How It Got This Bad

Gregory Hood, American Renaissance, September 22, 2023

Subscribe to future audio versions of AmRen articles here.

Richard Hanania, The Origins of Woke: Civil Rights Law, Corporate America, and the Triumph of Identity Politics, Broadside Books, 2023, 288 pp.

If you build it, they will come.

That’s the message of Richard Hanania’s The Origins of Woke. It’s not that power defeats ideology, but that power, as expressed through laws, regulations, and court decisions, can spawn ideology. It’s a message American conservatives won’t like, and it’s therefore something they need to hear.

The American Right loves to expose, explain, and deconstruct the ideological evolution of the progressives who have been defeating the Right for the last six decades. Christopher Rufo’s America’s Cultural Revolution is the latest example. Pat Buchanan’s The Death of the West inspired campus radicals of my generation. The one time in my life I spoke to the late Andrew Breitbart, he credited William Lind’s views on Cultural Marxism as what most influenced his politics. Breitbart’s own maxim, “politics is downstream from culture,” is now a slogan for movement conservatives.

Top 6 books in “Cultural Policy” at Amazon are all Hanania and Rufo, and number 7 is something called “The War on Whites.” 😂

Feeling suddenly good about the future of the culture. https://t.co/gR96Z9WfX8 pic.twitter.com/I01465sBI7

— Richard Hanania (@RichardHanania) September 21, 2023

Richard Hanania tells us we’re wrong — and he’s probably right. He argues that critics of wokeness are blind to why these extreme beliefs have been all-conquering. “[W]hat I found strange about the anti-wokeness side of the debate was that its proponents seemed oblivious to the extent to which the beliefs and practices they disliked were mandated by law.” (vii) Dr. Hanania argues that Breitbart’s rule can promote political passivity, because “culture versus politics” is a false distinction, especially with a government that nearly dominates the economy.

The best part of this book for rightists should be its attention to concrete power politics and specific policies as laid down by courts and bureaucracies. Dr. Hanania cites James Burnham and notes that a managerial elite was inevitable but that “there was nothing inevitable about a portion of this class taking on social engineering as a career.” (67) The best leftist organizers, notably the notorious Saul Alinsky, would probably agree with him. Alinsky was famously dismissive of ideological purity, emphasizing appeals to interest while building coalitions. Politics is about power and transferring resources to your side, not about the ways policies express a political philosophy.

Dr. Hanania defines “three pillars” of wokeness: the belief that disparities can be explained only by discrimination, that speech must be restricted to overcome such disparities, and that a bureaucracy is necessary to “enforce correct thought and action.” The first two define whether a person or idea is woke, while the third shows how wokeness is enforced. Some may protest that this gives critical theory short shrift, but that’s the point. A historical perspective, he argues, “provides many reasons to doubt theories that blame any particular philosophy or religion for what has happened.” He instead emphasizes the “primacy of politics over ideology.” (9-10) “Long before wokeness was a cultural phenomenon, it was law,” he says, with the key to its success being its “hidden, indirect nature” because civil rights law “involves constantly nudging institutions in the direction of being obsessed with identity and suppressing speech, all while it speaks in the language of freedom and nondiscrimination.” (10) It’s deceptive and thus hard to combat.

Dr. Hanania cautions us not to indulge the conservative temptation to rage against the whole system, nor to believe the system was carefully constructed to be this effective. Instead, while legislators thought they were abolishing “a caste system in the South,” “politicians and government bureaucrats in institutions like the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and the Department of Labor” got around the text of the law to achieve equality of outcome. The Supreme Court banned race quotas but blessed the concept of disparate impact, arguably the worst possible outcome because it was so vague. “Nothing is explicitly allowed, or prohibited,” Dr. Hanania says.

Republicans — notably when Richard Nixon expanded affirmative action to government contracts and President George H.W. Bush signed the Civil Rights Act of 1991 — may have been worse than President Lyndon Johnson. Nixon gave protected categories (an ever-expanding group) special privileges, and the 1991 act expanded the scope of lawsuits and complaints of “discrimination” and “harassment,” and “disparate impact.” Republicans, even after the Republican Revolution, with the supposed conservative Newt Gingrich as Speaker, shied away from ending affirmative action when they had the chance. “Sometime in 1995,” Dr. Hanania says, “Republican leaders apparently concluded that winning the public relations battle over affirmative action was hopeless, and they stopped talking about the issue.” (168)

President George H.W. Bush signs the Civil Rights Act of 1991.

George W. Bush expanded the scope of disability cases even further, with the ADA Amendments Act of 2008 — and got an overwhelming bipartisan majority. In all of these cases, there was seemingly no thought about the long-term consequences of providing a rich market for activists and lawyers exploiting ethnic and other grievances, nor did “free-market” Republicans seem to consider the economic costs. Dr. Hanania argues that Republicans are growing more combative on these issues, even though “wokeness” is now a powerful force with well-funded activists and secure bases in academia and the media. The woke empire was created in a fit of absent-mindedness, at least at the highest levels.

“Diversity” — a value with almost religious importance in modern America — was the byproduct of Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr.’s opinion in University of California v. Bakke (1978), which permitted universities to consider race, while banning quotas. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg’s dissent, which mocked banning quotas but allowing the same goal “through winks, nods, and disguises,” was more coherent and honest. (13) Dr. Hanania says that in the years after the decision, diversity went from almost unmentioned to a major concept discussed in the press and then the standard justification for race preferences. “We can see the invention of a concept in real time.” (13) Where did it come from? “It was basically the creation of one judge acting out of either political timidity or intellectual laziness.”

Violence also works. Citing Hugh Davis Graham and John Skrentny, Dr. Hanania argues that inner-city riots convinced Washington “to go beyond color-blindness and adopt policies like affirmative action and minority set-asides in order to buy social peace.” (14) Bureaucratic decisions from decades ago also “determined which groups were protected and which were not,” leading to such absurdities as the invention of “Hispanics” (which includes white Spaniards) and calling Arabs “white.”

Perhaps the saddest and yet most symbolic example of government fumbling is the reason why “sex discrimination” is such a force in American law and culture today: Rep. Howard Smith (D-VA) inserted it into the Civil Rights Act as part of an effort to kill the bill because he thought people would think it too absurd. Legislators didn’t understand what they were unleashing. The lesson is that if the law opens a space, power will fill it and come up with an ideology to justify it, and that ideology will be driven to its logical conclusion, no matter how ridiculous. Those who have the tightest focus on the issue and the most to gain — the bureaucrats who administer the new rules — have little reason to restrain themselves.

The government decides which categories are relevant to public life, and which are not. It then goes about encouraging a system of data collection and record keeping to justify state intervention and private activism. Law influences culture, as individuals are financially incentivized to lean into accepted identities and play their assigned roles, and may come to genuinely believe that the box they are put in has deep historical, moral, and spiritual importance. All of this happens far from the democratic process; civil rights laws as passed by Congress, incomplete and vague, serve as the justification for bureaucrats and judges to remake society. (92)

We take identity categories for granted so often that we often fail to reflect on their arbitrary nature. Some may laugh at the author’s hypothetical example of French and Italian Americans calling themselves “Romance Americans,” but that’s less absurd than Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) being lumped together and giving us campaigns such as “Stop AAPI Hate.”

Different ethnic groups can be joined together or split apart depending on the financial and political incentives, but the arbitrary nature of the process doesn’t prevent ethnic activists from taking it very seriously. Addressing the “Great Replacement,” Dr. Hanania says that “what neither side seems to have noticed is that the idea of the great replacement derives from government racial classifications and their downstream effect on culture.” (105) Thus, Arabs and Persians are “white” and therefore slow the Great Replacement. Some “Hispanics” are white, but — statistically — speed the Great Replacement. None of this makes the issue less divisive.

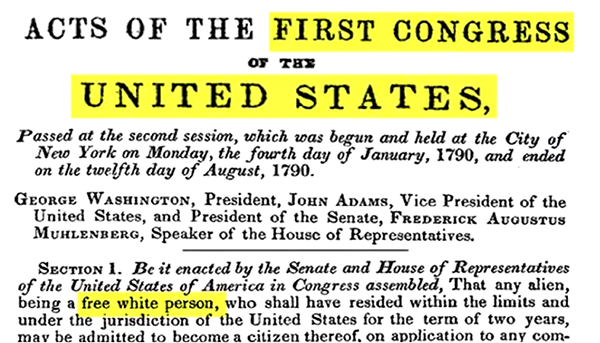

Is “white” as arbitrary and meaningless as “AAPI”? Many don’t think Middles Easterners are part of our race or civilization. White advocates would argue that “white” is not just a cultural but a biological category, and that the Founders wrote it into the 1790 Naturalization Act. But even if white identity were entirely arbitrary, The Origins of Woke shows that even small bureaucratic changes can produce sincere and emotional conceptions of group identity. If whites didn’t exist, the government could invent them — for purposes benign or malevolent. Dr. Hanania suggests that racial identities are likely to grow stronger with time.

Wokeness undermined representative government. What we call “civil rights” has little to do with what elected representatives thought they were voting for.

At various points throughout the debate over the Civil Rights Act, critics of the bill expressed concern that it might do x. In response, supporters of the bill would say, “no, it won’t do x,” and the two sides would agree to a compromise that involved entering a clause into the bill in effect saying that “x is prohibited.” Usually within a decade, the EEOC [Equal Employment Opportunity Commission] and the federal courts would do x anyway. (39)

Wokeness leads to tyranny. Dr. Hanania explains that with the concept of disparate impact, “basically everything is illegal and the government will decide which violations it goes after.” This just doesn’t invite corruption; it practically defines it.

Finally, wokeness makes us cowards. “Businesses must display ‘EEO Is the Law’ posters, which tell the world that an employer both practices affirmative action and does not discriminate based on race,” says Dr. Hanania. “Citizens are thus socialized to engage in doublethink, not question official dogma on sensitive issues, and walk on eggshells when faced with the demands of noisy activists within institutions, no matter how unreasonable they might be.” (22)

Dr. Hanania emphasizes that he is not attempting to track every way “wokeness as law” affects our lives, but for newcomers, he will seem exhaustive. A table provides the key doctrines (affirmative action, disparate impact in the private sector, disparate impact in government funding, anti-harassment law, and anti-harassment in women’s sports), the legal basis, what it does, the way it is enforced, and its effects. Another table shows what can be done to roll back some of these destructive policies. These tables are a greater accomplishment than entire books about the philosophical problems with liberal doctrines on race. Dr. Hanania’s detailed histories of the regulations, executive orders, court decisions, and laws (which are arguably the least important in determining what really happens) are invaluable.

Dr. Hanania’s thesis isn’t totally comprehensive. If we accept that seemingly minor battles birthed the swelling cancer of wokeness, we must still contend with its larger triumph throughout the entire Western world, especially the Anglosphere. The United Kingdom, New Zealand, and Canada are worse than America when it comes to meddling in social relations for the benefit of non-whites, and there seems to be less resistance to white shaming. The rest of Europe — certainly anything coming out of Brussels — isn’t much better.

Dr. Hanania notes that wokeness in France may even be stronger than in the United States because of hate speech laws, but there is more resistance to le wokisme (considered an American cultural invasion) in elite circles and arguably less regulation of everyday speech. However, wokeness is still advancing in France alongside demographic transformation, as well as in Germany, the Netherlands, and the rest of Europe. Dr. Hanania praises France for not collecting data on race or forcing companies to do so, but while this might pose an obstacle to “wokeness,” it hasn’t reversed or stopped demographic transformation or anti-white policies. We can accept that cultural change is downstream from politics, but everything is downstream from demography. Surging numbers of non-whites will lead to politicians willing to use race-based programs to win their support and electorally overwhelm whites. Why demographic change is occurring, who is behind it, and what they hope to gain are important questions.

Dr. Hanania frankly admits that his book is directed towards Republicans because Democrats refuse to talk about these questions. “While Americans debate taxes and foreign policy, culture and identity issues appear to be what is truly motivating many of the nation’s most prominent activists, media figures, and political leaders on both sides, along with the mass of their voters,” he says. (1)

Wokeness isn’t just a reflection of institutional incentives, although one could argue that ideology tends to follow interests. Mr. Rufo’s book may have focused on ideology, and such a history is needed to explain why activists were willing to use such aggressive tactics to get Ethnic Studies departments and other programs established even before the “woke” revolution really took off. The two books are often compared, and it’s probably better to read Mr. Rufo’s book first to learn how the movement first arose, while Dr. Hanania explains how it established itself within our system.

Dr. Hanania’s argument is that there is a solution to these problems within the system, but it requires action from people who can actually get elected, make policy, and appoint judges and staffers. This may happen because fewer Republicans care about being called racist. They can even fight “wokeness” by working with the original language and intent of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. (Dr. Hanania thinks repealing it is politically unrealistic.) Ron DeSantis’s presidential campaign — which looked more promising when this book was written — could be a herald, with his boast that the Sunshine State is the place where “woke goes to die” and his successful fights against DEI and ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) policies. Leading candidate Vivek Ramaswamy wrote a blurb for The Origins of Woke.

Dr. Hanania’s acceptance of political tribalism might be surprising to his Substack readers and his X followers. He is openly contemptuous of the downward mobility of the Republican base, the antics of anti-vaccine activists, and of Republicans who support Donald Trump because they want to be entertained. He has also written about the ways diversity really is a strength and sees no contradiction between accepting the reality of racial differences in IQ and wanting more immigration. He is what we might call a cognitive supremacist, who wants a meritocracy of the intelligent, market access to elite human capital (and therefore relatively loose immigration), and few drags on productivity and efficiency in the interests of equity (to please leftists) or of tradition and ethnic solidarity (to please rightists). Of course, he’s not saying political tribalism is good — it’s just the way it is now, and people who want to change policy must accept it.

We may think Dr. Hanania is wrong about some things. In fact, he’s wrong about a lot of things. However, someone who accepts the reality of the racial achievement gaps isn’t obligated to embrace white identity politics, let alone become a zealot. In turn, we are under no obligation to abandon our views because we agree with much of his thesis. What he wants for “wokeness” is what we want, and his criticism sharpens our thinking.

It may even be argued that only someone like him could write this book. If the price is simply a few sneers at white working-class voters or at the far-right, that’s a small price to pay for progress. When it comes to racial politics on the American Right, those who can do something won’t, and those who would do something, can’t. Someone who really understands the importance of these issues may become a public race realist or white advocate — which means forfeiting any chance of political, bureaucratic, or judicial office. In contrast, Republicans who are in positions of power are naïve or cowardly, desperately avoiding controversy, accepting leftist rhetoric at face value, and almost apologizing for their position. That is Dr. Hanania’s story. Dedicated left-wing judges, bureaucrats, and activists take any opportunity to expand their power and shift the culture. Republicans dreamily go along with it, thinking that they are being nice or, more likely, not thinking at all. I’d prefer that people who despise me but understand this issue be in power rather than people who pay lip service to our issues but are easily rolled.

But even if it is politically advantageous, will Republicans act? It requires a great deal of public pressure on a conservative to make him do the right thing, and changes to regulations and executive orders require dedication and detailed knowledge because the bureaucracy can’t be trusted. Conservative judges have already been a disappointment. “In contrast to disparate impact, affirmative action in college admissions has been in conservatives’ crosshairs for decades, and by the time this book is released, Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard may have already been decided,” Dr. Hanania says. (198) It has, and the conservatives did the same thing Dr. Hanania bemoans throughout the book: outlawed racial discrimination, while leaving loopholes that will let colleges keep discriminating by fiddling with racial identity statements and downplaying objective criteria for admission. Outright quotas would be more honest and therefore better.

Dr. Hanania’s assumption that anything can be done has therefore already taken a major hit; the conservative legal movement has already blown a priceless opportunity. Bureaucrats, activists, and institutions must be given no loopholes. The Origins of Woke amply shows why we can’t trust in their good faith or reasonableness.

Stopping highly motivated small groups who get large subsidies extracted from an easily distracted and ignorant population is a big problem for a democracy, even if it’s racially homogenous. Race makes things worse. Many non-whites think they are fighting a holy crusade against “racism” while whites, at best, are making a vague stand for individualism. An overall collapse in living standards doesn’t mean there will automatically be a successful reaction — Venezuela, Zimbabwe, and South Africa are proof of that. Sometimes things just fall apart and stay that way. Wokeness could grow to the point that it chokes the whole economy. Dr. Hanania himself once suggested a “strongman” might be a way out of the mess because “liberals always win,” but this also has costs and we don’t have a strongman. Dr. Hanania now emphasizes his support for liberal democracy and insists the system offers a path to victory for conservatives, who, he argues, actually have been winning on guns, homeschooling, and other issues.

“Wokeness” may be different. The question is whether conservatives really want to win on this issue, at least enough to withstand furious opposition from a campaign to roll back so-called “civil rights.” Gun owners and homeschoolers are more committed than the average person who wants to ban guns or homeschooling. With wokeness, it’s the reverse. The fight against it is a struggle for free speech, freedom of association, economic freedom, and the marketplace of ideas. Unfortunately, the media will never frame it that way and those who benefit from it will never surrender. White advocates have yet to find conservative leaders with the will to carry out policy changes. Defeating identity politics may require a countervailing movement of white identity politics.

Such a solution is unlikely to satisfy Dr. Hanania and he probably thinks it’s extreme and unnecessary. I hope he’s right and I’m wrong. The Origins of Woke may be best seen as a guide not to white advocates or even conservatives, but to liberals. It is an off-ramp for moderates who want to consolidate the civil rights revolution while reigning in wokeness before it generates a backlash in which white identitarians claim power. Rather than trying to cancel Dr. Hanania, they’d be wise to take his advice. If they don’t, we can take The Origins of Woke as a guide for where to begin, but certainly not where to end.