Black Mothers Keep Dying After Giving Birth. Shalon Irving’s Story Explains Why

Nina Martin, NPR, December 7, 2017

{snip}

At 36, Shalon had been part of their elite ranks — an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the pre-eminent public health institution in the U.S. There she had focused on trying to understand how structural inequality, trauma and violence made people sick. “She wanted to expose how people’s limited health options were leading to poor health outcomes,” said Rashid Njai, her mentor at the agency. “To kind of uncover and undo the victim-blaming that sometimes happens where it’s like, ‘Poor people don’t care about their health.’ ” Her Twitter bio declared: “I see inequity wherever it exists, call it by name, and work to eliminate it.”

Much of Shalon’s research had focused on how childhood experiences affect health later on — examining how kids’ lives went off track, searching for ways to make them more resilient. Her discovery in mid-2016 that she was pregnant with her first child had been unexpected and thrilling.

Then the unthinkable happened. Three weeks after giving birth, Shalon collapsed and died from complications of high blood pressure.

{snip}

Racial disparity across incomes

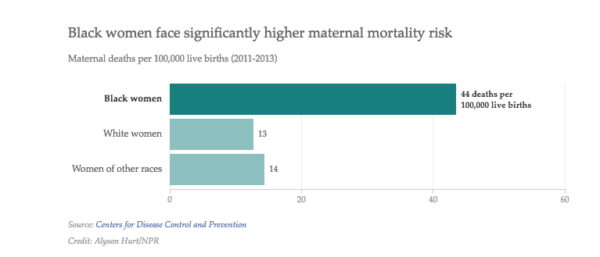

In recent years, as high rates of maternal mortality in the U.S. have alarmed researchers, one statistic has been especially concerning. According to the CDC, black mothers in the U.S. die at three to four times the rate of white mothers, one of the widest of all racial disparities in women’s health. Put another way, a black woman is 22 percent more likely to die from heart disease than a white woman, 71 percent more likely to perish from cervical cancer, but 300 percent more likely to die from pregnancy- or childbirth-related causes. In a national study of five medical complications that are common causes of maternal death and injury, black women were two to three times more likely to die than white women who had the same condition.

That imbalance has persisted for decades, and in some places, it continues to grow. In New York City, for example, black mothers are 12 times more likely to die than white mothers, according to the most recent data; in 2001-2005, their risk of death was seven times higher. Researchers say that widening gap reflects a dramatic improvement for white women but not for blacks.

The disproportionate toll on African-Americans is the main reason the U.S. maternal mortality rate is so much higher than that of other affluent countries. Black expectant and new mothers in the U.S. die at about the same rate as women in countries such as Mexico and Uzbekistan, the World Health Organization estimates.

What’s more, even relatively well-off black women like Shalon Irving die and nearly die at higher rates than whites. Again, New York City offers a startling example: A 2016 analysis of five years of data found that black, college-educated mothers who gave birth in local hospitals were more likely to suffer severe complications of pregnancy or childbirth than white women who never graduated from high school.

The fact that someone with Shalon’s social and economic advantages is at higher risk highlights how profound the inequities really are, said Raegan McDonald-Mosley, the chief medical director for Planned Parenthood Federation of America, who met her in graduate school at Johns Hopkins University and was one of her closest friends. “It tells you that you can’t educate your way out of this problem. You can’t health care-access your way out of this problem. There’s something inherently wrong with the system that’s not valuing the lives of black women equally to white women.”

For much of American history, these types of disparities were largely blamed on blacks’ supposed susceptibility to illness — their “mass of imperfections,” as one doctor wrote in 1903 — and their own behavior. But now many social scientists and medical researchers agree, the problem isn’t race but racism.

The systemic problems start with the type of social inequities that Shalon studied — differing access to healthy food and safe drinking water, safe neighborhoods and good schools, decent jobs and reliable transportation.

Black women are more likely to be uninsured outside of pregnancy, when Medicaid kicks in, and thus more likely to start prenatal care later and to lose coverage in the postpartum period. They are more likely to have chronic conditions such as obesity, diabetes and hypertension that make having a baby more dangerous. The hospitals where they give birth are often the products of historical segregation, lower in quality than those where white mothers deliver, with significantly higher rates of life-threatening complications.

Those problems are amplified by unconscious biases that are embedded in the medical system, affecting quality of care in stark and subtle ways. In the more than 200 stories of African-American mothers that ProPublica and NPR have collected over the past year, the feeling of being devalued and disrespected by medical providers was a constant theme.

{snip}

In a survey conducted this year by NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, 33 percent of black women said that they personally had been discriminated against because of their race when going to a doctor or health clinic, and 21 percent said they have avoided going to a doctor or seeking health care out of concern they would be racially discriminated against.

{snip}

But it’s the discrimination that black women experience in the rest of their lives — the double whammy of race and gender — that may ultimately be the most significant factor in poor maternal outcomes.

“It’s chronic stress that just happens all the time — there is never a period where there’s rest from it. It’s everywhere; it’s in the air; it’s just affecting everything,” said Fleda Mask Jackson, an Atlanta researcher who focuses on birth outcomes for middle-class black women.

It’s a type of stress for which education and class provide no protection. “When you interview these doctors and lawyers and business executives, when you interview African-American college graduates, it’s not like their lives have been a walk in the park,” said Michael Lu, a longtime disparities researcher and former head of the Maternal and Child Health Bureau of the Health Resources and Services Administration, the main federal agency funding programs for mothers and infants. “It’s the experience of having to work harder than anybody else just to get equal pay and equal respect. It’s being followed around when you’re shopping at a nice store, or being stopped by the police when you’re driving in a nice neighborhood.”

An expanding field of research shows that the stress of being a black woman in American society can take a physical toll during pregnancy and childbirth.

Chronic stress “puts the body into overdrive,” Lu said. “It’s the same idea as if you keep gunning the engine, that sooner or later you’re going to wear out the engine.”

As women get older, birth outcomes get worse. … If that happens in the 40s for white women, it actually starts to happen for African-American women in their 30s.

Arline Geronimus, a professor at the University of Michigan School of Public Health, coined the term “weathering” for stress-induced wear and tear on the body. Weathering “causes a lot of different health vulnerabilities and increases susceptibility to infection,” she said, “but also early onset of chronic diseases, in particular, hypertension and diabetes” — conditions that disproportionately affect blacks at much younger ages than whites. Her research even suggests it accelerates aging at the molecular level; in a 2010 study Geronimus and colleagues conducted, the telomeres (chromosomal markers of aging) of black women in their 40s and 50s appeared 7 1/2 years older on average than those of whites.

Weathering has profound implications for pregnancy, the most physiologically complex and emotionally vulnerable time in a woman’s life. Stress has been linked to one of the most common and consequential pregnancy complications, preterm birth. Black women are 49 percent more likely than whites to deliver prematurely (and, closely related, black infants are twice as likely as white babies to die before their first birthday). Here again, income and education aren’t protective.

The repercussions for the mother’s health are also far-reaching. Maternal age is an important risk factor for many severe complications, including pre-eclampsia, or pregnancy-induced hypertension. “As women get older, birth outcomes get worse,” Lu said. “If that happens in the 40s for white women, it actually starts to happen for African-American women in their 30s.”

This means that for black women, the risks for pregnancy start at an earlier age than many clinicians — and women — realize, and the effects on their bodies may be much greater than for white women. In Geronimus’ view, “a black woman of any social class, as early as her mid-20s should be attended to differently.”

{snip}

Sporadic postpartum care

Until recently, much of the discussion about maternal mortality has focused on pregnancy and childbirth. But according to the most recent CDC data, more than half of maternal deaths occur in the postpartum period, and one-third happen seven or more days after delivery. For American women in general, postpartum care can be dangerously inadequate — often no more than a single appointment four to six weeks after going home.

“If you’ve had a cesarean delivery, if you’ve had pre-eclampsia, if you’ve had gestational diabetes or diabetes, if you go home on an anticoagulant — all those women need to be seen significantly sooner than six weeks,” said Haywood Brown, a professor at Duke University medical school. Brown has made reforming postpartum care one of his main initiatives as president of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The dangers of sporadic postpartum care may be particularly great for black mothers. African-Americans have higher rates of C-section and are more than twice as likely to be readmitted to the hospital in the month following the surgery. They have disproportionate rates of hypertensive disorders and peripartum cardiomyopathy (pregnancy-induced heart failure), two leading killers in the days and weeks after delivery. They’re twice as likely as white women to have postpartum depression, which contributes to poor outcomes, but they are much less likely to receive mental health treatment.

If they experience discrimination or disrespect during pregnancy or childbirth, they are more likely to skip postpartum visits to check on their own health (they do keep pediatrician appointments for their babies). In one study published earlier this year, two-thirds of low-income black women never made it to their doctor visit.

Meanwhile, many providers wrongly assume that the risks end when the baby is born — and that women who came through pregnancy and delivery without problems will stay healthy. In the case of black women, providers may not understand their true biological risks or evaluate those risks in a big-picture way. “The maternal experience isn’t over right at delivery. All of the due diligence that gets applied during the prenatal period needs to continue into the postpartum period,” said Eleni Tsigas, executive director of the Preeclampsia Foundation.

All of the due diligence that gets applied during the prenatal period needs to continue into the postpartum period.

It’s not just doctors and nurses who need to think differently. Like a lot of expectant mothers, Shalon had an elaborate plan for how she wanted to give birth, even including what she wanted her surgical team to talk about (nothing political) and who would announce the baby’s gender (her mother, not a doctor or nurse). But like most pregnant women, she didn’t have a postpartum care plan. “It was just trusting in the system that things were gonna go OK,” Wanda said. “And that if something came up, she’d be able to handle it.”

{snip}

C-sections have much higher complication rates than vaginal births. {snip}