Waukesha Murder Trial — Opening Arguments

Anastasia Katz, American Renaissance, October 7, 2022

The trial of Darrell Brooks, Jr. began on Thursday. He is the black man who drove his SUV through the Waukesha Christmas parade on November 21, 2021, wounding more than 60 white people and killing six.

Mr. Brooks would have been in jail that day if his bail for prior offences been not been reduced. In July 2020, he was accused of firing a gun at his nephew and another person, and he was to go to trial in February 2021. His bail was set at $7,500, but the DA’s office was struggling with a backlog and couldn’t make that date, so the bond was reduced $500 and he was released. He then tried to run over his girlfriend with the same car he used at the parade and was charged with endangerment, but then got out on $1,000 bond, which his mother posted. He has a 50-page rap sheet of crimes committed in Wisconsin, Georgia, and Nevada, including domestic violence, child sex, firearms, drugs, and battery.

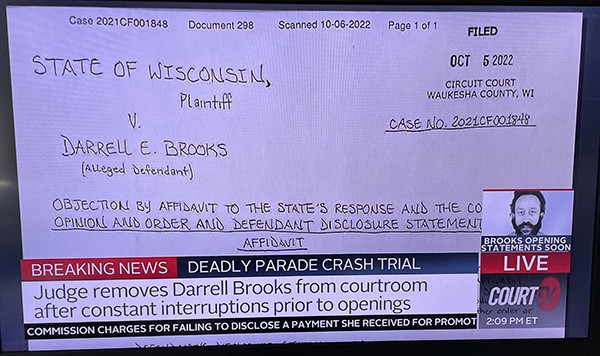

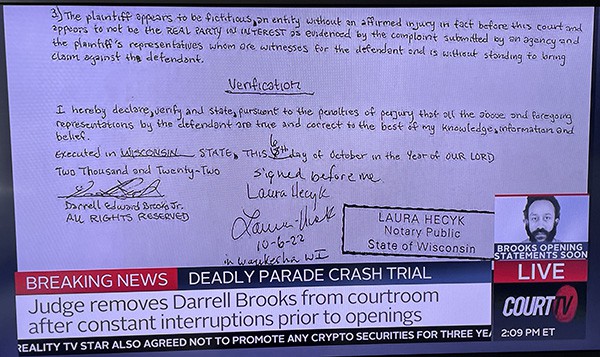

This trial is unusual because Mr. Brooks is defending himself. During pretrial motions, his behavior was erratic, but prosecutor Susan Opper argued that he was competent to defend himself. As evidence, she produced a written filing Mr. Brooks had submitted, which she said was “immaculate” in spelling and punctuation. She told the judge, “He understands the issues; he understands the defense that he wants to pursue. We are 100 percent convinced that these [disruptive] actions of Mr. Brooks are deliberate and intentional . . . . that he is attempting to derail these proceedings and avoid the inevitable. . . . We have zero concern as to the mental competency of Darrell Brooks to proceed.”

Mr. Brooks showed up in court wearing his jail-issued orange clothing. The court has given him a suit, and Judge Jennifer Dorow, a white woman, offered to let him go change, noting that he had appeared in court previously wearing a suit and tie. She reminded him that the orange clothing makes it clear he is in custody, and the judge explained that the court had taken measures to shield the jury from knowing this. His hands are not shackled, but his ankles, which were out of sight, are. She said it was his choice, but she preferred that he change. Mr. Brooks asked, “At this point, who doesn’t know I’m in custody?”

The judge said that she had done trials in which jurors said that they did not know the defendant was in custody until the trial was over. She also said that it would lend dignity to the proceedings if he wore the suit.

Mr. Brooks said the news reports were all saying he was in custody, and which jail he was in, so everyone would know. When the judge asked him directly if he would go back and change, he answered, “I think that’s a well-known fact . . . . Where I am, which jail I’m housed in, and that I’m in custody.”

He refused to wear the suit, and the judge told him he could change at any time. She explained his rights thoroughly, so he would not have a chance to appeal. Mr. Brooks stayed in his jailhouse orange.

Mr. Brooks interrupted Judge Dorow several times as she gave jury instructions, so she said he would be removed. The jury was excused. Before being escorted out, he declared that he was under duress because he was shackled, and he asked for a motion to dismiss. A motion to dismiss needs proper paperwork and was completely out of place.

Mr. Brooks was brought to another nearby courtroom where he could watch remotely. The people in the main court room could also see him. He could speak, but the judge had the option of muting him. In the secondary courtroom, Mr. Brooks took off his shirt and stood with his back to the camera. He also held up a blue sign that said, “Objection.”

Jury instruction, which typically includes the judge reading all charges, was long because there are 77 charges, such as “recklessly endangering the safety” of persons and “showing utter disregard for human life, while using a dangerous weapon.” The charges include bail jumping. The courtroom was filled with victims and families of victims, and some cried when their names were read.

After jury instruction, Mr. Brooks asked to come back to the main courtroom and was escorted in. The judge told him she would remove him again if he was disruptive. There was a tedious exchange when the judge asked Mr. Brooks to sit down. He argued that it was his right to stand, and kept interrupting her. She let him stand. Judge Dorow could appoint standby counsel to offer advice, but she did not do so.

Mr. Brooks claimed that he did “not understand the nature and cause” of his charges. He stayed in the main courtroom when the jurors were brought back after the lunch break and remained standing. He would not stop talking, and the judge told him several times, in front of the jury, to be quiet. There was another rough patch when Mr. Brooks handed a note to a deputy asking for his filings to be addressed. The judge refused.

Mr. Brooks then called for a “motion for a finding of fact.” The judge denied the request and added, “If you think that I’ve made an error, you can raise that on appeal.” “I know you’re making an error, Your Honor,” said Mr. Brooks.

Mr. Brooks claims he is not being allowed freedom of speech in the court room. The judge explained that there are written rules about court decorum. “While you have a right to present a defense, you do not have a right to disrupt the proceedings.” “I’m referring to the First Amendment, which clearly says that I have the right to freedom of speech, and to be heard in the courtroom,” he replied, “Are you not going to honor my constitutional right, Your Honor?” This went on for some time, until Judge Dorow ruled that Mr. Brooks forfeited his right to present in the court room and had him removed.

Mr. Brooks later claimed that one of the jurors had been present at his initial pretrial appearance. “She flipped me off coming into my initial appearance and coming out. I know it’s her.” Judge Dorow said that during jury selection, he had the right to strike the juror for cause and he did not do that, but she said she would later ask the juror if she had been at the defendant’s initial appearance.

The judge told Mr. Brooks he could come back into the main court room to hear the prosecutor’s opening statement, but he got into a long argument in which he said if there was something he didn’t understand, he would ask questions. She kept him out.

Waukesha County Assistant District Attorney Zachary Witchow gave a brief and dramatic opening statement. He began by describing the idyllic Christmas parade festivities, in which children run in the street to grab candy thrown by folks marching down Main Street. He said that there was a sense of joy in the air. “Brooks killed that joy.”

Mr. Witchow promised evidence will show that Brooks committed crimes at the parade because he was fleeing from another crime, one in which he laid hands on a woman.

He said Mr. Brooks careened down Main Street, “hands glued to the steering wheel, eyes fixed on the road in front of him, and with silent rage on his face, he hit the gas of his red Ford Escape, and used it as a battering ram, over and over again, striking men, women, and kids.” He said Sergeant Wanner, who was in charge of police at the parade, will come to court and use a map to explain everything that happened. Mr. Witchow showed the map to the jury and began a brief explanation.

Then he told the jury that they would hear about the violent argument Darrell Brooks had with his ex-girlfriend, Erika Patterson, who will also testify. He told the jury she will say that the day of the parade, the defendant argued with her and punched her in the eye. He showed a photo of Miss Patterson, a black woman, with a swollen eye. He said the police came, and Mr. Brooks got in his car to escape and drove towards the parade route.

The prosecutor told the jury that Mr. Brooks will probably say he “didn’t mean” to kill anyone, and he asked the jury to consider, as the evidence is presented, whether the defendant was aware that his conduct was practically certain to cause the death.

Mr. Witchow talked about people in the parade. The Extreme Dance Team included all ages, from tots in strollers to teenage dancers. Fifteen people with this group were either struck or close to being struck, as were those watching the parade. Girls on the dance team “suffered catastrophic injuries.” Mr. Witchow said “The Dancing Grannies” was at “the deadliest point in this parade. Seven people in this group were struck. Four of them died.”

There will be speed analysis from the Wisconsin State Patrol, and Mr. Witchow said Darrell Brooks was going 32 mph when he plowed through the Dancing Grannies. As the prosecutor spoke about the Dancing Grannies, Mr. Brooks, in his secluded room, pressed his hands together as if in prayer and looked down.

Mr. Witchow said the jury would be watching many videos. He thanked the jury for their service, adding that he would be mindful of their time, but they have “a lot to get through.”

Judge Dorow asked Mr. Brooks if he would be making an opening statement. “I will be deferring at this time, Your Honor,” Mr. Brooks said, “I will need a little more adequate time to go over the points that I need to make.”

The jury was sent out after the opening, and Mr. Brooks and the judge had a long exchange about how to make objections that showed how deeply he is in over his head. He also could not convince the judge that he would behave, so she left him in isolataion.

The jury returned and Mr. Witchow called his first witness, Sergeant David Wanner of the Waukesha Police Department. He said police put signs and barricades along the parade route and they had “significant manpower” because of the large crowd.

Sgt. Wanner showed the jury a map of the parade area. Mr. Brooks said “Objection” many times, but Judge Dorow overruled every time.

At one point, Sgt. Wanner saw a red SUV coming towards him at about 40 mph in a 25 mph zone. He waved his arms over his head to catch the attention of the driver. Mr. Witchow asked if the sergeant had been in uniform, and he said yes. The car kept going and entered the parade route.

“As I got to my squad car,” Sergeant Wanner said, “I was bombarded with the most terrible, uh. . . ” He drew in a breath, sighed, and was speechless for a few moments. He finally managed to say, “The most terrible thing you ever heard.” What he heard was other officers making radio calls for help.

Darrell Brooks started cross-examination with an odd question. “If you weren’t here testifying, would you have been on duty today?” Sgt. Wanner said that it was an “off day” and he would not have been at work.

Next Mr. Brooks asked, “Did you feel that the testimony you were giving today required you to be in uniform?” The state objected on relevance, and the judge sustained. The prosecution objected to a string of questions on vagueness and irrelevance, and the judge sustained them all.

The second witness was Kori Runkel, a young white woman, who was a friend of Erika Patterson, Darrell Brook’s ex-girlfriend and the mother of his child. Miss Runkel said she met Miss Patterson shortly before the Christmas parade at a women’s shelter, where they bunked together. On November 21, the two were at a park by a river, and Miss Runkel overheard Miss Patterson talking on the phone with Mr. Brooks. After the two women had split up, Miss Runkel called her to say Darrell Brooks was beating her up and was following her. Miss Runkel went to help, and said Mr. Brooks had been “swerving at” his ex-girlfriend with his car, and yelling at her to get back in the car. Miss Patterson tried to get back in, but Miss Runkel pulled her back. The state played a surveillance video, which Miss Runkel said was a fair depiction of what happened.

Kori Runkel

Miss Runkel’s testimony was hard to follow. She said she saw Miss Patterson get “ran over” and then get in the car, and she (Miss Runkel) “chested up” to Mr. Brooks. There was a loud argument. Darrell Brooks got back into his car, and as he was leaving, told Miss Patterson that “he was going to find her and he was going to kill her.” A nearby security guard called the police, and Miss Runkel told an officer what happened.

Mr. Brooks was asked to remove his surgical mask so Miss Runkel could identify him, and at first, he refused. After he unmasked, she identified him..

The state showed Miss Runkel a photo of Miss Patterson with a swollen eye; Miss Runkel testified that the eye had not been swollen when the women had been together earlier.

On cross examination, Mr. Brooks clumsily gave Miss Runkel the opportunity to tell the jury — several times — that he had threatened to kill Miss Patterson. He tried to impeach Miss Runkel by saying that he had her statement to the police in front of him, and she did not tell the police that he had made any threats. Mr. Brooks then made trouble for himself by reading aloud Miss Runkel’s statement, in which she said she heard Mr. Brooks tell Erika Patterson that he was “going to smash her face in and kill her.”

On redirect, the state drew further testimony that Miss Runkel told the police that as Mr. Brooks got into his car, she heard him say, “Fuck you, fucking bitches, you’re dead!”

Mr. Brooks did show during his bumbling cross-examination that he has thought about his defense. He asked Miss Runkel what she was doing when she was “hanging out” in the park, and got her to admit she had been drinking vodka and was tipsy. He also managed to get her to admit that Miss Runkel had never met Mr. Brooks before, which could cast some doubt on the accuracy of her identification.

Mr. Books is grasping at straws, but with all of the video evidence against him, a real defense lawyer would also be grasping at straws. The trial continues today.