Marketing Blackness to Cure Racial Strife

Joseph Kay, American Renaissance, April 11, 2022

Blacks are “hot.” A foreign visitor would assume that African Americans must be at least half the US population and are doing exceptionally well. From TV commercials to glamorous fashion magazines, from recipients of prestigious awards to TV celebrities and political commentators, blacks are everywhere.

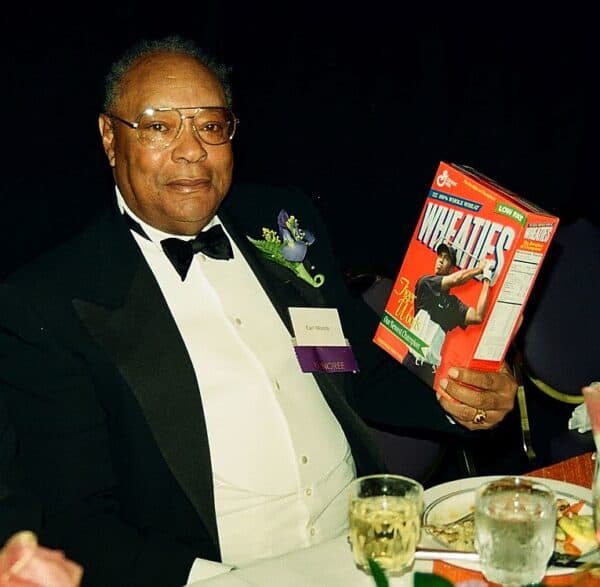

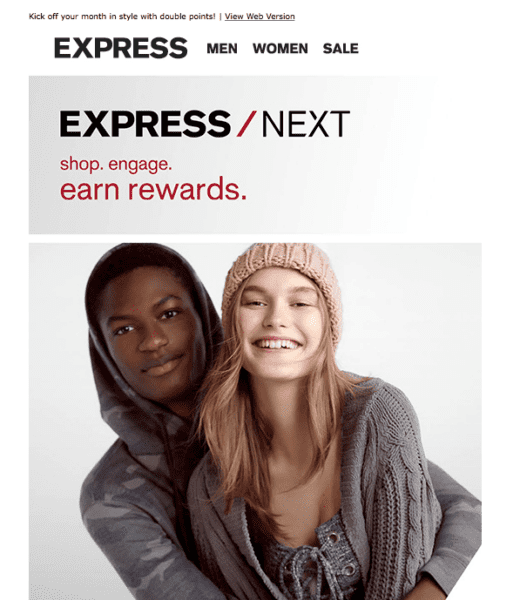

And they are portrayed in the most favorable light possible. TV commercials, for example, depict blacks (especially sharply dressed black women) driving luxury cars while credit card commercials depict chic blacks dining in fancy restaurants or shopping in boutiques. Catalogs from WASPy stores such as Brooks Bros. feature black models. A foreigner would assume that blacks were among the most affluent of all Americans. Many — perhaps most — of these portrayals also show them in happy, middle-class families and in white collar jobs. This is a far cry from the era when blacks appeared in ads, if at all, as athletes on the Wheaties cereal box or entertainers. The once Great Taboo — black men together white women — has now almost become a cliché on TV.

Earl Woods holding a box of Wheaties with his son, Tiger Woods, on it. (Credit Image: John Mathew Smith via Flickr)

Sometimes, there is no effort to “whiten” blacks by dressing them conservatively or having them speak proper English. Some even have lower-class ghetto-type hairdos. This is not just the acceptance of blacks as rich and important; it showcases their “culture.”

Why the dramatic change? Has American business finally recognized the buying power of this long-neglected demographic? Conceivably, but unlikely and, if so, why so suddenly? The in-your-face blackness mania hardly existed five years ago. And it is hard to believe that commercials starring blacks help sell expensive Lincolns or that millions of whites will now switch to credit cards favored by consumption-happy blacks.

There is a better explanation. What we see is an alternative reality manufactured to replace the bad side of black behavior usually suppressed by the media. Real-world reality is soaring violent black crime, iPhone or surveillance camera videos of blacks fighting each other in restaurants and airports, blatant smash-and-grab crime, feral blacks just hanging out or dealing drugs, as well as all the other black mischief that only occasionally goes public.

Black violence is so common that when the media do report a gruesome crime or a mass looting of a store, it’s safe to assume the perpetrators were black. Euphemisms notwithstanding — youths, members of an under-served community, minorities, the marginalized – people know the truth. White evildoers make the front page.

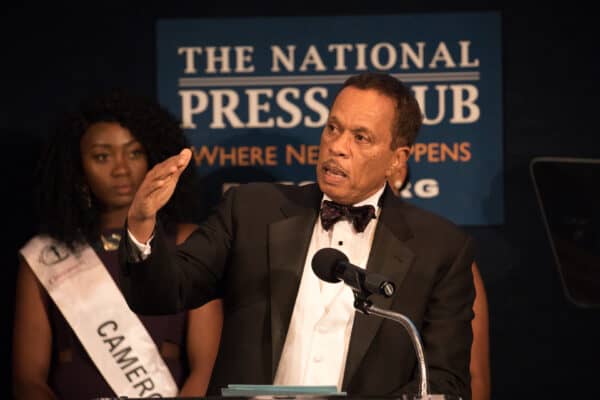

The construction of this alternative universe is not an organized conspiracy. Nor is it likely that the mass media are convinced that hiring a few black pundits like Juan Williams will reduce inner-city shootings. The forces behind it are unspoken and probably unconscious. This is a push/pull cultural dynamic in which the more obvious bad black behavior becomes, the greater the need to convince ordinary Americans that blacks are just like us. Thus, the real product in a pharmaceutical commercial with a black doctor is not the drug; it is respectable blackness. If black misbehavior returned to manageable, 1950s levels, TV directors might no longer feel the urge to hire blacks for car-insurance commercials.

Juan Williams, Television Broadcast Journalist of the Year, speaks at Vote It Loud’s second annual Multicultural Media Correspondents Dinner at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. on Thursday, May 25, 2017. (Credit Image: © Cheriss May / NurPhoto via ZUMA Press)

What’s gained by this? Rather than re-impose mass incarceration and similar punitive measures, just manufacture a reality “demonstrating” that what is on the local news is totally atypical. Ignore surveillance cameras; trust the world of TV commercials instead. Perhaps the aim is that if enough Americans accept this Potemkin Village alternative universe, blacks will reform, and America will return to some fantasy recollection of yesteryear.

Surely, the hope is that this fantasy world will cure whites of stereotypes and help blacks behave better. Commercials will fight racism by making white people think blacks are so wonderful that it would be an honor for one to marry your daughter. Black viewers are probably a less important target, but glamorous TV blacks are probably supposed to be “positive role models.”

This cosmetic approach is futile, but makes sense emotionally. It spares elected officials the need to be tough on crime, even though many blacks and even rich liberals would like that. At the same time, media and business executives can enjoy the moral high of promoting diversity and inclusion. It is also cheap — unlike a Manhattan Project to rebuild cities.

Substituting public relations for difficult problems is common in business. Marketing departments often override engineers, because running a few ads with a catchy jingle is easier than fixing a lousy product.

A notable illustration of this was how General Motors responded to its declining market share beginning in the 1960s. In the early 60s GM was still dominant but it was launching one troubled car after the next — the Corvair, Vega, Chevrolet Citation, Saturn among others — while earning a reputation for shoddy workmanship. Ralph Nader’s Unsafe at Any Speed was a bestseller, and for good reason. By the 1970s, this set the stage for cheaper and better-made Japanese and German cars.

GM executives poo-pooed the imports and tried public-relations fixes to their woes. Between 1974 and 2011, for example, GM’s TV commercials featured a “Mr. Goodwrench,” a nerdy mechanic who assured audiences that great service awaited them when they took their troubled cars to the local GM dealer. Reality was the opposite. David Halberstam notes in The Reckoning that dealers overcharged customers to compensate for having to fix problems covered by warranties.

A similar PR effort was the “GM Mark of Excellence” campaign that ran from the mid-80s to the 90s and was briefly revived from 2006 to 2009. This motto was plastered on cars as if a slogan could compete with Japanese manufacturing. The campaign included the phrase, “Nobody sweats the details like General Motors,” but GM even acknowledged its quality problems when its ill-fated Saturn was hailed as “a Japanese-style” car. Nothing reversed the slide, and on June 1, 2009, GM declared bankruptcy. Only a federal bailout saved it.

Will today’s infatuation with blackness do any good? Public relations cannot make people believe 2+2=5. Furthermore, even in this age of the mysterious power of “systemic racism,” there is little or no relationship between what white people think and what black people do. The totalitarian Soviet Union failed to convince its citizens that it was the long-awaited Workers’ Paradise. Hiring black actors to portray doctors will not convince whites that a black MD is as competent as a white one. TV commercials heavy on artificial diversity will not hide unpleasant realities.

So, what’s next? Since black behavior won’t change, we can expect ever more quack cures. Both Hollywood and the NFL have already replaced voluntary racial “targets” with quotas. Such is human nature: If Plan A fails, try Plan B, and if that fails, try Plan C; people feel better for trying.

There are limits to what PR can achieve. Americans exasperated by dreadful GM cars turned to imports. Those surveillance camera videos are a lot more convincing than Cadillac commercials.