Kenya’s National Hero: A Terrorist

Sinclair Jenkins, American Renaissance, May 31, 2019

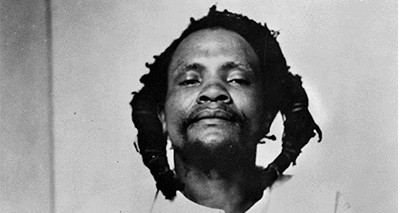

The closest thing to a national hero in Kenya is Dedan Kimathi. In addition to a giant and unattractive statue of him on Nairobi’s Kimathi Street, his name adorns Nyeri’s largest university. Kenyan men, especially those belonging to Kimathi’s own Kikuyu tribe, are encouraged to be like the man who fought the British during the Mau Mau Rebellion of the 1950s.

A protester carrying a placard standing next to the statue of Dedan Kimathi. Protesters took to the streets to call the government to arrest people involved in massive corruption scandals. (Credit Image: © Allan Muturi/SOPA Images via ZUMA Wire)

The larger-than-life version of Kimathi — freedom fighter, intellectual, and martyr — is nowhere to be found in Ian Henderson and Philip Goodhart’s Man Hunt in Kenya. Published in 1958, this slim, action-packed volume describes how Henderson and a handful of Europeans (mostly British men born in Kenya) turned black, former anti-British terrorists into “pseudo-gangs” to destroy Kimathi’s guerrilla network. When not describing the verdant splendor of British Kenya, Henderson describes Kimathi:

The British withdrawal from India had a profound effect on Kimathi, and he was also aware of the Egyptian terrorist activities in the Suez Canal Zone. He knew of the existence of the Soviet Union, but the theory of Communism and the subtleties of dialectical materialism meant nothing to him. He did, however, know the Bible as well as many lay preacher. . . . He spoke in parables, and his harangues were larded with allusions to and quotations from the Bible.[1]

This may make Kimathi sound like any crazed street preacher, but he was the most vicious and powerful leader of the Mau Mau rebels. As a young man, Kimathi had imbibed the anti-white rhetoric of Jomo Kenyatta’s Kenyan independence movement, plus Kimathi’s version of Christianity saw him at the center as an African christ. He also firmly believed in the ancient Kikuyu religion, but did not respect tribal elders he considered subservient to the British. Kimathi took his rebellion to the mountains and forests, where he murdered several followers. It was the job of Henderson and his men to hunt him down.

Ian Henderson

Henderson was raised in the White Highlands of Kenya’s Great Rift Valley. His family were Scots immigrants, and his father Jock served with the British irregulars in the guerrilla war in German East Africa.[2] Ian inherited his father’s rugged spirit, and he spent most of his youth tending the family’s farm and exploring the lush forests around it. At age 18, as the Second World War was ending, he volunteered for the British Colonial Police. His physical fitness and knowledge of the Kikuyu language made him invaluable after the Mau Mau uprising broke out in earnest in 1950.

The origins of the Mau Mau movement are not entirely known, nor is its name clearly understood. In Man Hunt in Kenya, Henderson and Goodhart are convinced that the movement was either created or directed by Jomo Kenyatta and the Kenyan African National Union party.[3] Other historians rarely make this claim, but most want to blame all the violence on the British anyway. All observers do agree that the Mau Mau loathed the British and all white people, and saw violence as the easiest way to gain independence for the Kikuyu.

The first members of the Mau Mau secret society were trade unionists and radical students from the cities of Nairobi and Nyeri. These militants moved into Kikuyu settlements and took part in oath swearing ceremonies that included animal fat and blood, promises to rid Kenya of Europeans, and allegiance to the Kikuyu god Ngai. To break this oath meant death. To oppose the Mau Mau or its goal of black power in Kenya also meant death.

In 1952, Commissioner of Police Michael O’Rourke, a battle-tested veteran of the Palestine Police Force, became aware of new Kikuyu oath ceremonies in the Rift Valley and the Nairobi area that required adherents to be willing to kill whites. The great paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey, also a native of British East Africa, heard Christian hymns sung at these ceremonies, though in praise of Kenyatta rather than Jesus.[4] White settlers mostly ignored these warning signs.

Many lived on lush farm lands in the central uplands, which became known as the White Highlands because non-white settlement was restricted. While the Happy Valley Set drank, took heroin, and fornicated in their well-maintained farm houses, the Kikuyu majority of Kenya seethed with the type of indignation that comes from landlessness. Resentment boiled over in 1952.

At first, the Mau Mau killed and disemboweled sheep and cows that belonged to European farmers. The first important murder was of Senior Chief Waruhiu Kungu, a Kikuyu chief the Mau Mau considered a traitor. Militants dressed as police officers gunned him down in his car seven miles outside of Nairobi, in an assassination that forced Governor Evelyn Baring to declare a state of emergency in the colony. This declaration meant British officials could start joint police and military operations, along with “villagization” campaigns, in which Kikuyus were put in detention camps.

The villagization campaign (which had been a great success against Communist insurgents in British Malaya) did not stop Mau Mau killings. On September 23rd and October 3rd, 1952, Mau Mau stabbed two British women to death at their farm near Thika.[5] In January 1953, approximately 30 Mau Mau killed the Ruck family — farmer Roger Ruck, his pregnant wife, and their six-year-old son — in their Rift Valley home. Newspapers reported that the family had been “slashed with pangas,” a type of heavy knife favored by the Kikuyu; it later became known that the assailants took their time hacking up their victims. The Rucks ran a hospital for local Kikuyu.

Other European victims included an 83-year-old who was clubbed to death, and Gray Leakey, the cousin of Louis Leakey. Gray was a fluent speaker of Kikuyu who had represented Jomo Kenyatta in a trial. Mau Mau entered the family home in North Nyeri, strangled Mrs. Mary Leakey, disemboweled the family’s Kikuyu cook, and took Gray up into the forests of Mount Kenya. There they ate parts of his body and buried him alive upside down.[6] In total, the Mau Mau murdered 32 Europeans, many more Asians (a majority of whom were Indians), and thousands of Africans. The worst Mau Mau atrocity was the murder of about one hundred Kikuyu, many of whom belonged to the pro-British Kikuyu Home Guard.

Chaos on this scale required more than a state of emergency. In late 1955, the police drew up a plan to capture and turn former Mau Mau terrorists into pro-government fighters. Known as pseudo-gangs, these former Mau Mau and their European officers went deep into the bush to track down small, often semi-independent Mau Mau groups. Henderson and his men excelled at this type of warfare. In Man Hunt in Kenya, Henderson describes the work it took to “flip” terrorists and turn them into allies.

“Kikuyu tribesmen working as members of a counter-gang tracking down Mau Mau insurgents.” Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205191317

Sometimes Kimathi himself made this easy because of his brutal leadership style. He beat or strangled anyone accused of spying for the British or of trying to seduce his wife. In other instances, Henderson leveraged Kikuyu superstition against Kimathi, who himself used witch doctors and the like to keep his soldiers in line. Much like the Simbas of a later war in the Congo, the Mau Mau fighters believed in omens, prophecy, and the promises of local conjure men who invoked the blessings of tribal gods before starting on military or cattle raids.

Henderson tried to draw Kimathi out of hiding in 1956 with coded letters left behind in Mau Mau mailboxes, which were nothing more than designated trees. When this failed, Henderson coated his face in shoe polish and burnt cork and tried approach the Mau Mau leader. This failed too, for unlike the Mau Mau, Henderson’s body knew the texture and smell of soap. After one dust-up, Henderson and the other Europeans dropped the idea that they could ever pass as Africans. Most of the time his men battled rain and animals, but when they ran into foraging Mau Mau, they killed or captured them.

As for Kimathi, he grew increasingly paranoid. Near the end, in 1956, he spoke often to his few followers about strangling his wife and committing suicide on top of Mount Kenya. On October 21, 1956, after Kimathi ran away from a British and Kenyan patrol, a member of the Kikuyu Home Guard shot him.[7] The British treated his wounds and put him on trial before an all-black jury. It found him guilty, and on February 18, 1957, Kimathi was hung inside the Kamiti Maximum Security Prison. No one knows where he is buried.

The man most responsible for bringing Kimathi to justice was far off in Nairobi on the day Kimathi was captured; Henderson and his wife were being introduced to Her Royal Highness, Princess Margaret, at a garden party.[8] Henderson continued to be the toast of Kenya (or at least white Kenya) until the nation became independent in 1962. The new black government of Jomo Kenyatta deported him.

Although the British Empire was all but gone in 1962, Henderson still had the imperial dream. Rather than retreat to “Little England,” he stayed abroad, and in 1966 was named the head of security for Bahrain. Henderson held this post until 1998, but earned the nickname “the Butcher” for supposedly authorizing the torture of political prisoners. He was a hero only from 1956 to 1957. For the rest of his life he was a villain: slayer of Kimathi and brutalizer of Gulf Arabs.

Many blacks, including Nelson Mandela, who was himself a terrorist in the Kimathi mold, praise Kimathi as an African Joan of Arc. In fact, he was something of a Trayvon Martin or a Michael Brown on a grander scale. He murdered far more Africans and Asians than Europeans and was bested by a farm boy-turned-police-officer.

Kenya’s traditional dancers seen performing during a commemoration of the Mau Mau. (Credit Image: © Billy Mutai/SOPA Images via ZUMA Wire)

* * *

[1] Henderson, Ian and Philip Goodhart, Man Hunt in Kenya: The Termination of a Most Bizarre and Violent Terrorist Organization (Toronto, New York, London, Sydney, Auckland: Bantam Books, 1988): 18.

[2] Henderson and Goodhart, 24.

[3] Henderson and Goodhart, 3.

[4] Van der Bijl, Nicholas, The Mau Mau Rebellion: The Emergency in Kenya, 1952-1956 (Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword Military, 2017): 43.

[5] Van der Bijl, 48.

[6] Anderson, David, Histories of the Hanged: The Dirty War in Kenya and the End of Empire (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2005): 117.

[7] Henderson and Goodhart, 227.

[8] Ibid.