Tough Guys, Honest Opinions

Sinclair Jenkins, American Renaissance, August 11, 2017

Most readers in the 1920s thought that detective fiction meant cozy drawing rooms, antique dueling pistols, and the cool fields of England. It belonged mostly to female writers such as Agatha Christie, Margery Allingham, and Dorothy L. Sayers. These women all came from comfortable middle-class backgrounds. Sayers herself doubled as an academic who translated Dante’s Divine Comedy into English during the height of her fiction career.

The detectives in these novels were eccentrics who specialized in arcane knowledge. Christie’s Belgian fop, Hercule Poirot, is what we would call a “foodie,” and he had a passion for fine clothes. Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey was a monocle-wearing aristocrat who collected arcane trinkets. These men did not solve overly gory cases or even get their riding gloves dirty. They solved locked-room puzzles that were like chess games or math problems.

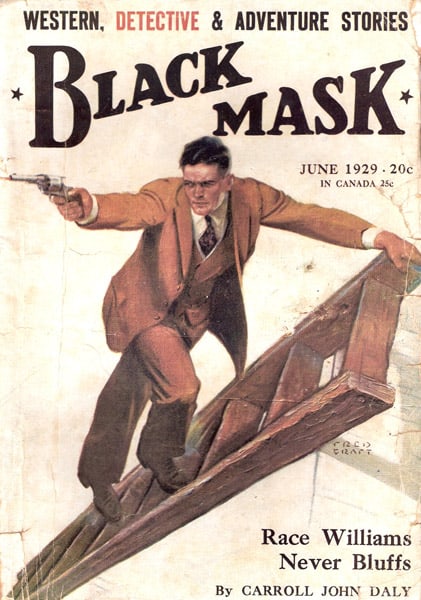

A reaction against this was inevitable. “Hardboiled,” — a thoroughly American style — emerged just as Britain was in its “Golden Age of detective fiction.” The most famous writers of the American style were Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and James M. Cain. However, the man most responsible for creating the genre was the overlooked Carroll John Daly. In 1922, Daly wrote the first hardboiled private-eye story, “The False Burton Combs,” and introduced the first-ever hardboiled private instigator: Race Williams. The first Race Williams story highlighted what makes hardboiled writing so different from the cozy mysteries of Christie and Co.: race consciousness.

While British detectives — all of whom take their cues from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes — have long dealt with corrupt whites from the colonies, native assassins, or immigrant anarchists from Italy or Russia, American writers had a street-level race consciousness.

The Daly story, “The Knights of the Open Palm,” sees gumshoe Williams fighting the Ku Klux Klan. The cynical Williams dislikes the Klan, and ultimately he triumphs over the corrupt politicians who run it. However, Williams does not hate the Klan because he believes in racial equality. Williams, the embodiment of New York City’s immigrant working-class, was just not keen on any type of WASP supremacy.

Sean McCann pointed out in his book Gumshoe America that the Klan of the 1920s supported a social worldview that aligned well with the hardboiled ethos. Klan supporters “railed against class parasites and social decadence,” and thought that urbanization promoted degeneracy. Williams clearly agreed with such sentiments. So did Dashiell Hammett’s “Continental Op,” an unnamed, stocky private detective who may have been based on a real Pinkerton detective that Hammett worked with in Baltimore. Both these fictional detectives walked the filthy American streets, thick with blackmailers, thieves, and murderers.

“The Knights of the Open Palm” appeared in an issue of Black Mask dedicated to discussing the Ku Klux Klan. The magazine’s mostly working-class readers wrote in with pro-Klan and anti-Klan opinions, all of which saw print. From the beginning, the hardboiled revolution reflected America’s racial politics.

On a more obvious level, men like Hammett and Chandler wrote stories about tough white men who have to confront a multi-racial underworld. Chandler, who picked up the crown from Hammett, puts his detective, Philip Marlowe, in the middle of a black bar in his novel Farewell, My Lovely (1940):

The chanting at the crap table stopped dead and the light over it jerked out. There was a sudden silence as heavy as a water-logged boat. Eyes looked at us, chestnut colored eyes, set in faces that ranged from gray to deep black. Heads turned slowly and the eyes in them glistened and stared in the dead silence of another race.

Marlowe and another white man with him know they are unwanted in Watts. Their intrusion ends in a mini race riot between them and the bar’s patrons. Such scenes are common in Chandler’s writing, especially when the whiteness of his heroes can be contrasted with the non-whiteness of their adversaries.

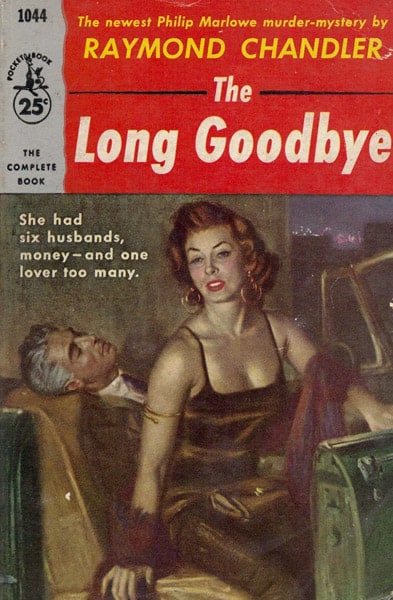

In 1953’s The Long Goodbye, Chandler gives a nod to Los Angeles’ changing demographics by replacing his usual Italian and black gangsters with Mexicans. From tough Mexicans carrying knives to a well-dressed Mexican butler who speaks only Spanish, The Long Goodbye presents the L.A. of the Eisenhower years as an already conquered city. Even Terry Lenox, the center of the book’s investigation, comes back from a long stay in Mexico as something different — not quite white anymore. Marlowe insinuates the he has become more “transplanted Mexican” than “real gringo.”

In uglier language, an earlier Chandler detective, Sam Delaguerra of the short story “Spanish Blood,” upbraids his police chief for assuming that all Mexicans are the same. Delaguerra explains to the chief: “My blood is Spanish, pure Spanish. Not nigger-Mex and not Yaqui-Mex.”

Hammett, whom Chandler cited as the pinnacle of hardboiled writing, also wrote plenty of race-conscious stories. Like the later Chandler, Hammett’s Continental Op stories feature plenty of Asian butlers and immigrant criminals. Both Hammett and Chandler recognized that for their white working-class readers, Asians were economic and demographic competition, especially in California: There were race riots between white and Filipino farm workers in California between 1928 and 1932, and California barred Filipino men from marrying white women in 1933.

In Chandler’s 1934 story, “Smart-Aleck Kill,” a Filipino thug disarms private detective John Dalmas during an intense showdown between cops and robbers. Like most of Chandler’s Filipinos, the thug is a peacock. In his personal life, Chandler’s term for garishness was “as fancy as a Filipino on a Saturday night.” Chandler’s Philip Marlowe novel The High Window gives a general assessment of Asians, specifically of Chinese, as “fairly clean” when at their best. In the 1925 story “Tom, Dick, or Harry,” several Filipino gangsters play a role in a jewel heist in San Francisco. Hammett described them as “shifty.”

For Hammett, California’s Chinese community also provided exotic scenery for his tales. San Francisco’s Chinatown is the location of Hammett’s 1925 short story “Dead Yellow Women,” which shows how alien Chinatown was for the Op and for other white San Franciscans. One of the key characters is Lillian Shan, a supposedly assimilated Chinese-American woman whom the Op finds dressed in traditional Chinese clothes and peddling anti-Japanese propaganda. Back in Chinatown, Shan becomes who she really is. The Op ends the story by swearing off Chinese food for life.

Stories like “Dead Yellow Women” and many other hardboiled short stories have connections to the imperial adventure stories of the Victorian Era. British authors such as Rudyard Kipling and Saki (real name: H.H. Munro) turned their long experiences in places such as India and Burma into horror yarns about how deadly the Asian world can be. Read Saki’s “Sredni Vashtar” and see what British imperialists thought about the practices of their subjects.

During the 1920s, magazines such as Black Mask resurrected this international genre. Alongside Race Williams and Continental Op stories, the magazine published pieces by adventure writers such as John Ayotte and Philip Fisher. In Ayotte’s “White Tents,” a US Army mapping expedition in Hawaii is derailed when a soldier goes mad and kills several of his compatriots in their sleep. The junior officers who hunt him down are convinced he represents something other than human. In Fisher’s “Fungus Isle,” a tropical disease in a far-off Pacific atoll literally turns white skin black. Both tales have the same message: Prolonged exposure to foreign jungles or islands can make whites change mentally or physically.

Likewise, Hollywood films such as Outside the Law and West of Zanzibar — both starring Lon Chaney — are all about the nexus between foreign cultures and crime.

British authors crafting mystery or horror stories about exotic threats always had to bear in mind that most of their readers had never been to the colonies. While plenty of British authors like Dr. Fu Manchu-creator Sax Rohmer and Richard Marsh (author of the Egyptian terror tale The Beetle) did craft popular stories about non-white villains directly threatening white civilization in England, the difference between these stories and the later American private-investigator yarns is that American cities have already been conquered. Cultural chaos does not have to be imported in the form of aliments like Dr. Fu Manchu. The racial consciousness in American detective novels was therefore more thorough and serious, unlike the watered-down version in imperial England.

In the fiction of Chandler, Hammett, and others, the American city has long been occupied by menacing foreigners. The Continental Op, in “Zigzags of Treachery” takes them all in during a single, lonely night in San Francisco: Chinese people move back and forth from Chinatown and Italian workers return to crumbling apartments. In this city, Italian and Chinese immigrants live on the same street, thus deepening the swamp of criminality.

Again, while both British and American writers recognized the danger of multiple civilizations existing within Western cities, Americans have usually seen this as more of a threat. Contrast Conan Doyle’s description of London in A Study in Scarlet as “that great cesspool into which all the loungers and idlers of the Empire are irresistibly drained” with Chandler’s description of Southern California as a marauding miasma that is comparable to murder.

The greatest opponent of polyglot urbanism was another American writer of the interwar years, H.P. Lovecraft. In his story “He,” he envisions a future New York City as a hellish world ruled by “yellow, squint-eyed people . . . . robed horribly in orange and red, and dancing insanely to the pounding of fevered kettle-drums.” Lovecraft and Hammett briefly worked together in 1931 when Hammett included one of Lovecraft’s stories, “The Music of Erich Zann,” in a horror anthology called Creeps By Night.

By the end of the 1920s, American detective fiction had completely separated from its British parent. American private detectives did not embrace the multi-racialism of Sherlock Holmes in “The Adventure of the Yellow Face,” which confirms that marriages between white women and black men can be legitimate so long as the black man is a gentleman and their children are raised as British citizens. Rather, the Continental Op, Marlowe, and other private eyes appreciate their whiteness because of their constant contact with non-white people. Unfortunately for Leftists who sincerely believe that exposure to multiculturalism makes white people more tolerant, the hardboiled stories of the 1920s and 1930s tell us something different: When surrounded by diversity, whites feel a deeper allegiance to their race.

Compared to today’s detective and thriller novels, the hardboiled tales of nearly a hundred years ago are not only more fun to read, but are also blissfully free of political correctness. The Communist Hammett displays more socially conservative impulses than the nominally conservative writer Brad Thor. The moderate liberal Chandler reads like an arch-reactionary when stacked up against Andrew Klavan. Indeed, readers should pour themselves into older American detective novels. They offer a tonic against the rampant Leftism of modern American hardboiled fiction, which is represented by the likes of Dennis Lehane, Gillian Flynn, and Eric Garcia. If you have not yet jumped into the harboiled universe, these are the works that you should pick up today.

Dashiell Hammett, Crime Stories and Other Writings (2001) — A collection of Hammett’s short stories from the 1920s, this book is a great introduction to the earliest days of hardboiled storytelling.

Dashiell Hammett, Red Harvest (1929) — After a crusading reformer and journalist is murdered in the Montana town of Personville, the Continental Op is called in to investigate. He winds up gutting the town by instigating a civil war between a corrupt government and the gangsters they originally hired to squash a labor strike.

James M. Cain, The Postman Always Rings Twice (1934) — This controversial book concerns an amoral drifter named Frank Chambers who meets Cora Smith, the wife of a Greek immigrant who runs a diner. Cora is worried that she has lost her racial identity after marrying a foreigner, and she and Frank plan the murder of her husband.

Mickey Spillane, I, The Jury (1947) — Decades before Dirty Harry was called a “paean to fascism” by Vincent Canby, Mickey Spillane’s popular Mike Hammer novels depicted a depraved New York in need of a fighting cure. Hammer proves here that true justice means killing in the name of a friend.

Mickey Spillane, One Lonely Night (1951) — Hammer stumbles upon an attempt by the American Communist Party and KGB agents to co-opt a political campaign in New York. Hammer uses his all-American fists and his Colt .45 to foil Moscow’s machinations.

Raymond Chandler, The Long Goodbye (1953) — Philip Marlowe tries to rescue fellow alcoholic Terry Lennox. However, Marlowe gets wrapped up in a cross-border case that transforms not only Lennox himself, but also the city of Los Angeles.

Ed McBain, Cop Hater (1956) — McBain is one of the heroes of the police procedural genre. In this book, McBain touches on black criminality, urban degeneracy, and hatred of American police officers.

Jim Thompson, The Getaway (1958) — Jim Thompson was arguably the greatest hardboiled author of them all. This frightening novel is about two criminals who escape to Mexico only to find a fate worse than death.

Ross Macdonald, The Chill (1964) — Macdonald was a noted liberal who fought on behalf of progressive causes. However, his Lew Archer novels often revealed the ugly truth about California in the 1960s, including its unhealthy obsession with youth and its blind support for brain-washing universities.

Robert B. Parker, The Godwulf Manuscript (1973) — Boston’s many college campuses provide the setting for this tough thriller. Working-class detective Spenser is hired as a university professor to find an illuminated manuscript. Along the way, Spenser reveals the ugly truth about the sexual revolution and campus radicalism.