Whitewashing Jack Johnson

Addison N. Sheffield, American Renaissance, June 2009

Senator John McCain (R-AZ) and Representative Peter King (R-NY) have joined documentary filmmaker Ken Burns, a noted apologist for blacks, in a bid to get a posthumous pardon for the first black heavyweight boxing champion, Jack Johnson (1878-1946). Earlier efforts to arrange a pardon for Johnson’s conviction for violating the Mann Act have been unsuccessful, with one bill stalling in Congress just last year. However, Johnson is a hero to many blacks and to the most truckling sort of whites, so there is a good chance President Obama will grant a pardon. During his lifetime many Americans considered his a career a standing insult to whites — which makes him a particularly appealing candidate for amnesty.

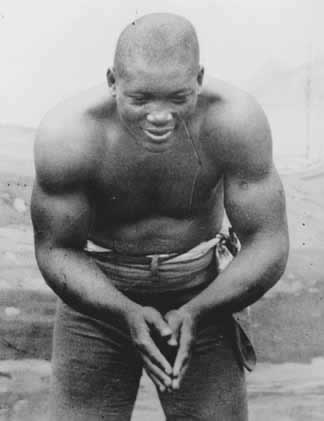

Heavyweight champion Jack Johnson

Jack Johnson, who was born in Galveston, Texas, but later moved to Chicago, was the original loutish celebrity athlete. In the early 20th century, when white supremacy was still the norm, he taunted his opponents both in and out of the ring, and boasted about his endless fornications with white women. He was the first black man ever to be allowed to fight for the prestigious heavyweight championship, which he won from Tommy Burns in 1908 in Sydney, Australia. In a particularly cruel fight, he not only insulted his opponent, but held him up several times when he was about to go down so he could punish him some more.

Johnson’s claim to the title was disputed, however, because Burns had been declared heavyweight champion following the voluntary retirement of the undefeated champion, James Jefferies. Many people considered Burns something of a fake because he had never fought Jeffries.

Johnson in his prime

The call went out for a “Great White Hope” to regain the title for the white race, and in 1910, former champion Jeffries came out of retirement for what was widely billed as “the fight of the century.” Jeffries said he accepted the challenge “for the sole purpose of proving that a white man is better than a Negro,” but he had not fought in six years and had to lose 100 pounds to get back to fighting weight. After Jeffries hit the canvas twice in the 15th round and conceded the match, there were race riots in more than 50 cities, in which 23 blacks and two whites were killed. Many riots started when angry whites attacked spontaneous public celebrations by blacks. Some whites were so upset by the outcome of the fight that in 1912 they persuaded Congress to ban the interstate distribution of boxing films that showed Johnson beating a series of white opponents. Southern detractors threatened to lynch the champion if he ever returned to Dixie.

This, then, was the background to Johnson’s prosecution under the Mann Act. The act, passed in 1910, got its name from its chief sponsor, Congressman James R. Mann (R-IL). The statute authorized federal prosecution of anyone who transported a woman across state lines “for immoral purposes.” Congress claimed that its authority to regulate interstate commerce could be used to stop the white slave trade.

The act was part of a series of religious and Progressive Era reforms aimed at civilizing American society, and the city of Chicago took part enthusiastically in this effort. Johnson, however, continued to flaunt his insatiable sexual appetite, especially in the aftermath of his victory in “the fight of the century.”

In an era when anti-miscegenation laws were still on the books in many states and firmly enforced in the South, Johnson scandalized the country by marrying not one, but two white women in rapid succession (all three of his wives were white). His first marriage was to New York socialite Etta Terry Duryea, who had divorced her first husband, an automobile manufacturer, before taking up with the boxer. The newlyweds’ turbulent relationship ended in less than two years when Etta committed suicide by shooting herself. Johnson had probably been beating her and she was said to be depressed by his infidelities.

By then, Johnson had already taken up with a 24-year-old white prostitute named Lucille Cameron, whom federal authorities hoped to recruit to testify against Johnson in the first-ever prosecution under the Mann Act. She refused to testify and Johnson married her — just three months after his first wife shot herself.

Johnson, who was paid $225,000 for his fight with Jeffries, traveled the country with his new bride and another prostitute, Belle Schreiber, who had left a brothel to join the entourage. This tour spurred federal prosecutors back into action, and they charged Johnson with transporting Schreiber from Pittsburgh to Chicago for immoral purposes. From the start there were claims the charges were trumped up and racially motivated, but a jury found Johnson guilty on seven separate counts, and he got the maximum sentence of a year and a day. Johnson fled the United States for Canada, disguised as a member of a barnstorming Negro baseball team, and later went to Paris. The outbreak of the First World War broke up the party and Johnson left France as a man without a country.

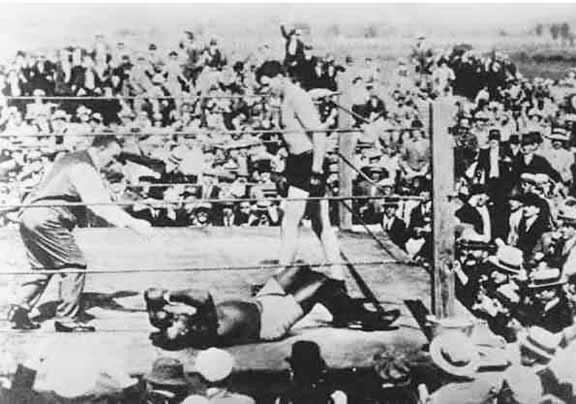

After traveling to various places, Johnson, who had by now run through all his money, agreed to defend his title against a challenger from Kansas, Jess Willard. The championship fight between Johnson and “the Pottawatomie Giant” took place on April 5, 1915 before a capacity crowd at a racetrack in Havana, Cuba. It was a brutally hot day with the temperature over 100 degrees. At six feet six inches, Willard was one of the tallest heavyweights, and he used his height and reach to great advantage, knocking out Johnson in the 26th round. Photographs show the defeated champ lying on his back on the canvas, shielding his eyes from the blazing sun with an outstretched, gloved hand. Although Johnson continued to box professionally, he never regained the title.

Jess Willard decks Jack Johnson in Havana

Johnson eventually tired of exile and turned himself in to the authorities in July 1920. He served a year in Leavenworth, and returned to Chicago on his release. Reduced to supporting himself by working at carnivals, he insisted he had thrown the fight with Willard. He claimed he had a deal with federal officials to drop the Mann Act charges if he took a dive, but that they had double crossed him.

A close examination of the film of the title match belies this myth. The fight was decided by a knockout after 26 punishing rounds. Johnson managed to stay even until the 20th round, but then he clearly began to tire. When Jess Willard was asked about the claim that the match was fixed, he replied, “If he was going to throw the fight, I wish he’d done it sooner. It was hotter than hell out there.” The knockout punch can be seen in a YouTube clip, and has every appearance of being a solid hit. Most experts agree that Willard won the title legitimately. Nevertheless, Johnson’s claim gained great currency among blacks, and was printed as fact in such black newspapers as The Chicago Defender.

Jack Johnson with Etta Duryea

The malicious-prosecution and fixed-fight myths were further legitimatized by a 1967 Tony-award-winning play, The Great White Hope, which was loosely based on Johnson’s life. James Earl Jones played “Jack Jefferson” on stage and in the screen adaptation made in 1970. Both versions took liberties with the facts and sanitized much of Johnson’s unsavory character. Unlike the belligerent Johnson, “Jefferson” is a largely sympathetic figure exploited by white society. Appearing at the height of the civil rights era, the story was a romanticized liberal indictment of state-sanctioned discrimination. Jefferson is a flawed protagonist, not unlike Othello, whereas the real life Johnson was a heel. The play won a Tony award and Mr. Jones received an Academy Award nomination for the movie performance, leading many people to accept the Hollywood moonshine as fact. It would be much simpler for President Obama to pardon the fictional character than the real man.

Johnson, who was often cited for speeding and reckless driving, died in an automobile accident in 1946. His apologists claim he had driven off in a fury after he was refused service at a segregated lunch counter in North Carolina, and ended up crashing his car. In April, in its report on the efforts to have Johnson pardoned, the Associated Press repeated the myth that he was buried in an anonymous grave. In fact, there is a large monument at the former champion’s grave in the Graceland Cemetery in Chicago. Two of his three wives, the tragic Etta Terry Duryea and, his last wife, Irene Pineau, are buried next to him. The prostitute Lucille Cameron divorced Johnson on grounds of adultery 22 years before his death and is not buried in the same plot.

I predict this most recent attempt to rehabilitate Johnson will succeed. After all, he is just the sort of black person we are supposed to admire: In his prime, he could beat any white man in the ring and he debauched untold numbers of white women. He was the prototype of today’s foul-mouthed athletes who laugh at the very idea of sportsmanship. If, on top of all this, we can be persuaded that vicious, envious white men sent him to jail on false charges we have the perfect hero for our times. Gestures like this cost nothing, and Mr. Obama will have a grand opportunity to lecture us all on racism again.