Understanding Our Oppressors

Gregory Hood, American Renaissance, July 29, 2022

Paul Gottfried, Antifascism: The Course of a Crusade, Northern Illinois University Press, 2021, 209 pp., $31.26 hardcover, $12.99 Kindle

Every day, American Renaissance posts stories about racial double standards, hypocrisy, and progressives’ absurd positions. Many of our opponents are not just sincere but fanatical. Evidence can’t compete with moral fervor. Those who rule the West, and many of those they rule, truly believe in a creed that is blind. Dr. Paul Gottfried’s Antifascism: The Course of a Crusade explains what this creed is, where it comes from, and the myths we must dismantle.

The foundational myth, the creation story of the postwar West, is the need for all people to join the war against an ever-present “fascist” menace. This myth serves the interests of the ruling class and the moral yearnings of its servants. The myth is false but that doesn’t matter.

Most creation stories are false but necessary. They define good and evil, give direction, and are a way to view the world. Peoples can’t exist without myths. Neither can rulers. Most creation myths tell the tribe where it comes from, usually spawned by a divine ancestor. The West’s antifascist creation myth is different. It’s not about our origins and future, but about our shameful past and why we must be replaced. It’s a death cult.

Even though it is the eternal enemy, it’s hard to pin down what “fascism” is. Even during World War II, George Orwell said that “fascist” had essentially ceased to mean anything other than “bully” or “something we don’t like.” It wasn’t inevitable that fascism would become progressivism’s great enemy. Dr. Gottfried explains historical fascism.

“Although it is now widely believed that Mussolini and his authoritarian regime were merely a front for corporate capitalism and monopolistic landowners,” he writes, “this was far from universally believed in the 1920s or even into the 1930s.” (page 32) New Dealers were inspired by the Italian government’s “activist” measures. (35). Some early fascists even spoke of “proletarian nationalism.” When Mussolini declared war on France and Germany, he called his enemies “the plutocratic and reactionary democracies of the West,” in contrast to Italy, which was “proletarian and fascist.”

Two critical foreign policy decisions cost Mussolini his credibility with progressives. The first was Italy’s help to Francisco Franco’s nationalists, an obviously reactionary movement. The second was the alliance with Hitler. The latter cost Mussolini his regime and his life, and changed forever the way fascism would be viewed.

Credit Image: © Berliner Verlag/Archiv/DPA/ZUMAPRESS.com

For better or worse, fascism thereafter became associated with the traditional Right as well as Nazi Germany. Moreover, the term “fascist” was applied preeminently to Hitler’s Germany, which became the most significant representative of that ideology and form of government. Hitler and Mussolini exchanged visits to their capital cities, where they affirmed their shared ideological ground. Certain inconvenient facts went down the memory hole during these expressions of mutual admiration — that the early fascists were fanatically hostile to Germany and Austria, and that Mussolini, while celebrating “Latinity,” had often mocked Germans and their government as the “barbarians across the Alps.” (37)

Though we can discuss the differences between Italian fascism and German national socialism, they are interchangeable in pop culture and most academic discourse. Many even lump Francisco Franco or António de Oliveira Salazar of Portugal into the “fascist” camp, despite the great differences between these Catholic authoritarians and the European Axis powers.

The classical Marxist response to fascism — a movement that Marx’s scientific socialism failed to predict — was mixed. Friedrich Pollack argued that fascism was possible in more benign forms in countries like the United States, a concept that leads to the idea of the “managerial revolution,” developed by James Burnham (a former Trotskyist). (43). Marxists were divided over whether fascism was just another dictatorship, the inevitable conclusion of “totalitarian monopoly capitalism,” or something spawned by the development of the state. However, Dr. Gottfried writes that they agreed on one point: Hitler and Mussolini may have been tyrannical and evil, but they were acting rationally in pursuit of goals, however monstrous.

Dr. Gottfried argues that “Frankfurt School luminaries” including Eric Fromm, Theodor Adorno, and William Reich rejected the “narrowness of this approach,” instead focusing on the imagined “psychological underpinnings of anti-Semitism” and fascism, which included supposed “sexual repression and sadomasochistic abnormalities.” (47) It was this analysis that triumphed in the postwar West and defined the way antifascists would make sure fascism never happened again.

Postwar Germany was the first attempt to build an antifascist state. It used three strategies:

The three strategies were forced reeducation of the German people, the treatment of fascism as a form of pathology that required prolonged therapeutic treatment, and the production and distribution of pedagogical (that is to say, penitential) historiography emphasizing the disastrous results of living under a reactionary social order. Antifascists have typically favored using more than one of these three approaches. The evil they wish to combat is seen as so pervasive that countering it may require every available resource. Whichever the method to be applied, however, guilt and penance are the necessary accompaniments of the mind formation that antifascists are intent on fostering. (49)

Dr. Gottfried writes that postwar Germans got “harsh treatment from their conquerors,” including limitations on food, detention camps for hundreds of thousands of people, massive censorship, and the subjugation of East Germany by the Soviet Union. While the West let West Germany recover economically so it could contribute to the Cold War, Dr. Gottfried argues Social Democratic chancellor Willy Brandt (1969–1974) was a “transformational figure” who made “restitution for Germany’s history under the Third Reich” a renewed priority. The “Sixty-Eighters” — the New Left student revolutionaries who went on to positions of power — further emphasized the need for national penitence, even to the point of self-annihilation.

Dr. Gottfried even argues that some of those who supported (and still long for) the Communist dictatorship in East Germany did so not out of Marxism, but because it was “appropriate punishment for a nation that they hoped would ultimately disappear, through Third World immigration and/or absorption into an international body.” (57) He writes that “post-Marxist” antifascists are “critical of traditional social relations and cultural values, and they made common cause with the Marxist Left to finish off a world that disgusts them.” (57)

Dr. Gottfried says this form of antifascism was not German but American, or at least “German Jewish Marxists in American exile.” (47) The antifascist rot began here, or at least America was a safe place for the cancer to grow. Americans then imposed it on Germany, from which it spread to the entire West.

This is important because Western antifascism was not the same thing as Soviet Communism, and Dr. Gottfried notes the “growing irrelevance of Marxism-Leninism to our current politics.” (4) This is a problem for those who think Critical Race Theorists are “Communists” who want to restore the Soviet Union. Dr. Gottfried writes that the sexual and cultural obsessions of critical theorists such as Herbert Marcuse “raise persistent questions about whether the critical theorists ever represented orthodox Marxist teachings as opposed to Freudian-tinged cultural criticism.” (60) Modern conservatives who try to link Critical Race Theory, “Drag Queen Story Hour,” or modern antifa groups to the Soviet Union are kidding themselves. What we face is worse:

In certain respects, the intersectional Left and its antifascism are far more radical than any Marxist Left that preceded it. Unlike a merely socialist Left, which seeks to change the dominant form of production and to redistribute earnings under a powerful state, the newer Left is bent on revolution. It can never allow the crusade against fascist prejudice to come to a halt, lest this stasis permit a Hitler, Mussolini, or Donald Trump to reverse earlier reforms. It is also immoral and equally an invitation to fascism from this standpoint to treat any present moment as fixed and no longer subject to progressive transformation. Trump in the Untied States and the AfD [Alternative for Deutschland] in Germany were considered evil not because they wished to take us back to some distant past but because they refused to carry the cultural revolution forward. (134)

Dr. Gottfried writes that postwar antifascism was about “psychological reconditioning.” (59) This is important. If fascism comes from a psychological disorder and is a product of the “Authoritarian Personality,” it can occur anywhere, any time. World War II, in that sense, never ended. Winston Churchill, Charles de Gaulle, and other Allied leaders didn’t defeat fascism. They could have harbored fascist tendencies themselves to the extent they had traditional, patriotic, and authoritarian values. It’s no wonder Churchill may be enjoying his last years of respectability.

Russia is also a problem because Russians view World War II as the “Great Patriotic War,” not a victory over racism in a war that must continue within every human mind. On the surface, it seems absurd that both sides in the war in Ukraine claim to be fighting “fascism” and “Nazism.” However, it makes sense because both sides see “fascism” differently. To Russia, fascism was a threat to the Motherland that was overcome through patriotic service. To the West, nationalism of the Russian type is the heart of fascism. (137)

Dr. Gottfried’s writes that the “German template” of antifascism has been largely successful. Teaching people shame and self-hatred does not lead to a backlash. Most people believe what they are taught and may even take it farther. World War II is receding into distant memory, but Germans have moved “ever more directly toward antifascism as a state ideology.” “The remark by a former foreign affairs minister and violent socialist revolutionary Josef Fischer that Auschwitz is the founding myth of the German Federal Republic has become more, not less, true since German unification,” Dr. Gottfried writes. (54)

Seeing this “success,” Western leaders now think German reeducation is a “model for the reconstruction of other Western societies.” (58) It’s hard to disagree when just last year, the Washington Post published a piece arguing for treating America like a conquered nation. What America imposed on Germany is now being imposed on America itself, with an entirely negative national identity pushed from the top down. “[T]he media, culture industry, public administration, and state-controlled education all play pivotal roles,” Dr. Gottfried writes. (58) I would add that this enormous and never-ending effort in reeducation, deconstruction, supervision, and censorship also serves elite interests by justifying more funding and jobs for “anti-racist” educators, NGOs, watchdogs, security agencies, and others whose job is to police opinion.

Though Dr. Gottfried writes mostly about academia and journalism, there’s a lot of evidence for his argument in pop culture. Since 2016, television, movies, and video games have indulged the theme of a “Nazi” takeover of the United States. Sometimes, Americans collaborate with the Germans; in others, America itself is a kind of successor state or Fourth Reich. The Boys, The Man in the High Castle, Iron Sky, the Wolfenstein sequels, For All Mankind, Hunters, and countless other productions tell Americans that Nazis could be everywhere, even now. In 2020, David Weil explained Hunters this way: “The purpose of this show is an allegorical tale in many ways, to draw the parallels between the ‘30s and ‘40s in Europe and the ‘70s in the States and especially today with the racism and anti-Semitism and xenophobia, the likes of which we haven’t seen in decades. . . This show is really a question. It’s, ‘What do you do?’” In Hunters, needless to say, vigilantes heroically murder Nazis.

Nov. 25, 2015 – A controversial advertisement for the series ‘The Man in the High Castle’ on Third Avenue in New York. A subway painted in flags reminiscent of Nazi Germany was withdrawn after protests. (Credit Image: © Chris Melzer/DPA via ZUMA Press)

Dr. Gottfried argues that “Germany’s reeducation model,” now spreading throughout the West, goes beyond the notorious Antonio Gramsci and his proposed march through the institutions, which some call “Cultural Marxism.” Gramsci’s goal was to improve the well-being of workers. However, under today’s antifascism:

[T]he working masses are viewed as the bearers of deep-seated fascist and authoritarian attitudes. It therefore behooves the intelligentsia in alliance with the state to keep the ignorant and impulsive from exercising their unguided will. The success of democracy depends on acting illiberally in the short and middle term to prevent a fascist recrudescence. (58)

In other words, don’t call what’s happening Cultural Marxism. Don’t call those pushing it Communists. The Communists were far less extreme and didn’t hate and fear workers.

It’s in the interest of antifascists to give fascism and Nazism the broadest possible definition. This justifies everything they do. Dr. Gottfried analyzes Mark Bray, author of Antifa: The Anti-Fascist Handbook, a 2017 guest on Meet the Press, and one of the more honest antifascist theorists. Dr. Gottfried writes that “his underlying assumption is that we are already deep into a civil war between fascists and antifascists; therefore, the question of providing a platform for one’s adversary is no longer worth considering.” (84) Violence against “Nazis” is justified. “Our goal should be that in twenty years those who voted for Trump are too uncomfortable to share that fact in public,” Bray wrote. “We may not always be able to change someone’s beliefs, but we can sure as hell make it politically, socially, economically, and sometimes physically costly to articulate them.” (page 206, The Antifascist Handbook)

Dr. Gottfried argues that “by the 1990s antifascism had become an ideological pillar of the Western-style democratic administrative regime.” From a white advocate point of view, the state is constantly expanding its bureaucracy to fight invented problems such as racism, sexism, and transphobia, even to the point of waging “unconditional war on racism.” Dr. Gottfried notes that “however else it may operate, arousing a fear of fascism serves the interests of the powerful.” (1)

No self-respecting antifa activist would agree with that. The Mark Bray types think they are enemies of the state. This refusal to acknowledge power is a defining pathology of the modern Left. Leftists cannot conceive of themselves in power regardless of the corporate donations, state and academic sinecures, and adoring media they enjoy. How can you rebel against yourself? This makes it almost impossible to argue with these people.

Dr. Gottfried cites Hobbes to show this isn’t a new problem in politics. Many know that Hobbes argued for a sovereign to protect from anarchy, but Dr. Gottfried says that an authority figure “may also be required to settle the matter of what words mean.” (141) In our society, those who control media and public education hold this authority. They can define not just “fascism” but what constitutes “the science,” what is “hate,” and what, if anything, is a “woman.” While there’s been some conservative backlash, it may not succeed, especially among the “educated”:

A cultural lag can be observed in some rural areas or in what the French describe as “peripheral” areas. Nonetheless, those who go through the now-dominant socializing process come out with predictable opinions. The political party preferred by the college-educated young in Western Europe are the Greens, and Green partisans advocate a peculiar mix of positions: ecological discipline, deindustrialization, the opening of Western countries to Third World immigration, advanced feminism, and guaranteed LGBTQ rights. It makes no difference to their proponents whether these positions are internally inconsistent. (148)

Still, there is a moral code that drives antifascists, not just a grab bag of mindless slogans. “Our modern conception of democracy privileges pluralism and equality while rejecting social hierarchy and ethnic homogeneity,” writes Dr. Gottfried. He argues that modern “conservatives” essentially share these views. (149) Questioning equality itself puts one outside the parameters of polite discussion, which means politics is a pointless debate between the “authorized Left and the authorized Right” about who is more egalitarian.

Consider French “conservative” Nicolas Sarkozy, who said bluntly:

What is our aim? That aim is the mingling of races. The mingling of the races of various nations is the challenge of the twenty-first century. It is not a choice but an obligation. (150)

What about those who question why the world must embark on this absurd quest? “If peoples do not agree to this voluntarily, then states will have to impose this change by force,” he said. (150) One must respect his honesty.

The madness goes beyond equality. Dr. Gottfried argues that antifascists are consistent in seeing “identities as variable options open to individual choice.” (138) This extends to those things that would once have seemed insane, including transgenderism. We can expect even more bizarre behavior, including voluntary disabilities and amputations, or, as some already claim, being a different species.

“Paul Gottfried speaking with attendees at the Mises Institute’s 35th Anniversary Gala at the Hilton Midtown Manhattan in New York City, New York.” Photo credit: Gage Skidmore via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0

Dr. Gottfried notes that while antifa engage in “nihilistic violence,” what lies behind the rioting is not the belief that all cultures are equal but “moral anger.” They are not moral relativists. They have a clear moral vision, one stronger than most conservatives’ belief in God; they are willing to fight for it. Antifascists are, in Dr. Gottfried’s view, “waging a war for equality against particularity, in any traditional Western sense.” He writes that fascism was an attempt to affirm human nature, to unleash warrior peoples living in ancestral communities headed by a strong leader.

The antifascist state stands in contrast to the fascist one in the understanding of governance. It involves a sprawling administration, along with efforts to de-masculinize and de-ethnicize “populations,” a term favored by the German government officials of our time who do not want to be associated any longer with a “nation” or “Volk.” The antifascist regime operates with forces dedicated to fighting “hate” through mass media and public education. (137)

We shouldn’t underestimate the moral appeal. It’s the dark side of the Faustian quest for an identity without limits, without boundaries, and with perfect freedom. Identity is valid if chosen; illegitimate and arbitrary if not. “No gods, no masters,” as antifa say.

While progressivism and the current mania for mental disorders and invented genders seem insane, we should admit that this yearning for transcendence is rooted in Western history. We should also note that a society of deracinated individuals free to choose and discard identities at whim is perhaps the most consumerist identity one can imagine. That may explain Woke Capital’s relative complacency when antifa claim they are challenging capitalism itself.

Dr. Gottfried’s book helps us understand the system that rules us, the extremists who threaten us, and the moral framework that makes it all possible. I have a few minor objections.

First, anti-fascism wasn’t a response to fascism, even though fascism was a response to Communist revolutions. Strange as it may sound, one could argue that there was anti-fascism before fascism. Originally, “anti-fascism” was the new name Communist and socialist movements gave to what they had always done: oppose any political and ideological opponents. This one just happened to be one their theories hadn’t predicted. A revolutionary right-wing movement would not have arisen without a leftist revolutionary movement to oppose.

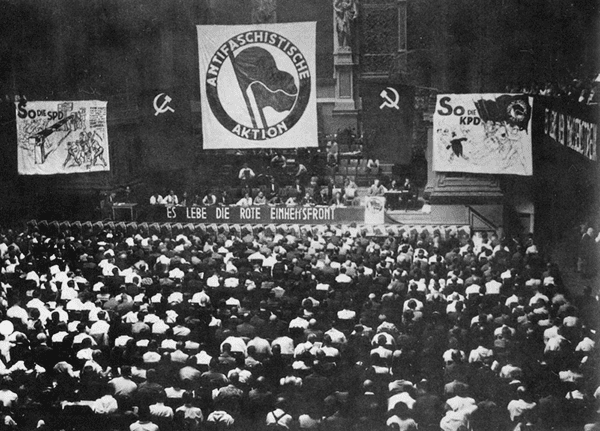

Scene from the 1932 Antifaschistische Aktion conference. Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Second, the book doesn’t fully use James Burnham and Sam Francis’s view of the managerial class to explain why antifascism has been so easily incorporated into Western liberal democracies, especially among corporate and government elites. It’s not just that some radicals wrote some books that people found persuasive. Postwar antifascism, by redefining fascism as a permanent political threat and a psychological pathology, is an ideological justification for more government power, regulation, and censorship.

Furthermore, while Dr. Gottfried argues that companies may contribute protection money to leftist organizations so they won’t be protested and boycotted, there may be more to it. Dr. Gottfried is right to observe that those with power benefit from a never-ending Brown Scare, but I would have welcomed more details about why they gain from it. We need to know so we can know how to fight antifascism. Without it, we can’t identify and replace elites who benefit from the existing system or cut off their sources of state and “philanthropic” funding.

Finally, there’s the problem of meeting the moral challenge. Dr. Gottfried argues antifascism is a central part of the system that rules us. We must advance a superior morality and way of life that scorns the “transcendence” antifascism supposedly offers. Instead of equality, promote greatness. Instead of permanent revolution, revere tradition. Instead of the transcendence leftists seek by choosing their identities, offer a different kind of transcendence — become who you are, become the highest exemplar of what you were born to be. Finally, instead of even considering chosen identities, point out that most people’s views are manipulated by media. “Choice” itself is something of an illusion, and that which is unchosen is superior. Of course, explaining antifascism is one book; explaining how to beat it is another.

Every page in the book is filled with brilliant observations and valuable information, but it isn’t organized systematically. That said, this is almost a strength. You can put the book down and return without losing your place or the flow of the argument.

Antifascism: The Course of a Crusade will give you a better understanding of the system that rules us. It should also scare you. One powerful quotation in the book comes from German novelist Uwe Tellkemp, who grew up in East Germany. He said that while Communist dictatorship was more direct, the “liberal democratic form of antifascism is physically less brutal but also more insidious: it takes over people’s lives internally until it swallows up ‘civil society.’” (99) Communism rots the body, but liberal democracy rots the soul.

Dr. Gottfried fears that because of its “ever-tightening control of cultural and educational institutions, liberal democratic antifascism in Germany may have become unstoppable.” Unless we can withdraw from, defund, and replace those institutions, Dr. Gottfried will be right not just about Germany, but the entire West. Optimism is cowardice, said Spengler. In that case, Dr. Gottfried is a brave man. His pessimism is an inspiration to all of us.