Brigitte Bardot: From Sex Symbol to French Patriot

Robert Griffin, American Renaissance, January 2007

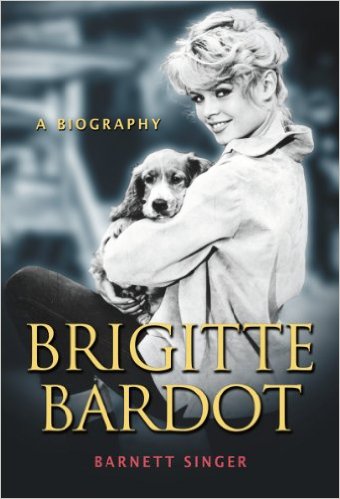

Barnett Singer, Brigitte Bardot: A Biography, MacFarland & Company, 2006, 197 pp.

It all started, reports biographer Barnett Singer, with not-yet-15-year-old Parisian Brigitte Bardot’s prim and schoolgirlish cover photo in the May, 2, 1949 issue of Elle magazine. Among the many who took notice was Roger Vadim Plemiannikov, 21, later to be known as Roger Vadim, whom Mr. Singer describes as a “minor league bohemian” at the time. Vadim contacted Brigitte, became her mentor and husband, and directed her in a number of films both before and after their divorce in 1957.

The Vadim-Bardot collaboration that made Brigitte an international film star and symbol of European sex appeal was the racy shocker, “And God Created Woman,” in which, Mr. Singer writes, Brigitte removed her clothing to a far greater extent than audiences were used to at the time. The movie opened in New York in 1957 with a huge poster of Miss Bardot in Times Square. Religious and other protests only fueled interest, and the film reaped a $4 million profit, a huge sum for the day, especially for a foreign-language film. Miss Bardot went on to a successful acting career that lasted into the early 1970s, sometimes working with top-of-the-line directors, including Jean-Luc Godard and Louis Malle. She was a world-wide celebrity, and in 1970, Charles de Gaulle did her the honor of naming her as the model for the busts of Marianne — the female symbol of France — that are displayed in every French city hall.

Mr. Singer, who teaches at Brock University in Ontario and has written extensively on French history and contemporary society, spends a good portion of the book taking us through Miss Bardot’s screen career, film by film. This is necessary, perhaps, in a biography of a movie star, but her life really became interesting when she retired from acting in 1973. BB, as she was known as a child and to her fans, did not retreat to a home in the country and spend the rest of her life giving dinner parties. She decided to do something that mattered, and, in a remarkable and courageous way she did, despite many obstacles. Now in her seventies, she is still doing it. Mr. Singer’s book would have been better with more details about the last three decades of her life, but what he does write is quite inspiring.

Because she took up with Vadim at such a young age, Miss Bardot did not even have a high school diploma, and in mid-life she took on the task of educating herself. She became an omnivorous reader of the classics and the best of contemporary literature. She also became a tireless advocate for the welfare and protection of animals. “Who has given Man,” she asked, “the right to exterminate, dismember, cut up, slaughter, hunt, chase, trap, lock up, martyr, enslave, and torture animals?” She launched the Fondation Brigitte Bardot (Google “Brigitte Bardot Foundation” to learn about it) and has traveled the globe on its behalf. She spends her days cleaning the kennels and taking her mangy crew of rescued dogs for walks. Brigitte Bardot is the real thing.

Miss Bardot had been a nationalist since her days as an actress. At the height of her career she spurned million-dollar offers from Hollywood so as to remain a French star, and her love of France only deepened after retirement. Beginning in the 1990s, she began to speak and write about the Islamization of France and the decline of French civility. It was in an article in the April 26, 1996 Le Figaro in which she first took a stand. Calling herself “a Frenchwoman of old stock,” she noted that both her father and grandfather had fought foreign invaders. “And now my country, France,” she continued, “my homeland, my land, is with the blessing of successive governments again invaded by a foreign, especially Moslem, over-population to which we pay allegiance. We must submit against our will to this Moslem overflow. From year to year, we see mosques flourish across France, while our church bells fall silent because of a lack of priests.”

She wrote with disgust of the ritual throat-slitting of millions of sheep by Muslims on feast days, calling such cruelties intolerable: “Could I be forced in the near future to flee my country which has turned into a bloody and violent country, to turn expatriate, to try and find elsewhere, by myself becoming an emigrant, the respect and esteem which we are alas refused daily?”

The next year, in light of a five-year Islamic insurgency in Algeria in which a number of French nationals, including monks, had their throats cut, she said: “They’ve slit the throats of women and children, of our monks, our officials, our tourists and our sheep. They’ll slit our throats one day and we’ll deserve it.” “A Muslim France, with a North African Marianne?” she asked. “Why not, at this point?”

Anti-racist groups sued her for “inciting racial hatred” and “provocation to hatred and discrimination,” and she was found guilty and fined in 1997, 1998 and 2000. By the end of the 1990s, some cities had smashed the Brigitte Bardot version of Marianne, and replaced it with one modeled on Catherine Deneuve.

Miss Bardot refused to be silenced. In 2003, she wrote a book called Un cri dans le silence (A Cry in the Silence), an instant best-seller that sold 120,000 copies in the first five days. The book reiterates Miss Bardot’s sadness about mass immigration and the Islamic influence. France is losing its “beauty and splendor,” she argues. “For twenty years,” she writes, “we have submitted to a dangerous and uncontrolled underground infiltration. Not only does it fail to give way to our laws and customs. Quite the contrary, as time goes by it tries to impose its own laws on us.” She decries “[a]ll those ‘youths’ who terrorize the population, rape young girls, train pit bulls to fight [and] spit on the police.”

Mr. Singer writes that Miss Bardot is an elegant writer — a real accomplishment for someone with a limited formal education — but Un cri dans le silence has not been translated into English. Amazon sells new and used copies, and there are four reader reviews. All give the book the top, five-star rating.

In a television interview to promote Un cri on the national station France 3, Miss Bardot criticized the authorities for letting illegal immigrants take over churches as protest sites, where they defecate in dark corners and turn sanctuaries into “veritable human pigsties.” She went on to raise eyebrows in certain circles by expressing disgust for sex-change operations paid for by the French national health service.

Once again, an anti-racist group attacked her. She was convicted of “inciting racial hatred,” and ordered to pay a fine of the equivalent of $6,000. During her trial, she told the court she opposes interracial marriage. Not surprisingly, Miss Bardot receives many letters from supporters who urge her to keep fighting.

Brigitte Bardot is among the most celebrated supporters of the French nationalist political party, the National Front. Its leader, Jean-Marie Le Pen, has called her “a great personality, a courageous woman, impartial, free, who says what she thinks, which in our country is rare in view of the dominant intellectual terrorism.” She is not a member of the National Front, though her current husband is. As she explained at the time of her marriage, “I married a man, not a party.”

Recently, Miss Bardot has thrown herself back into the campaign for animal welfare. On Nov. 20, 2006, when the European Commission proposed a total ban on commerce in dog and cat products, she was in the audience applauding. She explained that two million dogs and cats are slaughtered in Asia for fur, some of which finds its way into Europe.

In the last year or two, the former film star has said little in public about immigration, and much of the French press seems to have forgiven her so long as she sticks to animal rights. Backing down, however, is not in her nature. One of her most recent in-depth interviews was to journalist Jacques Guérin, who published a long account on Sept. 23, 2006. It was mostly about animal rights but also about her film career, her health, her loves, her disappointments — a typical celebrity interview. The only passage with an edge was the following:

Does she regret the excesses that led to a few brushes with the law, and gave the impression that she was sometimes not far from the positions of the National Front? ‘What excesses?’ she replies. ‘I take responsibility for what I said. It is true that I am on the right; I was reared that way. It is true that on certain subjects I may have expressed myself impulsively and therefore clumsily. But I regret nothing.’

Although I greatly admire Miss Bardot’s political courage and French patriotism, what most strongly impressed me about this book was her concern for animals. I will never look at a dog or a horse in quite the same way again. I read and think a lot about Western man, and the fate of our European heritage — what’s going to happen to us — and that is certainly important. But Miss Bardot’s biography reminded me that we are not the only ones who live and die and endure injustice and suffer, and that at least we can defend ourselves. After I finished the book, I went to the Humane Society near where I live, and gazed into the eyes of a black and white cat that looked back at me through the bars of its tiny cage.