German Efforts to Improve Birthrate a Failure

Spiegel, December 18, 2012

Each year, the German government spends billions of euros in an effort to stop the country’s ticking demographic time bomb. By 2050, it is estimated that only 70 million people will be living in the country, down from today’s roughly 82 million. Without a major change in the birthrate or a mass influx of up to 24 million new immigrants, the population could soon begin shrinking, according to United Nations forecasts.

To make having children more attractive, in recent years Berlin has increased monthly government subsidies paid to families with children, benefits for parents who stay home to care for newborns, work leave payments for new fathers and an expansion of national day care services. Despite these efforts, however, the German birthrate has remained at a constant average of 1.4 children per woman for around 40 years.

On Monday, the German Federal Institute for Population Research issued a report looking into the reasons behind the failure to increase the country’s birthrate. The results are sobering. For many Germans, establishing a family has taken a backseat to a career, hobbies and friends. The report concludes that “children no longer represent a central aspect of life for all Germans.”

The reasons for this development are myriad. For one, societal views on parenting have changed considerably. Fifty years ago, a person in Germany was first considered to be a grown up after they had established a career, gotten married and had children. But today society doesn’t provide the same level of recognition for having children. Statistics show that few believe their position in society will be improved by having offspring. Many people even fear that having more than two or three children could actually put them at a real disadvantage.

Career and Family Compete

The study found that many Germans believe reconciling career and family is problematic. Particularly among mothers, concerns about finding the balance between time spent with children and at the workplace are considerable. Those who find this balancing act too challenging are ultimately forced to decide between child and career. In addition, many women, particularly in the western German states, still ascribe to outmoded societal norms. The idea still persists that women are somehow neglecting their children if they hand them over to day care within their first three years of life. There’s even a disparaging term in German to describe these women: “Rabenmütter,” or “raven mothers,” who push their children out of the nest too soon. Particularly among the more highly qualified, many simply decide not to have children.

Somewhat surprisingly, the report also shows that men in Germany today are not considered to be adequate replacements for mothers when it comes to being the primary caregiver for young children. As a society, Germany has considerably less faith in its men than neighboring countries that include Belgium and France. In both of those countries, there is much greater acceptance for working mothers than in Germany.

The degree of these difficulties is also reflected in overall attitudes about raising children. According to the study, children are no longer viewed as an obvious source of satisfaction and happiness. Only 45 percent of childless Germans between the ages of 18 and 50 believe that they would have happier lives or that they would have greater satisfaction if they were to have children in the coming three years.

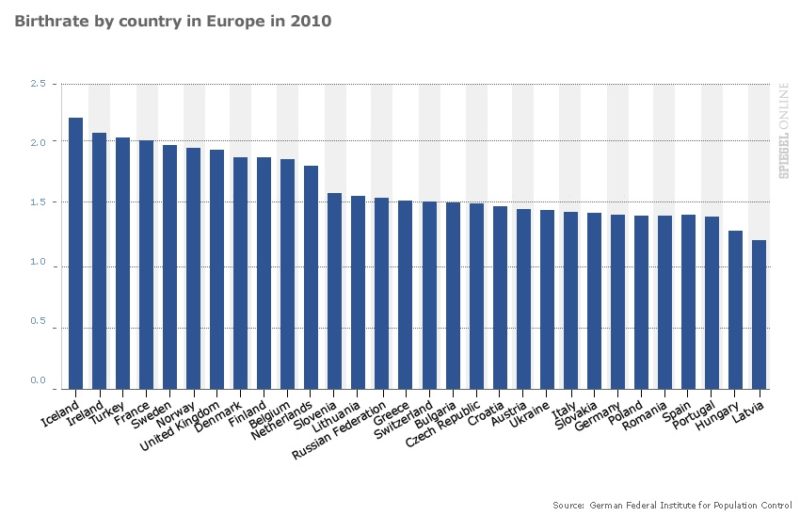

The study marks the first time that the Federal Institute for Population Research, a division of the Interior Ministry, has compared German views on having children with those elsewhere in Europe. Only 10 countries in Europe have lower birthrates than Germany, the report states. In Germany, the average rate is 1.39. Latvia, with 1.17, has the lowest birthrate in Europe, while Iceland leads the list with an average of 2.2 children.

Although some European countries have seen growth again in their birthrates in recent years, that trend hasn’t crossed over into Germany. Indeed, in a global comparison, Germany has the highest percentage of women who do not have children over the long term. Around one-fourth of women born between 1964 and 1968 have deliberately chosen not to have children, the report found.

Indeed, the desire to have children doesn’t appear to be as widespread as it is in other European countries. There are only six other countries in Europe where the majority of those polled say they wanted no children or fewer than two children.

Policies Encourage Mothers to Stay Home

A study released on Monday by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) offered Germany a similarly poor report card on gender equality. Despite the fact that young German women are better educated than their male counterparts, their prospects for success on the labor market aren’t as good, it found. The study also criticized numerous aspects of Germany’s family policies, which it said contributed to a serious gender gap.

The report warned that the controversial new Betreuungsgeld, or care allowance for staying home with children aged 13 to 26 months, encourages mothers with young children not to work, and thus exacerbates persisting gender inequalities in the country. The organization also criticized the system of joint income tax filing for married couples in Germany, called Ehegatten-Splitting, for being the only taxation system in the OECD “which does not provide both parents in couple families with broadly similar financial incentives to work when children are of school age.” The organization added that Germany needs to boost efforts to provide quality affordable child care.

The report found that 27 percent of women in Germany between the ages of 25 and 34 have completed their tertiary education at a university or other institution. Only 25 percent of men in the same age range had accomplished the same level of education. And although more women in many countries work today than they did 20 years ago, in Germany, Austria and Switzerland a disproportionate number are working part-time. “That has a negative impact on their income and on their career,” the report found. It also showed that at median earnings, the gender pay gap is on average 22 percent, the third-highest rate in the OECD. For the self-employed, that figure is a staggering 63 percent less.

All this, of course, has implications for women when they retire. According to the OECD report, the average pension payment to women is about half of what is paid to men in Germany, making the “pension gap” the largest among the countries that are members of the organization. The report blamed “shorter work histories, fewer working hours and lower earning” for the disparity.