire, a mixture of Jesus, Marcus and Vampire.

Mr. Wesson began sleeping with his daughters and nieces after he got out of jail in 1990. According to trial testimony of Ruby Ortiz, née Solorio, one of the nieces sent to live with the Wessons, Mr. Wesson began molesting her when she was eight. Mrs. Ortiz testified that she loved Mr. Wesson at the time and at age 13 enthusiastically agreed to “marry” him. The marriage ceremony consisted of the couple putting their hands on the Bible and reciting marriage vows. Mr. Wesson “married” three of his nieces and two of daughters this way and had children by all of them. Mrs. Wesson fully approved of these incestuous unions. In fact, when Ruby Solorio ran away from home as a teenager, Mrs. Wesson persuaded her to come back to the house to take care of her son by Mr. Wesson. Mrs. Ortiz testified that Mr. Wesson could be cruel and jealous. He isolated his children from the outside world and beat her with a stick or baseball bat when she talked to boys or did not learn her lessons.

Despite this abuse, many in the family fondly remember their days with Mr. Wesson. He devised entertainments for the family, such as plays, concerts, and “ugly” contests, in which the children would dress up to be as ugly as possible.

The Wessons spooked their neighbors. Mr. Wesson weighs about 400 pounds, and one neighbor in Fresno described his hair as “one big, long greasy dreadlock. It was just caked in dirt and oil.” When Mr. Wesson would go out with the family, the women wore dark robes and walked behind him in silence with their eyes downcast. When the Wessons lived on the tugboat, the girls would row Mr. Wesson to shore and back. “They rowed him like they were slaves . . .” says one neighbor. “I had him pegged as some sort of Jonestown cult.”

All of the boys in the family moved out of the house when they were old enough, as did most of the girls. However, two of the daughters, Sebhrenah Wesson and Elizabeth Breani Wesson, and one of the nieces, Rosa Solorio, stayed with their father into adulthood, supporting the family. There were also several young children still in the house.

In 2003, the Wessons bought a house in Fresno that had been an office building. City authorities moved to evict the family because it was a non-residential building.

The prospect of eviction may have played some part in precipitating the murders. Mr. Wesson probably saw it as part of a plot against him and his family. But the primary trigger for the murders was a March 12, 2004 visit from Ruby Ortiz and Sofina Solorio, two nieces who had moved out of the household, and wanted Mr. Wesson to give them their daughters. He refused, and the family shouted curses at the two women, calling them “Judas,” “whore,” and “Lucifer.”

The two women left without their children, and returned with the police. Officers ordered Mr. Wesson to come out, but he fled inside the building. The police called the city attorney, who told them they had no legal right to go inside. Then Rosa Solorio and Mrs. Wesson came out of the building and reported Mr. Wesson had a gun. Police back-up and a SWAT team arrived. Just as they were taking positions around the house, Mr. Wesson emerged covered in blood and surrendered. Relatives of the victims blame police for not taking action sooner.

What the police found inside was so horrific that some of them went on administrative leave or into counseling. The nine bodies of Mr. Wesson’s children, who were all shot through one eye, were tangled up in a bloody pile of clothing. The victims ranged in age from one to 25. Two were Mr. Wesson’s daughters; the other seven were children of his daughters and nieces, all of them under eight years of age. The ten coffins Mr. Wesson had bought lined the wall of one of the rooms. That night six police chaplains reported to the building to soothe the detectives gathering evidence. The mayor of Fresno said the city would never be the same again after the largest mass-killing in its history.

It is possible that Mr. Wesson did not commit the murders. His lawyers say it was “strong soldier” Sebhrenah Wesson who shot the others and then killed herself. She was on top of the pile of bodies, and the gun was underneath her. Police found no gun residue on Mr. Wesson. Even if he did not fire the weapon, however, prosecutors say he could still get the death penalty for conspiracy to commit murder, and aiding and abetting murder.

Mr. Wesson went on trial March 3, charged with nine counts of murder and 13 counts of sexual assault. Many of his family members continue to support him. One of Mr. Wesson’s sons shouted out, “I love you, Dad” in court. Rosa Solorio says she still loves him, even though he killed the two children she had by him. She says Mr. Wesson is her husband, and she intends to stay faithful to him forever. She blames Ruby Ortiz and Sofina Solorio for causing the murders by trying to break up the family.

By the time this is published the jury will probably be close to a verdict. The media will have delivered a different verdict by remaining silent about one of the strangest mass murders ever committed in the United States.

| IN THE NEWS |

|---|

O Tempora, O Mores!

Born Victims

On March 8, 9,000 high school students marched in Paris to protest educational reforms announced by the government. The march attracted 700 to 1,000 black and Arab brawlers from the northern suburbs of the city who came to attack young whites. Small bands of thugs circulated through the crowd, beating up victims and stealing their wallets, purses, or mobile phones. All the victims were white, and the thugs attacked women as well as men. Dozens of victims were taken to the hospital. Police were caught flat-footed, and did little to help the victims; they arrested only eight people. The organizers of the demonstration ended it early because of the violence.

When asked why they had beaten the marchers, the attackers openly expressed their hatred of “little French people” and “little whites.” “If you have a face like a good Frenchman,” said one, “you’re a target. And especially if you look like a surfer with long hair.” They beat young whites, they said, because they were cowards and did not know how to fight. They also expressed resentment at whites’ wealth. “The people who were marching are those who want to succeed and who have a lot of stuff.”

The victims said the motive was clearly not just theft: Even when they gave up their cell phones or money immediately, the thugs still beat them up. Some just smashed the cell phones on the pavement and laughed. A group of public figures, along with 1,000 students, released a statement denouncing what they called “anti-white” attacks. [A Paris, les Casseurs ont Trappé et Volé de Nombreux Manifestants, Le Monde (Paris), March 10, 2005.]

When protesters marched again on March 15, unions provided an escort of several hundred. There were no attacks, but there were far fewer demonstrators than a week earlier. Student leaders said many whites were afraid to come out. [Union Escort for Protesting Paris Students, AFP, March. 15, 2005.]

The young men who attacked the protesters used the non-white ghetto slang term bolos to describe their victims. The word means “trendy young white” or “born victim.” The French newspaper Le Monde asked non-white high school students in the area from which the attackers came what the word meant to them. “It’s as though they had, ‘Come steal my stuff,’ written on their faces,” said one student. “Bolos look at the ground because they are afraid, because they are cowardly,” says another. Blondes are particularly likely to be bolos, but even non-whites can be bolos if they assimilate. “A North African can be a bolos if he thinks like a Frenchman,” says a student.

Black and Arab students respect and can even be friends with “whites who don’t take themselves for whites,” that is to say, who mimic the ways of the ghetto. Young non-whites particularly dislike whites who dress trendily, such as those who adopt skater or “Goth” fashions. These people, in the students’ view, are “not normal.” Bolos are weaklings and don’t move around in gangs. One student explained that they are vulnerable because of their small families. Young Arabs and blacks are likely to have older brothers who will avenge attacks. [Manifestations des Lycéens: Le Spectre des Violences Anti-”Blancs,” Le Monde (Paris), March. 15, 2005.]

French non-whites do not see themselves as part of the same nation as whites. Blacks and Arabs have started calling white Frenchmen Gaulois or Gauls, the name of the tribe that lived in France when the Romans conquered it. Some white Frenchmen use the term as well, as in “the Gaulois vote.” Young Muslims born in France, when asked their nationality, answer “Muslim” rather than French. [Olivier Guitta, Mugged by la Réalité, Weekly Standard, April 15, 2005.]

A Mystery

The Lowry Avenue Bridge in Minneapolis over the Mississippi River joins two neighborhoods: Northeast, which is mostly white, and North Minneapolis, which is mostly black. Between May and December last year, the bridge was closed for repairs, and mostly-white Northeast saw a 41 percent drop in crime. Crime at the other end of the bridge rose sharply. A liquor store owner in Northeast said he had noticed the crime drop himself. While the bridge was closed, there was less shoplifting and fewer customers trying to pass bad checks. A tattoo parlor owner in Northeast said the drop in crime was a popular subject of conversation in her shop. Some people even believed the bridge was deliberately kept closed longer than necessary.

Some Minneapolis residents are afraid to draw the obvious conclusion. A Northeast resident said, “Simply because crime is down, you can’t say it’s because the Lowry Avenue Bridge is closed. I think there’s implications for some racial attitudes that we have to be careful about.” A Northeast restaurant manager says it is difficult to know how the bridge affects crime: “I don’t know if the mystery will ever be revealed.” He did, however, concede that the bridge is “an open corridor to a whole different world.” The county commissioner duly declared himself “quite surprised” that many Northeast residents did not want the bridge reopened. [Mike Kaszuba, Was Lowry Bridge a Span to Crime? Star-Tribune (Minneapolis), March 29, 2005.]

Disparate Income

According to data from the US Census Bureau, in 2003, college-educated black women made more money than college-educated white women: $41,100 vs. $37,800. Asian women with bachelor’s degrees had the highest average pay at $43,700, and Hispanic women had the lowest, at $37,600.

Economists and sociologists say the black-white difference is due in part to the tendency of black women to work longer hours, hold more than one job, or return to work sooner after giving birth. But another factor is the premium on college-educated black women, especially in certain fields. “Given the relative scarcity, if you are a woman in the sciences — if you are a black woman — you would be a rare commodity,” says Roderick Harris of the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies.

College-educated men still earn more than college educated-women, with white men earning the most: more than $66,000 per year, compared to $52,000 for Asian men, $49,000 for Hispanics, and $45,000 for blacks. [Disparity Found in Degreed Women’s Earnings, AP, March 28, 2005.]

On March 21, the Canadian government unveiled a five-year, $56-million campaign to “get tough on racism.” The plan grew out of a government survey that found 18 percent of Canadians said they had suffered some form of racial discrimination, coupled with the fact that, thanks to immigration, Canada is becoming increasingly non-white. In 1980, non-whites — ”visible minorities” in Canadian government-speak — were just one percent of Canada’s population. The figure is now 13 percent, and is expected to reach 20 percent by 2017.

Fighting Internet “racism” is part of the effort. There will be a hot line so Canadians can report Internet “hate” sites, and the government will pressure Internet Service Providers to shut down websites it doesn’t like. The government will also define and keep track of hate crimes, meet the “needs” of victims, and “rehabilitate” perpetrators. The authorities will also work closely with employers, unions, immigrants and Canadian “aboriginals” (but apparently not with whites) to root out employment discrimination. There will also be a “Welcoming Communities Initiative,” to “foster a more welcome environment” for immigrants.

Fighting “racism” is one of Justice Minister Irwin Cotler’s top priorities. “We have to send out the message unequivocally,” he says, “as a government and as part of our shared citizenship and shared values, that our Canada is one in which there will be no sanctuary for hate and no refuge for bigotry. We will use all the panoply of remedies to bring that about: legal remedies, intercultural dialogue, promotion of multiculturalism, anti-discrimination law and policy.” [Elizabeth Thompson, Racism Battle Gets $56 million, Gazette (Montreal), March 21, 2005.]

Unwelcome Guest

In early March, Hakeem Hakeem went on a rampage in the suburbs of Melbourne, Australia. First, he beat and raped a woman. Five days later he raped another woman. The next day he raped, robbed, and tried to kill a 60-year-old woman. The next day he forced a man to rape yet another woman before raping her himself and sexually assaulting her with a tree branch. Mr. Hakeem is a 19-year-old immigrant from the Sudan. By the time police got him into court, he had been in Australia for just three weeks. [Accused Serial Rapist in Australia for Just 3 Weeks, Daily Telegraph (Sydney), March 16, 2005.]

State of the Black Union

Every year since 2000, black radio talk show host Tavis Smiley has put on what he calls a “State of the Black Union” conference. This year it was in suburban Atlanta during the weekend of Feb. 26, and attracted such luminaries as Jesse Jackson, Al Sharpton, Louis Farrakhan, Rep. John Conyers and former US Surgeon General Joycelyn Elders. The theme was black political activism.

Many blacks say the 2004 presidential campaign ignored “their” issues, and Mr. Smiley said black leaders should draw up a “contract with black America” that politicians would have to sign. “The next time you come calling on our vote,” he said of politicians, “you come correct on the contract or you don’t come at all.” The audience of 2,000 whooped with delight. Joseph Lowery, former head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, preferred a “covenant” to a “contract,” saying, “We’ve got to recapture that spirituality; that’s our strength.” Mr. Smiley agreed, saying, “Black folk have always been the conscience of this country. We are doing our part to help redeem the soul of America.”

Mr. Farrakhan said any contract should be between blacks and their own leaders, in order to present a unified front in the face of white power. “Power concedes nothing without a demand,” he said, “but power won’t even concede to a demand if it comes from a weak constituency that looks like it’s lost its testicular fortitude.”

Predictably, President Bush emerged as the villain. Mr. Farrakhan derided the President for going to war with Iraq, accusing him of believing that “no dark nation should have a weapon of mass destruction.” Rev. Eddie Long had to justify accepting an invitation to the White House: “Just because we went to the house does not mean we had intercourse,” he explained. [Charles Odum, ‘Contract’ Urged for Black Issues, AP, Feb. 27, 2005.]

Black Social Security

President Bush is trying to persuade blacks to support his proposal to privatize Social Security, arguing that they are shortchanged by the present system because they tend to die younger than whites. “African-American men get on average two to four years of retirement benefits, while white Americans get 10 to 12 years of benefits,” says Republican National Committee spokesman Tara Wall.

The GOP’s critics say this appeal won’t work, because blacks rely on Social Security income far more heavily than whites (38 percent — as opposed to 18 percent of whites — have no other retirement income). “It is one of the best deals that poor and working poor can get, and blacks are unfortunately over-represented in those groups,” says black congressman Charles Rangel (D-NY). “If one of the appeals to blacks is that they’re not getting a fair shake because they die earlier, it would seem to me that they would at least address the question of why they die earlier and what we can do about it.” [Edmund L. Andrews, GOP Courts Blacks, Latinos, New York Times, March 20, 2005.]

Sins of the Father

Philadelphia has joined Chicago in forcing firms that do business with the city to report whether they ever made money from slavery. The law, which went into effect in March, says that any company that gets a city contract must file an affidavit within 90 days stating it has checked its records for any evidence of profits from slavery. If there ever were such profits, the company must list the names of the slaves and slave owners. If the business does not file the affidavit or lies in it, it will lose the contract.

“This is a chance to put in place an essential element — corporate disclosure and transparency,” says city council member Blondell Reynolds-Brown, who sponsored the bill. “We will arrive at a new era when corporations are able and willing to face their past and make proper amends, whatever they may be, for any egregious wrongdoings.” [Angela Couloumbis, Past Slave Profits Focus of Council Bill, Philadelphia Inquirer, March 3, 2005, p. B-4.]

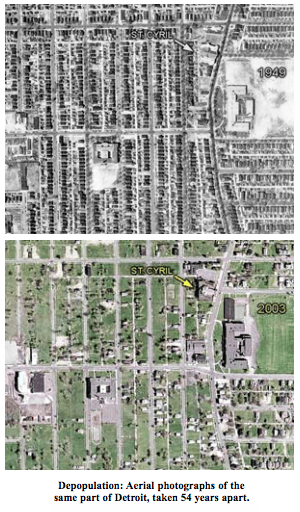

Detroit was one of the first major American cities to get a black mayor, and has been run by blacks ever since 1973. Some blacks therefore call it the Capital of Black America, but the capital is in bad shape. Its population of 911,000 is half what it was in the 1950s, and the city is expected to lose another 50,000 by 2010. The declining tax base means Detroit faces a three-year budget shortfall of $389 million, and is on the brink of bankruptcy. Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick is trying to stop the red ink by firing 687 city employees, and cutting everyone else’s pay by ten percent. This will not be enough. Decades of featherbedding have left Detroit with 1.4 city workers for each 1,000 residents, well above the one per 1,000 average in other major cities. The mayor plans to save money by shutting down overnight bus service and closing the aquarium. He is also considering closing the zoo, cutting back on public medicine, and turning off some street lighting.

Schools have been getting the axe. The superintendent fired 372 teachers before Christmas, and plans to close 40 schools this summer. According to projections, the number of schoolchildren will decline to 100,000 by 2008, half the 1999 figure. This would mean closing 110 of 252 schools, and firing more than a quarter of the district’s 21,000 employees.

Businesses have fled, leaving an unemployment rate of 14 percent, nearly double the state average, and almost three times the national average. Detroit squeezes 5.5 times more in taxes out of its residents than the average Michigan city. Part of this is due to a city income tax, which takes the place of all the real-estate tax the city does not collect on block after block of abandoned buildings. As if this were not enough, the city is considering a new head tax of $252 a year on the people it still has.

A generation ago, blacks spoke hopefully of a renaissance. Now the words they use are “cataclysmic,” “dire,” and “grave,” and the vocabulary is not likely to change. “I see no turnaround imminent,” says David Lippman, chief economist at Comerica Bank. “It does gravitate to a downward spiral.” (see “The Late Great City of Detroit,” AR, Aug. 1991, for an analysis of Detroit’s long decline).

Mayor Kilpatrick doesn’t want to be known as the man who finally ran the city onto the rocks. He says he’s been working out with weights to get into “fighting shape” so he can tackle Detroit’s woes. “We’ve been a black eye on the landscape of America for too long. I don’t want that stigma attached to me.” The mayor could start economizing closer to home. Not long ago he stuck the city with a $24,995 bill for a 2-year lease on an SUV for his wife. [Jodi Wilgoren, Shrinking, Detroit Faces Fiscal Nightmare, New York Times, Feb. 2, 2005, p. A12.]

Mexican Fears

Mexican politicians routinely campaign for votes in the United States, and plans are underway to make the US a Mexican voting district for the next presidential election in 2006. That worries Mexican Foreign Relations Secretary Luis Ernesto Derbez — but not because it treats the US as if it were a province of Mexico. In testimony before the Mexican senate, he said American authorities might use Mexican election day to identify and catch illegal immigrants. Mr. Derbez also worries that a massive voter turnout among Mexicans in the US might encourage anti-immigrant sentiment. [Voting by Mexicans Abroad Spurs Concerns, AP, March 20, 2005.]

During the 1990s, more African blacks came to the United States than were ever brought here as slaves. African immigrants first began coming in large numbers in the 1970s as refugees from Ethiopia and Somalia. During the 1990s, black African immigration tripled. At more than 600,000, Africans now make up 2 percent of the US population and, along with Caribbean-born blacks, account for 25 percent of black population growth. If illegals are counted, the numbers could be four times higher.

Most of today’s legal African immigrants come from Nigeria and Ghana. Many go to New York City, but others head for Washington, Atlanta, Chicago, Los Angeles, Boston and Houston. Refugees, mainly Somalis, now live in Minnesota, Maine and Oregon.

Daouda Ndiaye is an immigrant from Senegal who won a visa in the diversity lottery in 1994. Mr. Ndiaye first worked in a sporting goods store and is now a translator. Thanks to the family reunification provisions of US immigration law, he has already brought in two of his six children.

Because many African immigrants are the most ambitious and capable of their people, some of their countrymen predict a brain drain that will hurt Africa. Others point out that African immigrants send back more than $1 billion annually to their families. Some Americans fear the economic success of African immigrants (who generally do not blame whites for their problems) will reflect badly on American blacks. “Historically, every immigrant group has jumped over American-born blacks. The final irony would be if African immigrants did, too,” says Eric Foner of Columbia University. [Sam Roberts, More Africans Enter US Than in Days of Slavery, New York Times, Feb. 21, 2005.]

Dutch Deserters

The Dutch used to take pride in their open, anything-goes social liberalism. They welcomed hundreds of thousands of non-white, primarily Muslim refugees and immigrants, gave them welfare, and did not ask them to assimilate. The immigrants — now ten percent of the population — kept to their own customs, which in many ways are antithetical to Dutch liberalism. Last November, a Muslim fanatic murdered prominent filmmaker Theo van Gogh, a critic of radical Islam.

The killing seems to have awoken the Dutch to the threat they face, but instead of fighting, many Dutch are running. “Our website got 13,000 hits in the weeks after the van Gogh killing,” says Frans Buysse, who operates an agency that helps people emigrate. “That’s four times the normal rate.” Immigration consultant Paul Hiltemann says he was inundated with phone calls and e-mail after the murder. “There was big panic,” he says; “a flood of people saying they wanted to leave the country.” Five years ago most of the clients he served were farmers looking for more land. Of those seeking to leave now, he says, “They are successful people . . . urban professionals, managers, physiotherapists, computer specialists.”

Ruud Konings is one who wants out. “When I grew up,” he says, “this place was spontaneous and free, but my kids cannot safely cycle home at night. My son just had his fifth bicycle stolen.” His children are reluctant to go to school because “they’re afraid of being roughed up by the gangs of foreign kids.” His wife believes the Dutch have brought the situation on themselves. “We’ve been too lenient; now it’s difficult to turn the tide.”

Most Dutch deserting their own country have their eyes on Canada, New Zealand, or Australia. [Marlise Simons, More Dutch Plan to Emigrate as Muslim Influx Tips Scales, New York Times, Feb. 27, 2005.]

Thinking the Unthinkable

In Britain, just as in the United States, there is a huge gap in academic achievement between blacks and whites. In 2001, the British government set up a plan to eliminate the gap, and in 2003, it put another £10 million into the effort. Needless to say, the British have nothing to show for their money; the gap still yawns. Again, as in America, the British are prepared to try just about anything in the hope of getting blood from turnips.

Trevor Phillips, the black chairman of Britain’s Commission for Racial Equality, says the time has come for Britain to “embrace some new if unpalatable ideas” — including setting up separate classes for black boys. Mr. Phillips thinks segregation could boost self esteem, give blacks positive role models, and reform a “not cool to be clever” mentality. [Danielle Demetriou, Teach Black Boys Separately, says Phillips, The Independent (London), March 7, 2005.]

Sneaking across the US-Mexican border can be hard work, especially if you are pregnant. On Feb. 27, US Border Patrol agents found a pregnant Mexican woman by the road outside of Laredo, Texas. The woman, who was in labor, had been abandoned by smugglers because she could not keep up. Agents arrested her, then delivered her baby — an automatic US citizen — in the back of their vehicle on the way to the hospital. The woman named her daughter Sarai Marisol after the agent who delivered her, Marisol Cantu. Young Sarai — 10 weeks premature — will receive first-world medical care at US taxpayer expense in a Corpus Christi hospital. As the mother of a US citizen, the woman will probably be allowed to stay. [Illegal Alien Gives Birth After Arrest, AP, March 4, 2005.]

| LETTERS FROM READERS |

|---|

Sir — I know you would have given much not to have had to dedicate your April issue to Sam Francis, but it is, indeed, a fine tribute. Yours and Mr. Dickson’s personal reflections were moving. I learned much about Sam that I did not know.

I liked the spirit of the man, and how he could cut through the nonsense of a subject and get to the deep-down grit. I always looked forward to his take on the issues of our times, since so many of his views concurred with mine. I respected his determination to look out for the interests of his own race. It was clear he understood the damage that had been done to both blacks and whites because of the form of “liberation” that was thrust on us.

I knew that his frankness had done him in at the Washington Times, and I often wondered about the degree to which his future had been undermined or sidetracked because he was above-board and open with his views. You clarified some of this in your article.

Two days before the news of his death, I had sent Sam a get well note. So, like everyone else, I was totally unprepared for the end.

I understand the long-range and overall importance of what is lost with Sam’s death. You and Mr. Dickson allude to it in your articles. It was not just his knowledge, intelligence and wit that made him important, but his very presence. The fact that Sam Francis was out there doing his upfront, no-nonsense stuff, gave a kick in the pants to others to be more courageous, even if they could not be quite so candid. Mr. Dickson called him irreplaceable and I think this will be even more obvious as time goes on.

Elizabeth Wright, Editor

Issues and Views

Sir — I appreciated immensely your and Sam Dickson’s obituaries of Sam Francis. I have to say “appreciated” because “enjoyed” would be completely inappropriate in these very sad circumstances. I spent only a few hours with Sam but I took to him instantly. I had heard about his gruff manner in advance but it did not bother me. There was so much evident sincerity underneath — together with a dry sense of humor never far away.

Your and Mr. Dickson’s obituaries fitted in completely with my own brief impressions. The theme of courage — particularly appropriate because he had more to lose than most — sends out some admirable signals to those who are less intrepid. The utter cowardice of conservatives is equally visible on both sides of the big ocean.

I particularly liked Mr. Dickson’s passage on calculation. It is the hallmark of every politician. “What’s in it for me?” is the overriding question that determines all decisions and stances. How different was Sam!