Jack London: Socialist and Racialist

Sinclair Jenkins, American Renaissance, January 14, 2020

Most Americans know Jack London as the man who wrote To Build a Fire. It is a simple story about one man’s attempt to survive the harsh Alaska winter, originally published in 1902 before being republished in its best-known version six years later. It is an excellent introduction to London — his writing, his interests, and his outlook on life. London’s literary world embodied Theodore Roosevelt’s ideal of the “strenuous life;” his tales always involve hard men battling either nature, the evil winds of fate, or dangerous enemies.

Jack London was more than just an adventure writer. During his brief life (1876 – 1916), London was a merchant sailor and a professional writer but also a revolutionary socialist. He wrote a book called How I Became a Socialist. Finally, London was a race realist. His heroes were always tough-minded white men, and London supported the white working-class of America — but only whites — against what he saw as the oppression of capitalism. London decried free-market exploitation of white workers:

Receiving $4.50 per day, because of his proficiency and immense working power, the American laborer has been known to scab upon scabs (so called) who took his place and received only $.90 per day for a longer day. In this particular instance, five Chinese coolies, working longer hours, gave less value for the price received from their employer than did one American laborer. [1]

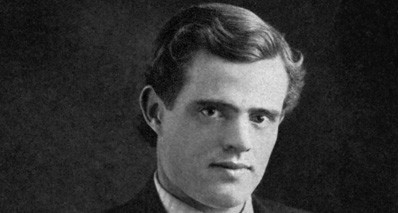

Jack London, portrait, 1905 (Credit Image: © Jt Vintage/Glasshouse via ZUMA Wire)

London, who came from the working class, knew why “a laborer is so fiercely hostile to another laborer who offers to work for less pay or longer hours.” [2] Faced with this kind of competition, the working man will have to give away “the food and shelter he enjoys” [3] in order to keep his job. In the age of globalization and mass non-white immigration, the problems London saw in 1904 have gotten worse. In our heartland today, working-class white men are dying “deaths of despair” because they cannot find work, are the demons of the pundit class, and swallow prescription drugs peddled by corrupt drug companies. London has a lot to teach us about living a masculine life and fighting for our convictions.

John Griffith Chaney was born out of wedlock on January 12, 1876 in San Francisco to Flora Wellman. Most historians think roving astrologer William Chaney was Jack’s father. Chaney wanted Flora to have an abortion, but Flora, who came from a family that settled in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the 17th century, refused. After Jack was born, she put him in the care of a black nurse and former Virginia plantation slave named Virginia Prentiss. Young Jack did not have a father figure — or a final surname — until Flora married a disabled Civil War veteran named John London.

The family moved across the San Francisco Bay to Oakland. Here, Jack began his informal education by reading library books and scribbling notes while sitting in Heinhold’s First and Last Chance Saloon. At age 14, Jack became a vagabond. He stole oysters and worked for a government fish patrol. He sailed to Japan as a merchant seaman. He rode the rails as a hobo. He marched with Kelly’s Industrial Army, one of several protest groups that formed Coxey’s Army, a body of unemployed workers who protested and demonstrated after the Panic of 1893.

At 19, London passed a four-year high school program in just one year. This earned him at spot at the University of California, Berkeley, but the young wanderer dropped out after a year to join in the Klondike gold rush. London failed to make his fortune and turned to writing. From then until his death at 40 in 1916, London earned a living writing poems, short stories, novels, and news stories. London embedded himself with the Imperial Japanese Army in Manchuria and was America’s top war correspondent during the Russo-Japanese War. He became convinced that the Japanese would try to push whites out of their colonies in Asia, and that the ultimate winner would be China, which he thought would become the world’s sole superpower by 1976. [4]

In 1910, London published his fanciful view of Asia’s future in an article called “The Unparalleled Invasion,” in McClure’s Magazine. China modernizes under the tutelage of the Japanese and then defeats them, going on to conquer Korea, Formosa, and other parts of East Asia. The Chinese then begin to threaten European colonies. Millions of Chinese (including fifth columnists) flood Hong Kong, Singapore, and the Dutch East Indies. Western powers, with the help of — surprisingly enough — the Ottoman Turks use germ warfare to kill millions of Chinese, ending China’s expansion. China recovers in 1982, when the European powers move in and mix “heterogeneously” with the naive Chinese. The result is a white-led mixed-race state. [4]

Jack London at his ranch. (Credit Image: © Mondadori Portfolio via ZUMA Press)

While London was covering the Russo-Japanese war, he wrote an article called “Yellow Peril” in which he wrote, “The religion of Japan is practically a worship of the State itself.” [5] This, London notes, is in contrast with the West, where whites are a “right-seeking race” because of Christianity. [6] London concludes with a warning: “No great race adventure can go far nor endure long which has no deeper foundation than material success.” Furthermore, “race glorification” is not enough either; something more is needed in order to dominate the globe. [7]

Elsewhere in his fiction, as in the novel The Mutiny on the Elsinore, he writes vividly about race differences and race pride. The narrator is a passenger on board the Elsinore, when its non-white and mixed-race crew mutinies. He joins the officers in resisting mutiny and they hold out against attack for days. The captain’s daughter is with them, and the narrator falls in love with her. The mutineers offer not to harm them if they surrender, but threaten mayhem if they hold out:

[A]cross my brain flashed a vision of all I had ever read and heard of the siege of the Legations at Peking, and of the plans of the white men for their womenkind in the event of the yellow hordes breaking through the last lines of defense. . . .

And I knew anger. Not ordinary anger, but cold anger. And I caught a vision of the high place in which we had sat and ruled down the ages in all lands, on all seas. I saw my kind, our women with us, in forlorn hopes and lost endeavours, pent in hill fortresses, rotted in jungle fastnesses, cut down to the last one on the decks of rocking ships. And always, our women with us, had we ruled the beasts.

But London understood the precariousness of the white man’s position:

Yes, I am a perishing blond, and a man, and I sit in the high place and bend the stupid ones to my will; and I am a lover, loving a royal woman of my own perishing breed, and together we occupy, and shall occupy, the high place of government and command until our kind perish from the earth. [8]

This is a strange sentiment for a socialist. The socialists of London’s day hated European imperialism, but London thought imperialism was a natural consequence of the superiority of the white man. For him, socialism was the best form of government only for higher men — for white men.

Although London read Karl Marx, his socialism was unorthodox. His 1908 novel The Iron Heel is set in a dystopian America ruled by an oligarchy. Its socialist revolutionary hero Ernest Everhard is one of the most explicit “overman” characters ever to appear in fiction. In the novel, he is described as a “natural aristocrat” and “a blond beast such as Nietzsche has described” [10]. London’s contemporary, H.G. Wells, also made the case for an elite “samurai” class of scientists and engineers as the vanguard of socialism in A Modern Utopia. This movement presaged fascism, which had roots in a strand of Nietzschean Socialism of the early 20th century.

Nietzschean Socialism, despite its apparent contradictions (Nietzsche called socialism “the tyranny of the least and the dumbest”), made sense to men such as London for whom the class struggle was a masculine affair that would be won only by strong and intelligent “natural aristocrats” fighting on behalf of the wage slaves of Europe and North America.

Modern dissidents cannot but admire London’s heroes: vigorous white men who fight for the “common man” or against the elements. We, too, should follow natural aristocrats among us who have a coherent vision of a future for our people. And of course, like London we should be realistic about race. London saw long before many others that East Asia would challenge Western hegemony. Well over 100 years after “Yellow Peril,” Americans are waking up to the threat.

Politics aside, London is a joy to read. He was a great writer who never had to rely on politics in order to tell a good story. He lived a life of adventure and of service to the common man. He was self-made and all-American, and he never lost sight of the importance of race.

* * *

[1]: London, Jack, “The Scab,” The Atlantic Monthly, January 1904.

[2]: Ibid.

[3]: Ibid.

[4]: Metraux, Daniel A., “Jack London Reporting from Tokyo and Manchuria: The Forgotten Role of an Influential Observer of Early Modern Asia,” Asia Pacific: Perspectives, Vol. VIII, No.I (June 2008), 2.

[4]: London, Jack, “The Unparalleled Invasion,” The Strength of the Strong, www.london.sonoma.edu.

[5]: London, Jack, “Yellow Peril,” Revolution and Other Essays, www.london.sonoma.edu.

[6]: Ibid.

[7]: Ibid.

[8]: London, Jack, The Mutiny on the Elsinore (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1914): 353.

[9]: London, Jack, “Letter of Resignation from the Socialist Party, Honolulu, Hawaii, 1916 March 7.

[10]: London, Jack, The Iron Heel (Norwood, MA: Norwood Press, 1908): 6.