Black Man Kills White Man, Part I

Anastasia Katz, American Renaissance, February 11, 2022

A black man shoots a white man in the head and claims self-defense. Part One covers opening arguments and prosecution witnesses, including the woman who watched her husband die. Here is part two.

When the defense team for accused murderer Theodore Edgecomb — a black Milwaukee man who shot a white man to death — decided to claim self-defense, blacks thought they had their own Kyle Rittenhouse. If Mr. Edgecomb’s defense failed, it would be racism. An activist group called the Milwaukee Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression protested every week to support him.

At a press conference, activist Vaun Mayes said, “The question is, is self-defense reserved for certain individuals in this state? . . . Theodore Edgecomb deserves the same right that Kyle Rittenhouse got.”

Mr. Edgecomb certainly had the same right, but the two cases were not the same.

Theodore Edgecomb shot and killed Jason Cleereman on September 22, 2020. He was tried for first-degree intentional homicide, which could mean a life sentence. Jury selection began on January 20. The final 14 jurors — 12 plus two alternates — were 12 women and two men. There was only one white man. Seven jurors were “persons of color,” five of whom were black.

The defense claimed the racial breakdown of the jury wasn’t representative of the population of Milwaukee. This made no sense because blacks are 39 percent of the population and were 36 percent of the jury. Judge David Borowski kept the jury but issued an instruction at the beginning of the trial about implicit bias. Other pretrial decisions by Judge Borowski were that the term “victim” would be allowed when referring to Jason Cleereman — in the Rittenhouse case, the judge ruled that the men he killed could not be called “victims” — and that the jury would hear about Mr. Edgecomb’s record of having pleaded guilty to bail-jumping in two cases: domestic battery and drunken driving with injuries. Because of these crimes, Mr. Edgecomb had been forbidden to carry a gun.

Opening statements

The prosecutor was a white man named Grant Huebner. He told the jury that this murder began with a simple near-miss between a car and a bicycle. Victim Jason Cleereman’s wife was driving their car, and he was in the passenger seat, with the window open. A man named Theodore Edgecomb was walking his bike nearby, then got on it and started riding. Mrs. Cleereman had to swerve to avoid hitting him, and Mr. Cleereman shouted, “What the fuck?!”

Mr. Edgecomb heard him through the open window. When the couple stopped at a red light, he rode over to the passenger side of their car. A city pole camera captured Mr. Edgecomb saying something, then punching Mr. Cleereman through the open window, and riding away.

The Cleeremans followed and Mr. Edgecomb stopped his bicycle and got off. Mrs. Cleereman pulled up close to him. Mr. Cleereman got out of his car and went over to Mr. Edgecomb. Mr. Cleereman had a knife in his pocket, but nothing in his hands. The defendant pulled a handgun, raised it, and shot the victim in the face at close range. Prosecutor Huebner warned jurors during his opening that they would see video of the victim dying.

Mr. Cleereman collapsed. Without checking him, Mr. Edgecomb rode home and put the bike in his basement, where he did not usually keep it. He did not call 911. He went on the run and was missing for six months. In March 2021, a Kentucky state patrolman pulled him over, and he lied about his name. He claimed to be from the Bahamas and claimed he didn’t have a driver’s license, but the cop found the license in his car. He was arrested and extradited to Wisconsin.

“We’re going to walk you through this case,” Mr. Huebner told the jury, “A horrible senseless incident that begins with a swear word, and is escalated to a punch, and has ended with a bullet into the brain.”

Theodore Edgecomb’s lawyers were both black men, B’Ivory LaMarr, and Aneeq Ahmad. Mr. LaMarr gave the opening statement. He began by holding his hand up, with his palm facing the jury. “Do you see my hand?” he asked. “Do you see my whole hand, or do you only see the side I’m showing to you?”

He said only one side of the story was told by the government and the media, but he would now tell the jurors the other side, and he promised they would also hear from the accused. While Mr. Huebner’s opening had been all facts about the incident, Mr. LaMarr’s opening quoted Martin Luther King, and included a pep talk on the importance of jury service and “this search for justice.”

He told the jury Mr. Edgecomb was “not perfect; he makes mistakes like any other person.” One mistake was being in possession of a firearm that he “was temporarily restricted of.” Another was going on the run after killing a man in self-defense, instead of turning himself in. Mr. LaMarr admitted that his client did punch Jason Cleereman, but added that the punch “was a result of racial slurs that came from Jason Cleereman.” He said the couple had been drinking heavily, and Jason Cleereman had a blood alcohol level of .12 and THC in his system.

Mr. LaMarr told the jury that Mr. Edgecomb was not planning murder that night, even though the judge gave an instruction that the length of time a defendant spent planning a murder was not relevant. One can be guilty of murder with intent after planning the murder only “for an instant.”

Mr. LaMarr said the Cleeremans were behind a vehicle that was parallel parking, but they got impatient. He said Mrs. Cleereman drove around the car, into a lane of oncoming traffic, “coming into contact with another vehicle.” She swerved, then struck Mr. Edgecomb, who landed on top of a parked car. Mr. Cleereman hurled a “very offensive” racial slur at the fallen black cyclist.

Mr. Edgecomb got very upset, so he went over to Mr. Cleereman and said, “Are you talking to me?” Mr. Cleereman replied, “Yes, nigger, I’m talking to you.” Then Mr. Edgecomb punched Mr. Cleereman. Mr. LaMarr acknowledged that the punch was the wrong way to handle things, but after the punch, his client got back on his bike and went away. “He’s done with it.”

After that, he said, the Cleeremans “didn’t just follow Mr. Edgecomb, they chased Mr. Edgecomb.” He said Mrs. Cleereman accelerated “aggressively and violently” towards his client, and Mr. Cleereman pursued him “violently.”

The defense lawyer said the video the government would use didn’t show everything, but he would show the full video. (The video he later showed was a digitally enhanced version of the state’s video.)

Mr. LaMarr said there were five hours of “potential video,” and the government didn’t give them all five hours. The government only provided one minute and 34 seconds. Mr. Edgecomb tried to evade “violent” Mr. Cleereman for 24 seconds.

Mr. LaMarr said he would show that Mrs. Cleereman tampered with evidence and did nothing to try to save her husband’s life. He said that Stephanie Trotter, a motorist who arrived on the scene, would later testify that instead of calling 911, Mrs. Cleereman called someone named “Anna,” whose boyfriend was a police officer. He promised that Mrs. Trotter would testify that Mrs. Cleereman rifled her husband’s pockets after he was dead, and that after Mrs. Trotter told the police about this, they said only, “Thanks for the information. Have a good night.” He repeated, “Thanks for the information. Have a good night,” several times in an ominous tone.

The defense lawyer used a tape measure to show that the gun was fired from two feet away. I couldn’t tell what he was trying to prove with that.

Mr. LaMarr wrapped up by explaining that Mr. Edgecomb used the time he was on the run to find a lawyer. “He was on a quest to raise money so he could afford legal representation.”

The state’s witnesses

A white police detective named Alex Klabunde showed the jury a photo of the victim’s body covered with a yellow tarp; the victim’s foot was sticking out. He said that when he arrived on scene, there were blood stains and blood pooling. He identified a 9 mm shell casing found at the scene, and he said the medical examiner recovered some money, a set of keys, and a knife from the victim’s pockets.

He identified photos of the Cleeremans’ car, a Kia Soul. The passenger side window was mostly down. There was blood on the bit of window that stuck up from the door. There was blood on the armrest of the passenger side door. This was the result of being punched by Mr. Edgecomb.

Detective Klabunde explained that there are city-owned pole cameras on Holton Street and Brady Street, where this incident took place. Milwaukee PD kept only the relevant portions of the videos. The department keeps video considered irrelevant for only 90 days, and more than 90 days elapsed before Mr. Edgecomb was arrested in Kentucky. That is why only parts of the video were still available.

The jury watched a video showing the Cleeremans’ Kia Soul stopped at a stop light. It was dark; this incident took place shortly before 8:00 pm. Theodore Edgecomb rides up from behind on a bicycle and quickly throws a punch through the driver’s side window, and rides off. The passenger side door opens and closes.

The next pole camera video shows the cyclist turning right onto Holton Street, followed by the Kia Soul. The car pulls over, and a man, identified as the victim, Jason Cleereman, gets out of the passenger side. Mr. Cleereman walks, then runs a few steps, then falls and disappears from view.

The detective showed the jury a folding knife with a serrated blade found in the victim’s pocket. He opened the knife and estimated it was 10 inches long, with a handle of five or six inches.

The jury then saw a photo taken after the Milwaukee County medical examiner removed Mr. Cleereman’s body from the scene. There was a large pool of blood.

When Det. Klabunde was cross-examined, the defense had him show a photo of the back interior of the Cleereman’s car, implying that the photo proved the Cleeremans had been drinking alcohol. The photo showed one item that appeared to be a beverage can stuck in the rear driver’s side door, and a shoebox on the floor.

The medical examiner who performed the autopsy on Jason Cleereman was no longer working for the county, so forensic pathologist P. Douglas Kelley testified instead. He did not examine the body, so he based his testimony on the autopsy report, photographs, and investigator reports. He said the bullet was recovered from inside the victim’s head, at the back left side.

There was alcohol in the victim’s system, but he could not confirm the presence of THC. Defense lawyer Aneeq Ahmad asked the doctor to discuss gunpowder stippling — tiny abrasions from gun powder hitting the skin, which may indicate that the gun was anywhere from an inch to four feet away from the victim. The victim’s body had such stippling. Mr. Ahmad seemed to be trying to cast doubt on the distance between Mr. Cleereman and the gun. He got the doctor to say that a homicide ruling tells you nothing about whether the gun was fired in self-defense.

The state called Thomas Balistereri, a white man who owns the duplex where Mr. Edgecomb’s fiancée, Ruby Mazell lives. Mr. Balistereti, who lived in the upper-floor apartment, often saw Theodore Edgecomb there, and he said Mr. Edgecomb always kept his green GMC mountain bike in a common area between the two apartments. Mr. Balistereri was upstairs in his living room when police came to search the lower residence. They showed him a screenshot from surveillance video of a man on a bicycle, and Mr. Balistereri identified the man as Theodore Edgecomb. After searching the lower apartment, they showed him a photo of a green bicycle in his basement, in a poorly lit area crammed with storage. Mr. Balistereri told police he thought it was suspicious that the bike had been put there.

A different detective, Michael Tanem testified that he searched Theodore Edgecomb’s home. He looked for a firearm, but did not find one. He did find a loaded magazine and a pistol-cleaning kit. He also found a receipt for a 9 mm pistol of the type used to shoot Cleereman. Various items in the house had Theodore Edgecomb’s name on them.

The state’s star witness was the victim’s widow, Mrs. Evanjelina Cleereman, who is a light-skinned black woman. Her appearance must have been a surprise to the jury, after hearing opening statements from the defense that painted her husband as a racist.

Jason Cleereman with his wife and two children.

The couple had been married for 23 years and had two children. Mr. Cleereman was a lawyer, who had had a successful day at work; he wanted to go out for a drink before going home. They went to a bar, a half mile from his office. Mrs. Cleereman said she had one glass of wine and her husband had three beers. Jason asked his wife to drive home. He told her, “I’m not drunk and I don’t feel anything, but I’d rather be careful.”

A bicyclist suddenly came into Mrs. Cleereman’s lane, in front of her car, so she swerved very quickly to avoid hitting him. She said her husband shouted out the window, “What the heck?!” Then he turned to her and said, “Can you believe that?”

Shortly afterward, they stopped at a red light. The cyclist, a stranger to the Cleeremans, came up to the passenger side and stopped at the window. Mrs. Cleereman testified that he looked at her husband, and said, “Were you talking to me?”

Mr. Cleereman said, “Yes.”

Then the man punched him hard in the face. Her husband’s glasses flew past her face and fell down into the well beside her seat. She told the jury that her husband wore glasses all the time and could not see well without them. He put his hand up to his face, and said, “Where are my glasses?”

She said, “I’m trying to reach them. They’re in the well.” He looked at his fingers and said, “I’m bleeding.”

Mrs. Cleereman saw the cyclist ride off and turn the corner. She was trying to retrieve her husband’s glasses when the light turned green. Her husband said, “Just turn the corner. I want to talk to him.”

She turned right, and stopped her car when she saw the cyclist. Her husband got out of the car. He started walking toward the man on the bike. When the prosecutor asked if her husband started jogging, she said, “I don’t recall that he was running. I started driving forward.”

She pulled up because she wanted to be next to where her husband was. Although her hazard lights are on in the pole camera videos, Mrs. Cleereman didn’t remember turning them on.

Mrs. Cleereman said the cyclist rode his bike on the sidewalk a bit, then got off the bike. She said the cyclist stood and looked at her as her husband went over to him. The prosecutor asked if she remembered telling the police that her husband was going to confront him, but she said she did not remember that.

She heard no yelling or screaming from her husband nor from the cyclist; she heard no conversation at all. Mr. Huebner asked, “Did anyone, anyone use the N-word during this?” “No,” she said, adding, “He [Mr. Edgecomb] had these really dark, cold eyes. He was staring at me.”

Then she saw the cyclist pull his hand out, and there was a gun in his hand. She shouted to her husband, “He has a gun!” “My husband didn’t hear me. All I saw was this man’s eyes, and the gun, and I knew he was going to shoot my husband; I could just feel it. He pulled the trigger . . . and then he looked at me. He kept looking at me; he never took his eyes off me. And I felt like he was contemplating shooting me next.”

Her husband dropped immediately. Mr. Edgecomb stared at her. She looked to the right, and she saw someone. She looked back at Mr. Edgecomb, and he maintained eye contact. Then he turned, stepped over her husband, and walked off with his bike.

Mrs. Cleereman got out of her car and ran up to her husband. She put her hand on his back. She screamed, “Jason! Jason! Jason, are you alive?! Jason, are you OK?!”

He didn’t move, and she realized he was dead. She tried to dial 911, but she was so shaken she couldn’t dial the code to unlock her telephone. “I was struggling. I was trembling. I was trying to put my passcode in there and I couldn’t do it, so I turned to look at the people who were behind me and I think I walked up to them, or ran, I can’t remember, and I shouted, ‘Can you please call 911? I can’t do it. Can you please call 911? This man just shot and killed my husband. Please.’”

She said the bystanders hesitated, so she screamed, “Please call 911! Please call 911! Why isn’t anyone helping me?!” Then a woman began to dial her phone.

Mrs. Cleereman remembered calling her daughter and saying, “Your father’s been shot. Your father’s dead. I need you to come down here. I’m on Holton and Brady. I need you.” Her daughter said, “Mom, that’s not funny.” Mrs. Cleereman said, “I’m telling you the truth.”

Then she called a close friend, Evanna, and asked her to come. Evanna also didn’t believe the news at first, but she agreed to call others and to meet Mrs. Cleereman on Brady Street.

She went back to her dead husband. “I wanted to hug him; I wanted to pick him up. I wanted to hug him, but I couldn’t. I knew I couldn’t touch him, so I wanted something of his that I could hold on to, so I grabbed his wallet.” She took his wallet out of his pocket. Her husband was lying face down. She held onto the wallet as police were arriving. She remembered giving it to the police at some point.

The jury saw body camera footage in which Mrs. Cleereman tells the cops, “I have his wallet,” and gives it to them.

The defense made an issue of Mrs. Cleereman’s demeanor after the shooting, claiming she was too calm. Mr. LaMarr implied that Mrs. Cleereman had some responsibility for her husband’s death because she had not called 911 or tried to revive him. The prosecution played a video of her taken in the back of a squad car.

Mrs. Cleereman says to an officer, “I can’t cry. Why am I not crying?” The officer replies, “You’re probably in shock, Ma’am.” Shortly after that, she begins sobbing and wailing. In another part of the video, she tells the officer that she couldn’t call 911. He assures her it was fine, because other people called.

The prosecutor asked Mrs. Cleereman about the knife that was found in her husband’s pocket. She testified that it had not been in her husband’s hand when he approached Mr. Edgecomb. She said her husband usually used the knife as a box cutter at work. He also used the knife to cut flowers in their garden, to bring a bouquet to her.

When asked if her husband had threatened to kill Mr. Edgecomb, she said no. “My husband was not a violent man. He was a man of conflict resolution.” She never heard him threaten to kill anyone.

“You loved your husband, right?” Mr. Huebner asked. “Yes, I loved him very deeply,” she said.

The defense asked for a five-minute break to prepare for cross examination. Judge Borowksi said, “I don’t see the need for that. Why?”

Mr. Ahmad asked for a sidebar. This is a quick conference between lawyers and the judge in the courtroom, with lawyers close to the judge so they can speak softly and not be heard by the jury. The judge said the defense had asked for too many sidebars already, but he allowed the defense two minutes to print out copies of something.

There were more sidebars than usual in this trial, and relations between the black defense lawyers and the white judge were bad. “Black Twitter” accused the judge of being biased, but other people watching the trial on Court TV noted how clumsy the defense was.

[LIKE A DOG] [TOTALLY BIASED] [KMART EDITION]

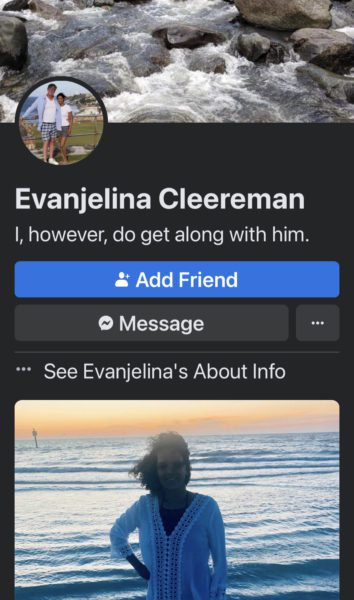

The jury was asked to leave the courtroom, and the defense tried to introduce printouts of the Cleeremans’ Facebook profile pages. Jason Cleereman’s profile had the tagline, “We probably won’t get along.” His profile picture was a screaming gorilla.

Evanjelina Cleereman’s profile had the tagline, “I, however, do get along with him.”

The prosecution objected to these as irrelevant. Mr. LaMarr said the widow opened the door to this evidence by talking about “the peacefulness” of her husband, and the profiles would show otherwise.

Judge Borowski shouted, “These Facebook posts don’t show anything! First of all, Counselor, start by identifying them.” Mr. LaMarr said they were screenshots, and the judge asked who got the screenshots. Mr. LaMarr said they were publicly available online. The judge repeated, “Tell me who got the screenshots.”

“We got the screenshots,” Mr. Lamarr answered. “The paralegal, Ashley, just printed them out.” The judge ordered that Ashley stay out of the courtroom for the rest of the trial, because at that point, she was considered a witness in the case. Mr. Ahmad said they never intended to call her. “She just assists us in collecting certain things like news articles, videos, things like that.” Judge Borowski said, “For situations like that, you should use an investigator, not an employee of your office.”

The defense explained again that it wanted to use the Facebook screens to counter Mrs. Cleereman’s claim that her husband was a conflict resolver. Mr. Huebner argued that the quote, “We might not get along,” said nothing about Mr. Cleereman’s character. “There are plenty of people that I don’t get along with,” Mr. Huebner said, “that have never punched me or shot me in the face.”

The judge denied admission of these documents, saying, “Facebook is part of the downfall of society.” The jury and the widow were brought back in.

During cross-examination, Mr. LaMarr played a snippet of video of Mrs. Cleereman in the back of a police car, asking the officer about her husband, “He’s OK, right?”

Mr. LaMarr used this to attack her credibility, because she had earlier said she checked to see if he was alive. Mrs. Cleereman insisted that she did check and she knew he was dead. She said his hands were purple, he felt cold, and there was a pool of blood. She told Mr. LaMarr that she was in shock.

On redirect, Mr. Huebner played the full video, which showed the widow holding her hands to her face and wailing, “No one’s going to love me like you loved me, my love!” then suddenly leaning forward to ask, “He’s OK, right?” The full video made it clear that this was a moment of denial from a wife overcome with grief. She told the court, “I was hoping it was a bad dream.”

The defense asked her why she took her husband’s wallet, and what was in it. She said the wallet contained IDs and credit cards. Mr. LaMarr asked if having the credit cards was important to her, and she said it was not about the contents, but just about having something of her husband’s to hold on to.

Mr. LaMarr asked Mrs. Cleereman about her testimony that her husband shouted, “What the heck?” He pointed out that in a media interview after the event, she told the press that her husband had said, “Hey, what’s the problem?” Mrs. Cleereman said she didn’t remember telling the interviewer that. The defense never played the interview for the jury.

It did play police video of Mrs. Cleereman on the phone, telling her sister what happened. In the video, Mrs. Cleerman says that her husband had said, “What the fuck?” Mrs. Cleereman said that she uses swear words herself, but she still remembered her husband’s words were “What the heck?”

The defense talked about the Cleeremans’ drinking that night. Mr. Cleereman’s blood alcohol level was .12, over the legal limit of .08. Mrs. Cleereman said that her husband had drunk four beers at most. When the defense asked if Mr. Cleereman used marijuana, Mr. Huebner objected, but the judge overruled. Judge Borowski was often irritated with the defense, but did not always rule against it.

Mrs. Cleereman said her husband used marijuana once in a while for neck pain, but she did not see him use any that day.

Mr. LaMarr asked Mrs. Cleereman if her car touched Mr. Edgecomb. She said no. She swerved around him and she could see in her rearview mirror that he was still on his bike. She said emphatically, “He did not fall off his bike.”

Edgecomb with his bicycle. Still from surveillance video.

The defense showed the city pole-camera video, in which Jason Cleereman gets out of his car, and approaches Mr. Edgecomb, walking at first and then jogging. Mrs. Cleereman said she did not see her husband “chasing” Mr. Edgecomb; she saw her husband walk up to him. Mr. LaMarr then impeached her by playing a police video of her saying to a police officer, “My husband got out of the car, turned the corner and chased him.”

The state called Sergeant Tyler Kirkvold, of the Milwaukee PD. He testified that he collected video from cameras on the street. He was the one who decided which parts to keep. Mr. LaMarr asked the officer if he knew where “the first incident” — in which Mr. Edgecomb was hit by a car and knocked off his bike — occurred. Sgt. Kirkvold did not.

Mr. LaMarr asked what the police had done to find out where that happened. The sergeant said they tried to find video from farther east on Brady, the road where it would have happened. Mr. LaMarr asked if he ever took Mrs. Cleereman in a car to ask her where the first incident occurred. The sergeant never did that, nor did any other officer.

Mr. LaMarr asked if police try to make sure evidence is not moved or removed, and the officer said yes. Then Mr. LaMarr asked if he inquired why Mrs. Cleereman took a wallet from the victim’s body. “I don’t believe I did,” the sergeant said.

Mr. LaMarr began asking whether something could have been moved from one place to another at the scene, and the state objected: “There’s absolutely no evidence that anything was moved.” The judge agreed. “That’s right; there’s no evidence of that. Don’t imply something, Counselor, that there’s no evidence of. None! Move on to a relevant question.”

Mr. LaMarr asked about the knife in Mr. Cleereman’s pocket. “You don’t know who all touched that knife on September 22, 2020, do you?” The sergeant said that he did not know if anyone went into Mr. Cleereman’s pocket before the medical examiner removed the knife. “In fact, there was no DNA taken off that knife,” LaMarr said. The sergeant didn’t know.

On redirect, Mr. Huebner asked if there was any evidence of anyone having gone through Mr. Cleereman’s pockets before the medical examiner did. The only evidence was the fact that Mrs. Cleereman had taken the wallet. The sergeant testified that Cleereman was found face down at the crime scene. Someone would have had to move the body to get something from the front pocket to get the knife.

The State called Detective Rudolfo Alavardo, who interviewed Mrs. Cleereman at the scene, and corroborated her testimony. Under cross, Mr. LaMarr pressed him hard on why he didn’t take Mrs. Edgecomb in a squad car, to find the exact location where she had swerved her car, trying to avoid the bicycle. During an objection from the State, Judge Borowski commented that Mr. LaMarr was trying to imply that the police officers were not doing their job, but if Mr. Edgecomb had not run away, he could have told the police what happened.

Officer Richard Ellis, a Kentucky state policeman, testified that when he stopped Mr. Edgecomb, the defendant claimed his name was “Agoo Newman,” and that his driver’s license was at home — in the Bahamas. He also lied about his birthdate, and claimed he started his trip in Texas, not Wisconsin. Officer Ellis searched the car and found Theodore Edgecomb’s driver’s license. A police check turned up active warrants for bail-jumping and murder. The defense asked Officer Ellis if Mr. Edgecomb had been cooperative. “To an extent,” the officer said, referring to the lies. The officer added that Mr. Edgecomb did not resist arrest.

The next witness was Jeffrey Parr, who witnessed the shooting. He was working in a nearby café and was standing outside, smoking on his break. He saw a car following a bicycle, with a lot of space between. The car swerved towards the bicyclist, and a passenger got out. The cyclist got off his bike. Mr. Parr said the passenger walked toward the bicyclist, who was just standing there. He heard no conversation between the two men. Although he didn’t see a gun, he saw the bicyclist raise his hand and he heard a gunshot. The passenger fell face forward. The bicyclist took off. Mr. Parr went inside and called 911, reporting that he saw a man get shot in the face. When the 911 operator asked if the victim was moving, Mr. Parr said no.

Jose Perez also saw the shooting. The prosecutor asked if he had seen a weapon or any other object in the victim’s hands before he was shot, and Mr. Perez said, “No.”

On cross, video of the incident was played, and Mr. LaMarr pointed out that the Cleeremans’ car had made an illegal right turn from the middle lane instead of the right lane.

Rodtrell Cameron, a black man, did not want to testify in this trial, but he was compelled to as a material state’s witness. He came in wearing orange prison clothes and appeared to be handcuffed. There were no deals or negotiations to get him to testify.

Mr. Cameron told the court that when he was stopped at a red light, a man on a bike rode up past him and stopped at the car in front. He saw the rider punch the man in the passenger seat and Mr. Cameron exclaimed aloud, “Oh, shit!” He could not hear any of the words exchanged between the man on the bicycle and the passenger.

He saw the bike turn right and go up Holton, and saw the car go after the bike. Mr. Cameron followed behind the car to see what would happen.

“The guy was pretty much forced off the street by the car, because he fell off his bike trying to get up the curb,” Mr. Cameron said. “He proceeded to run . . . . And that’s when the guy in the passenger seat gets out of the car and proceeded to run after the guy.”

He said Mr. Cleereman “forced him into a corner” and put both fists up. He did not see anything in Mr. Cleereman’s hands. He saw Mr. Edgecomb pull a gun and shoot Mr. Cleereman in the head, and saw Mr. Cleereman “fall right down on the ground.” The shooter hesitated a moment before moving away.

Mr. Cameron called 911, then stayed and waited for the ambulance. He walked up to the body. The victim was lying chest down, but his head was turned and Mr. Cameron could see his face. He could see only one of the dead man’s hands, and the hand was bloody.

He saw that the driver of the victim’s car was on the phone; she asked Mr. Cameron if he called the police. When he said yes, she continued her conversation, saying, “Your brother is dead.”

Mr. Cameron overheard Mrs. Cleereman saying that a guy was riding the wrong way in the bike lane and she nearly hit him. He heard her say that her husband had told the cyclist to “Get the F out of the way,” and then the cyclist came up to the car and asked, “Are you talking to me?” When her husband said yes, that’s when the cyclist punched him in the face.

Mr. Cameron thought the woman on the phone was surprisingly calm. “I was hysterical,” he said. “I had just seen a man who got his head blown off. She was calm.”

Mr. Cameron’s call to 911 was played. He urgently repeated the intersection where the shooting took place: “Brady and Holton! Brady and Holton! He got shot in the head!”

“A guy, he was on a bike, he rode up to the car in front of me and punched a guy in the face. The guy rode behind him, and tried to approach the guy on the bike, he jumped out of the car, and then squaded up, and he turned around and just shot him.” Mr. Cameron explained that “squaded up” means to get in a boxing stance.

He described the shooter and the bicycle and urged 911 to send someone. “You need to get in the area. The guy can’t be too far. . . . He on his bike. He shot right in the head. I can’t believe that.”

Mr. Cameron stayed and talked to police when they arrived. He remembered telling the police that he “would have just fought,” meaning a fist fight. Mr. Cameron agreed with Mr. Huebner that, although the victim “squaded up,” he never took a swing at Mr. Edgecomb before being shot.

During cross, Mr. LaMarr asked if he saw a vehicle swerve, but Mr. Cameron said he did not see anything that led up to the punch, and Mr. Edgecomb did not brandish a firearm when he went up the car.

He said Mr. Edgecomb looked a bit shocked and surprised after he fired his gun. On redirect, Mr. Huebner asked if in his phone call to 911 he called the shooting “cold blooded.” “The shot was cold-blooded,” Mr. Cameron replied.

The state made an excellent case, but would the defense convince the jury it was self-defense? The shooter himself was to take the stand.