A Mass Incarceration Mystery

Eli Hager, The Marshall Project, December 15, 2017

{snip}

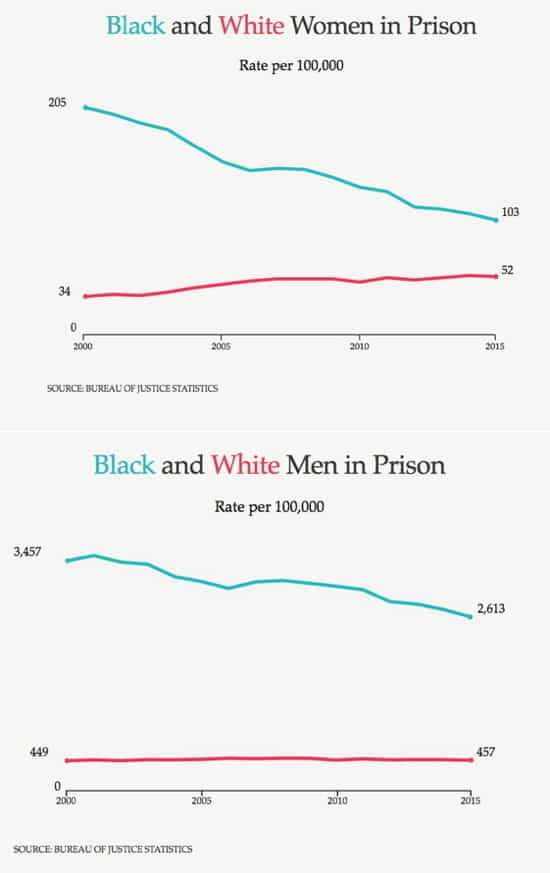

Between 2000 and 2015, the imprisonment rate of black men dropped by more than 24 percent. At the same time, the white male rate increased slightly, the BJS [Bureau of Justice Statistics] numbers indicate.

Among women, the trend is even more dramatic. From 2000 to 2015, the black female imprisonment rate dropped by nearly 50 percent; during the same period, the white female rate shot upward by 53 percent. As the nonprofit Sentencing Project has pointed out, the racial disparity between black and white women’s incarceration was once 6 to 1. Now it’s 2 to 1.

Similar patterns appear to hold for local jails, although the data are less reliable given the “churn” of inmates into and out of those facilities. Since 2000, the total number of black people in local detention has decreased from 256,300 to 243,400, according to BJS; meanwhile, the number of whites rose from 260,500 to 335,100. The charts below from the Vera Institute of Justice also reveal significant drops in the jailing of blacks from New York to Los Angeles, coinciding with little change for whites. (In both the prison and jail data, the total number of incarcerated Latinos has increased, but their actual incarceration rate has remained steady or also fallen, attributable to their increasing numbers in the U.S. population generally.)

Taken together, these statistics change the narrative of mass incarceration, and that may be one reason why the data has been widely overlooked in policy debates. The narrowing of the gap between white and black incarceration rates is “definitely optimistic news,” said John Pfaff, a law professor at Fordham University and an expert on trends in prison statistics. “But the racial disparity remains so vast that it’s pretty hard to celebrate. How exactly do you talk about ‘less horrific?’”

According to Pfaff, “Our inability to explain it suggests how poorly we understand the mechanics behind incarceration in general.” In other words, how much of any shift in the imprisonment rate can be attributed to changes in demographics, crime rates, policing, prosecutors, sentencing laws and jail admissions versus lengths of stay? And is it even possible to know, empirically, whether specific reforms, such as implicit bias training, are having an effect on the trend line?

{snip}

[Here] are four (not mutually exclusive or exhaustive) theories, compiled from our research and interviews with prison system experts, to explain the nearly two-decades-long narrowing of the racial gap in incarceration.

1) Crime, arrests and incarceration are declining overall.

Those decreases benefit the most incarcerated group: African Americans. Crime rates have been on the decline since just after 1990, as have arrests. Given that both measures disproportionately affect the black community, one theory goes, the overall drop should shrink the racial gap in incarceration, too.

{snip}

2) The war on drugs has shifted its focus from crack and marijuana to meth and opioids.

{snip}

But the narrowing of that gap since the mid-1990s — right around the passage of the 1994 crime bill, which is often blamed for the spike in black incarceration — has been nearly as sharp. And in 2000, something else happened: White people started getting locked up for drugs more often. From 2000 to 2009, the black imprisonment rate for drug offenses fell by 16 percent. For white people, it climbed by nearly 27 percent, according to BJS.

{snip}

3) White people have also faced declining socioeconomic prospects, leading to more criminal justice involvement.

Starting around 2000, whites started going to prison more often for property offenses: robbery, burglary, theft, motor vehicle theft, forgery, counterfeiting and selling or buying stolen property, often categorized as crimes of poverty. From 2000 to 2009, black incarceration for those crimes dropped nine percent, the BJS numbers show. It went up by 21 percent for whites.

{snip}

One much discussed study by economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton found that between 1998 and 2013 — precisely when these racial shifts in incarceration were occurring — white Americans saw their rates of mortality, suicide and alcohol and drug abuse spike acutely.

{snip}

4) Criminal justice reform has been happening in cities, where more black people live, but not in rural areas.

{snip}

Yet this is a tale of two Americas: urban and rural. From 2006 to 2014, according to a recent analysis by the New York Times, annual prison admissions plummeted in major cities such as Los Angeles and Brooklyn, due largely to criminal justice reform. But in counties with fewer than 100,000 people, the incarceration numbers have actually risen even as crime declined.

People in rural districts are now 50 percent more likely to be sent to prison than are city dwellers, as local prosecutors and judges there have largely avoided the current wave of reform. New York offers an illustrative example. It reduced its incarcerated population more than any other state during the 2000s — but almost entirely through reductions in the far more diverse New York City, not in the whiter and more sparsely populated areas of the state.

{snip}

Even more troubling, racial divides in the juvenile justice system are getting significantly worse. In 2003, black youth were incarcerated at 3.7 times the rate of white youth; by 2013, that number had grown to 4.3.

{snip}