I Believe Black Americans Face a Genocide. Here’s Why I Choose That Word

Ben Crump, The Guardian, November 15, 2019

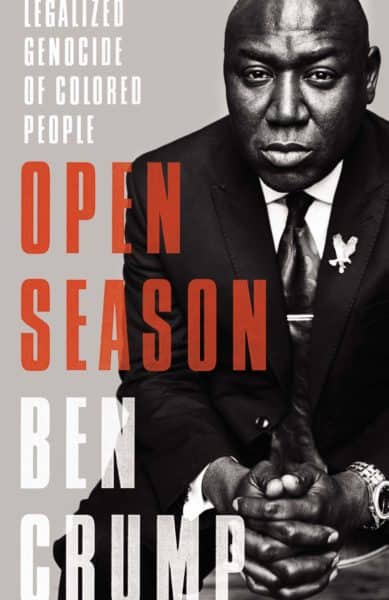

In the weeks since the release of my book, Open Season: Legalized Genocide of Colored People, the question I’ve been asked most often is whether my use of the word genocide in the title was meant to be intentionally provocative, rather than reflective of reality.

Surely, genocide is too strong a word for the maltreatment of black people in America, some interviewers have suggested. True genocide is something that happened in Nazi Germany, Armenia and Rwanda, not the United States of America.

Yet we don’t need to look any further than the definition contained in article 2 of the United Nations’ 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide: “Genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.” It then goes on to describe the acts as “killing, causing serious bodily or mental harm, deliberately inflicting conditions calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part, imposing measures intended to prevent births, or forcibly transferring children of the group to another group”.

The first case for charging the American government with the genocide of black Americans was brought in 1951 by a group called the Civil Rights Congress (CRC) in We Charge Genocide: The Historic Petition to the United Nations for Relief from a Crime of The United States against the Negro People.

The CRC was attacked, accused of exaggerating racial inequality, and disbanded in 1956. In hindsight, the paper – and its charge of genocide – was prescient and has stood the test of time.

Bryan Stevenson, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, has documented 4,400 racial terror lynchings so far. He has brought the historical evidence of genocide to life in an exhibit at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice; there, visitors walk under 800 steel columns representing black Americans who were lynched – some bearing names, some printed with “unknown” and the location of the lynching.

Rather than fading into a shadowy past, the case for charging genocide has – if anything – only grown stronger and clearer since the CRC first brought its petition.

Trayvon Martin, Philando Castile, Tamir Rice, Michael Brown, Stephon Clark – daily, the news is filled with documentation of black people wrongfully killed by police, of black lives treated as though they had no value, of lives extinguished without accountability and without justice.

But the evidence of genocide doesn’t stop with outright murder. The mass incarceration of black people testifies to a prison industrial complex that uses black lives as fuel to feed its profits. Consider the generational harm of incarcerating black people, who make up only 13% of the population but 27% of all arrests, 33% of those in jail or prison and 42% of those on death row. We see genocide in the generations of black families who have been economically and psychologically destroyed by a justice system that incarcerated poor blacks for using crack cocaine, while slapping the wrists of white professionals who used cocaine in its white powder form. We see that hypocrisy continue today as opioid use is deemed an “epidemic” and disproportionately white users are treated as addicts in need of treatment. We see it as the government devises ways to profit from the legal marijuana industry while thousands of black Americans rot in prison for possessing or selling weed to support their families.

We see it in the masses of black Americans who have been forced or coerced into felony convictions or plea deals, costing them the basic essentials of a successful life – an act I call in my book “killing us softly”. Consider the cascade of consequences that follows a felony label, which disproportionately affects black Americans. Trumped-up felony convictions and plea deals leave thousands of black Americans unable to vote; unable to access housing; unable to hold a wide range of jobs, from nail tech to childcare worker; unable even to purchase life insurance, rendering them the walking dead.

We see it in the rampant environmental racism that threatens the lives of black people in low-income neighborhoods across the country. Consider that the most polluted zip code in Michigan, 48217, is 84% black. Isn’t it ironic that hundreds of thousands of black Americans are in prison for selling small amounts of drugs because prosecutors and judges maintained they were poisoning the community – but when it came to Flint, where the whole community was literally poisoned, not one official was punished?

If that isn’t enough evidence of genocide, consider the last two acts contained in the UN’s definition – preventing births or forcibly transferring the children of one group to another. In my book, I document how black people have been sterilized without their knowledge or against their will for decades and are still coerced into sterilization to reduce a prison sentence. For much of the last century, a majority of states carried out eugenics laws, resulting in the sterilization of nearly 65,000 Americans, most often women of color. In California, nearly 150 incarcerated women were sterilized between 2004 and 2013, according to the Center for Investigative Reporting. And as recently as 2017, a Tennessee judge offered to reduce criminal sentences by 30 days for individuals who agree to sterilization or long-form birth control implants.

Black children are much more likely to intersect with the social welfare system, where they are likely to end up in foster care or adopted – that is, raised by a group other than their own. In New York City, 53% of children in foster care are black, though only 25% of children in the city are black. In Minnesota, black children are three times more likely to be removed from their homes than white children. In many cases, the “crime” that led to the children’s removal is their parents’ poverty, a condition imposed or fostered by society.

The physical, financial, mental, and even spiritual deaths inflicted on black Americans are evident everywhere – in substandard schools, in the food deserts that leave black communities without food to survive or thrive, in impoverished neighborhoods subject to polluted water and air.

That the use of the word genocide would prove so shocking suggests that many Americans lack both a knowledge of our history and an awareness of the circumstances all around them. In Open Season I have tried to hold a mirror to America’s face, because we know our nation can and must do better. Like the CRC members declared nearly 70 years ago, I charge genocide. The case is clear.