The Damned and the Dead

Jared Taylor, American Renaissance, February 8, 2012

Frank Ellis, The Damned and the Dead: The Eastern Front through the Eyes of Soviet and Russian Novelists, University Press of Kansas, 2011, 376 pp.

I would never have considered reading this book if the author had not given me a copy — and for the fact that the author is not just anybody. Frank Ellis, a lecturer in Russian and Slavonic studies at the University of Leeds in England, spoke on “Racial Hysteria in Britain” at the 2000 AR conference. Six years later he provoked hysteria on his campus by pointing out that there are racial differences in intelligence, and that genes account for a large part of them. Prof. Ellis stuck to his guns and laughed at the very idea of apologizing. He is, in short, a fine fellow.

But what could interest AR readers in a book about Soviet and Russian novelists? As I discovered, a great deal.

The Damned and the Dead is many books in one — all good. It is certainly a survey of Russian-language fiction written about the Soviet war with Nazi Germany. However, it is also full of keen observations about the nature of war and combat that no doubt draw on Prof. Ellis’s own experiences in the British Special Forces. At the same time, it recounts the struggles of Soviet writers to get realistic fiction past the censors, and explores the terrible effect of Stalin’s tyranny and Communist ideology on the Red Army’s ability to fight. It is this analysis of what happens when ideology terrifies and blinds people — just as today’s ideology about race terrifies and blinds people — that is especially relevant for AR readers. As Prof. Ellis warns, with a quotation from John Stuart Mill:

The dictum that truth always triumphs over persecution is one of those pleasant falsehoods which men repeat after one another until they pass into commonplace, but which all experience refutes. History teems with instances of truth put down by persecution.

We are living in a time of persecution, and it is well to be reminded just how far persecution can go. Today’s “anti-racists” share the mental outlook of Soviet commissars, and would probably be just as brutal if they had the power.

The Nature of War

Prof. Ellis says this about the war on the Eastern Front:

Our remote ancestors’ propensity for violence was spontaneous and local; in the twentieth century it was global, systematic, and planned. It is therefore not entirely accurate to characterize Stalingrad and the other battles on the Eastern Front as a regression to barbarism. Rather they represent a progression to a new type of barbarism, one dominated by technology and influenced by the mass media.

What made men endure the horrors of the Eastern Front? Prof. Ellis writes that all armies depend on “the fundamental decency of the soldier’s desire to stand by his fellows.” At the same time, soldiers find strength in the belief that they will not be forgotten if they die. Prof. Ellis quotes an American Marine:

Past deeds are a young Marine’s source of pride, inspiration to face danger, and reassurance that death in battle isn’t consignment to oblivion. His buddies and all future Marines will keep the faith.

If, as Prof. Ellis writes, “the sacrifice of the dead imposes an obligation on the living to remember” then war literature of the best kind is a remembrance of the dead, an expression of reverence for the fallen. Prof. Ellis assures us that by this standard, Soviet and Russian war literature is unsurpassed.

Many of the novels have battle scenes “of astonishing power and virtuosity,” and also treat harrowing themes unfamiliar to Western readers, such as the state of mind of innocent men condemned to death on charges of cowardice or treason — men who were, writes Prof. Ellis, “legally defenseless, alone and despised.” The Damned and the Dead, a 1990s novel by Victor Astaf’ev from which Prof. Ellis takes the title of his own book, in addition to being a shattering account of men at war, raises a profound question that is absent from any other nation’s literature about the Second World War: Is it possible to wage a just war against even a terrible invader when it means defending the despicable regime of Stalin and his henchmen? Wrenching themes of this kind are a special reward for those who read these works.

Censorship

Censorship in the Soviet Union did not officially end until August 1, 1990. Official soviet literature about the war, therefore, was about mass heroism in the Red Army and the pure evil of Nazism. Prof. Ellis tells us that some of it is competent story-telling but much of it suffers from “aesthetic barrenness and emotional sterility.”

During the war, censors read every letter sent from the front, and wrote reports to the authorities on what soldiers were thinking. Those reports have now been unsealed. Soldiers often complained that Soviet newspapers were full of lies about the progress of the war, and they wrote bitterly about collectivization. Curiously, the reports mention almost no criticism of Stalin, even though many soldiers must have written about him. Prof. Ellis concludes that the censors were censoring themselves! — that certain ideas were too dangerous even to pass up the chain of command.

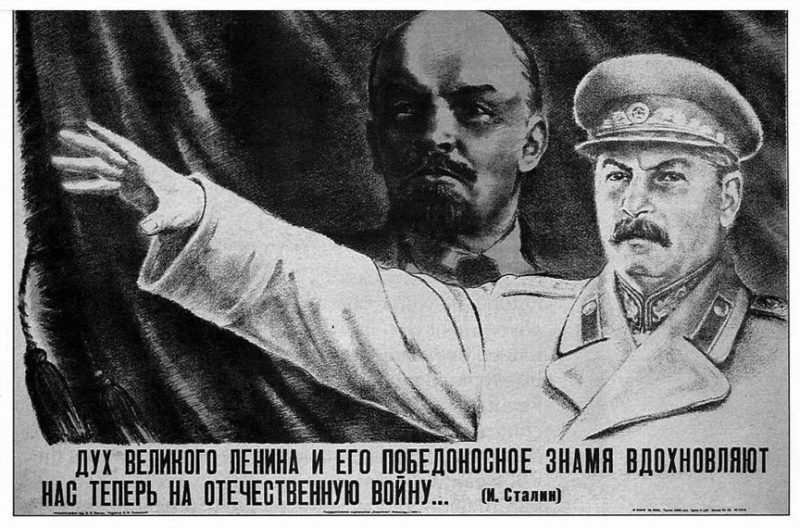

“The spirit of the great Lenin and his victorious banner inspire us now in this patriotic war.” — J. Stalin

In the post-war period, a prominent act of censorship was the “arrest” in 1961 of the manuscript of Vasilii Grossman’s Life and Fate. The book, on which Grossman had spent 10 years, was a merciless dissection of the Soviet state, both at war and at peace, and the authorities considered it far more subversive than Doktor Zhivago, which was published in 1957 outside the Soviet Union. A politburo member, Mikhail Suslov, told Grossman that his book might be acceptable to Soviet readers in perhaps 200 or 300 years. The book was finally published in the West in 1980, and in the Soviet Union in 1988.

Treason

Prof. Ellis states bluntly what could have been a fatal handicap for the Red Army: “[T]he German invasion of the Soviet Union exposed a lack of allegiance on the part of large numbers of Soviet citizens toward their leaders that has no parallel in the history of war.” So categorical an indictment is startling, but Prof. Ellis may be right.

Collectivization, which had continued through the 1930s, obliterated traditional patterns of rural life. The peasants who had suffered most — they called collectivization a “second serfdom” — were now asked to fight for a government they despised, and there is no question that many deserted or refused to fight.

Non-Russian populations in Ukraine and Belorussia especially hated the Soviets because of collectivization and the suppression of Christianity, and welcomed the Germans as liberators. (Indeed, Prof. Ellis argues that if the Germans had cultivated widespread hatred of Stalin rather than mistreating the Soviet people they might have won on the Eastern Front.) Germans occupied these areas for as long as three years, and officers of the NKVD (secret police) and of SMERSH, the counterintelligence agency set up in 1943, had some reason to suspect that any Ukrainian or Belorussian who had survived Nazi rule was a de facto collaborator.

The Soviet Army purges of 1937 were also a vivid and poisonous recent memory in the military. Many senior officers were executed on charges of treason, and the NKVD and political commissars assumed that only treason could have caused the devastating defeats of 1941. They believed that anyone who had contact with the enemy and then returned to Soviet lines was at least a coward, if not a traitor or spy.

The top five military officers of the Soviet Union in November, 1935. Left to right: Marshals Mikhail Tukhachevsky, Semyon Budyonny, Kliment Voroshilov, Vasily Blyukher, and Aleksandr Yegorov. Only Voroshilov and Budyonny survived the purge of officers.

It was this desperate combination of suspicion, hatred, collaboration, and unending defeats that prompted Stalin’s famous “not a step backward” order of July 1942. No solider was to retreat a single step “without the order of a superior commander.” The punishment was death on the spot. As Prof. Ellis writes, this often made strategic retreat impossible:

If the junior commander has to make the decision, the risk that he will be investigated for desertion or dereliction of duty will always enter into his calculus of decision-making. Such considerations cannot promote effective command.

The Red Army set up “blocking detachments” that prowled behind the front line, killing or arresting anyone who took a “step backward.” Prof. Ellis quotes from a novel in which the character Len’ka is separated from his unit and wanders into an NKVD blocking detachment: “Soldiers such as these Len’ka had not seen before: rosy-cheeked, well fed, looking as if they had been fed on good food, well kitted out in new helmets . . . .”

An estimated 40,000 men served in these detachments, and they took their jobs seriously. According to Soviet records, in the brief period from August 1 to October 15, 1942, they “detained” no fewer than 140,755 soldiers who “ran away from the front line.” Of that number 3,980 were arrested, 1,189 executed, 2,961 sent to penal units, and 131,094 returned to their units or to transit centers.

Many men were executed with no real investigation or recourse, and solders were often shot in front of their units. Men “returned to their units” were probably branded as cowards and mercilessly abused. There is no telling where men went from “transit centers;” often it was to concentration camps. Penal units were punishment battalions sent into the worst, most dangerous engagements, where offenders were, in the language of Soviet doctrine, to “expiate their crimes against the motherland in blood.”

British executions during the First World War for desertion or cowardice — 346 for the entire war — give us something of the scale of Soviet retribution. The above figure of 1,189 executions was for a period of just two and a half months.

As Prof. Ellis notes, harsh measures flowed logically from Marx’s concept of war:

If the interests of the working class were threatened by either internal or external enemies, then all measures were justified. Extermination of the class enemy was the obligation that history imposed on the Communist Party.

This atmosphere of suspicion and punishment gave rise to the theme of “encirclement” that Prof. Ellis tells us is common in Soviet war literature. Soldiers who were surrounded by the enemy but fought their way back to their lines were not commended for resourcefulness but treated as traitors, and the injustices that followed are a staple of Soviet literature. Soldiers captured by the Germans but who had escaped were often treated as if they were spies.

Prof. Ellis notes that the question of collaboration with the Germans is still a very sore subject in Russia. Supporters of the Soviet regime wrote novels in which blocking units were the heroes; their courage and iron discipline saved the motherland from traitors and cowards. And yet, what kind of regime must make heroes of men who shot down their own countrymen by the thousands for cowardice and treason? Prof. Ellis concludes that blocking divisions and penal units may have been a tragic necessity for a hated regime with its back to the wall:

If . . . results are what matter, at whatever price, then it could be said that the whole NKVD apparatus of censorship, rooting out dissenters, blocking detachments, tribunals, executions, and agitprop succeeded. From this perspective, one that many patriotic Russians will find too awful to contemplate, the NKVD might be entitled to claim some credit for the Soviet victory.

Prof. Ellis writes that no army may ever have treated its men so badly: “The stupefying cruelty and indifference of the Soviet military leadership toward its own troops, both in training and in combat, cannot be explained entirely by incompetence.” He is not sure whether this had roots in some ancient strain of Russian savagery, but the brutality of the Stalinist regime certainly spread to the army. New recruits were treated little better than gulag inmates, and the result was “to reduce healthy, able-bodied young men to scrofulous, pediculous [lice invested], apathetic wretches.”

Soldiers became savages themselves, and turned on weaker recruits, causing many deaths before Red Army units even met the enemy. Prof. Ellis speculates that this may have at least had the effect of removing weaklings before they became liabilities in combat. He notes that in the 66th Soviet Army there were 32 cases of actual starvation! Many of those who were sent into battle were sacrificed on tactically pointless objectives. At least in fiction — and probably in real life — men with strong Christian faith survived best.

Many scholars have wondered why Soviet troops did not mutiny. “There is no real explanation of why the soldiers tolerated being treated as if they were cattle for the slaughter,” writes Prof. Ellis. Alexander Solzhenitsyn also agonized over this question. From June 22 to July 3, 1941, just after the start of the German invasion, Stalin was in a state of paralysis, and the generals could easily have removed him. Why didn’t they?

Part of the explanation may be the mentality left behind by the purges:

The execution of thousands of officers, among whom were some talented commanders, was bad enough [from a military point of view]; almost as bad was the psychological damage done to the survivors. Showing initiative, expressing one’s own ideas, and leading — all the things than an officer in a modern army should do — became dangerous, so officers blindly obeyed orders.

Such men could not have raised a finger against Stalin. Prof. Ellis writes that many were in a state of such psychological surrender to the party that they were incapable of individual action on the battlefield. There was also a dual army command — political as well as military — that often resulted in bad decisions or no decision at all. Prof. Ellis cites a scene from a novel in which a political officer takes over the only communications link so he can make political speeches just when it was vitally necessary to send a message to correct artillery fire so as to hit the enemy.

What about America?

Prof. Ellis quotes the British general Sir John Hackett:

What a society gets in its armed services is exactly what it asks for, no more and no less. What it asks for tends to be a reflection of what it is. When a country looks at its fighting forces it is looking in a mirror; the mirror is a true one and the face that it sees will be its own.

Prof. Ellis’ The Damned and the Dead paints a harrowing picture of a nation under a cruel, mentally shackled regime that was at the same time fighting for survival against a terrifying enemy. The Soviets got the army they asked for.

What army do we get? Although we do not have commissars who make political speeches during combat, we certainly have orthodoxies that weaken our forces. Blacks and Hispanics are less intelligent than whites or Asians, yet they must be promoted in equal numbers. Just as giving commissars influence over military decisions hurt the Soviet Army, promoting incompetents hurts our army. Dozens of studies have shown that women are physically weaker and more susceptible to post-traumatic stress disorder than men, and yet no one dares decry the folly of putting them on combat ships.

Plenty of officers know that “diversity” is a weakness on the battlefield but just like the Soviet officer corps after the purges, they are paralyzed by fear, and dare not say so. Only after he retired did Army Green Beret Major Andy Messing denounce the foolishness of mixing men of different races or religions in Special Forces units. Only after he no longer had command authority did he point out that men fight better alongside comrades like themselves.

Our armed forces have not faced a serious enemy since they fought the Chinese during the Korean War. At that time, there was no nonsense about women in combat, and although units had been recently integrated, there were still very few affirmative-action officers.

Would today’s American military even hold together in the face of a determined, modern enemy like the one that sliced through the Red Army in the summer of 1941? If our army did not shatter completely, it would soon rid itself of the dangerous ideologies that weaken it but still permit it to seem impressive in the face of Third-Worlders with rusty Kalashnikovs. In a true test, what would be the cost — in corpses — of the silence of cowards?

Prof. Ellis notes that Alexander Solzhenitsyn had particular contempt for Bertrand Russell’s pacifist statement, “better Red than dead:”

In this horrible expression . . . there is an absence of all moral criteria. Looked at from a short distance these words allow one to maneuver and continue to enjoy life. But from a long-term point of view it will undoubtedly destroy those people who think like that. It is a terrible thought.

This is a perfect description of white men who remain silent while every once-white institution plunges deeper into the insanity of “diversity.” Whites are silent because they want to survive the purge, but it is silence that permits the purge, and even if they survive, their children will not.

When Prof. Ellis fought orthodoxy on his own campus, the University of Leeds, he saw the same cravenness he had studied as a scholar of the Soviet Union. As he wrote in a letter to American Renaissance in September 2006:

Modern liberalism is truly depraved. Even now I am staggered by its boundless capacity for hypocrisy and lying — perhaps after all this I should not be, but I am. I know members of the Leeds faculty who share my objections to the cult of multiculturalism, but they remained silent. When I visited the university none could look me in the eye. I shall not name and shame them but they know who they are; they have disgraced themselves.

You do not really know people until there is a crisis. One of the most depressing things in this world is to discover that people, who you thought had some reserves of moral courage (physical courage is not the same thing), actually have the soul of a terrified apparatchik. I feel no anger towards these people; more disgust, I would say.