How They Got the Vote

Thomas Jackson, American Renaissance, August 2001

Alexander Keyssar, The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States, Basic Books, 2000, 467 pp.

Except for occasional backtracking, the history of the franchise in the United States has been one of constant expansion. In colonial times and in most areas after the Revolution, only white property-owners, age 21 or over could vote. Every one of those restrictions has since been abolished, and now any non-felon age 18 or over can vote. Why? What prompted people who had the vote to give it to those who did not? Alexander Keyssar, who is a professor of history and public policy at Duke University, tells us this is the first book ever written about that process. Needless to say, Prof. Keyssar is delighted things turned out as they did and thinks they should go further still. However, in this well-researched account he manages most of the time to keep a leash on his liberal impulses and even occasionally to outline some of the arguments made to oppose expanding the franchise.

Property

Part of the colonial legacy was a conviction that only men of property had enough independence of mind and a sufficient stake in society to be trusted with the vote. Servants, women, and the poor were too dependent on the authority of others. There was also a broad conviction that opportunities were so great in the colonies that only the shiftless failed to acquire property. In the late colonial period, perhaps just under 60 percent of white men owned property and could vote.

The Revolution required every state to establish a new government and to reopen the question of whether the vote was a right or a privilege. Given the radical sentiment of the times, it is surprising that only one state — Vermont — abolished the property qualification. The drafters of the federal Constitution wanted to let only landholders vote in federal elections, but did not write in a property requirement for fear it might prevent ratification. The federal government left the determination of voter qualifications entirely to the states.

There were contradictions in arguments both for and against giving the vote to the propertyless. To say voting was a natural right regardless of wealth opened the door to giving it to women and blacks, which almost no one wanted to do. As John Adams put it in 1776:

Depend upon it, Sir, it is dangerous to open so fruitful a source of controversy and altercation as would be opened by attempting to alter the qualifications of voters; there will be no end of it. New claims will arise; women will demand the vote; lads from twelve to twenty-one will think their rights not enough attended to; and every man who has not a farthing, will demand an equal voice with any other in all acts of state. It tends to confound and destroy all distinctions, and prostrate all ranks to one common level.

Supporters of the property requirement also contradicted themselves. They said the propertyless would vote like sheep, as instructed by their employers, but also that they would vote selfishly against the established interests of their betters.

The process of seceding from England loosened voter qualifications in some states but tightened them in others. Before independence, Catholics could not vote in five states, and Jews were disfranchised in four; after independence they could vote everywhere. Massachusetts, however, had a stricter property requirement after the Revolution than before. The initial republican impetus did not have the universally leveling effect one might have expected.

However, as Prof. Keyssar points out, war itself tends to broaden the franchise, and this was true of both the Revolution and the War of 1812. Propertyless soldiers circulated petitions demanding the vote, and the upper classes wondered whether disfranchised men would shoulder arms with sufficient enthusiasm. Ben Franklin was among those who argued that a propertyless man with the vote was a better ally than one without it.

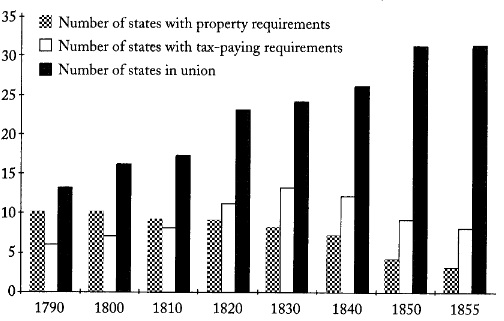

Many states relaxed or abolished property requirements during this period, and none of the new states admitted after 1790 had the requirement in its original constitution. Prof. Keyssar notes that in the early years, many people were particularly loathe to give the vote to landless urban workers. Not a few states dropped the property requirement on the mistaken assumption that in so vast a country as the United States, most men would always be farmers, and that there would never be an urban proletariat.

Virginia was the last state to have a property requirement for all electors, abolishing it only in the mid 1850s. By this time the only such qualifications targeted specific groups: New York had a property requirement only for blacks and Rhode Island had one only for the foreign-born.

After the Civil War, when it became clear industrialization had produced the very urban proletariat agrarians had feared, there was a revival of sentiment against letting all men vote. Prof. Keyssar quotes Chancellor Kent of New York, who decried “the tendency in the poor to covet and to share the plunder of the rich; in the debtor to relax or avoid the obligation of contracts; in the majority to tyrannize over the minority, and trample down their rights; in the indolent and the profligate to cast the whole burthen of society upon the industrious and the virtuous.” Kent concluded that “the poor man’s interest is always in opposition to his duty,” and lamented that there was no way by which to take back the vote from the propertyless.

The arrival of large numbers of immigrants in the 1870s and 1880s also dampened enthusiasm for manhood suffrage. In words no less relevant today, America’s most celebrated historian, Francis Parkman, complained in 1878 about “restless workmen, foreigners for the most part, to whom liberty means license and politics means plunder, to whom the public good is nothing and their own most trivial interests everything, who love the country for what they can get out of it . . . .” In his view, the masses “want equality more than they want liberty.”

A variant of the property requirement is exclusion of paupers from the vote. Americans have traditionally thought anyone on public relief forfeits his say in government, but the Great Depression cast doubt on this principle. Suddenly there were so many responsible, hard-working men on relief it was difficult to deny them the vote. The Supreme Court finally did away with all pauper exclusions in 1966, at the same time it abolished the poll tax. These activist decisions, which were part of a concerted move to federalize all voting laws, struck down the final vestiges of what had, for centuries, been a central qualification for the franchise: property.

Blacks

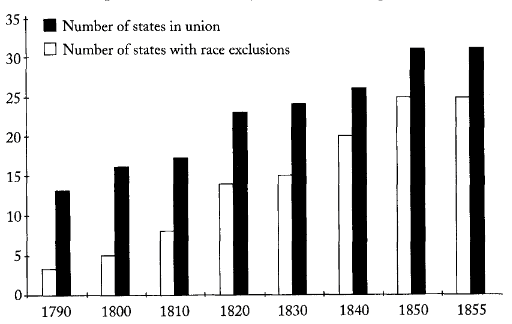

At various times during the colonial or early post-revolutionary period, free blacks could vote in North Carolina, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Vermont. After independence, three states quickly took back the franchise from blacks — New Jersey, Maryland, and Connecticut — and New York effectively cut off all but a handful of black voters by passing a property requirement for blacks only. Every state that entered the union after 1819 denied blacks the franchise, and in 1855 they could vote only in Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, and Rhode Island. Together, these states held only four percent of the nation’s blacks. The federal government prohibited free Negroes from voting in the territories it controlled, and in 1857 the Supreme Court ruled that blacks, free or slave, could not be citizens of the United States, though they might be citizens of states.

When new states joined the union, it was common at least to discuss the possibility of letting blacks vote, and from time to time referenda and constitutional conventions considered the question. The proposals always lost, usually by wide margins. At the Indiana convention of 1850, one delegate even offered an amendment “that all persons voting for negro suffrage shall themselves be disfranchised.” Many people in the north argued that giving blacks the vote would attract freedmen and runaways, and most whites wanted nothing to do with blacks.

The Civil War appears to have changed the thinking of some northerners about race, if only because war passions made it easier to oppose the practices of the enemy. The 13th amendment, ratified in 1865, emancipated the slaves, and the 14th amendment set out penalties for states that disfranchised voters on the basis of race. Representation in Congress and the electoral college was to be reduced by the proportion of the electorate denied the vote because of race. This was obviously directed at the south; northern and western states with few blacks could disfranchise them at little cost. The amendment is significant in that although it penalized racial discrimination, it accepted it in principle.

The ratification history of the 15th amendment — which in 1870 forbade withholding the vote on racial grounds — is instructive. It passed easily only in New England, where there were few blacks. It was ratified in southern legislatures, but by the same fraudulent procedure used to ratify the other Civil War amendments. Reconstruction governments were unrepresentative of the white majority, and for four former Confederate states, ratification was a condition for readmission to the Union.

In the Western part of the country, there was much opposition to the amendment for fear it would give the vote to the Chinese. Although Rhode Island had already let blacks vote, it barred the Irish from the polls. Ratification was long delayed, and nearly failed for fear the amendment would give the Irish “race” the vote. Prof. Keyssar points out that the amendment did not reflect a desire for racial equality so much as political calculation and zeal for punishing the south. Republicans were certain most blacks would vote for their party, and wanted to expand their constituency in the south, while in the north there were not enough black voters to cause trouble.

With Redemption, or the overthrow of Reconstruction governments, southern whites found many ways to minimize the black vote. One was simply to throw out returns from black areas. When, in 1884, Grover Cleveland became the first Democratic president since the Civil War, Republicans complained that the narrow margin of victory would have been reversed if the heavily-Republican southern black vote had not been ignored.

Soon southern states had regulations that did not explicitly disfranchise blacks but had the same effect: literacy tests, residency requirements, poll taxes, and complex registration schemes. In some states, white men were “grandfathered,” or exempted from these requirements if they had served in the Confederate army or if their ancestors had voted in the 1860s. Elsewhere, middle-class whites were happy to disfranchise “ignorant, incompetent and vicious” white men along with blacks.

Whites made no secret of their intentions. As Carter Glass explained at Virginia’s constitutional convention of 1901-02: “Discrimination! Why, that is precisely what we propose. That, exactly, is what this Convention was elected for — to discriminate to the very extremity of permissible action under the limitations of the Federal Constitution, with a view to the elimination of every negro voter who can be gotten rid of . . . .”

Many were gotten rid of. In 1896 in Louisiana, there were still 130,000 registered black voters; by 1904, new restrictions had reduced that number to only 1,342. After Mississippi passed new voting laws in 1890, there were only 9,000 registered blacks out of an eligible population of 147,000.

Even when blacks managed to register, the white Democratic primary meant their votes meant nothing. In many southern states, the Republican party — the party of Lincoln — had no white following at all. The real contest took place in the Democratic primary, with the general election a mere formality. Many state Democratic parties declared themselves private clubs open only to whites. This way the primary vote, which was all that mattered, excluded blacks.

The north quickly lost interest in policing southern whites, and there were only sporadic calls to exercise the 14th amendment’s provisions to limit representation in Congress and the electoral college. The Supreme Court went on to uphold every major disfranchisement technique.

But it was, of course, the Supreme Court that eventually dismantled these techniques. Although it had ruled in 1935 that white primaries were Constitutional, a Supreme Court composed almost exclusively of Roosevelt New Dealers reversed course in 1944. This was the beginning of a complete federal takeover of state election laws that included the Voting Rights Act of 1965, its expansion to include “language minorities,” and the more recent struggle over “majority-minority” districts. For Prof. Keyssar, the federal triumph is best symbolized by the fact that in 1960 many Puerto Ricans were kept from the polls by English-language literacy tests, but by 1976 they got ballots in Spanish.

Why, after some 80 years of paying no attention to blacks, did Congress and the Supreme Court suddenly insist on ensuring their voting rights? Prof. Keyssar suggests that in the competition with Soviet Communism for world leadership, racial discrimination was the Achilles heel of American democracy. There may be something to this, but anti-racism was just one part of a liberal/socialist revolution that left nothing unchanged. Competition with Communism hardly required the sexual revolution, the decline of good manners, women’s “liberation,” hippies, or the relentless expansion of federal power. Anti-racism was one more frantic act of a culture devouring itself, not a way to prove we were as good as the Soviets.

Prof. Keyssar is more interesting when he notes the ways in which whites distinguished between blacks and Indians. Even in the earliest days, Indians were only rarely barred from the polls on racial grounds; they were admitted if they were civilized and paid taxes. The 14th amendment granted Indians citizenship and the right to vote in federal elections, but an 1884 Supreme Court decision ruled that the amendment’s grant of citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States” did not apply to Indians born on tribal lands. Nevertheless, the policy was to encourage assimilation, and in 1924 — at a time when blacks were routinely kept from the polls in the south — Congress declared all Indians to be citizens and voters.

Women

Few people know that women were voting in American elections long before the 19th amendment was ratified in 1920. The original constitution of New Jersey let women vote, though the state took this right away in 1807. Here and there, propertied widows and unmarried women could vote in school-related elections, and women could vote in some Western states long before the 19th amendment.

The movement for women’s suffrage began in earnest in 1848 and was closely associated with abolitionists. Many early suffragettes assumed women would get the vote along with blacks, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, one of the movement’s hallowed founders, thought women should take precedence: “I would not trust him [the colored man] with all my rights; degraded and oppressed himself, he would be more despotic with the governing power than even our Saxon rulers are.” However, extending the vote to women would have brought to Republicans none of the political advantages of extending it to blacks, and the 15th amendment severed any connection between the two movements. Still, the abolition and votes-for-blacks campaigns were important training grounds for suffragettes, who built up increasingly powerful local movements.

The debate took many turns. Sometimes women argued they should vote because they were just as intelligent and sensible as men — essentially the same as men. They also argued that women should vote because women were different from men — more peaceable and caring. One suffragette even proposed that government was akin to housekeeping, and that natural housekeepers would be particularly good at it. Curiously, the opposing view was that the purity of women would be degraded by involving them in the dirty business of politics. It was also common to argue that voting would change sex roles and destroy the family. The liquor industry opposed votes-for-women for fear women would vote for prohibition. Rarely does anyone appear to have warned of what actually happened: that women would vote differently from men: more socialst.

The thin edge of the wedge was the west. Wyoming territory gave women the vote in 1869 and did not take it back on becoming a state in 1889. Utah did the same in 1870 and 1896. Idaho and Colorado gave women the vote in the mid-1890s, at a time when eastern states were routinely defeating suffragette proposals. It is common to attribute this to some uniquely Western broad-mindedness, but Prof. Keyssar supplies the corrective: Western states had large numbers of bachelor ranch hands and laborers. The propertied classes, who set the rules, were more likely to be married, and they gave their wives and daughters the vote in the hope this would counter the influence of landless drifters.

By the 1870s and 1880s, a common suffragette argument was that giving (white) women the vote would likewise counter the votes of blacks, Chinese, aliens, and other undesirables. In the south, activists argued that “Anglo-Saxon women” were “the medium through which to retain the supremacy of the white race over the African.” Southern women strongly supported literacy tests and poll taxes. However, some southern whites thought giving women the vote would make it harder to keep it from blacks. As a senator from Mississippi pointed out shortly after the turn of the 20th century, “We are not afraid to maul a black man over the head if he dares to vote, but we can’t treat women, even black women, that way.”

After about 1910, votes for women became associated with socialists and the left, and between 1910 and 1913 activists got the help of trade unions to secure women’s suffrage in California, Arizona, Kansas, Oregon, Illinois, and Washington.

By the First World War, suffragettes had a noisy, nation-wide movement. By then, there were so many women voting in so many states it became difficult for any party to take a position against it; it could be punished at the polls wherever women already voted. When the United States entered the war, women argued that although President Wilson claimed to be fighting for democracy he denied it to half the population. Women also helped on the home front and activists threatened to down tools if they did not get the vote. The 19th amendment passed the House in 1918 and the Senate in 1919. By then, suffragettes had well-oiled machinery in more than enough states for quick ratification.

Although property, sex, and race have been the main obstacles to voting, Prof. Keyssar approvingly describes the other barriers that have fallen. The 1972 amendment that lowered the voting age to 18 was yet another enthusiasm of the times, but the Vietnam-driven idea that draftees should be able to vote was not without opposition. Congressman Emanuel Celler of New York said: “To my mind the draft age and the voting age are as different as chalk and cheese. The thing called for in a soldier is uncritical obedience, and that is not what you want in a voter.” He added: “[The years of young adulthood] are rightfully the years of rebellion rather than reflection. We will be doing a grave injustice to democracy if we grant the vote to those under twenty-one.”

For Prof. Keyssar, there is still one piece of unfinished business in the glorious work of expanding the franchise. Most states still keep felons out of the voting booth, and Prof. Keyssar is distressed to find that they are disproportionately black. He has swallowed the view that this reflects “racism” rather than crime rates, and looks to the day when released jail-birds can vote.

In what is inevitably an approving account of much progress, Prof. Keyssar does strike a warning about low rates of voter participation. In the 1830s and 1840s, he tells us, participation reached 80 percent, but today even a presidential election can draw only 50 percent of voters, and local elections only 20 to 25. Prof. Keyssar does not seem to realize that the very thing he celebrates — expanding the rolls — probably explains this. Blacks, women, and the propertyless vote less frequently than white men of means. It would be interesting to know the current voter participation rates of people who would have met the restrictions still in place in the 1830s.

Another question Prof. Keyssar completely ignores is the political effect of expanding the franchise. Blacks do not vote the same as whites, nor do women vote like men. What is the nature of these differences, and how do they effect elections? Prof. Keyssar no doubt approves of the effects, but to ignore them is almost to miss the point of writing his book. Women, blacks, and beggars presumably wanted the vote because their vote would not be the same as those who already voted. Was what they wanted good for the country? Was it good even for them?

Prof. Keyssar seems to think expanding the franchise in every direction is so obviously good there is not need to study its consequences. It is precisely because it had consequences that people opposed it. Did they have good reasons? It is with the characteristic arrogance of his times that Prof. Keyssar does not even consider these questions.