Zora Neale Hurston: A Black Woman We Can Admire

Jared Taylor, American Renaissance, June 30, 2023

She would have been appalled by today’s blacks.

This video is available on Rumble, BitChute, and Odysee.

Years ago, I learned of a black woman, back in the 1920s, who had said, “Slavery is the price I paid for civilization.” Slavery might have been awful for her ancestors, but it got them out of Africa, and that was why she was living in the United States – a civilized country. I made a note of her name: Zora Neale Hurston. I told myself I would find out about her, but I never did.

Now, with blacks appearing actually to believe they deserve millions of dollars just because they’re black, I finally looked her up, and I’m glad I did.

Credit Image: © Richard B. Levine/Levine Roberts via ZUMA Press

She was a gifted writer and a remarkable woman. She never asked for special treatment, only for a chance to succeed on her own. To the end of her life, even as blacks became more petulant and demanding, she refused to be part of what she called “the sobbing school of Negrohood.”

Zora Neale Hurston was born in 1891 and grew up in one of the first incorporated all-black towns in America, Eatonville, Florida.

Her father was a preacher and was elected mayor. She earned a degree at Howard University, where she began her writing career and co-founded the school newspaper. In 1925, she got a scholarship to Barnard College, the girls’ campus of Columbia University. She studied anthropology under Franz Boaz and worked with Margaret Meade and Ruth Benedict — without joining the “sobbing school of Negrohood.”

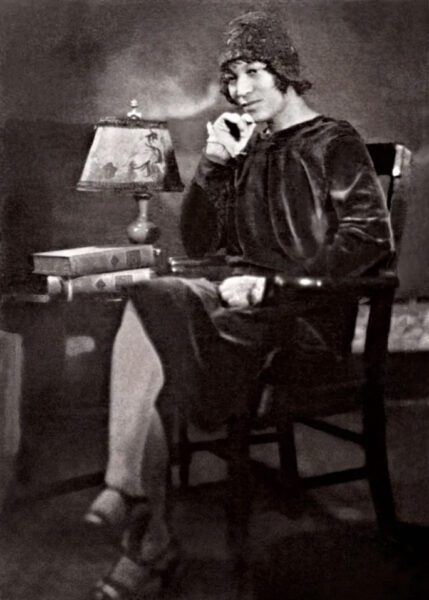

She did fieldwork in anthropology and, as part of what is called the Harlem Renaissance, wrote novels, short stories, and even plays. Here she is, on the very right, with the cast of a play she wrote, called The Great Day.

She had a lovely writing style and always stood up for women — she was an early feminist — but she didn’t toe the line on race.

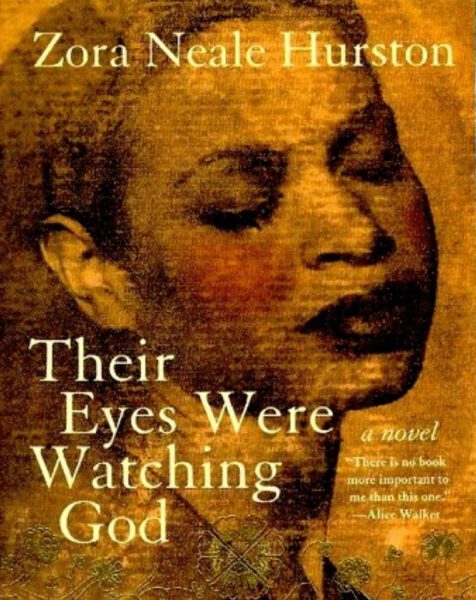

Her best known novel, published in 1937, is Their Eyes Were Watching God, which she wrote in seven weeks while she was researching voodoo in Haiti.

Here she is at a book fair right about the time of publication.

In a 2022 article, Reason magazine called the book “a gripping semi-autobiographical portrait of a woman’s odyssey in search of romantic and personal freedom. It is now justly recognized as one of the greatest American novels of the 20th century.”

I wouldn’t go that far, but it has some nice passages. Here’s one: “All gods who receive homage are cruel. All gods dispense suffering without reason. . . . Through indiscriminate suffering men know fear and fear is the most divine emotion. . . . Half-gods are worshipped in wine and flowers. Real gods require blood.”

All the important characters in the book are black, and they speak in Negro dialect, as in: “Two things everybody’s got tuh do fuh theyselves. They got tuh go tuh God, and they got tuh find out about livin’ fuh theyselves.”

There is no “racism” in the novel. In fact, when the heroine kills her lover in self-defense, a sympathetic all-white jury finds her innocent.

All this infuriated blacks. They didn’t care that it was a moving story about human emotions. They thought writing in dialect degraded blacks, and that there was no point to a novel without evil white people. The author Richard Wright wrote that Hurston had “no message, no thought,” and that she was performing for white people in a style that “evokes a piteous smile on the lips of the ‘superior’ race.”

That wasn’t it at all. As she said about an earlier novel, “The story is about Negroes but it could be about anybody. . . . It is the first time that a Negro story has been offered without special pleading. The characters in the story are seen in relation to themselves and not in relation to the whites . . . .”

In 1942, Hurston wrote an autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road.

The black novelist Maya Angelou, who wrote an introduction, complained that it “does not mention even one unpleasant racial incident.” Scandalous. A black woman with no sob stories.

Which brings us to what Hurston wrote specifically about race. How’s this?

“Certain words and phrases mean one thing to Dixie and something entirely different outside. For example, segregation is interpreted as racial hatred by outsiders but not so in the South, where it merely means separate social activities and connections — not hatred of Negro individuals.”

The line about slavery that first caught my eye is from an essay called “How It Feels to Be Colored Me,” published in 1928.

It’s short and well worth reading. Here are some passages:

“I am not tragically colored. There is no great sorrow dammed up in my soul, nor lurking behind my eyes. I do not mind at all. I do not belong to the sobbing school of Negrohood.”

Here’s another passage:

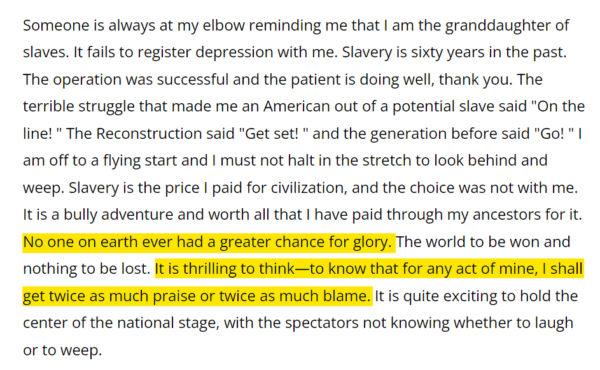

“Someone is always at my elbow reminding me that I am the granddaughter of slaves. It fails to register depression with me. Slavery is sixty years in the past. The operation was successful, and the patient is doing well, thank you.”

Slavery is now 160 years in the past, and blacks sob about it more than ever. And here is the context of the line about slavery:

“Slavery is the price I paid for civilization, and the choice was not with me. It is a bully adventure and worth all that I have paid through my ancestors for it.” Living in the civilized United States rather than Africa is such a “bully adventure” it’s worth whatever her ancestors may have suffered.

Hurston continued writing into the 1950s, but editors wanted to publish sobbing Negroes, and she refused to sob.

She mocked the way blacks approached whites: “ ‘We were brought here against our will. We were held as slaves for two hundred and forty-six years. We are in no way responsible for anything. We are dependents. We are due something from the labor of our ancestors. Look upon us with pity and give!’ ”

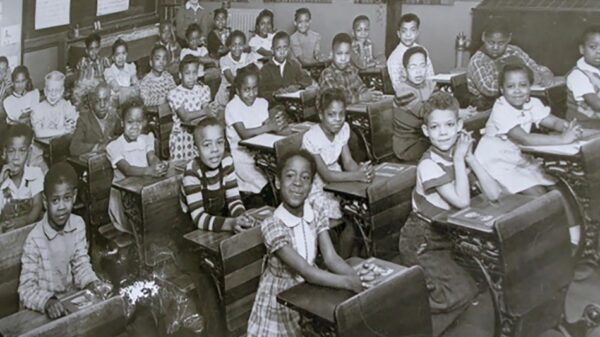

One of the last things Hurston published was only a letter to the editor. It was about the 1954 Brown v Board Supreme Court decision that integrated schools. You wouldn’t have found her in a lovey-dovey photo op on the courthouse steps.

“How much satisfaction can I get from a court order for somebody to associate with me who does not wish me near them?” She asked. “I regard the ruling of the U.S. Supreme Court as insulting.” She mocked “the belief that there is no greater delight to Negroes than the physical association with whites.”

Remarkably, she even saw that the court was brazenly taking power from the people. “A precedent has been established,” she wrote. “Govt by fiat can replace the constitution.” And that is what happened. Even today, how many so-called conservatives would dare call Brown the brutal power-grab it so clearly was?

You can understand why, by the time Hurston died in 1960, she was penniless and forgotten. “I am so put together that I do not have much of a herd instinct,” she wrote. “Or if I must be connected with the flock, let me be the shepherd my own self.”

But I think these are the best lines she ever wrote: “No one on earth ever had a greater chance for glory. . . . It is thrilling to think — to know that for any act of mine, I shall get twice as much praise or twice as much blame.”

What a way to think about being black in the Jim Crow South! She knew that some people might hold her blackness against her, but also that her successes would be twice as sweet. “No one on earth ever had a greater chance for glory.” What a spirited sentiment! A hundred years later, look at today’s blacks: coddled, petted, slobbered over — and they still think they are oh, so oppressed. Hurston would spit on them.

Credit Image: © Thomas Krych/ZUMA Press Wire

And she was right about “twice the praise.” In an article about her just last year, the New York Times wrote: “her words make it impossible for readers to consider her anything but one of the intellectual giants of the 20th century.” Whew. Let that sink in.

“Despite facing sexism, racism and general ignorance . . . .”

Of course. The Times tells us she was fighting white racists her whole life — except it was black men who insulted her and ran her down. And what’s that about “general ignorance”? Coming from the Times, it makes you laugh, doesn’t it?

I think Zora Neal Hurston would have gotten the joke.