Hoping for Asylum, Migrants Strain U.S. Border

Julia Preston, New York Times, April 11, 2014

Border Patrol agents in olive uniforms stood in broad daylight on the banks of the Rio Grande, while on the Mexican side smugglers pulled up in vans and unloaded illegal migrants.

The agents were clearly visible on that recent afternoon, but the migrants were undeterred. Mainly women and children, 45 in all, they crossed the narrow river on the smugglers’ rafts, scrambled up the bluff and turned themselves in, signaling a growing challenge for the immigration authorities.

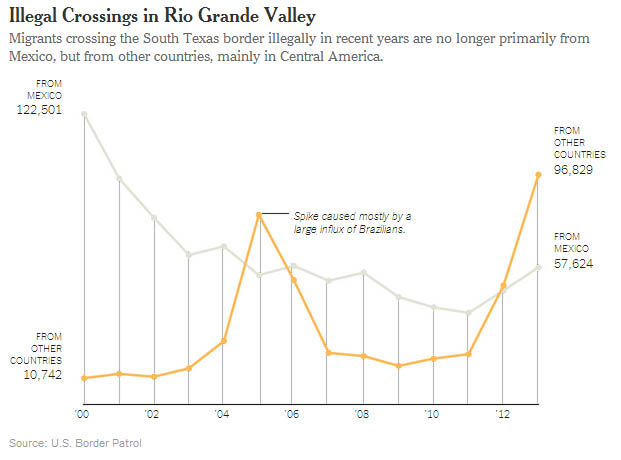

After six years of steep declines across the Southwest, illegal crossings have soared in South Texas while remaining low elsewhere. The Border Patrol made more than 90,700 apprehensions in the Rio Grande Valley in the past six months, a 69 percent increase over last year.

The migrants are no longer primarily Mexican laborers. Instead they are Central Americans, including many families with small children and youngsters without their parents, who risk a danger-filled journey across Mexico. Driven out by deepening poverty but also by rampant gang violence, increasing numbers of migrants caught here seek asylum, setting off lengthy legal procedures to determine whether they qualify.

The new migrant flow, largely from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, is straining resources and confounding Obama administration security strategies that work effectively in other regions. {snip}

With detention facilities, asylum offices and immigration courts overwhelmed, enough migrants have been released temporarily in the United States that back home in Central America people have heard that those who make it to American soil have a good chance of staying.

“Word has gotten out that we’re giving people permission and walking them out the door,” said Chris Cabrera, a Border Patrol agent who is vice president of the local of the National Border Patrol Council, the agents’ union. “So they’re coming across in droves.”

{snip}

{snip}

The new migrants head for South Texas because it is the shortest distance from Central America. Many young people ride across Mexico on top of freight trains, jumping off in Reynosa.

The Rio Grande twists and winds, and those who make it across can quickly hide in sugar cane fields and orchards. In many places it is a short sprint to shopping malls and suburban streets where smugglers pick up migrants to continue north.

{snip}

But whereas Mexicans can be swiftly returned by the Border Patrol, migrants from noncontiguous countries must be formally deported and flown home by other agencies. Even though federal flights are leaving South Texas every day, Central Americans are often detained longer.

Women with children are detained separately. But because the nearest facility for “family units” is in Pennsylvania, families apprehended in the Rio Grande Valley are likely to be released while their cases proceed, a senior deportations official said.

Minors without parents are turned over to the Department of Health and Human Services, which holds them in shelters that provide medical care and schooling and tries to send them to relatives in the United States. The authorities here are expecting 35,000 unaccompanied minors this year, triple the number two years ago.

Under asylum law, border agents are required to ask migrants if they are afraid of returning to their countries. If the answer is yes, migrants must be detained until an immigration officer interviews them to determine if the fear is credible. If the officer concludes it is, the migrant can petition for asylum. An immigration judge will decide whether there is a “well-founded fear of persecution” based on race, religion, nationality, political opinion or “membership in a particular social group.”

Immigration officials said they had set the bar intentionally low for the initial “credible fear” test, to avoid turning away a foreigner in danger. In 2013, 85 percent of fear claims were found to be credible, according to federal figures.

As more Central Americans have come, fear claims have spiked, more than doubling in 2013 to 36,026 from 13,931 in 2012.

The chances have not improved much to win asylum in the end, however. In 2012, immigration courts approved 34 percent of asylum petitions from migrants facing deportation–2,888 cases nationwide. Many Central Americans say they are fleeing extortion or forced recruitment by criminal gangs. But immigration courts have rarely recognized those threats as grounds for asylum.

Yet because of immense backlogs in the courts–with the average wait for a hearing currently at about 19 months–claiming fear of return has allowed some Central Americans to prolong their time in the United States.

{snip}