Waukesha Christmas-Parade Trial, Days Eight, Nine, and Ten

Anastasia Katz, American Renaissance, October 20, 2022

The trial of Darrell Brooks, the black man who drove a car through the Waukesha Christmas parade, continued on October 17, with testimony from people who saw Mr. Brooks after he left his mother’s red SUV — heavily damaged from hitting men, women, and children — in a driveway, not far from the parade route. Mr. Brooks had been wearing a gray hoodie and blue flip flops when he drove through the parade, but witnesses who saw him later said he was wearing a red T-shirt and was barefoot — not appropriate clothing for cold weather.

Sean Backler, a white man, found Mr. Brooks trespassing in his yard, and thought something was “off.” Mr. Brooks asked him to call an Uber for him. Mr. Backler told Mr. Brooks to leave and called the police. When he later saw the mugshot of the parade-attack suspect, he knew it was the same man.

Mr. Brooks was next spotted by Domanic Caproon, another white man, who said the defendant came up his driveway and asked for a phone to call an Uber. Mr. Brooks lifted his shirt to show he was unarmed. Mr. Caproon let Mr. Brooks use his phone and thought he was calling an Uber. Later, Mr. Caproon got a call back from a lady who was “not an Uber.”

Erin Cordes, a white woman, had been at the parade and saw a police officer fire three times at the red SUV as it drove through, but she did not get a good look at the driver. She later saw Mr. Brooks come out of the bushes from behind two houses. She let him use her phone and he called his mother, asking her to call an Uber. Mrs. Cordes noted “a sense of urgency.” Mr. Brooks asked her if she knew where he could warm up, and she pointed toward the lobby of a nearby building. Surveillance video from inside the building showed Mr. Brooks walking up to the lobby doors.

Anthony Winters, a black Lyft driver, responded to a ride request at the building. He said, “The fare came in for Dawn,” which is Mr. Brooks’s mother’s first name. The customer was a no-show, so he canceled the call after waiting for 10 minutes.

A young white man named Daniel Rider testified that Darrell Brooks showed up on his front porch, where he was captured on video by a Ring doorbell camera. Mr. Brooks told him he was homeless and cold, and was waiting for an Uber. Mr. Rider invited him in, made him a sandwich, and let him use his phone to call his mother. The Uber seemed to be taking a long time, and when Mr. Rider noticed several police cars patrolling his street, he began to worry and asked Mr. Brooks to leave. Mr. Brooks went outside, but soon asked to be let back in, saying he had left something inside. Mr. Rider kept the door shut, and testified that Mr. Brooks had left nothing behind.

Officer Rebecca Carpenter, a white police officer from a town neighboring Waukesha, heard radio traffic asking for help at the parade. Later, she took a call about a suspicious man going door to door asking to use a phone. When she arrived and spotted Mr. Brooks, she thought she was drunk.

When Assistant DA Zachary Witchow asked Officer Carpenter to identify Mr. Brooks in court, Mr. Brooks interrupted, saying that he doesn’t identify by that name. Mr. Brooks has said this many times during the course of the trial.

The prosecution played Officer Carpenter’s bodycam footage, which showed Mr. Brooks lying belly-down on the ground, where she had ordered him, turning his face up to answer questions. He said he was Darrell Brooks — twice. He also had ID on him that said he was Darrell Brooks. Officer Carpenter asked him where his shoes were, and Mr. Brooks lied, saying they were in Mr. Rider’s house. She asked where he had come from, and he said “I was coming from that parade.”

Officer Carpenter did not yet know that he was the suspect in the hit-and-run. She let him stand up, and she and Officer Garrett Luling, who had joined her, checked him for weapons. Officer Carpenter brought Mr. Brooks to the squad car because “he was not dressed for the weather.”

Officer Luling told the court that when he responded to a call, Officer Carpenter already had Mr. Brooks cuffed and on the ground. He said he asked Mr. Brooks what his name was, but Mr. Brooks interrupted his testimony, saying, “Objection. That’s not what it says on the video,” although the video showed Officer Luling asking Mr. Brooks his name. Officer Luling knew that documents with the name “Darrell Brooks” were found in the car that had run through the parade. He told Mr. Brooks he was being detained because he matched the description of the suspect.

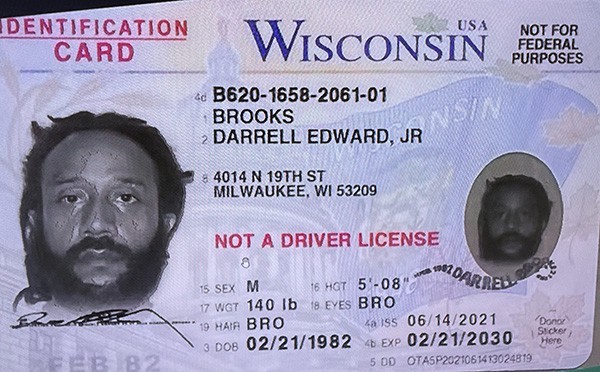

Detective Jay Carpenter, a white man, had marched with the Waukesha PD Color Guard at the parade. He heard about the hit-and-run when he was back at the station, and responded to a dispatch about a possible suspect “nearly identical to the driver.” Mr. Brooks was already being held when he arrived. The detective took the items Officer Luling found in Mr. Brooks’ pocket: a Wisconsin non-driver ID with the name Darrell Edward Brooks Jr., credit and debit cards, and a Georgia EBT card belonging to his girlfriend, Erika Patterson, who had come to visit him. Mr. Brooks did not have a driver’s license.

Mr. Brooks complained of pain in his knee and shoulder, and claimed the arresting officer slammed him to the ground. Officer Carpenter’s bodycam video shows that she ordered Mr. Brooks to lie down, and he complied. He was taken to the Waukesha Memorial Hospital and was medically cleared after an x-ray.

Draelon Leija, a black officer with the Waukesha PD, testified that he was sent to the hospital with orders to take Mr. Brooks to the police station. As they passed the parade location where there were still many officers, Mr. Brooks said, “Damn, it looks like they were doing something heavy.”

At the police station, Mr. Brooks asked to call his daughter, but Officer Leija would not allow that because Mr. Brooks had to see a detective first. Mr. Brooks complained that the lights in the holding cell were too bright, but the officer watched him fall asleep with his head under a blanket.

The next trial day, Tuesday, Detective Carpenter came back to court to continue his testimony with audio-visual evidence. First was an audio recording from the hospital. An FBI agent had been sent because this was a possible terrorist attack, and Mr. Brooks said, “For real? The FBI? . . . This is the first time I’ve ever seen an FBI agent in real life.”

Detective Carpenter described Mr. Brooks’s demeanor as “very calm” during most of the interrogation, except he was “nervous” because the FBI agent was present. The jury watched video of the questioning. Mr. Brooks said he was a high school graduate and was unemployed since being laid off from a job at a sheet metal company during the 2020 Covid scare. He told police he had three children, ages 18, 14 and seven.

Detective Carpenter read Mr. Brooks his rights, then said he wanted to hear Mr. Brooks’ side of the story. He asked why Mr. Brooks was going door to door asking for help. Mr. Brooks said, “Unfortunately, I wouldn’t have had to do that if I had better decisions, but I’m not going to point the finger. I’m a grown man, I make my own decisions, but I didn’t think.”

Detective Carpenter told him that his girlfriend, Miss Patterson, claimed he abused her. Mr. Brooks got angry: “Why would you put me in that situation and then you know we’re gonna be together anyway?” He said he had asked Miss Patterson to hold $350 for him, and he got in touch with her on social media and asked to meet her to get his money back. He told the detective that she wanted to hang out and have sex, but he just wanted to get his money and leave.

The detective asked Mr. Brooks how he got to the neighborhood where he was arrested; Mr. Brooks claimed that he walked. “I didn’t drive at all.” Later in the questioning, he claimed that a friend drove him there in a tan Kia, and he didn’t want to name the friend because he didn’t want to get him in trouble.

In the interrogation video, Mr. Brooks was gesturing as he talked, and Detective Carpenter pointed out that his supposedly injured shoulder had full range of motion.

One of the witnesses on Tuesday was called by Mr. Brooks as a defense witness. Although the state had not yet rested, this witness was taken out of order because he needed a Spanish interpreter. During Mr. Brooks’ direct, Juan Marquez said he felt a vehicle hit his leg while he was marching in the parade with Catholic Communities. He went to the hospital, and was interviewed by an FBI agent there. Mr. Brooks asked him if he remembered telling the agent that he had been hit by a black truck, but Mr. Marquez said he did not remember. The best Mr. Brooks could do was get Mr. Marquez to say that he did not see the vehicle that hit him.

Deputy DA Lesli Boese conducted the cross examination, and Mr. Brooks objected to every question. Mr. Marquez testified that he had no warning that the car was coming; he did not hear a horn honking. After he was hit, he landed 15–20 feet away, and he had a broken leg and torn ligaments.

Mr. Brooks was not happy that the state turned his witness against him, and that all of his objections were overruled. He interrupted, saying, “That’s judicial misconduct,” but the judge ignored him, and Miss Boese kept questioning. When Mr. Marquez said that his injuries required two surgeries, Mr. Brooks said, “That’s not going to work, either.”

Judge Jennifer Dorow told him to stop the commentary, and he replied, “I’m gonna say what I want to.”

The judge sent the jury out, and he repeated “judicial misconduct” as they left the courtroom. He said to the judge, “I’m not gonna let you fix this trial because you don’t want to tell the truth to the jury.”

With the jury out, Judge Dorow said, “Please stop.” She told him he was being disrespectful and disruptive.

“You’re saying someone’s being disruptive because they want the truth to be out there. Man, quit it!”

She told him that continued interruptions would mean he would be removed from the courtroom. He kept interrupting, so the judge had him taken to another courtroom. She has put him there before when he wouldn’t behave. The judge stated for the record that she would not find Mr. Brooks in contempt because that would reward his bad behavior by delaying the trial. She explained that Mr. Brooks can watch the trial by video and can speak, but she can mute him any time.

When the jury returned, Judge Dorow asked if Mr. Brooks had any redirect for Mr. Marquez. He was reading a book and not paying attention, so she asked him three times. He had no more questions and Mr. Marquez and the interpreter were dismissed.

On Wednesday, October 19, the tenth day of trial, the state asked that the jury be shown the vehicle Mr. Brooks drove through the parade. He objected that it was not relevant and the judge overruled. The jurors will be taken to a garage in a secure location, where they can walk around the car. The judge told Mr. Brooks that he has a right to be there, and asked if he wanted to go. Mr. Brooks said he did not, but made a fuss because he didn’t understand how jurors could look at the car without him there.

He asked how he could attend if he changed his mind. Mr. Brooks is in shackles, but they are hidden from the jury because it could influence their verdict. Judge Dorow said he would wear a suit and would be unshackled, but accompanied by bailiffs. Mr. Brooks said that the shackles are a “shock device” and he asked why he would have to have “ankle shocks” on him. The judge said his shackles are not shock devices.

Kyle Becker, a Waukesha police officer, testified that he was part of the team searching the area where Mr. Brooks was arrested. Officer Becker found the gray hooded sweatshirt and blue shoes Mr. Brooks was wearing when he drove through the parade. The shoes were found on opposite sides of a fence, and the officer thought they must have fallen off when Mr. Brooks climbed the fence. The sweatshirt was in a children’s play house in a backyard.

Officer Kyle Becker holding Darrell Brooks’s shoes.

On cross-examination, Mr. Brooks asked Officer Becker if he had chased a suspect and watched him climb the fence. Officer Becker had not.

Detective Justin Rowe testified that he gathered surveillance videos from the area where Mr. Brooks was arrested, and used them to put together a map that showed where Mr. Brooks went after the parade. The jury viewed these videos and his map. Mr. Brooks made many baseless objections.

The state called Ryan Schultz of the Wisconsin State Patrol, who specializes in inspecting vehicles involved in crashes. He examined the 2010 red Ford Escape and found no brake failure. The power steering was also fully functional, and there was no problem with the gas pedal.

On cross, Mr. Brooks had Mr. Schultz repeat his testimony about parts of the car that needed maintenance (for example, there was a coolant leak), but none would have made Mr. Brooks lose control.

On the previous day, the judge had to remove Mr. Brooks from the courtroom for bad behavior, but he was now back in the main courtroom. He continued to be disruptive. Judge Dorow told him not to make disparaging comments under his breath.

“If it was disparaging, what did I say?” Mr. Brooks asked.

“You say things like, ‘It’s not fair,’ or you make noises like you’re disgusted with the ruling,” the judge said. She reminded him, as she has had to do every day of trial, that he needs to observe decorum.

Deputy DA Lesli Boese added that Brooks had said, “Stop trying to be slick!” a comment she found particularly disrespectful.

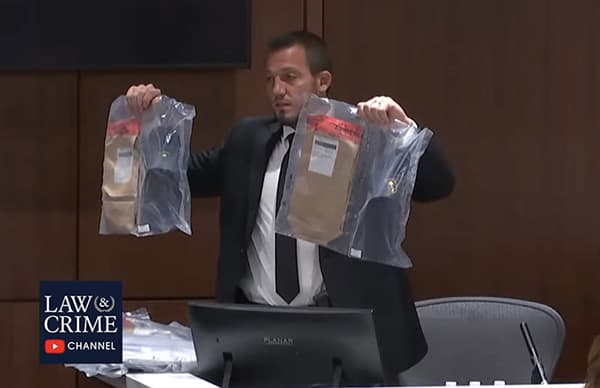

Chris Johnson, an investigator at the Wisconsin State Crime Lab, testified about processing the red SUV. He first removed several items: gloves, a winter hat, and a Christmas headband with LED lights that was wrapped around the rearview mirror. He swabbed the inside and outside for DNA. “In this case,” Mr. Johnson said, “the vehicle is the crime scene.”

He noted “bullet defects” caused when a police officer tried to stop Mr. Brooks by firing three times. One bullet hit the roof, another entered through the rear of the car and lodged in the baggage area, and the third entered through the rear passenger window and exited through the windshield.

A bullet hole in the window of the red SUV.

The last witness of the day was biochemist Trevor Naleid, a forensic analyst at the Wisconsin State Crime Lab, who testified about the DNA. He found that the steering wheel and gear shift had DNA from both Darrell Brooks and his girlfriend, Erika Patterson. Mr. Brooks’s gray sweatshirt also had his and Miss Patterson’s DNA. A hat found on the SUV contained the DNA of Wilhelm Hospel, one of the six people who died after Darrell Brooks ran them over.

After the jury was dismissed for the day, the state said it will bring back a witness, Detective Casey, and then rest. Judge Dorow told Mr. Brooks to be prepared to make his opening statement. At the beginning of the trial, he deferred his opening until after the state rested. The judge advised him that an opening is “the roadmap;” she expects him to use phrases like “the evidence will show.” She warned him that arguments should be saved for closing.

The judge asked Mr. Brooks if he is planning on testifying. He has not yet decided.