The White Masai, Part I

Anastasia Katz, American Renaissance, July 25, 2025

Subscribe to future audio versions of AmRen articles here.

The White Masai, Harper Collins, 2006, 307 pages, $28.96.

(Originally published in Germany in 1998 by Al Verlag GmbH Munich as Die Weisse Massai.)

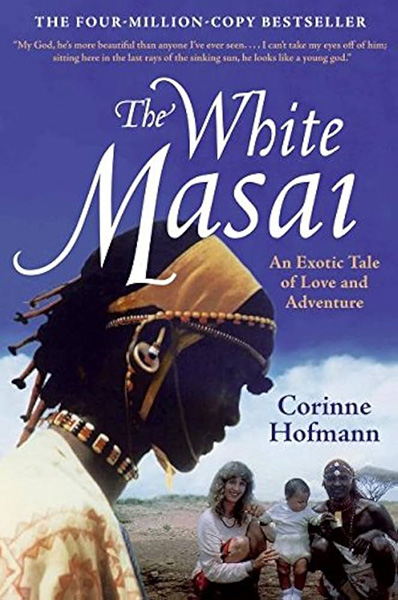

The book The White Masai is a memoire by Corinne Hofmann, a white Swiss woman who married a primitive African man and tried to live in his world. While others around her, especially blacks, had no illusions that their marriage was a fool’s errand, the author had a naïve “love conquers all” attitude, and she spent three-and-a-half years desperately trying to live out the fairy tale.

The book explores the perils of life in sub-Saharan Africa, both from nature and from people. In vivid detail, it describes the type of society an African tribe formed with minimal exposure to European influence. Corinne’s story is a perfect case study showing that racial differences can be so vast that no amount of love and devotion can overcome them.

How they met

In the late 1980s, Corinne Hofmann owned a clothing and bridal shop in Switzerland. She lived with her boyfriend, Marco, and by the time the couple left for a vacation in Kenya, friends were asking if they might get engaged soon.

The pair booked a stay in the coastal city Mombasa. On their first visit to the beach, Corinne wished she could live there. The next evening, after a day of sight-seeing, they took a ferry on the way back to their hotel and spotted a Masai man among the mostly black crowd on the boat.

At that time, there were fewer than 400,000 Masai; today, there are about 1.2 million. The black Kenyans who adopted Western customs looked down on the Masai and discriminated against them. A black tour bus driver had described them as “the last uncivilized people in Kenya” and said that they were trouble.

Corinne fell in love at first sight. The man was a warrior — a young man who has been circumcised in a rite-of-passage ceremony and is responsible for protecting his community and its livestock. He was six-foot-six and was dressed in a short red loincloth, sandals made from car tires, and lots of jewelry. He wore a pearl headband that held a large mother-of-pearl button to his forehead, and several bracelets and necklaces. His face, neck, and chest were painted. He had long braided hair that had been dyed with red ochre. Corinne admired his “elegantly proportioned” face and thought he looked like “a young god.” She wanted to talk to him but she spoke German. Kenya’s main languages are Swahili and English. The Masai speak Maa.

When they got off the ferry, Corinne and Marco had trouble finding the bus back to their hotel, and the Masai helped them get on the right bus. Corinne thought he was a “beautiful human being,” and wrote that his odor gave her “an erotic charge.” She stared at him for the whole bus ride. Marco noticed and was embarrassed.

Corinne was dying to see the Masai warrior again, so she convinced Marco to leave the resort and visit an outdoor disco that let in Masai people. While Marco sat drinking beer, Corinne danced herself sweaty several nights in a row, until “her” Masai finally showed up. She got Marco to buy him a beer to thank him for helping them.

His name was Lketinga Leparmorijo. He asked Marco, “Why you not dance with your wife?” Corinne replied, “No, only boyfriend, no married!” and she led him onto the dance floor. “We dance, me European-style, him more sort of hopping up and down like in a tribal dance.”

Lketinga invited the couple to meet his friends the following night. Corinne was excited and Marco agreed to go along; he thought Corinne was just having a silly infatuation that would end when they got back to Switzerland.

The next evening, Lketinga took them on a 20-minute walk through the jungle, with monkeys swinging in the trees, to a village of five round huts with straw roofing. He introduced Corinne to his Masai friend Priscilla, who served everyone chai tea. The Masai drank it all day, even in the hottest weather, and it was common courtesy to offer guests a cup. Priscilla spoke English well, but Lketinga’s English was poor. Marco knew enough to converse, and they had a pleasant visit. They made plans to meet at the disco again.

A male friend of Lketinga’s found Corinne at the disco and told her Lketinga couldn’t come because he was in jail. He had gone to a beach where Masai were not permitted and got into a fight, swinging his rungu club at another black man.

Corinne decided to use her last day in Kenya to find Lketinga and bail him out. It took all day to find him, and then the jail wouldn’t process the bail because it was a holiday. Corinne got permission to visit Lketinga for 10 minutes and she gave him money. She got back to the hotel so late that Marco was just happy to see her alive.

Corinne broke up with Marco on the flight home, telling him that she would move out, and eventually move to Kenya. “I can’t explain, even to myself, what secret magic there is about this man,” she wrote. “If anyone had told me two weeks ago, I would fall in love with a Masai warrior, I would have laughed out loud. Now my life had been thrown into chaos.”

The courtship

For the next six months, Corinne learned English in preparation for her next trip to Kenya. Corinne corresponded by mail with Priscilla because Lketinga was illiterate, and Priscilla told her Lketinga was out of jail.

She went with her younger brother Eric and his girlfriend, Jelly, and Lketinga was at the hotel in Mombasa to greet them. The hotel did not usually allow blacks in, particularly Masai, unless they worked there. Lketinga sometimes danced in shows at the hotel and was able to get permission to greet Corinne. Jelly’s first impression was: “He seems foreign and wild-looking.”

Priscilla offered to move in with a friend so Corinne could sleep in her hut and spend more time with Lketinga. Corinne accepted and moved out of the hotel, although the managers warned her that she would “end up with no money or clothes.”

When Corinne and Lketinga had sex, she was disappointed. He didn’t even kiss her. “I feel a pain, hear strange noises, and it’s all over. . . This was not at all what I had expected. . . It’s only now that I realize that this is someone from a completely alien culture.”

Corinne had girl talk with Priscilla and found out that Masai think kissing disgusting — “mouths are for eating.” Masai don’t touch each other’s genitals, and women cannot touch a man’s face or hair. Priscilla said, “We’re not the same as white people. Go back to Marco. Come to Kenya for the holidays, not to find a partner for life.”

Corinne was stubbornly in love, and after Eric and Jelly went home, she continued to stay in the crude hut with Lketinga. Going to the toilet meant walking far from the hut, climbing up a six-foot ladder, and squatting over a hole. She accompanied Priscilla to learn the daily routines of Masai women, such as walking to a well to fill 5-gallon containers of water. Priscilla was skilled at hoisting heavy containers up and carrying them on top of her head. Corinne struggled to keep up.

Masai women fill their water containers.

Corinne’s next disappointment was finding out that Masai men and women cook and eat separately. “All my romantic fantasies of cooking and eating together out in the bush . . . collapse. I can hardly hold back my tears, and Priscilla is looking at me in astonishment. Then she breaks out laughing, which makes me furious . . . .”

Corinne met two German expats who hooked up with Masai men. She got to know a German woman named Ursula, who had been married to a Masai for 15 years. He was a lawyer who had adopted Western customs and dress, but Ursula explained, “He still has enormous difficulty with the German way of thinking. Now look at Lketinga: He’s never been to school, can’t read or write and barely speaks English. He has absolutely no idea of European customs and manners, let alone the Swiss obsession with perfection. That’s doomed from the outset!”

Because women had no rights in Kenya, Ursula suggested instead that Corinne invite Lketinga to visit her in Switzerland. Corinne took him to get a passport, but the Kenyan passport officers laughed and said he couldn’t get one unless he put on proper civilized clothes. She bought Lketinga an outfit and helped him get dressed. When he needed to undress later, he tried to take the pants off by pulling them over his shoes; he couldn’t figure out that it would be easier to take his shoes off first. Bureaucracy in Kenya would be a never-ending challenge, and Corinne ultimately gave up on getting Lketinga a passport.

The proposal

Corinne proposed to Lketinga, with Priscilla translating. He said that since she had a good business in Switzerland, she shouldn’t sell it, but instead return to Kenya two or three times a year. She replied, “Lketinga, when I do something, I don’t do it by halves!”

Although he had not accepted her proposal, when Corinne’s tourist visa expired, Lketinga asked her to promise to return. She promised and meant it. She spent the next three months in Switzerland selling her business and belongings. “Everyone who knows me thinks I’m crazy.”

Perhaps there was something in Switzerland that Corinne wanted to escape, something left unmentioned in her memoir. On her flight back to Kenya, she thought, “I’m free, free, free!” and she felt “an ecstatic feeling of weightlessness.”

Corinne had just given up her whole life for Lketinga, but he wasn’t waiting for her at the airport. Priscilla was. When Corinne asked, she explained, “Please! I don’t know where he is!” Corinne stayed with Priscilla until they found a Masai who knew where Lketinga was.

Priscilla lived in Mombasa to make money and visited her husband and children in their rural village only twice a year. She took Corinne on one of these visits. The richest man in Priscilla’s tribe, a 35-year-old, was marrying his third wife, who was twelve. That’s how Corinne found out that the Masai could “have as many wives as they could feed.” The man asked to marry Corinne, also, and asked Priscilla how many cows she cost. Corinne wasn’t interested. Lketinga was the only African man she was ever attracted to. She caught fleas and lice on that trip.

Corinne eventually heard that Lketinga went back to the bush village he was from, so she set out for it and found him in a town called Maralal. Lketinga and Corinne went back to Mombasa together and spent a few blissful weeks making Masai crafts and selling them to tourists. Then Lketinga began to stay out late, drinking with his friends.

There was an incident when Lketinga’s behavior was very bizarre. He acted as if he didn’t know Corinne, he thrashed around, and he imagined that lions were attacking him. Priscilla brushed the incident off as “Mombasa Madness,” explaining that Masai warriors from the interior sometimes “go crazy” in the coastal city. This most likely had to do with a plant called miraa that they would chew to get high, which could occasionally cause psychotic episodes.

Corinne went to Nairobi to renew her visa, and when she got back, Lketinga was gone. He was in Barsaloi, the rural village where his Samburu people were from. Priscilla told Corinne to forget about Lketinga. She said the other warriors threatened him, and “it would be dangerous for a white to set herself up against all the others.”

Corinne wasn’t afraid; she was angry that Lketinga’s friends were interfering. She traveled to Barsaloi, where Lketinga was living with his mother (“Mama”) and a 3-year-old niece. When he saw Corinne, he laughed. “I know always, if you love me, you come to my home. Now you are my wife, you stay with me like a Samburu wife.”

Life with the Samburu in Barsoloi

Corinne moved into Lketinga’s manyatta house, which was made of branches plastered in dried cow dung. There was an indoor fire for cooking that filled the hut with smoke. Corinne coughed and her eyes teared, but Lketinga and his family laughed at this. Corinne would get covered in soot, and when she bathed in the river, water would run black off her skin.

A manyatta in the village of Ntilal. (Credit Image: © Iris Schneider/ZUMA Wire/ZUMAPRESS.com)

A fence of thornbushes surrounded the manyatta, protection from predatory animals. The family’s goat herd came inside the thornbushes at night, and their droppings attracted flies that buzzed constantly around Corinne’s head. Lketinga showed Corinne a bush three hundred yards away from the manyatta, which would be her toilet. There was no toilet paper; Samburu cleaned themselves with rocks.

Food was scarce. Somali merchants sold bags of rice infested with beetles. A mission gave maize meal to old people. The Samburus’ main food source was their goat herd; they routinely slaughtered goats for meat and drank the blood. Corinne was disgusted at first, but she was resolved to get used to it. She accompanied Lketinga once as he spent the day with the herd. Out in the bush all day during the dry season, she felt like she was dying of thirst. Lketinga found water by digging into a dry riverbed until a dirty puddle appeared. Masai women did not usually do this work, and Corinne decided once was enough. The men who were not herding goats did almost no work, while the women fetched water, gathered firewood, washed clothes, and milked goats.

Masai with goats.

Corinne went to the Catholic mission, the most luxurious building in town, and introduced herself to the two Italian priests. They were cold to her at first, but Father Giuliani eventually became a good friend who helped Corinne in many ways.

Corinne decided to buy a car so she could drive to Maralal for food and toilet paper. There were no roads. It was a four-hour drive over the smoothest route through the bush and a two-hour drive over a rockier, steeper route. The priests always chose the longer route. They gave Corinne a ride to the town, where she bought a used Land Rover. Cars were scarce, so she had to pay more than it was worth. She tried the shorter route to get home, but was delayed by a herd of buffalo that blocked her way. Later, her engine stalled as she drove down a rocky hill.

When she returned to Barsaloi, the Samburu and Somalis gathered around her car, shouting, “Mzungu! Mzungu!” — the Swahili term for a white person. Corinne was very generous when she first got the car. She used it to bring 20 women’s water containers to the river and brought them back filled. She gave rides to as many people as she could fit in the car. However, she eventually felt taken advantage of and started charging for rides.

Corinne and Lketinga developed their own way of communicating: a combination of broken English and gestures. They discussed their future. Lketinga wanted polygamy and eight children. Corinne wanted monogamy and two children. She eventually agreed that if she hadn’t conceived a child within two years, she would allow him to take another wife, but she hoped he would get used to monogamy.

Pole, pole. (Slowly, slowly)

The local police chief told Corinne that she and Lketinga had to be married in a civil ceremony because a traditional bush wedding would not be recognized if the bride was European. They drove to Maralal to get married, but after waiting in line at the office, Lketinga realized he had lost his ID card. It would take two months to replace. They found out there was a six-week mandatory waiting period between getting the license and getting married, but Corinne had only three weeks left on her visa. They were stranded in Maralal for a few days because the gas stations had no gas.

A lot of the book is about how inefficient life was in Kenya. Any errand, from food shopping to getting a visa renewal, was an ordeal that could take days, weeks, or months. When Corinne got impatient, she was told, “pole, pole” — Swahili for “slowly, slowly.” Many times, government workers deliberately made things difficult because they were hoping for a bribe. Corinne assumed people were dealing with her honestly and was surprised more than once when black officials admitted that they really just wanted a bribe. She was living on a shoestring budget and chose to do things the hard way rather than waste money on bribes, so her civil ceremony had to be postponed twice.

Government workers were often rude. In Nairobi, when Corinne told the woman renewing her visa that she intended to marry Lketinga, the woman called two of her colleagues over to laugh at the couple.

Sometimes Corinne needed public transportation, which consisted of matatu buses that had no schedule. The drivers wouldn’t leave until the bus was full. When few people were traveling, Corinne could get on a bus and sit for an hour or more before it left. When the demand for buses was high, it took Corinne two days to catch a bus. All vehicles seemed to be clunkers that stalled or broke down. Because there were few paved roads, punctures were common. Trips were constantly halted because of tire damage, or because vehicles got stuck on rocks or in mud; then the choice was to wait for help or leave on foot.

Disabled vehicles left Corinne stranded and suffering with no food or water. She was usually saved by white people. A British couple who gave her a ride in their Land Rover advised her to always carry two spare tires when she drove. One white couple even loaned her their car battery the day before they had a flight to catch. Corinne asked Lketinga to return the battery to them since he was headed their direction, but he didn’t bother, and Corinne was furious when he came home with the battery.

Gifts from Europe

Corinne visited Switzerland before her wedding and felt like she was no longer used to her own country. Her normal diet no longer agreed with her; everything seemed too luxurious. Her mother gave her a Swiss cowbell — a wedding gift for Lketinga — and a black baby doll for his niece, Saguna. Corinne packed other gifts and useful items such as blankets, clothing, food, and first aid supplies. She later became an impromptu nurse, because when word got out that she had first aid supplies, injured people appeared on her doorstep.

Lketinga loved the red blanket that Corinne gave him, and the Samburu were in awe of her cassette player. Eric and Jelly recorded messages for Lketinga and he recognized their voices. Corinne wrote, “I’ve never seen such genuine pleasure and amazement from everyday European things.”

When she offered Saguna the baby doll, the child ran away screaming and the adults recoiled in horror. They had never seen a doll before and thought it was a dead baby.

Malaria

The rainy season came with a big storm that washed away many manyattas. Flashfloods killed people and livestock every year. Corinne’s home flooded, too, and the moisture brought mosquitoes that attacked her all night. Her face was bitten so badly that she could hardly open her eyes. She decided to buy a mosquito net, but she had already caught malaria. She was in Nairobi when the first symptoms appeared; she was suddenly dizzy, extremely thirsty, and too weak to walk.

Lketinga took her to the nearest place he could find where she could lie down: a rent-by-the-hour hotel. She had vomiting, diarrhea, chills, and hot sweats. She had heard horror stories about the hospital in Nairobi, so she refused to let Lketinga take her there. She sent him out to buy anti-malaria pills, which gave her the strength to drive back to Maralal, but she fainted on arrival and had to be taken to the hospital by ambulance.

Corinne had a fever of 105.8, but the Maralal hospital had no medicine for malaria. She took pills to treat the symptoms, and had an allergic reaction that caused hives. Lketinga brought her a goat leg, but she couldn’t keep any food down. The black hospital staff were unsympathetic: “The nurses curse me because every time I eat something, I throw up.”

Corinne’s German expat friend, Jutta, visited her on her fifth day in the hospital. She was horrified by Corinne’s appearance, and urged her to go to the missionary hospital in Wamba, which had white staff. “Five days and they haven’t given you anything? You’re worth less than a goat . . . Maybe they don’t want to help you.”

Corinne did not think she could manage the four-hour drive to Wamba. She left the useless hospital and rested in a boarding house that she usually stayed at when she went to Maralal.

When she got some appetite back, Corinne and Lketinga went to a Samburu festival. It was important for Lketinga to attend and take part, and he was already a few days late. A new village of 15 manyattas was built for the festival. The pathways between them were covered in cow pies that attracted swarms of flies. Corinne sat in front of Mama’s manyatta while Lketinga went off with the other warriors. No one spoke to her for hours and she felt “left out and forgotten.”

She enjoyed watching Lketinga take part in the traditional jumping dance, until a line of topless teenage girls started choosing men from the line of warriors. At age 27, Corinne felt old, and she worried that Lketinga would want one of these young girls as a second wife.

Young Masai people at a traditional jump dance. (Credit Image: © Imago via ZUMA Press)

Father Giuliani arrived on his motorbike, having heard that Corinne was at the festival, sick with malaria. He brought her bananas and bread, which she really appreciated, because she hadn’t been able to eat the meat Lketinga offered her. The priest feared for her life and convinced her to go back to Switzerland until she fully recovered.

When she landed in Zurich, Corinne was sickly thin and badly bruised from a four-hour ride to the airport in the back of a truck full of cabbages. “My mother can hardly conceal her horror at my appearance.”

She stayed for two weeks and attended Eric and Jelly’s wedding. Everyone asked her what life in Africa was like. “Every one of them tries to bring me to my senses. But for me common sense is in Kenya, where my great love and a life with meaning are.”

Civil ceremony and honeymoon

Corinne finally married Lketinga in a civil ceremony, but she had to give him a kick to remind him to say “Yes” during the vows. Just when she thought her long battle with red tape was over, she was told she needed to go to Nairobi to apply for permanent residency.

Lketinga’s older brother was a witness at the wedding. He had never been to a city before, so they brought him to Nairobi. He gaped at everything, particularly the multi-story buildings. When the clerks told Corinne it would take a week to process her application, she decided to spend the time in Mombasa as a makeshift honeymoon. She thought it would be nice if Lketinga’s brother could see the ocean.

The older brother was so afraid of the ocean that he insisted on leaving the beach after 10 minutes. Corinne did not want to go to the beach alone, so she spent her honeymoon in bars, paying the tabs for her new husband and brother-in-law. When she complained to Lketinga about the expense, he didn’t care and kept ordering drinks.

Samburu wedding

There was also a Samburu wedding in Barsaloi. Since they would not be allowed to live with Mama after the marriage, Lketinga hired four women to build them a manyatta, paying them one goat. Corinne used her Land Rover to fetch branches, which the women used to frame out the house. The walls were plastered in cow dung, but since the Samburu in Barsaloi only had goats, Corinne had to drive to another village to fill her car with cow pies, and it took three trips to get enough. The women smeared the dung on the house with their bare hands and laughed at how Corinne couldn’t tolerate the smell. It took a week to dry and harden, and for the odor to fade.

The exterior of a typical manyatta in the village of Ntilal. (Credit Image: © Iris Schneider/ZUMA Wire/ZUMAPRESS.com)

Corinne’s manyatta was sixteen by eleven feet, with a fireplace near the entrance, and two bedrooms. Corinne and Lketinga’s bed was a straw mat on top of a cowhide, and a blanket Corinne brought from Switzerland. There was a guest room because Samburu custom required them to feed and house any warriors who were passing through.

Corinne wanted to get married on Christmas, but dates on the Gregorian calendar meant nothing to the Masai. They planned their special occasions according to the moon’s position, but they weren’t able to determine it in advance. No invitations were sent out; people learned of the wedding by word-of-mouth, and Corinne had no idea how many people would come. “The more people, particularly old people, who turn up, the more respect we’ll get.”

Lketinga’s younger brother, James, explained the Samburu wedding ceremony to Corinne, and she was shocked to hear that it started with the bride getting a clitorectomy. “I feel as if I’ve been shot down from the sky.” Corrine told Lketinga she would rather call off the wedding than get the clitorectomy. He already knew that she wouldn’t do it, and had been covering for her by telling everyone that white women have the procedure done when they are babies.

Corinne brought a white wedding dress that she saved from her bridal shop and changed into it at the mission. When Lketinga arrived — “painted magnificently” — he asked with irritation why she wanted to wear a dress like that. She answered, “To look pretty.”

The Masai had never seen a white wedding dress and they were fascinated. The children gathered around Corinne, jumping with excitement, and she gave them candy, while James handed out tobacco to the elders. Whether out of respect or curiosity, 250 adult guests turned up for the wedding, bringing plenty of children and dozens of animals. It was the biggest wedding ceremony Barsaloi had ever seen. They quickly ran out of food, but Father Giuliani produced a forty-pound sack of rice as a wedding gift.

There were no vows and no ring exchange. The day was spent cooking, eating, and dancing. Men and women danced separately. This made Corinne feel neglected. Her husband spent more time with his buddies than with her, and she missed not having her own family there.

At sunset, the guests announced their wedding gifts. Samburu men and women owned their animals separately, so the guests announced who the gift was for and what it was. Corinne received 14 goats, two sheep, a rooster and hen, two calves, and a small camel. Lketinga received the same. When the party was over, Corinne retired to her new manyatta, but her husband was still celebrating with his friends.

Continued in Part II.