Remembering Sergio Onofre Jarpa

Benjamin Villaroel, American Renaissance, May 10, 2020

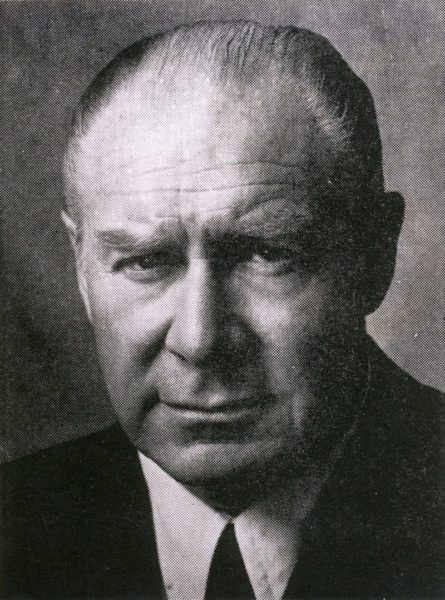

Sergio Onofre Jarpa circa 1965

Last month, Sergio Onofre Jarpa died in Las Condes, one of the ritziest neighborhoods of Santiago. Though hardly mentioned outside of his native Chile, Jarpa’s almost century-long life of political activism is worthy of admiration and emulation for nationalists everywhere. No matter the odds or the set-backs, he always fought valiantly and smartly — electorally when possible, and by other means when necessary — against Marxism, for national greatness, and for a right-wing that was bigger than free market “economism.” Chile is better for it.

Born in 1920 in the small town of Rengo, as a young man, he became involved in the “third position” politics that were gaining ground around the world. In the 1930s, he was a member of the Popular Liberation Alliance and the Popular Socialist Vanguard, both of which worked hard to bring Carlos Ibáñez del Campo, the Chilean equivalent to Juan Perón, back to power. In 1938, a coup for that purpose failed, and led, in part, to Pedro Aguirre Cerda, an FDR-like figure, winning the next presidential election. Whether Jarpa had a role in this failed coup has never been confirmed, but admirers who believe he was involved see this as the first of many times Jarpa risked everything for a cause, lost, but survived to fight the next battle.

As Chile’s various nationalist-populist parties began to crumble because of ties to the failed 1938 coup or their associations with National Socialism, Jarpa joined and then directed the youth wing of the Agrarian Labor Party, which tried to unify scattered nationalist activists and shed negative associations.

The Agrarian Labor Party’s emblem.

Jarpa was deeply involved in electoral politics, but not blind to alternative avenues to power. By 1948, the leftist Radical Party had been in power for 10 years and showed no signs of weakening. He plotted with high-ranking military officials and nationalist activists to overthrow President González Videla and reinstate Carlos Ibáñez del Campo. This plan was eventually foiled, and the President’s term went uninterrupted. Jarpa was definitely involved in the 1948 plot, but slipped through the legal system and avoided execution, exile, or even prison.

President González Videla finished his term, but became less popular each year. Ibáñez del Campo, by then a Senator, ran for president in the next election in 1952, and won with 46.79 percent of the vote. After nearly two decades of activism, Jarpa got his man in office. This crushed both the free-marketeer candidate Arturo Matte Larraín (who won 27.81 percent of the vote), and the leftist, Pedro Enrique Alfonso Barrios (19.95 percent).

President Carlos Ibáñez del Campo circa 1952

President Ibáñez del Campo served a full term until 1958. Though his administration failed to deal with Chile’s chronic inflation and came to a close with little popular approval, his 1952 electoral victory was critical to breaking the Radical Party’s dominance of national politics, and also proved that a national populist right could take the place of the historic aristocratic right. Unfortunately, like so many caudillos, when he died in 1960, he left no organization or political heir. Socialism was on the rise around the world, and Fidel Castro had brought it to Latin America. In Chile, a new center-left party, the Christian Democrats, was on the rise, attracting many members of the historically conservative elite and even more of the growing college-educated middle class. By the 1964 elections, the right was in such disarray that there was no conservative presidential candidate. Once again in the wilderness, Jarpa co-founded another dissident right-wing organization, the National Action Party, in the hope of creating a political group to fight leftism more effectively than had the traditional parties of the right.

The country lurched left in the sixties. In 1966, Jarpa set up a meeting with the leaders of every faction of the Chilean right. At the end of the meeting, and with an eye on the 1970 presidential election, all nationalist and conservative parties were dissolved and one new united party was formed: the National Party. Jarpa knew that if he did not make common cause with former rivals, Chile could become another Cuba. The Left did its best to stop this sudden unification of the right. In one dramatic example, President Eduardo Frei imprisoned the entire party’s Steering Committee, including Jarpa, on trumped up charges of threatening national security. They were released only after taking their case to the Supreme Court.

The plan of victory through a united right very nearly worked. In 1970, the National Party candidate, Jorge Alessandri, lost to socialist Salvador Allende by 1.34 percent of the vote. Though Chile had moved sharply left between 1964 and 1970, the next 1,000 days were a rapid spiral into Marxist dystopia. Jarpa, though in his 50s, was still tireless. In 1971, he was elected alderman of Santiago, ensuring that the nation’s capital city would oppose the federal government, and he helped found Tribuna, one of the many dissenting newspapers launched during the Allende years. In 1972, Jarpa was elected to the Senate and helped found the Democratic Confederation, a coalition of every major party against the Socialist and Communist Parties. Once again, Jarpa was willing to work with former rivals, in this case even with the Christian Democrat ex-president Eduardo Frei who had sent him to prison. He was also a regular and ferocious critic of the Marxist government on national TV:

On September 11, 1973, a military coup overthrew Salvador Allende and replaced him with General Augusto Pinochet. Again, Jarpa’s level of involvement with this coup is a secret that went with him to the grave. Regardless, he was a friend of the new government and served it well. In its early years, he held a number of ambassadorships, first to the United Nations, then to Colombia, and finally to Argentina, where he played a key role in de-escalating the “Beagle Channel Dispute” that could have led to a catastrophic war with Argentina.

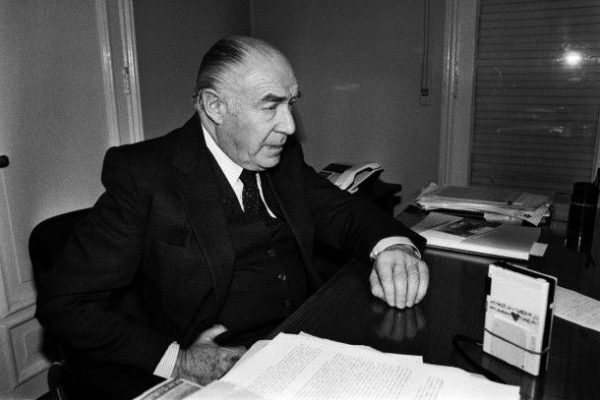

Minister of the Interior Sergio Onofre Jarpa circa 1983.

The economic crash of 1982 led to serious discontent that led to a cabinet reshuffle in 1983. Jarpa was named Minister of the Interior — the second most important post in Chile’s executive — and demanded that the government put people over pesos and scale back the harshest austerity measures imposed by Pinochet’s neoliberal reforms. Modest government intervention to help the middle and lower classes, and easing the principle of “small government no matter the results” stabilized the country and won grudging respect from the proletariat for the military government.

As the 1980s came to a close and a transition to democracy seemed inevitable, Jarpa recognized that a cult of personality around Pinochet and slavish devotion to “Chicago school” economics would not help the right hold on to power. The military government disagreed, and launched the Independent Democratic Union (UDI) in 1983, with a platform mainly about the primacy of capitalism and the near godliness of Pinochet. When a another right-wing party, National Renewal (RN), was founded in 1987, Jarpa saw it as a less ideological and less baggage-laden way to prevent leftist hegemony in any post-Pinochet era. After a controversial internal power struggle, Jarpa became the President of RN and in three years turned it into the party it is today.

A National Renewal event in 1988, with Sergio Onofre Jarpa (center) presiding as its President.

Jarpa’s instincts were correct. Despite its bluster and impressive number of registrants, UDI has never reached the heights so many leftists feared it would in the late ’80s. In 1989, Jarpa was set to run for President under the RN banner, but out of deference to unity and the military government, bowed out to not siphon off votes from the UDI candidate, free market fundamentalist Hernán Büchi, who went on to win only 29.4 percent of the vote. Since then, the UDI has gone on to lose three more presidential elections, the most recent of which (in 2013) by 24.34 percent of the vote. RN, meanwhile, has won two of its three tries for the Presidency, most recently (in 2017) with Sebastián Piñera, who may well undo the wave of immigration the prior Socialist administration introduced.

Jarpa himself served in the Chilean Senate as a member of RN from 1990 until 1994. He then retired, afraid that like many other important members of the military regime, he could be tried and sent to prison. In 1999, the same Spanish Judge who attempted to have Pinochet brought to an international trial for crimes against humanity issued an extradition request against Jarpa on the same charges. Again, Jarpa slipped through the net.

Sergio Onofre Jarpa circa 2009

The most important Chilean nationalist of the 20th Century died of COVID-19 on April 19, 2020. My great-grandfather considered him a hero, and the last time I lived in Santiago, I tried hard to track him down, but to no avail. Chile has lost a true patriot, and I am sad I wasn’t there to attend his funeral. His accomplishments live on in innumerable ways — as even his detractors will admit, Chile would be a very different place today if he had not lived. He should be a model to nationalists everywhere. Sergio Onofre Jarpa was tireless, willing to take enormous risks, forge important alliances, compromise strategically, stand his ground when necessary, and persevere even when victory seemed impossible. May we all follow his example.

Bibliography

Patricia Arancibia Clavel, Claudia Arancibia Floody, and Isabel de la Maza Cave, Jarpa: confesiones políticas. Santiago: La Tercera, Mondadori, 2002.

Sofía Correa Sutil, Con las riendas del poder. La derecha chilena en el siglo XX. Santiago: Sudamericana, 2005.

Cristián Garay, El Partido Agrario Laborista. 1945-1958. Santiago: Andrés Bello, 1990.

Tomás Moulian, Chile actual: anatomía de un mito. Santiago: LOM Ediciones, 1997.

Verónica Valdivia Ortiz de Zárate, Nacionales y gremialistas. El parto de la nueva derecha política chilena. Santiago: LOM Ediciones, Santiago, 2008.