Victory at Kohima Ridge

Yaroslav Lavrentievich Padvolotskiy, American Renaissance, May 26, 2017

Much has been written about the cataclysmic battles that took place in Europe and the Pacific Ocean during the Second World War, yet very little is known about another theater of operations that was no less important: the British Far East. What knowledgeable people mostly recall about these campaigns is a series of spectacular defeats: the capitulation of Hong Kong and Singapore, and the sinking of HMS Prince of Wales and Repulse by Japanese aircraft. The defeat of the British forces in the Far East during the early months of the Pacific War was by far the worst military loss ever inflicted on the Empire. Within a year, the British were driven out of Malaya and Burma and forced back to India with the Japanese in pursuit. Yet, the Far East would soon see a victory that, according to some experts, surpasses even Waterloo and Quebec. It is known as the Battle of Kohima.

Little has been written about this great victory, but for two torrid months in the most miserable conditions, a small garrison of British and Imperial soldiers faced down an entire Japanese infantry division at ten-to-one odds with few supplies and little fresh water. In the end, they won an impressive victory in the style of Rorke’s Drift that changed the course of the war in Southeast Asia.

The causes of the war in the Pacific were many and long-standing. The most immediate was the American embargo on metal and oil exports to Japan and the closure of the Panama Canal to Japanese shipping because of the Japanese invasion of China and its occupation of French Indochina. The Japanese decided to go to war rather than give in to American pressure.

On December 7th, 1941, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and then turned on the British colonies in the Far East. By Christmas Day, Hong Kong fell, with Malaya verging on capitulation. The Singapore garrison commanded by General Percival fell on February 15th. General Sir Henry Pownall put it thus:

It is a great disaster for British Arms, one of the worst in history, and a great blow to the honour and prestige of the Army. From the beginning to the end of this campaign we have been outmatched by better soldiers.

The blows to British honor and prestige kept coming. On January 20th, the Japanese invaded Burma and captured Rangoon, pushing the British back to Assam by the middle of May. The British had simply been outfought. As historian Charles Messenger notes, “For the survivors of these reverses there was much food for thought and an urgent need to apply their recent experiences to find means of breaking the seeming Japanese invincibility.”

That means came in the form of Major General William Slim, who arrived in the Far East to take command of the Burmese Corps in March 1942. General Slim had held a variety of posts in the British army and had taken successful part in several campaigns. It would be his job to turn defeated, demoralized men into a juggernaut — or be destroyed by the Japanese.

General Slim worked tirelessly to whip his men into shape. The first task was to combat malaria, which was killing more men than the Japanese. Simply by banning shorts and ordering that sleeves be rolled down, General Slim was able to control the disease. He also forced his men to take the anti-malarial drug mepracine, and regularly conducted inspections to see that they did so.

His second task was to force his men to lose their fear of the jungle — a fear the Japanese did not have. General Slim took every man in his headquarters on grueling marches through the jungle until they were confident they could cut through its denseness, and encouraged aggressive patrolling by his troops in “no man’s land” between the lines. Soon, every British and Imperial unit was just as confident in the jungle as the Japanese.

General Slim also realized that every soldier, whether a cook or a clerk, must be a rifleman. Throughout the Burmese campaigns, men in the rear often found themselves defending makeshift positions against ferocious Japanese attacks. General Slim made sure that every man in his army — including his personal staff — could handle weapons.

General Slim also realized that every soldier must feel he is vital. This was especially important because many of his Imperial troops were Indians born into the caste system. On inspection, General Slim emphasized that support personnel were crucial. He likened an army to a clock, saying that every gear is important, no matter how large or small, and if a single gear stops working, the whole machine grinds to a halt. General Slim inspired every soldier to do his duty; they would need all the inspiration and motivation they could muster against the Japanese, who were planning to renew their thrust into the Empire.

By 1944, the Japanese were losing the war in the Pacific to the Americans and to the Royal Navy, which had returned to the theater after evacuating in 1942. The Japanese desperately needed to win in Asia so they could focus their energy on defending Japan from the United States Navy.

General Renya Mutaguchi called for an offensive against the British troops in India. A Japanese victory could inspire the Indians to rise up against the British Raj, and Mutaguchi believed this would force the British to conclude a separate peace. With the British out of the war, China would also have to sue for peace, since it was dependent on supplies delivered across the Himalayas from India.

General Slim wanted to force the Japanese into an offensive across some of the most inhospitable terrain in the world. He and his staff withdrew from Burma to the Imphal Plains in easternmost India. Long supply lines would mean the Japanese Army might be unable to support its troops.

The main Japanese offensive, U go, began in March 1944, when the Japanese pursued the British to Imphal. In an effort to cut the British off from their supply base in Dimapur, 130 miles to the north, General Mutaguchi ordered General Kotuko Sako’s 31st Infantry Division to cut the road to Dimapur by taking Kohima Ridge.

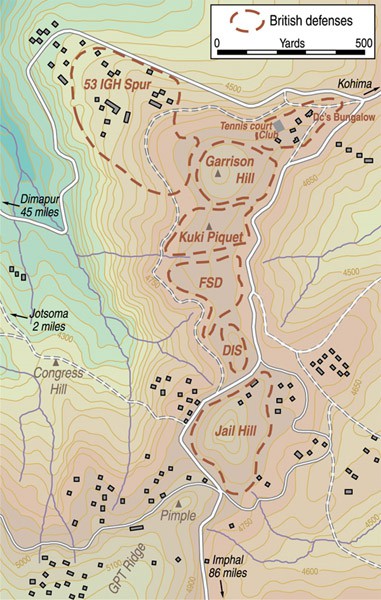

Kohima Ridge overlooks a road that snakes through the jungle and mountains from Dimapur to Imphal, and on this ridge are several hills on which the Japanese offensive would falter. Starting from the north there was the Deputy Commissioner’s Bungalow along with its tennis court, around which some of the fiercest fighting of the entire war took place. Further south along the ridge are Garrison Hill, Kuki Piquet Hill, Fuel Supply Depot Hill, Detail Issue Hill, and Jail Hill. The only fresh drinking water was on the ridge further south.

General Sako began his assault against Burmese troops fighting a fierce delaying action to give the British enough time to fortify Kohima. When General Sako began his attack, Kohima was largely undefended, with mostly convalescents, support personnel, and non-combatants, as well as various British, Indian, Nepalese, and Burmese troops. General Montagu Stopford, commander of the XXXIII Indian Corps, quickly reinforced the defenses by sending the 161st Indian Brigade to Kohima, but only the Queen’s Own Royal West Kent Regiment under Lieutenant Colonel John Laverty and a company of Indians arrived before the Japanese surrounded the garrison. The defense of Kohima would depend on these reinforcements and the convalescents and support personnel already there.

The West Kents and the Imperial soldiers standing with them were outnumbered ten to one, but fought to the death rather than surrender. Capture would have meant being executed, worked to death, or worse. For this reason, British and Imperial soldiers did not have the respect for the Japanese that they did for the Germans. To the defenders, the Japanese were “vermin to be exterminated,” as one British officer put it.

The battle began on April 6th, and the Japanese took the only source of fresh water south of the West Kents. A spring was found on Garrison Hill, but could be reached only at night because of enemy fire by day. A trip to the spring was a walk through hell. Bodies collected everywhere, often staying where they fell, to rot and stink. One private described having to walk and trip over “dead bodies which were black and decaying” in order to reach the well.

Help was on the way in the form of the British 2nd Infantry Division which was advancing down the road toward Kohima from Dimapur. The defenders could also call in artillery support from the 161st brigade, which was cut off two miles away. All the defenders had to do was hold on.

The heaviest, most brutal fighting took place at the tennis court on the northern end of Kohima Ridge. From a position on Garrison Hill overlooking the tennis court, Major John Winstanley, commanding B Company of the West Kents, held out against repeated Japanese assaults. The Japanese would charge across the tennis court and the West Kents would immediately call in support from artillery while gunning down attackers with small arms. Major Winstanley wrote:

[W]e shot them . . . and grenaded them on the Tennis Court. We held the Tennis Court against desperate attacks for five days. We held because we had instant contact by radio with the guns, and the Japs never learned how to surprise us. They used to shout in English as they formed up, ‘give up.’ So we knew when an attack was coming in. One would judge just the right moment to call down gun and mortar fire to catch them as they were launching the attack, and by the time they were approaching us they were decimated. They were not acting intelligently and did the same old stupid thing again and again.

In-between attacks, with lines no more than 50 yards apart, the British and the Japanese lobbed grenades back and forth across the tennis court. The Japanese used direct howitzer fire on the British positions every morning and evening. According to Major Winstanley this “caused mayhem among the wounded lying in open slit trenches on Garrison Hill, so that many were killed or re-wounded.” Doctors had dug a pit covered by a tarpaulin which they used as an operating room, but the wounded waiting outside had to endure endless Japanese attacks and bombardment.

Combat at Kohima was often hand-to-hand. Of many examples of bravery were the actions of Lance Corporal John Pennington Harman of the West Kents, who crossed no man’s land and single-handedly destroyed two Japanese machine-gun nests. After his second foray, Harman walked calmly back while his men yelled at him to run. Harmon said “I got the lot — it was worth it,” before being cut down by machine-gun fire. Lance-Corporal Harman was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.

On the night of April 17–18, after several days of repeated attacks, the Japanese finally took the area around the deputy commissioner’s bungalow and Kuki Piquet. By then it was too late. British reinforcements had arrived and were mounting their own attack. By April 20th, the West Kents were relieved, and the British Army went on the offensive. Supported by artillery and Hawker Hurricane fighter-bombers of 34 Squadron, the British retook their positions. Progress was slow and bloody due to the onset of the monsoon season and dogged Japanese resistance. On May 25, General Kōtoku Satō, his men starving, notified his chain-of-command that if his men did not receive supplies, he would be forced to retreat. Defying stand-and-die orders, General Satō decided to save his men, and withdrew from his remaining positions on May 31.

The British attacked south toward Imphal, and broke the siege on June 22. With the Japanese Army in Burma broken, for the rest of the war, British and Imperial soldiers would only advance.

The battles of Kohim and Imphal are now recognized as the turning points of the Japanese India offensive and are called the “Stalingrad of the East.” In 2013, the British National Army Museum named these engagements “Britain’s Greatest Battle.” The key to this victory was the heroic defense by the West Kents on Kohima Ridge. Like their predecessors who faced the Imperial Guard at Waterloo and like their comrades who repelled 5,000 Zulu warriors at Rorke’s Drift, British soldiers once again displayed the martial characteristics that made them so renowned throughout the world.

The Defence of Rorke’s Drift, by Alphonse de Neuville (1880)

* * *

Further reading

Autobiography of the British Soldier: From Agincourt to Basra, in His Own Words. John Lewis Stempel. Headline Review.

Burma: The Longest War 1941-45. Louis Allen. London: Phoenix Press.

Defeat into Victory. Field Marshal Sir William Slim. London: Cassell.

History of the British Army. Charles Messenger. Bramley Books.