A Drumbeat of Multiple Shootings, but America Isn’t Listening

Sharon LaFraniere, Daniela Porat, and Agustin Armendariz, New York Times, May 22, 2016

{snip}

The Elks Lodge episode [described above] was one of at least 358 armed encounters nationwide last year–nearly one a day, on average–in which four or more people were killed or wounded, including attackers. The toll: 462 dead and 1,330 injured, sometimes for life, typically in bursts of gunfire lasting but seconds.

{snip}

They chronicle how easily lives are shattered when a firearm is readily available — in a waistband, a glove compartment, a mailbox or garbage can that serves as a gang’s gun locker.

{snip}

The shootings took place everywhere, but mostly outdoors: at neighborhood barbecues, family reunions, music festivals, basketball tournaments, movie theaters, housing project courtyards, Sweet 16 parties, public parks. Where motives could be gleaned, roughly half involved or suggested crime or gang activity. Arguments that spun out of control accounted for most other shootings, followed by acts of domestic violence.

{snip}

Most of the shootings occurred in economically downtrodden neighborhoods. These shootings, by and large, are not a middle-class phenomenon.

The divide is racial as well. Among the cases examined by The Times were 39 domestic violence shootings, and they largely involved white attackers and victims. So did many of the high-profile massacres, including a wild shootout between Texas biker gangs that left nine people dead and 18 wounded.

Over all, though, nearly three-fourths of victims and suspected assailants whose race could be identified were black. Some experts suggest that helps explain why the drumbeat of dead and wounded does not inspire more outrage.

“Clearly, if it’s black-on-black, we don’t get the same attention because most people don’t identify with that. Most Americans are white,” said James Alan Fox, a professor of criminology at Northeastern University in Boston. “People think, ‘That’s not my world. That’s not going to happen to me.’ ”

Michael Nutter, a former Philadelphia mayor, who is black, said that society would not be so complacent if whites were dying from gun violence at the same rate as blacks.

“The general view is it’s one bad black guy who has shot another bad black guy,” he said. “And so, one less person to worry about.”

Minor Dust-Ups, Answered With Bullets

Droves of experts study high-profile massacres by so-called lone-wolf assailants, usually driven by mental disorders, at schools, workplaces and other public spaces. Academics regularly crunch data on single homicides and assaults. But the near-daily shootings that wound or kill several victims — a relatively small subset of the shootings that kill nearly 11,000 people and wound roughly 60,000 more each year — are uncharted territory for researchers, said Richard B. Rosenfeld, a professor of criminology at the University of Missouri-St. Louis.

{snip}

Counting assailants among casualties increased the total number of cases by fewer than three dozen, most of them domestic violence shootings that ended in suicide. Hispanics were not separately identified, because police reports do not systematically identify victims and suspects by ethnicity, only by race.

{snop}

39 Domestic Violence Cases

145 Dead

40 Injured

White attackers: 63%

White victims: 64%

{snip}

Another third of the 358 cases — and the most common in cities with more than 250,000 residents — were either gang-related or were drive-by shootings typical of gangs.

But the police and prosecutors say many of those were not directly linked to criminal activity, such as a dispute over a drug deal. More often, a minor dust-up — a boast, an insult, a decision to play basketball on another gang’s favorite court — was taken as a sign of disrespect and answered with a bullet, said Andrew V. Papachristos, a Yale University professor who studies gang behavior.

Typical Victim: Male 18-30

Race known: 67%

Black: 73%

Sex known: 80%

Male: 72%

Average age: 27

Includes Hispanics among both races.

Over all, two-thirds of shootings took place outdoors, endangering innocent people. More than 100 bystanders, from toddlers to grandparents, were injured or killed.

{snip}

In Rochester, multiple-victim shootings accounted for fewer than 15 percent of victims in 2006; so far this year, they make up 38 percent. Police Chief Michael Ciminelli said that he suspected that social media was playing a role by simultaneously catalyzing minor disputes into deadly standoffs and drawing more people into them.

{snip}

Street violence is self-perpetuating that way: Shootings beget shootings that beget more gunmen. Professor Papachristos, the gang expert, said the more violent the neighborhood, the more teenagers and young men seek safety in numbers.

“The No. 1 reason people join gangs is for protection,” he said. “The perverse irony is they are then more at risk.”

Ali-Rashid Abdullah, 67 and broad-shouldered with a neatly trimmed gray beard, is an ex-convict turned outreach worker for Cincinnati’s Human Relations Commission.

{snip}

“White folks don’t want to say it because it’s politically incorrect, and black folks don’t know how to deal with it because it is their children pulling the trigger as well as being shot,” said Mr. Abdullah, who is black.

{snip}

“These are our children killing our children, slaughtering our children, robbing our children. It’s our responsibility first.”

African-Americans make up 44 percent of Cincinnati’s nearly 300,000 residents. But last year they accounted for 91 percent of shooting victims, and very likely the same share of suspects arrested in shootings, according to the city’s assistant police chief, Lt. Col. Paul Neudigate.

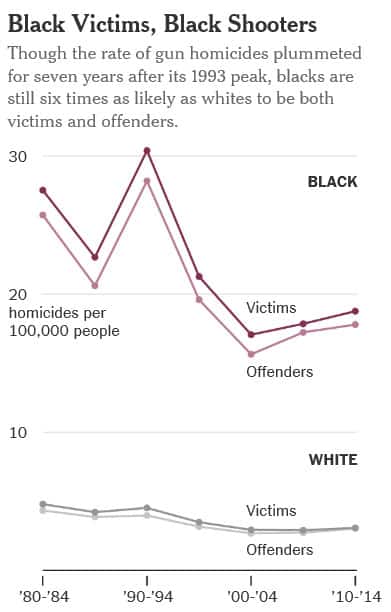

Nationally, reliable racial breakdowns exist only for victims and offenders in gun homicides, not assaults, but those show a huge disparity.

The gun homicide rate peaked in 1993, in tandem with a nationwide crack epidemic, and then plummeted over the next seven years. But blacks still die from gun attacks at six to 10 times the rate of whites, depending on whether the data is drawn from medical sources or the police. F.B.I. statistics show that African-Americans, who constitute about 13 percent of the population, make up about half of both gun homicide victims and their known or suspected attackers.

{snip}

Some researchers say the single strongest predictor of gun homicide rates is the proportion of an area’s population that is black. But race, they say, is merely a proxy for poverty, joblessness and other socio-economic disadvantages that help breed violence.

{snip}

After a white University of Cincinnati police officer fatally shot an unarmed black driver in July, street protests erupted here, Mr. Abdullah noted. But “when we kill each other,” he said, “it seems an acceptable way of life.”

{snip}

Nationally, nearly half of last year’s shootings with four or more casualties ended in the same way: no arrest; often, not even a suspect. At least 160 assailants, responsible for 102 murders and 635 gun injuries, were still on the streets at year’s end.

A case was more likely to be solved if one or more victims died — the situation in about half the cases. But even some double, triple and quadruple murders continue to stump investigators.

The national clearance rate for homicides has fallen from nearly three in four in 1980 to fewer than two in three today. That is partly because public attention has driven down the share of domestic violence killings, which are routinely solved, Professor Rosenfeld said.

Much of what remains are killings involving gangs, drugs and witnesses with criminal backgrounds who are wary of talking to the police. “You are left with a larger percentage of homicides that are more difficult for police to clear,” he said.

A shift in law enforcement from solving crimes to preventing them has also contributed, as has rising distrust of the police in some cities, said Charles F. Wellford, emeritus professor of criminology at the University of Maryland. Still, he said, some law enforcement agencies are much worse at closing murder cases than others. Some of those same departments are worse at closing shootings with four or more casualties, too.

In Baltimore, the police have not solved any of 11 shootings last year. New Orleans made arrests in only one of eight cases; Chicago, two of 16.

Cincinnati was more typical, solving two of its five cases, at least in part.

{snip}

Mr. Abdullah, the anti-violence worker, talks to some of the victims and witnesses who will not give information to the police. “They are scared,” he said. “We have had cases where people found out who talked and that person wound up dead. ‘So if the police cannot protect me, why would I jeopardize my life and my family?’ ”

“It’s so much bigger than the idea of ‘no snitching,’ ” he said.

{snip}