The Ordeal of Sincere White Liberalism, Part I

Anastasia Katz, American Renaissance, January 26, 2024

Subscribe to future audio versions of AmRen articles here.

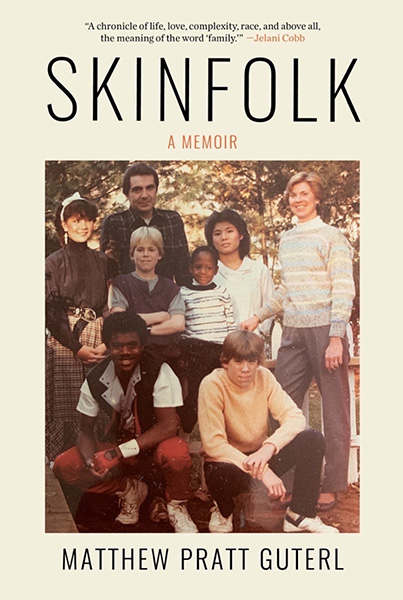

Matthew Pratt Guterl, Skinfolk: A Memoir, Liveright, 2023, 320 pages

In his memoir, Skinfolk, Matthew Pratt Guterl describes growing up as a white boy with four non-white adopted siblings. Mr. Guterl was raised in a small town in New Jersey in the 1970s and 1980s, with one white biological brother and four adoptees. His parents were well-educated, environmentally conscious liberals who wanted to have a “family of the future” that would be living proof that integration works. The author grew up believing he was part of a family with a unique purpose, and the word “us” had a special meaning.

In his memoir, Mr. Guterl refers to his parents by their first names, Bob and Sheryl, and to his siblings by childhood nicknames. Bob was a tall, dark-haired man who began as a lawyer and later became a state judge. Sheryl was a blonde, blued-eyed teacher. Matthew Guterl was born in 1970, so he was 53 when this book was published. He has his mother’s fair coloring.

The family lived in a house with a white picket fence, across from a general store, where shoppers often cast curious eyes on the multiracial children playing in the yard. Bob wanted the family to have a traditional, all-American house, so he spent a lot of time maintaining the picket fence, even though a more modern fence would have been less work.

The author — whom I will henceforth call Matt to distinguish him from his father — gets off to a slow start but once the adoptions begin, the memoir becomes a fascinating account of the racially self-destructive mindset of liberal whites.

Matt grew up listening to his father tell the story of Noah’s Ark and likening their family to it. Instead of two animals of each kind, they have two children of each race. “Early on, I am taught to see the house with the white picket fence as a biblical ark for the age of the nuclear bomb, of race riots, of war.”

Years later, when Matt was grown, Bob said he had wanted “two of every race” but had forgotten to “collect two Native Americans to complete the matched sets he had assembled.”

The inspiration

When Matt Guterl was a baby in 1971, The Population Bomb by Paul Ehrlich had a huge influence on his parents. It pushed for Zero Population Growth, which was trendy in the early 1970s. Matt writes that he now thinks it was “a wily bit of pop-science scare-mongering,” but Sheryl believed Zero Population Growth “made sense” and likened it to recycling. She wrote on her first adoption application that she was chair of her township’s recycling committee. Bob grew up in a large, Irish Catholic family and wanted a big family. Adoption was therefore a way not to be “wasteful.” Matt says his parents wanted “to make a political statement.”

Bob and Sheryl were also influenced by “Why We Adopted an Interracial Child” in the May 1971 issue of Family Circle. It was written by Jim Bouton, a retired New York Yankees pitcher, who adopted a Korean boy. Bouton wrote: “The Zero Population Growth people have the right idea. I don’t think we have the right to litter up the world with our offspring.”

Bouton argued for a tax reduction for families who adopt two or more children and for free vasectomies. Bob said similar things to his son Matt. The Boutons had “seriously thought” about adopting a black child, but “just didn’t have the courage” because they worried that a black child would be torn between “the Negro community” and the WASP world. They were afraid a black child would reject them when he grew up.

Adoptions from Asia

Bob and Sheryl Guterl had the courage the Boutons lacked, but their first adopted son was from Korea. They contacted Welcome House, the agency the Boutons had used. Welcome House was founded in 1949 by Pearl S. Buck, the novelist famous for The Good Earth, as an alternative to traditional adoption agencies that placed children with parents of the same race. Welcome House was looking for homes for Korean and American Indian children and asked if the Guterls had a “coloring preference.” Sheryl wrote “none.”

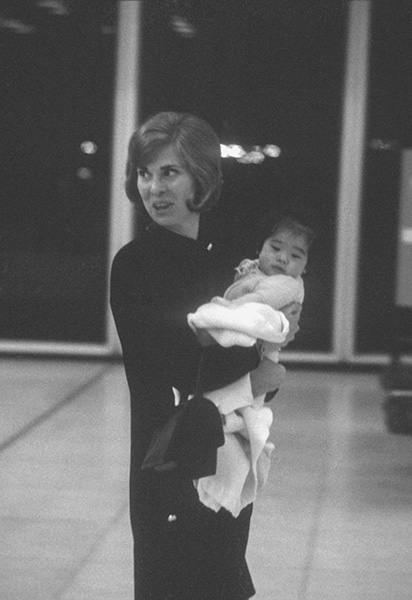

Bob and Sheryl adopted an infant Korean child in 1972. Matt was born in 1970 so he has no memory of life before that. He refers to this brother as “Bug” — “a nickname so old that it has no genesis that we can recall.” When Bob and Sheryl went to JFK airport to collect their new son, all of the other couples waiting for the plane of Korean orphans were white.

Sheryl at the airport holding Bug.

After adopting Bug, Bob and Sheryl became “model adoptive parents” at Welcome House where they led parent workshops on international adoption. They inspired another relative to adopt, so Matt had a cousin who was also from Korea.

One year later, in 1973, Sheryl gave birth to a boy named Mark. That would be a white full brother, but Matt writes practically nothing about him for the rest of the book. Did he dislike Mark? Did he want to concentrate only on interracial adoption? The reader can’t tell.

When Matt was five years old, his parents told the children they would be getting another brother. It was a dark conversation about refugees, war, and a flight across the Pacific. “Bear” was a biracial black and Vietnamese boy whose father was a soldier stationed in Vietnam. Bear’s biological mother, Tran Thi Thung, had three children, all fathered by different black soldiers. Matt avoided writing plainly that Miss Thung was a prostitute: “She did what she had to do to make money, serving as a serial secret wife for GIs.”

Miss Thung said in an interview with the New York Times in 1974 that she placed her three children in an orphanage because of poverty and the animosity toward biracial children. “No Vietnamese man will take three black kids,” she said. As an adult, Bear said he still remembered the “death stares” he got in Vietnam. He was sure the Vietnamese wanted to kill him.

When each adopted child was first brought home, the family threw a “Welcome Home” party. At Bear’s party, Matt gave his new brother his bicycle as a “welcoming gift,” but only to please his parents. He wrote that he had a “deep reservoir of anxiety and stress, a desire to overperform welcome and generosity.” He tried to “snuff out” doubts about the adoption and felt the white guilt his father instilled in him.

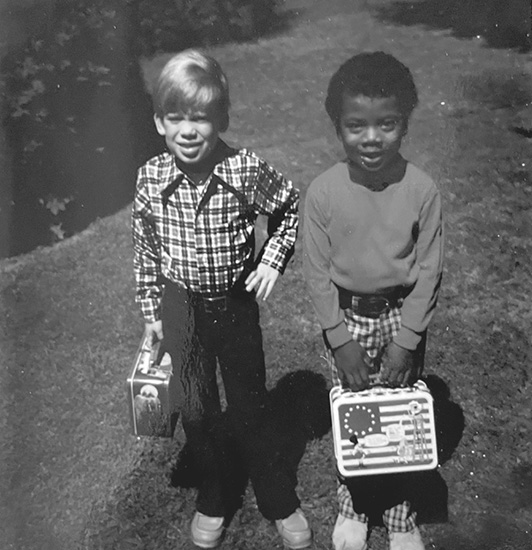

Matt and Bear were only days apart in age and eventually became very close, but five-year-old Bear’s arrival was hard for Matt. He went back to baby talk, and sometimes did not talk at all. Many children revert to baby talk when a new sibling is brought home; it is a cry for attention. Sheryl had a moment of regret when Matt’s speech regressed, wondering, “What have we done?”

When Matt and Bear were seven, Bob and Sheryl visited the family who adopted Peter, Bear’s older half-black, half-Vietnamese half-brother. Bear immediately clung to his biological brother, leaving Matt feeling cast aside.

Matt always compared himself unfavorably to his adopted “twin:” “In every single way, he is physically superior to me. The coaches elevate Bear to the traveling baseball teams, which compete statewide. I stop playing sports soon after. . . . I watch from the sidelines as he wins trophies.”

They got after-school jobs delivering papers. “It takes me longer to deliver the papers. Bear hurls himself around town, sailing in the air after hitting a small bump, cutting over lawns and corners. I ride in straight lines, avoiding the mud, the puddles, the slippery gravel. It takes me much longer because I am so much more vigilant and so much more reserved.” Bear was also a good student.

Bob and Sheryl adopted Anna in 1977, when Matt was seven and she was thirteen. “Anna materializes in our midst with an explosion of brightly colored silk, bringing several beautiful traditional Korean dresses.” Matt described her — half-white, half Korean — as “Heartbroken, having lost everything she has ever known.” Anna arrived knowing some English, and she begged her adoptive parents to find Korean things in New Jersey. Bob and Sheryl took her to Korean-language Catholic masses and to Korean grocery stores. The family learned to eat with chopsticks. Sheryl recalled: “She missed her culture. We did what we could. It would be so much easier now.” In 1977, there were approximately 30,000 Koreans living in the United States. By 2021, the number was two million.

Anna was older and left home more often than her four adopted brothers. She went on dates and got a job. Her Japanese bosses made anti-Korean comments. When she shopped at the Korean grocery, the Korean ladies referred to Anna with slurs because she was biracial.

The n-word

The family went on a camping trip in Virginia, and Bob and Sheryl were disturbed to find that black campers were segregated from whites. When the Guterl boys played with white children, the whites referred to Bear as “boy,” even after being told his name. Bob and Sheryl decided to go north for vacations after that, but in New Hampshire, Matt had a much more unpleasant encounter. Bear was noticed as soon as they arrived. Alert to “the racial electricity,” Bear stayed close to his parents, but Matt went bike riding alone.

A group of white boys who had seen the family chased him, shouting, “N—! Get the n—!” They surrounded him, and one boy said, “You’re the n—’s brother.” Another said, “Get him out of town.” Matt, badly frightened, broke through the circle and rode away. He realized that the boys saw his brother only as black, not half-Asian. He thought the boys let him go because he was white, and would have beaten up Bear.

The parents of the boys who chased Matt apologized to him. Matt didn’t think he deserved the apology, even though he was the one who was chased. He thought they should apologize to Bear. “White people apologize to me . . . because I am white like them, and because I represent an integrated future in which white people still play a meaningful role.”

Bob and Sheryl stopped vacationing in Virginia because of racism, but they lived in a majority-white town in New Jersey, and did not take their children to black areas. Young Matt met large numbers of non-whites only at Welcome House picnics.

As the first-born, Matt should have had a special role in the family, but Bear instantly became the older brother, and Anna was years older. Matt’s role became that of representing whites. He wrote that being “the white child” was his “function in the family,” but because he was always with Bear, white children saw him as black.

Matt and Bear

Matt had thick lips and classmates called him “N— Lips.” In the seventh grade, the bullying was so bad that his parents took him to a plastic surgeon to reduce his lips. While healing from the painful surgery over the summer, Matt fantasized about how his classmates would see him as his “defining role,” the white kid, when he went back to school. They kept calling him “N— Lips” anyway, and Matt was “instantly deflated, so inconsolable. . . . Blackness has attached itself to me.”

This was a big burden for a 12-year-old — rejected both for his appearance and because his adopted brother was black. He was also disappointed in himself for not fulfilling his role as a representative of whiteness. He believed his family was on a mission to change the world by example, but it didn’t seem to be working. “That nickname . . . is another reminder . . . of the naivete of our family’s progressive narrative. Not everyone, I realize, has heard Bob’s kitchen-table sermons about the global catastrophe around the corner, about the glorious future predicated on our rainbow tribe.”

A family built for virtue signaling

Young Matt didn’t like the constant gaze of onlookers as his parents showed off their diverse family: “A hundred pairs of eyes on us every day.” His parents’ decision to create a multi-racial family meant the children were like celebrities, always aware they were being watched and judged.

Matt had fond memories of playing with his brothers and sister in their backyard, because the neighbors couldn’t see them. The family continued to vacation in New Hampshire, and returned every year to a secluded lakeside cabin: “What I remember most about this place is the absence of any sight lines, of any watchers, of any gaze.”

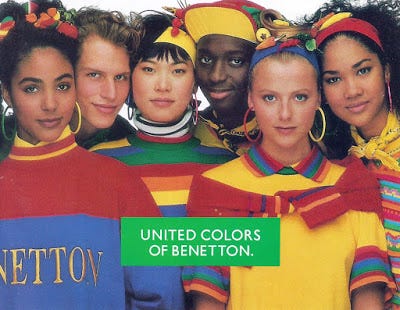

The family would arrive in church “like a walking and breathing rainbow, a Benetton advertisement brought to life.” They switched churches a few times but the children were always doted on. Matt, Bug, and Bear always played the three wise men in Christmas pageants. “Having us carry the gifts up the center aisle, in our cheap Woolworth’s beards and our flowing robes, sends a powerful message to a new parish, formed at the far edge of white flight . . . that if the future is going to be confusingly diverse, it will at least still be Christian.”

Ancestry and white guilt

Sheryl was a descendant of William Pratt, a founder of Hartford, Connecticut. She took the family on a trip to Old Saybrook, Connecticut, which has a monument to William Pratt. Sheryl was proud to find streets named after him. A guide gave them a tour, telling the heroic history of Old Saybrook’s early settlement, but Sheryl’s white guilt set in when the guide told them that William Pratt led troops in the Pequot War. He fought in The Battle of Mistick Fort, in which 90 English and 100 allies (Narragansett, Mohegan, Niantic and Connecticut River Indians) killed more than 400 Pequot in an attack on a fortified Pequot village. Pratt received one hundred acres of land; his descendant Sheryl was horrified.

Matt says she sat “with the enormity of this tale . . . Those streets, those statues . . . are all honoring her ancestor for the merciless Battle of Mistick Fort, for the burning alive of men, women, and children.” It did not matter that Pequot warriors started the war by slaughtering unarmed whites, or that the 100 Indians allies were happy to kill Pequots.

Matt’s father, Bob, had an “interest in finding some obscure, random ancestor, some genetic flourish that will enrich what he sees as an otherwise all-white background.” On the application for his first adopted child, Bob claimed he had some American Indian ancestry. Apparently, there was a family rumor of a French-Canadian grandmother who was part Indian. Matt wondered if this “reckless reference to an Indigenous heritage” made it easier for him to adopt non-white children. He was disgusted that his father falsely claimed to be part Indian, not that his father didn’t think his own background was “rich” enough.

Matt took a DNA test. There was zero Indian ancestry.

Adoption leads to immigration

When Bear was in the eighth grade, his biological mother sent a letter to Sheryl, pleading to let her communicate with her son and asking for money. Miss Thung also asked Sheryl to convince Bear’s other half-siblings, Peter and Amy, to write to her. When Bear finished college, he and his half-brother brought Miss Thung to the United States and Bear helped her get American citizenship.

The adoption from the Bronx

When Bob and Sheryl decided to adopt a sixth child during the summer of 1984, they convinced 14-year-old Matt he was part of the decision. His parents held a family meeting, at which Matt recalled, “We discuss[ed] our aims and ambitions,” as though bringing another child into the family was his own ambition. Matt thought there was an unlimited capacity for more. He was a true believer in his parents’ mission; every human problem could be solved by immigrants assimilating into the “white heterotopia of the American small town, the American suburb, and the American family.”

His parents discussed adopting a non-white disabled child, and the five children they already had responded by saying they didn’t want a sibling with visible and disfiguring scars, a reaction Sheryl thought was “terrible.” Matt, however, liked the idea of being big brother to a crippled little sister: “I imagine a sister named Amy from India, a young girl with leg braces, someone smaller and younger, who I will carry up and down the steps.”

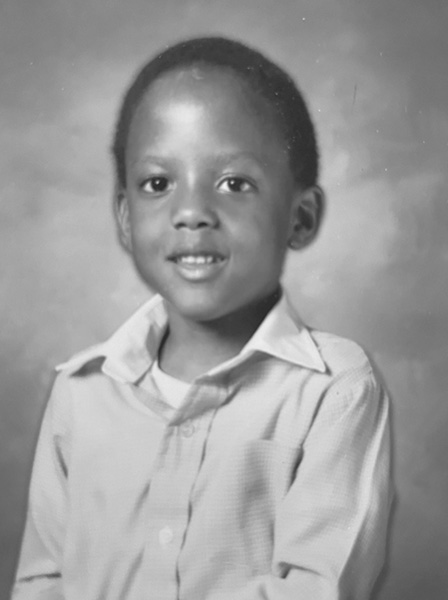

Bob decided that he wanted another black child, to turn Bear into a matched set. He and Sheryl showed their children a photo of a little black boy named Eddie, whom Matt thought looked like Webster, the main character in a sitcom about a white couple that adopts a black child. Matt got used to the idea and he even bragged to a girl he liked that his family would be adopting a boy from the Bronx, which sounded exotic.

Eddie

Matt recalled that in the 1980s there were stories on the news about “crack babies.” He remembered diagrams of crack-damaged brains shown on TV. The adoption agencies told prospective parents like Bob and Sheryl that crack babies were “disabled.” Eddie, the boy they chose to adopt, was a crack baby. Matt thinks it was unfair to stigmatize children of crack-addicted black mothers; he believes society saw blackness itself as a disability.

The adoption agency played on Bob and Sheryl’s desire to be saviors, telling them that if Eddie stayed in the projects, he would not live to be 30, although they did not explain why. “When we are told that he will die without us, we believe it.”

There was a presumption that living in “all-white, small-town America” would save Eddie “from a horrible fate in the dystopian city. . . . We believe, mistakenly, that we are magic.”

Interviewing his mother for his memoir, Matt asked Sheryl if she had any “warm, treasured memories with Eddie.” She replied, “It was difficult from the start.”

The day Eddie came home, the family had its typical Welcome Home party, but just as it started, Eddie grabbed “our Aunt Joan’s” purse and made “a dash for the end of the driveway.” Bear caught him and told him he didn’t have to steal anymore. Eddie was six years old.

Continued in Part II.