Soaring Suicide Rate Is Up 33 Percent Since 1999 in Rural America

Natalie Rahhal, Daily Mail, November 29, 2018

Soaring suicide rate is blighting rural America: Deaths up 33% since 1999 – with twice as many in the country where people suffer in isolation

Natalie Rahhal, Daily Mail, November 29, 2018

Suicide rates in the US surged by nearly four percent between 2015 and 2016 alone and have risen 33 percent since 1999, new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention figures reveal.

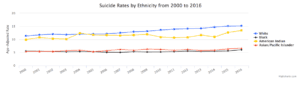

Across the country, hardly a life is untouched by suicide. It affects men and women of all ages races and income levels, claiming the lives of 14 out of every 100,000 Americans who died in 2017.

But rates, and particularly increases, are especially astonishing in some groups of Americans.

Driven by growing isolation and shrinking access to support, rates of suicide are now nearly twice as high in rural communities as they are in urban ones.

Though men continue to take take their own lives more frequently than women do, rate of suicide among women increased by 53 percent between 1999 and 2017 — climbing at twice the pace male suicides have.

Suicide remains the 10th leading cause of death in the US — a tragic figure that experts say won’t change without hard — and expensive research.

The high-profile suicides of late celebrities Kate Spade and Anthony Bourdain in the past year, as well as the controversy that follows Netflix’s 13 Reasons Why have drawn suicide into the public eye, perhaps more than ever.

This might suggest the dissipation of stigma — thought to be a significant risk factor — but it certainly hasn’t stopped rates of suicide from creeping steadily upward in the US.

In 1999, 17.8 out of every 100,000 men’s deaths were suicides, as were every four out of 100,000 women’s deaths.

Last year, those numbers had increased to 22.4 and 6.1 per 100,000 deaths, respectively.

We might be seeing suicide more, but we don’t understand it much better.

The pathology of suicide is far from uniform and difficult to study for both practical and ethical standpoints.

But we do know some risk factors that drive higher rates among some groups than others.

For example, while women have historically attempted suicide at higher rates, men have completed the act of taking their own lives more frequently.

As Dr April Foreman, a psychologist who serves the Veterans’ Suicide Prevention Network, and a member of the American Association of Suicidology’s board of directors puts it: ‘Women attempt more often but men pick things that will kill you faster.’

Research on the ‘why’ of this tendency remains thin, but last year’s data suggests an alarming shift.

Speculatively, Dr Foreman says that it ‘looks like women are attempting more often or choosing more lethal means.’

This many mean that there are new or different strains or stressors affecting women and/or they have increased access to more lethal means, but we don’t yet have the data to know for sure.

Access to lethal means is often suggested as one significant factor — but hardly the only one — contributing to the high rates of suicide in rural America.

Numerous studies have shown that suicide is more prevalent where guns are too.

But isolation, economics and ever-receding access to health care and suicide crisis services play critical roles in suicide rates as well — and suicide goes hand-in-hand with the opioid epidemic.

Dr Bart Andrews, a psychologist with Telehealth and Home/Community Services at Behavioral Health Response notes that there is an ‘overlap between the opioid epidemic and the suicide crisis.’

‘Where the economy has changed dramatically and is faltering you see opioids used a lot.’

Dr Foreman adds: ‘its pretty easy to get opioids, but not mental health care’ in rural areas.

Dr Andrews calls our current economic a ‘tale of two countries’ that has become a perfect storm for suicidality in rural America.

He says that suicides increased after the 2008 economic collapse. So it might stand to reason that the current economic boom is driving them down — but not so, says Dr Andrews.

While urban areas boom, rural communities ‘experience population loss as those that can get jobs do get jobs and get out. The folks that stay have a weakened community and don’t have particularly good care,’ he says.

And that population leaves growing gaps between people in rural areas, feeding feelings of isolation.

‘One of the most protective things for people who are suicidal is to be around people,’ says Dr Foreman.

As that resource is disappearing, so is funding for regional and state suicide crisis hotlines, and the hotlines themselves.

Meanwhile, Dr Andrews notes that suicide prevention training is only required of primary care doctors in 10 states — and most doctors are totally unfamiliar with the skill set.

‘Many suicidal people don’t ever hit the behavioral health system or reach out for help,and when they do, we don’t do a good job with the people who are hitting the system at a regional level, and we don’t have a scaleable way to do suicide prevention on a national level,’ Dr Andrews says.

[Click on the image to enlarge it.]