Slavery and Its Discontents

Jared Taylor, American Renaissance, March 3, 2023

Subscribe to future audio versions of AmRen articles here.

J. C. Furnas, The Road to Harpers Ferry, William Sloan Associates, 1959, 477 pp. (hard bound, out of print, but available used).

It has become such a fashion to deplore American slavery that liberals call it America’s “original sin.” We must despise any man who had anything to do with it, no matter how heroic or accomplished. Surely, George Washington will eventually end up in the doghouse, along with Robert E. Lee and Thomas Jefferson.

How recently were scholars writing balanced, academic studies of slavery? If you go back as far as 1959, you will find a remarkable book called The Road to Harpers Ferry, by J. C. Furnas (1905–2001). He was an independent journalist and historian, who was a middle-of-the road liberal for his time. Free of today’s compulsion to treat history like a morality play, he traced American slavery from the beginnings of the slave trade up to John Brown’s 1859 raid on Harper’s Ferry. He has many fascinating — and by today’s standards “racist” — observations, but his analysis of the motives of abolitionists is especially eye-opening.

Furnas leaves no doubt that John Brown was a charismatic crank verging on lunacy, but his portrayal of other abolitionists is just as scathing. Some were thoughtful, and they brought millions of Northerners around to abolitionism, but many were fanatics, motivated by what Furnas calls “100-proof hate.” Many didn’t seem to care much about blacks at all; they were driven by blazing fury against slaveowners and Southerners. Furnas — who was Yankee-born in Indianapolis and died in New Jersey — makes these people sound exactly like today’s crazed “anti-racists.”

It started in Africa

Furnas reports that a big part of the abolitionist view was a refusal to see the world as it was, and that a “paradisaical West Africa full of sweet-tempered primitives was a cardinal article of faith with early partisans of the Negro slave.” He counters this with contemporary accounts. Three hundred fifty years ago, a Frenchman called West African blacks “lewd and lazy to excess,” and another complained that “so slothful are the natives that if they have but one bad year, they are in danger of starving.” As an example of African simplemindedness, Furnas writes, “Dahomeyan royalty acquired twenty-odd cannon by purchase or capture, but never mounted them for use as artillery. They could go boom in prestige salutes well enough lying on the ground, touchhole up.” In defense of the Dahomey, anyone who has heard a black-powder cannon go off can imagine what a thrill it was for them.

And there were competently run kingdoms. The Ashanti “were as gold-greedy as any Spanish or English freebooter. They loved the stuff because it meant ready command of firearms and gunpowder for the wars that fascinated them, but also, miserlike, for its own massy, gleaming ductile brilliance.” Moreover, “early Europeans admired the intensive plantation farming of the well-organized Kingdom of Benin, where Negro grandees got much efficient work out of their gangs of Negro slaves.”

Benin Kingdom, warrior and attendants. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Credit: Julia Manzerova, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

“West Africans took slavery as much for granted as drumming,” writes Furnas. “Where people were property,” he adds, “it was natural to ‘pawn’ a child as security to be reared by the creditor and, if payment failed, retained as a slave or maybe sold in liquidation.” The Ashanti went on regular slave-catching raids, as if they were cattle roundups. They also practiced human sacrifice. In most other societies, it was to propitiate gods by offering them something valuable, but Furnas writes that Africans slaughtered slaves and prisoners to supply ancestors with servants in the afterlife.

Long-distance slave catching was rare because a long trek back to market could mean deaths along the way, which reduced profits. Moreover, “no buyer would look at the feeble, bony survivors until after costly feeding-up.” Stronger tribes therefore preyed on neighbors. Like the American Indians and the Māori of New Zealand, when the white man came, Africans never united to resist him; tribes hated each other.

The white man comes

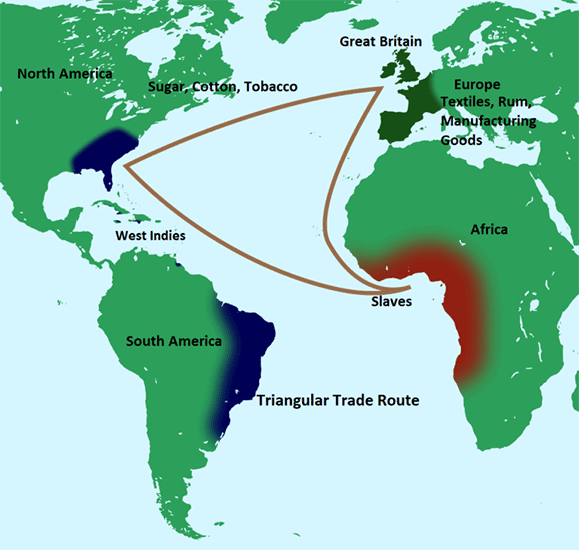

When whites began to explore the coast they found a ready-made network of slave-catching and slave-selling, and slaves became important in the triangular trade. In the age of sail, it was very hard for Europeans to beat against prevailing winds directly across the North Atlantic. It was much easier to follow the wind south to Africa and exchange manufactured goods for slaves. The next step — the middle passage — was to ride the easterly winds in the lower latitudes to the New World and exchange slaves for sugar, cotton, and tobacco; then run back to Europe on the northern westerlies.

The middle passage usually took seven or eight weeks, but could be made in as few as three.

When the trade began in the 16th century, slavers had to cruise the coast, picking up a dozen slaves here, a score there, and it took time to load. Later, slave-trading ports were established, where a ship could quickly load a full cargo of several hundred. This required fortifications to protect both slaves and landed European trade goods from African raiders. Europeans therefore built forts, such as Gorée in Senegal, and Anamabo and Elmina in Ghana. Elmina Castle was the first — and now the oldest — European-style building south of the Sahara, built originally by the Portuguese in 1482 for the gold and ivory trade.

Damien Halleux Radermecker, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

For Africans, there was no stigma to buying and selling people, but in Europe and America, slave traders were universally despised. Work on a slaver was a last resort for seamen. As for the trading stations, Furnas writes that “landsman enlisting with the monopoly companies as supervisors, armed guards or clerks, had to face years in festering West Africa, so those whom shiftlessness, hope of adventure, despair or ignorance induced to do so were probably even lower than slaver seamen.” As for captains, in 1786, the deputy town clerk of Liverpool said he knew only one “who did not deserve long ago to be hanged.”

Africans were happy to work for whites in the trade, and the Kru tribe of what is now Ivory Coast and Liberia had a high reputation for resisting slavery for themselves but cheerfully practicing it on others:

Slavery was all very well for non-Kru Negroes whom they fed, flogged, guarded and, as coastal deck crews on slavers, helped to exile. But slavery for Kru men themselves was unthinkable. They preferred to commit suicide or die of sheer chagrin or remain recalcitrant to a degree ruining all commercial value.

Furnas impolitely adds: “Had all West Africans resisted buy-and-sell slavery for themselves as sturdily as did the Kru, the United States would never have had a Negro problem.”

As many historians have noted, slavery in the United States was different from that of the rest of the New World, where owners imported men and worked them to death. Between 1712 and 1762, Barbados landed 150,000 slaves, but its slave population grew by only 28,000. The most profitable cargoes for the Caribbean were therefore men between the ages of 16 and 35 with a few women for house slaves. African middleman usually killed any males whom whites would not buy because it was a waste of money to keep unsaleable goods alive.

On the islands, few masters tried to convert slaves to Christianity, but in North America, Christianity greatly improved their treatment. Furnas notes that the West Indies were the worst possible places for slaves: They worked on huge plantations owned by absentee landlords who cared nothing for them, and were driven by brutal, third-rate whites. Furnas also notes that unlike in the American South, where slaves almost never worked bare breasted, in the West Indies, African custom prevailed, and some women wore nothing at all.

Today, much is made of the horrors of the middle passage, and a death rate of 15 percent on a voyage was not uncommon. However, many white crew and trans-Atlantic passengers also died. Furnas quotes what he calls “a fairly impartial observer [who] noted in the early 1800s that, thanks (he thought) to their being stowed naked and on a vegetable diet, the average cargo of slaves came ashore in the West Indies in better shape than the average unit of troops.” Furnas points out that it was good business to keep valuable slaves alive and healthy: “Whereas slaver captains and surgeons usually received small bonuses per slave landed, deaths at sea were profitable to emigrant ships, for emigrants paid fares in advance and no longer consumed provisions once their dead bodies had slid over side.”

Later in the trade, the British imposed limits on the number of slaves that could be transported, but: “[the rule of] three slaves to two tons of ship imposed by Britain in 1788 was the same ratio as that for British soldiers on transports 40 years later.” As for fraternization below decks, “the hands were supposed to stay away from the slave women, not for decorum, but to prevent quarrels. In well-disciplined ships the rule was observed.”

Just being in Africa was deadly for whites: “In 1825, a detachment of 108 British soldiers stationed in Gambia lost 87 men in four months.” Furnas notes that on the island of Fernando Po (now called Bioko and part of Equatorial Guinea), the death rate for whites was so high that the commandant always had two details constantly busy, one making coffins, the other digging graves.

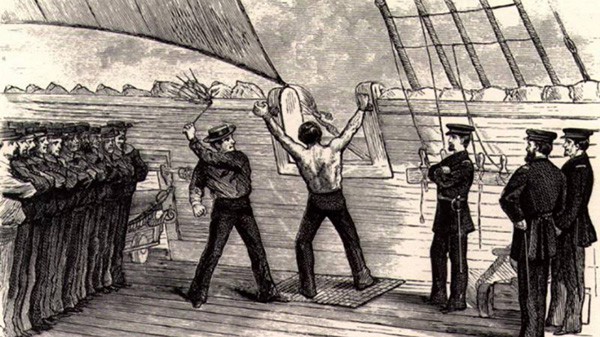

It is common to believe that whipping slaves was an unparalleled horror; far from it. Furnas points out that until the mid-1800s, flogging was standard discipline in all European armies. It was not abolished in the US Navy until 1862 and persisted in the British Navy until 1881. For the worst non-capital crimes, a British seamen could be “flogged round the fleet:” rowed to every ship in port where he got 12 lashes on each. In some cases, this was a death sentence.

Stopping the slave trade

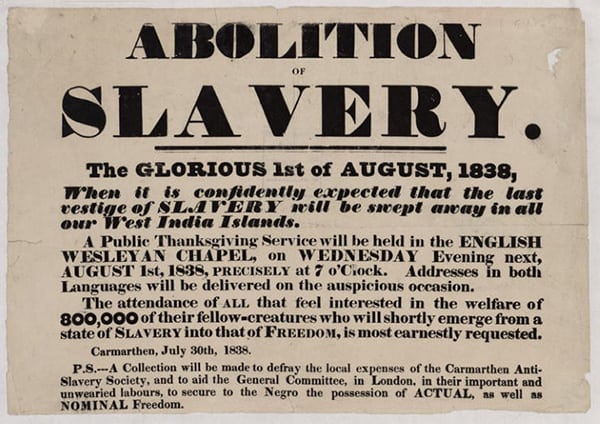

The British banned the slave trade within the empire in 1807 and the United States banned it in 1808. The British were much more vigilant in suppressing the trade than the Americans, and maintained a strong fleet off the West African coast. Almost all smuggled slaves went to Brazil and the Caribbean. They were so rare in the United States that in 1859, two freshly landed Africans were exhibited at the South Carolina State Fair as exotic curiosities.

British captains and crews won payments for catching slave ships, but until 1840, there had to be slaves found on board, which led to cat-and-mouse games. A slaver might hover off the African coast, waiting for a chance to dash in, take on a shipload of slaves, and sail away before a patrol arrived. If a British ship appeared, the slave captain quickly returned to port, unloaded the slaves and avoided arrest. In 1834, after Captain Richard Meredith of MHS Pelarus was foiled this way several times, he marched slaves back on board, declared the ship a slaver, and took ship and slaves to Sierra Leone, the haven the British had established for freed slaves. The shipowner sued for damages, and Meredith had to pay more than £1,000 — the equivalent of about 6-1/2 years’ pay. After 1840, under the “equipment clause” captains could confiscate an empty ship merely equipped with such things as manacle and a suspiciously large supply of food.

Capture by the British was not always a gift. A crew of navy men had to sail the ship up to Sierra Leone, but that was a difficult voyage against the wind. This could make the time at sea much longer than the anticipated middle passage, but with no extra food. Freedom for some slaves could mean emaciation or starvation for others. British sailors themselves were often hungry; ship’s rats were known as “midshipman’s rabbit.”

After 1820, slave trading was a crime for Americans — the equivalent of piracy — and carried the death penalty, but only one American slave captain, Nathaniel Gordon of Maine, was executed for it. He was hanged in 1860, after a career of running slaves to Brazil and Cuba, where the slave trade was still legal.

Abolition mania

The British abolition campaign was the first “social movement,” of the kind so familiar today. Dedicated people wrote tracts, gave lectures, preached from pulpits, and lobbied Parliament with the goal of ending, first, the slave trade and then slavery itself. One of the goals of ending the trade was to reduce the supply of slaves, who were commonly worked to death, in the hope that their value would increase and owners would treat them better. As in the United States, women were fervent, indispensable supporters.

In both countries, abolition was overwhelmingly Christian. Furnas describes the influential British abolitionists who became known as the Clapham Sect: “In their view, the principal reason for thinking West Indian slavery evil was not so much that it whipped and bullied Negroes — though that was a crying shame too — as that it denied their souls opportunity for salvation and tempted masters to cruelty and fornication.” It did not much matter whether abolition improved the lives of slaves; the goal was to convert them. Furnas offers abolitionist Thomas Buxton as an example of absurd piety. He was being driven in a coach at night when it overturned in an accident. He wrote:

As I was not injured, I did not feel in the slightest disturbed. I put on my spectacles, exchanged my cap for my hat, ascended through the broken window, and got upon the body of the coach, where I immediately delivered a lecture to the coachman on the impropriety of swearing at any time, but especially at the moment of delivery from danger.

American abolitionists worried that if the country persisted in slavery — which they considered a sin — America would be punished by God. “Hence so many abolitionists sounded as if they denounced slavery and slaveholders not so much because they felt for the slave’s miseries and valued his dignity and welfare as a human being as because to keep quiet would risk their own chances of personal salvation.” They believed that “the righteous man sins against God unless he makes every possible effort to reform erring brothers.”

Furnas argues that many abolitionists, Christian or not, were mentally unbalanced. The movement had:

An enticing savor of infallibility that attracted schizoid arrogance — a crucial ingredient in most crankishness — though often below the pathological level. It lent antislaveryism a greater appeal to those secretly proud of possessing the higher sensitivity, greater intelligence and social courage implied by their previous espousing of such glowing causes as phrenology and vegetarianism. The religious crank often added to the above theology a deep conviction that the end of the world was nigh and his battle against others’ sins had to be frantically intensified, lest the great day find him and his allies unfaithful stewards.

Furnas writes that “many an abolitionist of Old [John] Brown’s time thus piled multiple causes, some admirable, some freakish on one another, and combined antislaveryism with behavior that was, to say the least of it, neurotic.”

Abolition thus united legions of cranks: “Practically every reformer was antislavery . . . and conversely, Abolitionism derived much of its special momentum from the abnormally vivacious energies of the Reformers,” who were full of “wishful credulity, mistrust of objective reality, self-dramatization.”

They were like anti-racists today: all-purpose fanatics. Today, whatever else he is, every climate-change nut, militant nudist, Covid-commissar, story-hour drag queen, Antifa militant, anarchist, or Trotskyite is sure to be an anti-racist. And just like his psychological forebears, he is determined to force his views on everyone.

Abolitionists in both countries had abiding delusions. One was that slaves were noble innocents, chafing under the yoke, always ready to rise up for freedom. In Britain, there were several stage plays about idealized slave rebellion. One was called Three-Fingered Jack; another was Oroonok. These dramas firmly planted “the Negro-noble-savage-rebel in the pervasive cant of the day,” and spread the falsehood that whites went into the interior to capture Africans.

Abolitionists suppressed the fact that Africans had long enslaved each other and sold excess stock to whites. Likewise, in Jamaica, Suriname, and Saint Thomas, escaped slaves set up free villages in the jungle, but were not abolitionists. They didn’t lift a finger to help the remaining slaves.

For British and American abolitionists, the Haitian revolution was the model for what they hoped for elsewhere. Furnas notes that “the greatest effort that the Negro slave ever made in his own behalf, left his country ruined — ruined still to this day,” but abolitionists touted it as a great success. Haiti-as-black-paradise was at the top of “a long list of well-meaning fictions uttered by antislaveryites in the wishful belief that lies whiten in proportion to the righteousness of the liars’ intent.” In 1838, the American Anti-Slavery Society sent agents to Haiti to find data to prove that blacks could govern themselves. Their report was never published, no doubt because they found the opposite of what they looked for.

Furnas argues that abolitionism eventually veered from Christian duty into hatred: “Fervid reprehension of others’ sins leads almost irresistibly to sinner hating.” William Lloyd Garrison said of Southern congressmen: “We do not acknowledge them to be within the pale of Christianity . . . of humanity.” He called slaveholders “human hyenas and jackals who delight to listen to Negro groans, to revel in Negro blood, and to batten upon human flesh.” Abolitionists thrilled to every tale of slaveholder cruelty, real or imagined; it justified hatred.

The famous lady reformer, Angelina Grimke was once asked if she were not exaggerating the cruelty of slavery. She replied, “They cannot be exaggerated. It is impossible for imagination to go beyond the facts.”

For evidence of the near-insanity of some of the abolitionists, Furnas explains how Haiti assumed a new and different significance:

Hayti’s failure to stabilize herself gradually grew so glaring that fewer and fewer stateside antislaveryites, however careless about the facts, could respect the new nation. The immense impact of Hayti on them came rather from the blood-lustful assault of Negroes and affranchis [freed blacks] on the whites. These were taken to mean that a slave economy necessarily seethed with readiness to conspire and rebel; that such risings stood a good chance of success; that they inevitably meant looting, arson, torture, death and rape after the Haytian example.

One of John Brown’s backers was Thomas Parker, a deeply religious man, whom one of the leading abolitionists, Lydia Maria Child, called “the greatest man, morally and intellectually, that our country ever produced.” He wrote: “The fire of vengeance may be waked up even in an African’s heart, especially when it is fanned by the wickedness of a white man; then it runs from man to man, from town to town. What shall put it out? The white man’s blood!”

James Redpath was an abolitionist journalist who promoted John Brown and later wrote his biography. For him, there was no price too high to pay for freedom for blacks: “If only one man survived to relate how his race heroically fell, and to enjoy the freedom they had won, the liberty of that solitary Negro would be cheaply purchased by the universal slaughter of his people and their oppressors.”

James Redpath

Furnas writes of Garrison: “He never doubted that such a black army would gather [for insurrection] on summons. He felt only abstract revulsion from the bestial horror that he assumed would follow, slaves massacring whites, and then, with cumulative viciousness, whites massacring slaves as numbers and outside help began to tell.”

The most fanatical abolitionists came so to hate slaveholders that they regretted having even to live in the same country with them. Garrison began to despise the American nation itself because it countenanced slavey. The Union was “conceived in sin,” “brought forth in iniquity,” “a covenant with death,” “an agreement with hell,” a “refuge of lies.” Many abolitionists wanted to sever ties with the South because slavery was a disease “too deep for cure without amputation.”

Furnas argues that hatred of slaveowners became more intense than concern for slaves. He notes that Garrison didn’t care much for actual black people, and swindled free blacks to get ready money. Julia Ward Howe, a prominent abolitionist best known for writing the lyrics to “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” also thought slavery was so horrible that the South should be hived off. Yet, during a trip to the Caribbean in 1859 she wrote about blacks, whom she called “the raw material out of which Northern Humanitarians have spun so fine a skein of compassion and sympathy:”

The negro of the North is an ideal negro; it is the negro refined by white culture, elevated by white blood, instructed even by white iniquity; — the negro among negroes is a coarse, grinning, flat-footed, thick-skulled creature, ugly as Caliban, lazy as the laziest of brutes, chiefly ambitious to be of no use to anybody.

She added that the Negro’s nature was such as to suggest “the unwelcome question whether compulsory labor be not better than none?”

There are other reasons to doubt the motives of abolitionists. In the 1830s and ’40s there had been proposals for gradual and sometimes compensated abolition, but this annoyed abolitionists. As late as 1857, Elihu Burritt, a diplomat and reformer of considerable stature, called for federal action to free the slaves and compensate owners by selling federal land. Garrison called this “paying a thief for giving up stolen property, and not acknowledging that his crime was a crime.” Furnas writes: “Whether any such abortive schemes would have done well if tried in good faith is speculative. But Abolitionists’ consistent scorn of them does suggest lack of primary interest in slave-freeing.”

Certainly, there were decent, thoughtful men in the anti-slavery movement. Furnas admires Theodore Dwight Weld, for example, who opposed slavery on ethical grounds and neither exaggerated the horrors of slavery nor the abilities of blacks. He faced down hostile crowds, and was beaten up more than once. Still, Furnas writes that “the cranks’ high visibility made antislaveryism look at once ridiculous and incendiary.” He argues that Garrison, who fought with practically everyone else in the movement, became well known only because so many Southern papers cited him — sometimes unfairly — as the typical abolitionist. This only entrenched pro-slavery feeling in the South.

William Lloyd Garrison

Garrison was also unusual in insisting that freed slaves be treated as social and political equals, which also made him the perfect bogeyman for slaveowners. The vast majority of abolitionists opposed equality, and many wanted to “colonize” free blacks outside the United States.

Furnas argues that it was the screaming of men like Garrison and Redpath that began to make Southerners think there could be no compromise with the North. And then came the raid on Harper’s Ferry.

John Brown

“Old Brown,” as Furnas calls him to distinguish him from his sons, was clearly unhinged. He tried many businesses and failed in all of them, but he was good at making children: He had seven with his first wife, and after she died, produced 13 more with his second. It was finally as a violent abolitionist that he found his calling. He moved out to Kansas from New England and led gangs battling anyone who supported slavery. He raided their homesteads, stealing money, horses, cattle, household goods — anything of value. As one of his sons admitted years later, he supervised what became known as the Potawatomi Massacre. During the night of May 24–25 1856, his men hacked five unresisting pro-slavery men to death in front of their families.

Brown, steeped in the Bible and convinced he was God’s chosen instrument, had Rasputin-like charisma — at least for whites. Bronson Alcott wrote, “Our best people contribute something in aid of his plans without asking particulars. Such confidence does he inspire.” He was also a consummate showman. When he stayed with supporters, he ostentatiously checked his revolvers and rifles every night before going to bed, and warned his hostesses their carpets might be spoiled with blood: “You know I cannot be taken alive.” He rejoiced at the thought of slave insurrections and the massacre of whites. In different times, he would have been a Chinese Red Guard, a Bolshevik hitman, or an abortion-clinic-bomber.

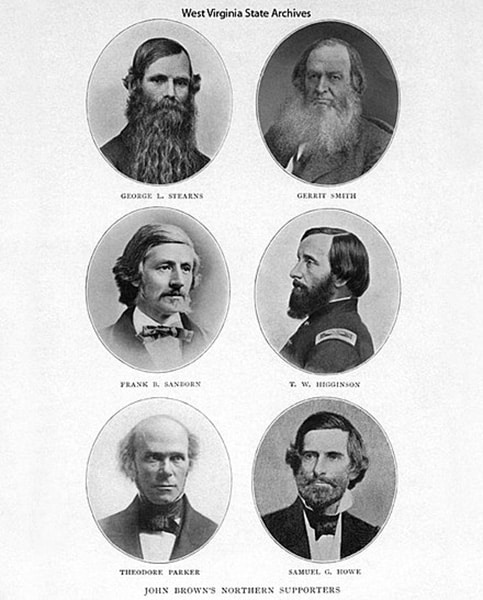

Brown cultivated rich and influential abolitionists, and his six main backers became known as “the secret six.”

He helped convince them that slavery must be ended with violence, and they helped him buy 200 rifles and 200 revolvers for slave insurrection. Brown also bought 950 pikes to distribute to blacks who were unfamiliar with firearms.

But he had had little success with blacks. Twice in 1858, with the help of Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass, he went to Canada to recruit free blacks for his fight to end slavery. They showed better judgment than whites; they thought he was a madman. His 21 Harpers Ferry foot soldiers included only one Canadian among its five blacks — along with three of Brown’s sons.

The scheme was insane from the start. If he was going to inspire blacks to revolt, his inability to recruit more than a handful should have given him pause. Furnas points out that American slave rebellions were often led by religious zealots: “In order to raise the slaves round Harpers Ferry, Old Brown should have enlisted some conspicuous local Negro preacher with religious delusions of grandeur as marked as his own.” Brown also chose a terrible place for the raid. There were few slaves in the area — hardly any plantation workers — and most were well-treated house servants. And Brown made no effort to alert and mobilize slaves. What Harper’s Ferry did have was a federal arsenal, but Brown already had more weapons than he could use.

The plan — so far as Brown had a plan — was to free enough blacks to establish a slave republic in the Allegheny Mountains, for which Brown would write a constitution, and where blacks would learn useful trades. But Brown waited until October to make his move; winter was the worst time to go camping in the mountains. Some historians think he wanted to head South, inspiring insurrections wherever he went.

The raid itself was comic — and deadly. The first man his gang killed was a free black man named Hayward Shepherd. The arsenal didn’t even have an armed guard, and was taken with ease. Brown should have loaded up weapons and left immediately. Instead, he took hostages and waited — no one knows why. His men holed up in a brick building and took potshots at citizens, killing six, including the mayor, and wounding five.

Two days later, US Marines under Robert E. Lee flushed the raiders out in three minutes, losing one man. They killed 10 of Brown’s men. Five escaped, and seven were caught, tried, and executed.

Aftermath

For Southerners, the Harpers Ferry raid was terrifying; what came later was appalling. After Brown was hanged for treason, people spoke of him as if, instead of killing unoffending strangers and planning to kill thousands more, he had piously laid down his life for the slaves in a hunger strike. Before he swung, Ralph Waldo Emerson said Brown “will make the gallows glorious like the cross.” Wendell Phillips said, “John Brown is the impersonation of God’s order and God’s law, molding a better future.” Henry David Thoreau wrote, “He is not Old Brown any longer; he is an Angel of light.” Once he had failed as an insurrectionist, Brown relished the prospect of martyrdom. There was widespread outrage in the North that he and his men should be executed for having taken up such a noble cause.

Journalist Edward House invented a story that Brown kissed a black baby on his way to the gallows. Last Moments of John Brown (1884) by Thomas Hovenden (1840–1895).

This was beyond comprehension in the South. If this was what Yankees thought, coexistence was impossible. Just as some abolitionists preferred partition rather than share a country with slavery, Southerners could not live with such people. Coming on the heels of the sanctification of a murderous madman, Lincoln’s election in 1860 pushed the South into secession. Thus, did Old Brown help set bloodshed in motion — surely enough slaughter of white men to satisfy his ghost.

Sisty-four years after publication, The Road to Harpers Ferry is as insightful and readable an account of the prelude to America’s greatest tragedy as any that today’s reader is likely to find.