The Tragedy of Hannah Payne, Part II

Anastasia Katz, American Renaissance, December 29, 2023

Subscribe to future audio versions of AmRen articles here.

Continued from Part I.

Prosecution witnesses

The prosecution’s first witness was Vickie Lynn Herring, Kenneth Herring’s sister. She said her brother was a diabetic and he needed to inject himself with insulin.

Nigel Hunter next questioned Terry Robinson, the black prison guard. He said he worked in the prison infirmary, taking care of sick inmates, and making sure nurses and inmates are safe. He had worked with diabetics, and watched nurses help when they went into shock. He said diabetic patients have glassy eyes or yellow eyes when they suffer from diabetic shock.

On May 7, Mr. Robinson was off duty and not in uniform. He saw Mr. Herring’s vehicle hit the side of a large truck and saw the driver slump over inside. The semi-truck driver came out and Mr. Robinson asked if he was OK. He said he was. They checked on the man who caused the accident.

Mr. Herring seemed dazed. He asked, “What happened? What happened?” Mr. Robinson told him he had been in an accident. He noticed Mr. Herring’s eyes were glassy, so he concluded he was in diabetic shock. He did not smell any alcohol, but he thought “the gentleman was out of it.” Mr. Robinson called 911, saying he thought the driver who caused the accident fell asleep at the wheel.

Mr. Herring’s red truck was leaking fluid, and was badly damaged in front, and Mr. Robinson didn’t think it would run. Herring got out of his truck and inspected it. Mr. Robinson asked him — a few times — if he needed an ambulance. Mr. Herring said, “I’m ready to go,” but Mr. Robinson told him he couldn’t go anywhere because he was just in an accident.

Mr. Herring turned the truck’s engine on, and Mr. Robinson told him not to go anywhere. He said, “Sir, you can’t do anything. You can’t move. You can’t move.” Then Mr. Herring “put it in drive and floored it.” Mr. Robinson says he was shocked. He said he regrets that he didn’t take the keys away, but he didn’t think the damaged truck would run. Mr. Robinson said Miss Payne had no conversation with Mr. Herring before Mr. Herring drove away.

At least 20 minutes had passed since he called 911, and no emergency help arrived, so he called again. That call was played in court; the audio was unclear:

Mr. Robinson: The driver who caused the accident . . . I think he’s (unintelligible) on (unintelligible). There’s something going on with him. . . . He’s driving off. (more excited tone) He’s driving up Riverdale Road! Get his tag! Go, go, go get the tag! . . . gray hair, blue shirt . . . The lady in the Jeep, who witnessed the accident, she turned around and she’s gonna get a (unintelligible) on the vehicle.

Mr. Robinson acknowledged that as Miss Payne was driving her Jeep, he told her to go get Mr. Herring’s tag, but he said, “I did not tell her to apprehend or accost or stop the vehicle to get a picture of the tag.” He said he also did not tell her to use deadly force to stop the car.

Police arrived about 10 minutes after Miss Payne left. Mr. Robinson wrote a statement for police and he did not mention diabetes. He wrote that the driver of the pickup “looked impaired.” When detectives interviewed Mr. Robinson, he told them that they were waiting a long time for police to arrive and Mr. Herring “was getting irritable.” He wanted to leave, but Mr. Robinson told him, “Your car is still smoking, you don’t want to do that.” Mr. Herring got back in the driver’s seat, saying, “What laws have I broke?”

Mr. Robinson told the detectives that he thought about trying to take Mr. Herring’s car keys, but he “didn’t feel like going through all of this.” When Mr. Herring sped away, the semi driver was only a few feet from him. He told the detectives he had he told Miss Payne, “Don’t pursuit,” as she drove after Mr. Herring. He did not say “Don’t pursuit” on the 911 recording.

On cross examination, Mr. Robinson said, “I was trying to apprehend this person,” — meaning Mr. Herring. Mr. Tucker asked, “You were trying to apprehend?” Mr. Robinson changed his mind: “No, I wasn’t trying to do anything.”

Ashley Jackson, a black woman, was driving home from work when she noticed Miss Payne’s Jeep weaving in and out of traffic. Miss Jackson said, “She almost ran me off the road. She was speeding.” Miss Jackson said her co-worker, whose car was behind hers, called her and said, “She almost ran you off the road. She’s going to cause an accident.”

Ashley Jackson

Traffic was stopped ahead. She said Miss Payne had maneuvered her car in front of another car and stopped it. She saw Miss Payne at the driver’s side door of a truck, fighting the driver through the window, and yelling, “Get out of the car, motherfucker!” Miss Jackson said her demeanor was “very aggressive,” and “It was a big scene.”

She saw the defendant pull a gun and heard shots immediately after that. She said the victim leaned back in his seat and his eyes went white. Miss Payne said, “Now you need an ambulance.” Miss Jackson and other witnesses ran towards Miss Payne. Miss Jackson said, “Oh my God, you just shot him!”

A cop arrived and asked what happened. Miss Jackson said the defendant tried to tell the police that the man in the car grabbed her gun, “but everyone immediately said, ‘No, that’s not true, that’s not true! The man never grabbed her gun!’” Police put Miss Payne in handcuffs. “She had no remorse at all,” Miss Jackson said.

The defense attorney noted that Miss Jackson had said, “Traffic was barely moving,” but also said that Miss Payne was weaving and speeding. Miss Jackson said the defendant’s car weaved as it was “coming up towards my place,” then almost ran her off the road and her co-worker called her.

Miss Jackson insisted that Miss Payne crashed into Mr. Herring’s truck. Yet she said, “I didn’t see how she maneuvered and landed in front of him.” She said she was certain the accident was the woman’s fault because “she was the only one who was on the scene.”

The statement Miss Jackson wrote for the police that day said, “She jumped in front of the victim’s vehicle causing the accident. She jumped out, screaming and punching the victim. She pulled a gun and shot him. She was not even remorseful.”

Teauna McCranny, a young black woman, gave inconsistent testimony. I got the impression that she had only seen bits and pieces of the incident as she passed by in a moving vehicle, and she was filling in the blanks either from imagination or from what she had heard from others. She testified that she did not see Miss Payne shoot Herring, and she did not see Herring after he was hit. She did seem genuinely upset by what she remembered, but her memories of the incident were contradictory.

Teauna McCranny

First, she said Miss Payne crossed over a median, cut Mr. Herring’s truck off, immediately jumped out of her Jeep and went to Mr. Herring’s driver’s side window, saying, “Get the F out of the car!” She said Miss Payne was “holding him at gunpoint and cussing at him” before Mr. Herring’s truck hit the Jeep. Miss McCranny also said Miss Payne did not get out of her Jeep until after Mr. Herring hit it. She could not remember anything Mr. Herring said to Miss Payne.

She said she saw Miss Payne hitting Mr. Herring. She thought Miss Payne’s demeanor was “aggressive” and Mr. Herring looked confused, but she also said she couldn’t see what Mr. Herring was doing. When asked if she saw Mr. Herring “attack the defendant in any way,” Miss McCranny said, “I did see a struggle after she jumped in his car, jumped through his window.”

During cross examination, Mr. Tucker asked if Miss Payne had actually jumped through that small car window and Miss McCranny maintained that she had. Then she changed her story and said she had not.

Miss McCranny called 911 twice, and the recordings were played in court. In the first, she said there was a merging lane and as the woman drove around the man, he almost hit her. The woman “got mad” and got out of her car, and pulled a gun and started screaming at him. He “was like, what the heck? and she said, ‘I’m just a student.’ ”

When audio from the second 911 call started playing, Miss McCranny began to cry and wiped her eyes. In the recording, she reports hearing a gunshot and she says, “She shot him.” Then she seems to be checking with someone else and asks, “She shot him?” The dispatcher told Miss McCranny the police were coming and Miss McCranny said they were already there.

Hannah Payne was accused of false imprisonment because she parked her car in front of Mr. Herring’s truck, but Miss McCranny told the prosecutor that he could have backed up and gone around her car. When the defense attorney asked her about that, she changed her mind and said Mr. Herring could not have backed up.

Miss McCranny’s written statement the day of the incident said that Miss Payne cut Mr. Herring off, so he had to brake suddenly, and he almost hit her by an inch. Miss Payne hopped out quickly, “pulled up her shirt with her gun,” then she started hitting him. Mr. Tucker asked which hand Miss Payne used to hit Mr. Herring, and Miss McCranny could not remember. Nor could she remember in which hand Miss Payne held her gun.

Shakonda Rosser, a black woman, testified that she drove by on the opposite side of the road, in the other direction. Ahead of her, she saw a Jeep abruptly change lanes and stop in front of a red truck. The truck tried to go forward and there was impact. Oil was leaking from the truck. She saw a lady get out of the Jeep go to the truck and start swinging and hitting the man in the truck, punching him hard in the chest over and over, while he just sat there. Miss Rosser stopped her car, “Because the whole thing was shocking.” Other drivers also stopped.

Shakonda Rosser

Miss Rosser heard yelling, but not what was actually said. She thought it was odd that someone would allow himself to be punched like that, rather than roll up the window. She did not see his hands at all, and he looked “confused and shocked.” Miss Rosser “thought something was wrong with him.”

Other drivers also stopped their cars. Next, the lady stepped back and Miss Rosser could see Miss Payne pull a gun and tell the man to get out of the car. Then she went back to the truck and began punching the man again. Miss Rosser said Miss Payne was looking Mr. Herring in the eye when she shot him. Miss Rosser became very emotional, breathing heavily and crying. She did not see where the gun was when the shot was fired; she only heard it.

During Mr. Tucker’s cross, Miss Rosser said the Jeep did not jump over the median and Miss Payne did not jump into the window. She said Miss Payne had not left her Jeep with a gun already in her hand; she never held Mr. Herring at gunpoint. Asked by Mr. Tucker, she said she was able to see that it was a black man in the truck and a white woman who came out of the Jeep. Miss Rosser acknowledged that the Jeep and truck were in the far-right lane, and the middle and left lane were clear, so Mr. Herring could have driven away.

Miss Rosser’s testimony that Mr. Herring did not fight back didn’t match up with Miss Payne’s injuries or torn black shirt. Mr. Tucker asked Miss Rosser what Miss Payne had been wearing, and Miss Rosser said she was wearing a white long-sleeved shirt, but that she later put a pink sweater on. Miss Payne had put on an orange sweatshirt because her black shirt was torn down the front.

Mysteriously, Miss Rosser said that a white man who had been driving on the same side of the road as Herring and Miss Payne came out of his car and approached Miss Payne as if he wanted to calm her down. Miss Payne turned toward him, and when he saw her gun, he put both his hands up, then went back to his car and drove away. Did the detectives fail to track down this important witness, or did Miss Rosser invent him? Miss Rosser seemed more credible than Miss McCranny. Miss McCranny stated that she had spoken to media about the story, and seemed to enjoy getting attention, while Miss Rosser said she declined interviews.

The deputy chief medical examiner is a black woman named Dr. Stacey Desamours. She testified that Mr. Herring had died from a gunshot wound to the abdomen, and she also found a small bruise on his upper chest by the collar bone. She was told he had a history of hypertension and diabetes. His blood sugar was not elevated at the time of death, but Dr. Desamours said the test would not show if blood sugar was low at the time of death. (“Diabetic shock” or hypoglycemia is low blood sugar.)

The toxicology report showed that there were no drugs or alcohol in Mr. Herring’s system. She could tell Mr. Herring was shot from close range; the gun had been from a few inches to three feet from his body.

Under cross, Dr. Desamours said she could not give any opinion on the angle of the gun or the position of Mr. Herring’s body when he died. No investigation had been done by trajectory experts. Dr. Desamours did say that the way someone is normally seated in a car, the bullet could not have come through the window because there was a downward angle to the gunshot wound.

A black man named Cameron Williams witnessed the incident and took the only video of the moment the gun was fired. He was reluctant to serve as a witness because his father is a police officer, so he thought he could be “a little biased.”

Cameron Williams

Mr. Williams said he got to an intersection and the light was green, but traffic was not moving, so he drove around other cars to get through. He saw Miss Payne yelling and hitting on the door or window of the red truck. He saw arguing, and he saw Miss Payne and Mr. Herring pushing back and forth, fighting over the gun, so he took out his phone to record. “Honestly, I hate to say it like this, but it was like another day in Clayton County. As I was recording, I heard a gunshot.”

He parked his car and got out. Miss Payne asked him to stay and be a witness. Mr. Williams was running late, and wanted to leave. He told police on the scene that he had a video and he emailed it to them. When detectives contacted him later, he told them he saw the two fighting over the gun, and that Miss Payne had bent down to pick up a shell casing afterwards (actually her phone).

His video was played for the jurors. It is only a few seconds long. When it starts, we see Miss Payne from behind, and her arms are both inside the truck, and her legs are pressed against the driver’s side door. She pulls her gun out with her right hand. One gunshot can be heard. Then Miss Payne bends down and picks up her phone.

The video does not look for Miss Payne, but Mr. Williams did testify that before she shot Herring, the two were struggling for the gun.

A screenshot from the clip that shows Miss Payne with the gun in her hand, was also shown to the jury. I enlarged it to see whether Miss Payne’s finger was on the trigger or the trigger guard, but the picture is too blurry to be sure.

During cross examination, Mr. Tucker had Mr. Williams look over screenshots from his video. Mr. Williams agreed that Miss Payne was standing on tiptoe as she was against the truck at one point. Mr. Williams could not tell if Miss Payne’s shirt was being pulled, and he said he never noticed anything about her shirt. He only wanted to check on Mr. Herring after the gunshot. He said he could hear Miss Payne screaming “Stop!” when they were fighting.

Detective Tracy Moore, a white woman, investigated Mr. Herring’s truck after the incident. The driver’s seat had blood stains and there was heavy damage to the front of the vehicle. The interior of Mr. Herring’s truck was cluttered. Police found a knife, a drill, scissors, clothes, cables, and a blue cooler. The knife was on the back seat.

Ryan Richie, a white police officer, came to court in uniform. He said he was flagged down by a person who said that there had been a car accident and someone had been shot. He saw a large crowd of people, and many pointed to a red pickup truck, saying that the man inside had been shot. He asked who shot him. Miss Payne said, “I did,” and she handed Officer Richie her firearm, her license, and her concealed carry permit. When he unloaded Miss Payne’s gun, he found a spent shell casing inside.

He was unable to open the driver’s side door, so he went around to the passenger side to help Mr. Herring, who was unresponsive. He called for paramedics and applied pressure to the wound until they arrived. He handed out forms to witnesses so they could write statements. Officer Richie’s bodycam video was played in court and it showed Miss Payne handing over her gun while she was still on the phone with 911.

The investigation

The prosecution showed a video of Hannah Payne being questioned by detectives at the police station. Miss Payne made a big mistake: she agreed to speak to the police without a lawyer present, and even signed a waiver.

Her story in the police station was mostly the same as her story on the witness stand. She told the detectives that Mr. Herring said, “Who are you?” and “I’ve got something for you,” and she cried when she started talking about how Mr. Herring grabbed her shirt and her neck. She said when she told him she had a gun, he responded, “Shoot me.”

She described in detail how he tried to turn the gun away by twisting her hand backwards. She mentioned that he tried to open the truck’s door at some point. She said she was trying to pull her hand out without leaving the gun behind. Her gun had a double safety, and she thought it just went off, “It was a matter of force.”

DNA swabs were taken from the gun’s slide and most of the DNA was Hannah Payne’s. There was also DNA from a man, but the forensic biologist could not determine if it was Herring’s. The crime lab also tried to take fingerprints from the gun, but only the magazine and cartridge had usable prints and results were inconclusive.

Both 911 calls were played in court. The first call was very ordinary; Miss Payne reported that she saw an accident. I listened to the second call about 50 times, and made a transcript:

911 call

Payne: I actually called 20 minutes ago for an accident and nobody showed up yet, but the guy who caused the accident and ran a red light is drunk and he got back in his car and he is about to drive away.

911: OK, did you get a tag number?

Payne: Hold on, he’s driving away. Hold on. (short pause) It’s a red Dodge Dakota. (long pause) Hold on. (long pause) OK, so he is going west down (street).

911: Did you get the tag number?

Payne: No, but I’m catching up to him right now.

911: We actually do not want you to chase him. We just want you to be safe.

Payne: I understand. I understand 100%. I’m going to get the tag number, nothing else. I’m west going down the West Forest Parkway. (pause) I’m catching up to him. The radiator is broken and everything. I have no idea how he’s driving his truck, the way that it is. (long pause) OK, the license plate is RA4859.

911: OK. So, if you can go back to the location where the incident happened, because someone is actually on the way to you now.

Payne: OK, well, there’s a police officer there. But he is drunk, I’m not, I’m not, I’m sorry, I’m here to tell you, I’m not not going to follow him. Because he is going to cause another accident. So, I will stay behind him until officers get to us, but until then, I’m, I’m not moving.

911: Yeah, that’s what I want. I want you guys to go back to the location where it happened and an officer will be out there momentarily, OK?

Payne: (unintelligible) Stop!

Herring: You come over here.

911: Ma’am.

Payne: (unintelligible) Stop-stop! I’m on the phone with 911. Get out of the car! Get out of the car! I’m on the phone with the police! They want to talk with you! (angry) Get out of the car! (higher pitch, like a cry) Nooooo! Nooooo!

911: Ma’am!

(Unintelligible crying, banging sounds)

(pause) (popping sound)

Payne: Ma’am! Ma’am! He just pulled the trigger of my gun in my hand while he was — while he was — (unintelligible because 911 talks at same time)

911: You weren’t supposed to follow him.

Payne: He hit my car!

911: OK, you got the tag number.

Payne: There’s a police officer down the street. Tell him to come over here, now! He pulled the trigger of my gun after he attacked me! Tell the police officer to turn around (unintelligible) and come up here, immediately!

(pause) (unintelligible)

911: OK Ma’am, where are you guys located now?

Payne: (unintelligible) I don’t know. I don’t know. I don’t know.

Voice: (unintelligible)

Payne: I did it! (pause) Yeah, I know.

911: OK, Ma’am.

Payne: There’s a police officer here now.

911: Speak with him.

Payne: All right.

Closing arguments

Mr. Tucker’s closing was poor. He missed an opportunity to show the photos of Miss Payne’s injuries again. He missed the opportunity to suggest that the bruise on Mr. Herring’s chest might have been caused by the crash with the semi.

He was wordy and boring. When he described inconsistencies in the witnesses’ testimony, he was confusing. He emphasized many times that they had been waiting four years for the trial. This did not help prove Miss Payne’s innocence and only gave credence to Herring’s family’s claim that the delay was to protect Miss Payne. He did not adequately explain what reasonable doubt would be.

Matthew Tucker

Mr. Tucker noted that the gun’s trigger had never been tested for DNA and fingerprints. Then he made the unhelpful point that Officer Richie had taken the gun from Miss Payne with no gloves on, so the DNA on the slide could be the officer’s. That could have caused jurors to think Mr. Herring never touched the gun at all.

Mr. Tucker also made these points:

- Robinson and the 911 operator both encouraged Miss Payne to get the tag number.

- There were long gaps in the 911 call during which the operator knew Miss Payne was trying to get the tag, but did not tell her to stop. The operator said contradictory things — get the tag number, but don’t chase him.

- When Miss Payne said, “I’m not not going to follow him,” the police weren’t there yet, and Mr. Herring had already caused an accident.

- Some witnesses gave different testimony right after the accident compared to what they said on the stand.

- The autopsy showed that the bullet went right to left. That didn’t make sense for someone sitting in a driver’s seat being shot from outside.

- A witness said Miss Payne was pounding and punching Mr. Herring repeatedly, but the autopsy revealed only one bruise. Miss Payne had bruises on her neck and face.

- In Officer Richie’s bodycam footage, everyone is talking about what happened in a civil manner. No one seems afraid of Miss Payne, although she was supposed to be a dangerous person who just shot a man just because he was a bad driver.

- Miss Payne wanted Mr. Herring out of the car for good reasons. The car was smoking and it could be dangerous to stay in it. Herring could have gotten into another accident, hurting himself or others.

Toward the end of Mr. Tucker’s summation, he said, “This is not some killer. This is not some murderer. This is a young girl who got caught up in the wrong situation, with a good heart, and good intentions.”

He should have stopped there. To Miss Payne’s detriment, he blabbered on sarcastically: “She killed him because he was a bad driver. She was a bitch; she would not change her mind. But not Miss Payne. On the stand, all she said was that the man was inebriated.”

Nigel Hunter’s closing argument was sharp. She used a throw-away quote from Miss Payne’s testimony, a quote that barely registered with me when I heard it, a sentence that was just Miss Payne’s way of explaining that she was a good person: “I mean not that it has anything to do with it, but my entire life until I was 18 and my grandfather passed away, I was going to be a police officer.”

The quote was put up on a screen, quickly followed by a photo of Miss Payne pulling her gun out. Miss Hunter said, “And on May 7, 2019, she got her opportunity, and as a result, 62-year-old Kenneth Herring, who was unarmed and minding his own business, was chased down, detained, shot, and murdered . . . and she had the audacity to come here and take that stand and blame everybody else.”

Miss Hunter then reminded the jury that Miss Payne had admitted to Officer Richie that she shot Mr. Herring. “You don’t get the death penalty for committing a traffic infraction,” Miss Hunter said, “And you know how much entitlement you have to have to chase somebody down, detain them, jump out your car, and run toward a stranger — He didn’t know her! He didn’t know why she was approaching his car! — and demand that they do anything! He didn’t have to listen to her!”

Miss Hunter accused Mr. Tucker of trying to misquote and twist the words of the witnesses. Miss Hunter said all of the witnesses had one thing in common, they all said that Miss Payne was the aggressor. She explained away inconsistencies in their testimony, and projected onto a screen these words: “This is not a memory contest. These events happened nearly four years ago.”

She said Miss McCranny saw the defendant block Mr. Herring’s vehicle in. She talked about how witnesses said Miss Payne was irate and punched Mr. Herring. They remember her pulling the gun and shooting right away.

Miss Hunter was right when she reminded the jury that the 911 operator told Miss Payne not to follow Mr. Herring, but she got other parts of the 911 call wrong. She told the jury that the defendant said, “You hit my car” to Mr. Herring before firing her gun. Miss Payne actually said “He hit my car” to the 911 operator after she fired. The prosecution tried to show that Miss Payne’s motive for shooting Mr. Herring was that she was angry her car was hit. It’s more likely that Miss Payne first noticed the damage after the shooting.

The prosecution effectively used a PowerPoint presentation to show how the law is worded, and to connect evidence presented in the trial to all eight of the charges.

Miss Hunter told the jury that Felony Murder did not require intent or malice. There only needs to be a death caused during an aggravated assault. An assault is when a person attempts to cause a violent injury to the victim or places the victim in reasonable fear that he will receive a violent injury. Miss Hunter said when Miss Payne pointed a gun at Mr. Herring, that put him in fear of receiving a violent injury, and the shooting caused the death.

She explained the False Imprisonment charge by referring to Miss Payne’s interview with detectives, when she said, “I found an opportunity and I pulled in front of him and I stopped him.” She said Mr. Tucker had pointed out that Mr. Herring could have driven away by going over the sidewalk if he really wanted to, but the law says the victim has “no duty to retreat.”

The prosecution explained when deadly force in self-defense is justified:

- There is a reasonable belief that such force is necessary

- To prevent death or great bodily injury to oneself or a third person

- To prevent the commission of a forcible felony

The law on self-defense also says: “A person is not justified in using force in self-defense if he is the initial aggressor.” This is why the prosecution often referred to Miss Payne as “aggressive” or “the aggressor.” Miss Hunter stated that once Miss Payne blocked Mr. Herring’s truck, she was committing a felony, and since Miss Payne approached Mr. Herring first, he was entitled to do whatever he needed to defend himself.

The law also states that she is the initial aggressor “unless she withdraws from the situation and communicates to the other an intent to withdraw.” Miss Hunter put on the screen, “To allow an armed aggressor who confronts and (sic) unarmed non-threatening victim, to claim self-defense, when the victim struggles to disarm the aggressor, is contrary to common sense and contrary to law.”

Next, she showed a photo of Mr. Herring and said there was no reason why he shouldn’t be alive today, preparing to spend the holidays with his family and friends. But for the defendant’s action in 2019, he would be.

She said the jury could listen to calls and watch videos again while they deliberated, but “This is not a complex case.” Miss Hunter asked the jury to find Hannah Payne guilty on all counts.

Jury instructions

In the judge’s instructions to the jury, she read the laws on accident and malice murder. Miss Payne lowered her head and trembled as the judge read:

ACCIDENT: No person shall be found guilty of any crime committed by misfortune or accident in which there was no criminal scheme undertaken or intention or criminal negligence. An accident is an event that takes place without one’s foresight or expectation.

MALICE MURDER: The state must prove that the defendant caused the death of another person unlawfully and with malice or forethought. The killing must have been done with malice to be murder. Malice is not ill will or hatred. Rather, it is the unlawful intent to kill without justification. You may find malice when the circumstances show that the defendant acted with a deliberate intention to unlawfully take the life of another person. You may also find malice when there does not appear to be significant provocation and all the circumstances of the killing show an abandoned and malignant heart. The state does not have to prove premeditation. The state does not have to prove motive to prove murder.

Deliberations

Judge Scott offered to let the jury come back for deliberations the next day, because it was after 6pm, but the jurors decided to stay. They asked to view the very short Cameron Williams video again. Two men, who sounded black, asked if the video could be shown in slow motion, but the judge said she could not slow it down. The video was paused before and after the gunshot, at the jurors’ request. They also asked to see the bodycam video of Officer Richie, who showed up after the shooting.

Verdict

The jury deliberated for one and a half hours and found Miss Payne guilty on all counts. She started crying from the first guilty verdict. Mr. Tucker touched her shoulder after the verdicts were finished. He requested that the judge poll the jury, so the judge asked the jurors, one by one, if that was their verdict, “freely and voluntarily made.” They all said yes.

The foreman sounded like a black man. The men all sounded black. It was harder to tell with the women. There was one very quiet woman, who may have been the sole white juror.

Miss Payne looked at her mother as the jury walked out. Her mother nodded to her.

Can she appeal?

Hannah Payne has 30 days to appeal. She is probably too nice to think of this, but she may be able to base an appeal on ineffective council. Matthew Tucker is not a public defender, but he had a history of showing up late to court, which irritated Shannon Brooks Malone, the black judge who was originally assigned to Miss Payne’s November 2022 trial. The day jury selection was supposed to begin, Mr. Tucker did not show up. Miss Payne told the judge that her lawyer had a stroke. In spite of the medical emergency, Judge Malone was very angry. She decided not to go forward with the trial, since Miss Payne was not represented, but she told Miss Payne, “You need to seriously seek new council. I am going to find that Mr. Tucker is in contempt of court.” She also said she would file a grievance with the state bar because Mr. Tucker was doing a disservice to his client. Mr. Tucker did an interview from his hospital bed, saying it was not a disservice, and they had been waiting three years to go to trial. Judge Jewel Scott was assigned to the later trial. With Judge Malone publicly questioning his capability and with Mr. Tucker having suffered a stroke one year earlier, she could perhaps claim incompetent counsel.

After the verdict

Hannah Paine’s mother left the courtroom with two family members. She was so distraught that she almost needed help to walk to her car. After the car door closed, she began screaming loudly.

Hannah Payne’s parents

Tasha Mosley, the black female DA, said she didn’t think race played a part in this trial. “It’s easy to say ‘race,’ you know, it’s real easy because we have a black victim and a white perpetrator. But that’s too easy. We have to go down into the depth of the evidence and . . . This was just somebody was out of control, that had the audacity to think she could make someone do something that wasn’t within her power.”

Kenneth Herring’s sister, who testified that he was diabetic, told the media, “I had to come to every court appearance. I was here to hear her incessant wailing as though she had been shot. . . . The case was presented as it happened. The state did its job, and the jurors did their job.”

Victim impact statements and sentencing

The sentencing hearing was a few days later. Mr. Tucker arrived a half hour late and apologized. Miss Payne entered the room crying and cried throughout the hearing.

The judge sentenced Miss Payne on only Counts 1, 5, and 6. The law says the other counts merge with those. Before her decision, the judge heard victim impact statements. Kenneth Herring’s sister Vickie and brother Keith, gave standard victim impact statements, recalling memories with the deceased and saying how much they would miss him. Vickie Herring cried and told the judge how her brother called her “biscuit head,” because she loved their mother’s fresh-baked biscuits. She said she would never hear him say that again.

Another sister, Jacquelyn Herring, spoke with a solemn tone that one would expect from a grieving sister, but her memories of Kenneth Herring seemed very unpleasant. She started by calling him “the big brother that liked to boss us around.” He always called her “Doody,” because she was always “doing something, and that seemed to be a problem with him.” One Christmas, he asked her to stand in the street and she did so, not knowing that she was going to be a target for his BB gun. She still has the scar on her leg. “That would be the only thing I have to remember him by.”

She added, “He thought he could not only boss me, but boss my daughters, and they weren’t having it.” He told her adult daughter that because he was the oldest, they “had to abide by his rules. . . .” She said she would not visit her brother’s grave. Yet, she also acted as though she would miss him, and she asked the judge to give Miss Payne “death,” then corrected herself to say “life without parole.” The death sentence was not an option.

Hannah Payne’s boss, co-worker, and neighbor spoke on her behalf to request leniency. Her former co-worker, Melissa Morris, said the way Miss Payne was portrayed in the press and on social media made her lose hope in people. “She has been portrayed as a vigilante, a racist, privileged. . . . She didn’t see color. We’re taking a big step back in society with this.” It was only during these statements that the court heard about Miss Payne’s sweet nature and record of helpfulness.

Judge Scott sentenced Hannah Payne to:

- Life with a possibility of parole for Count 1 (Malice Murder)

- Eight years for Count 5 (False Imprisonment)

- Five years for Count 6 (Possession of firearm while committing a felony)

She will be eligible for parole after 30 years, but then will have to serve an additional 13. She is now 25, so she has no chance of being released before age 68.

Tragedy

This case was like other cases I have covered for AmRen. It has some similarities to the Kyle Rittenhouse case, but Mr. Rittenhouse had the advantage of clear video showing him being attacked, so a jury acquitted him.

This case is more similar to that of Travis McMichael, Greg McMichael and William Bryan, who were convicted of murdering Ahmaud Arbery in 2021. Both cases were tried in Georgia, and both involved well-meaning white people who tried to help the police after black men committed low-level crimes. Both Hannah Payne and Travis McMichael were armed. In both cases, the black man grabbed the white person’s gun, and there was a tug-o-war. Both ended with the black men dying of gunshot wounds. And both cases ended up with whites — who had lived honorable lives and had never been in trouble before — being sentenced to stiff prison sentences.

It’s a shame to have to tell whites to squelch their instinct to help, but the law does not consider good intentions. There is no white privilege. Call 911 and let the police do their jobs. Don’t become another tragedy.

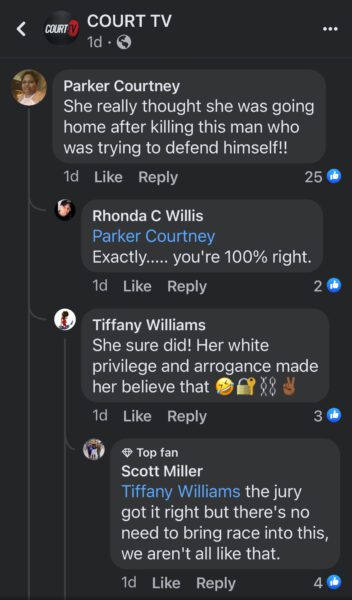

Comments on CourtTV’s Facebook page.