The Racial Tensions Lurking Under the Surface of American Society

Robert P. Jones, The Atlantic, May 12, 2014

{snip}

Well before the election of the first black president in 2008, the condemnation of direct and open expressions of racism had become a social norm. While the fading acceptability of openly racist attitudes is to be celebrated, it clearly does not mean that race no longer matters or that racial tensions and anxieties have disappeared. In her scathing dissent in the Michigan case, Justice Sonia Sotomayor chastised her colleagues for downplaying the continuing significance of race:

Race matters . . . . This refusal to accept the stark reality that race matters is regrettable. The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to speak openly and candidly on the subject of race, and to apply the Constitution with eyes open to the unfortunate effects of centuries of racial discrimination.

For civil-rights activists, the challenge is that the open racism of the past may transmute into what Ta-Nehisi Coates describes as an “elegant racism” that is less visible and that “disguises itself in the national vocabulary, avoids epithets and didacticism,” For researchers, journalists, and policymakers, the new challenge is that this positive social norm may make the public less willing to speak openly and candidly about race, a problem social scientists call “social-desirability bias.”

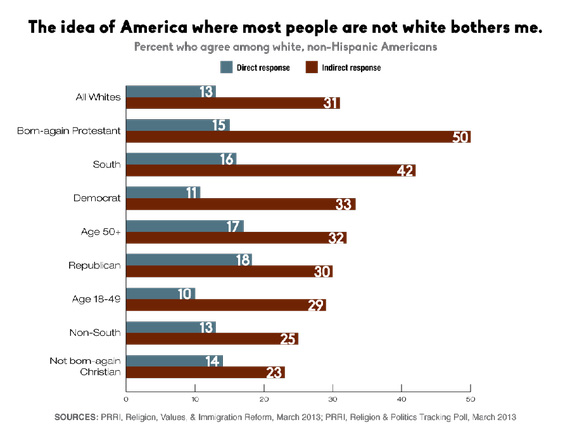

Recent research reveals that social-desirability bias remains active in the measurement of white anxieties about the changing racial composition of the country. In early 2013, the Public Religion Research Institute team set up a controlled survey experiment designed to assess anxieties concerning the changing racial makeup of the country. First, we asked respondents to tell telephone interviewers whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement, “The idea of an America where most people are not white bothers me.” Among whites, 13 percent admitted to an interviewer that the idea of a majority-minority America bothers them. There was only modest variation among white subgroups, ranging from 10 percent of younger whites young than 50 years of age at the low end to 18 percent of white Republicans at the high end who said an America that is not mostly white concerns them.

Next, we employed a technique called a list experiment, which is designed to allow respondents to indirectly express their views on sensitive subjects. We divided the survey respondents into two demographically identical groups and asked each group to tell us how many, but not which specific items from a list bothered them. One group was designated as a control group and received three control statements, while the other group was designated as a treatment group and received the same three control statements plus a fourth statement that read, “An America that is not mostly white.” Because the control and treatment groups were demographically identical, any variation in the average number of statements chosen between the groups is solely attributable to respondents in the treatment group picking the treatment statement. For any subgroup (but not for an individual), then, one can statistically estimate the proportion of respondents choosing the treatment statement by subtracting the mean number of statements chosen by the treatment group from the mean number of statements chosen by the control group. That number is presented in the chart below as the “indirect response.”

The indirect responses revealed significant social-desirability bias at work across all white subgroups and produced a much more dramatic spread in opinions among white respondents. Among white Americans overall, the indirect measure was nearly 20 percentage points higher than the direct measure (31 percent versus 13 percent). White non-born-again Christians and white non-southerners register the lowest indirect measures of concern, but even with these groups there is a double-digit social-desirability-bias effect at play. For example, while only 13 percent of whites outside the South say a majority-minority country bothers them, fully one-quarter register this opinion when the indirect measure is used.

Notably, the racial anxiety differences between white Republicans and white Democrats are significant on the direct question, with white Republicans more likely than white Democrats to say a majority non-white country bothers them (18 percent versus 11 percent). But this apparent difference disappears with the indirect measure; when white Democrats are given the opportunity to register this opinion indirectly, those expressing concern over racial changes jumps from 11 percent to 33 percent, while white Republicans expressing concern rises from 18 percent to 30 percent.

{snip}

[Editor’s note: In 2000, American Renaissance commissioned a similar survey on what whites think about becoming a minority. The answers are instructive.]