Gloom, Despair and Agony

Stephen Webster, American Renaissance, February 2010

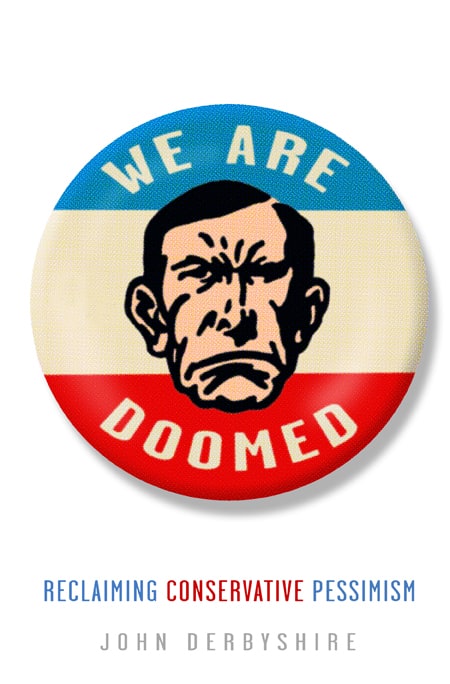

John Derbyshire, We Are Doomed: Reclaiming Conservative Pessimism, Crown Forum, 2009, 272 pp.

John Derbyshire is one of the few grown ups still writing for National Review, and his articles, blog postings and “Radio Derb” podcasts are about the only reason to visit National Review Online (NRO). He is an engaging writer with an interest in many things — politics, mathematics, science, poetry, and history — and has the breadth of knowledge and experience to write about them with a politically-incorrect forthrightness that makes one wonder how he manages to survive among the Buckleyites. We Are Doomed considers the prospects for the modern conservative movement, and as the title suggests, it is not optimistic.

Back in 2004, when it was clear to all observers outside of the White House that George W. Bush’s Iraq strategy wasn’t working, an unidentified senior presidential aide explained to New York Times reporter Ron Suskind that the “reality-based community” was outmoded and that it was a mistake to “believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality.” The aide went on:

That’s not the way the world really works anymore. We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality — judiciously, as you will — we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors . . . and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.

What that statement illustrates — aside from the astonishing arrogance of the Bush administration — is what Mr. Derbyshire identifies in We Are Doomed as the central failing of the modern conservative movement: its inability to accept reality, whether in foreign policy, education, immigration, or for that matter, nearly any other aspect of society. Conservatism, he writes, “has been fatally weakened by yielding to infantile temptations: temptations to optimism, to wishful thinking, to happy talk, to cheerily preposterous theories about human beings and the human world.”

As a result, conservatism cannot give society the dose of cold, hard reality it needs to deliver itself from these temptations. Thus we foolishly try to democratize the Middle East, bring in uneducated Somalis and expect them to become productive citizens, and assume that all inner-city blacks could go to Harvard if only we shoveled enough money at them. A true conservative, Mr. Derbyshire argues, is by nature pessimistic. He understands the fallen nature of mankind, and ought to pour cold water on any attempts at mass uplift. That conservatives do not do this shows only how successful the liberals have been at getting them to swallow and internalize their agenda.

Needless to say, the vast majority of Americans who call them “conservatives” are abusing the language. As the late Sam Francis used to point out, anyone who isn’t even interested in conserving his own racial stock is a freak, and certainly not a conservative. And when so-called conservatives adopt the Left’s puerile optimism about revamping human nature and transforming the world, they are not so much conservatives as dupes.

It has not always been this way. Mr. Derbyshire reminds us that America’s Founding Fathers were a pessimistic lot, given their Calvinist religion and the unforgiving nature of life in the early colonies, where death — whether from disease, childbirth, accident, or Indian — was a constant companion. If the early settlers were inclined to forget this, “there were always bears, wolves, and crop failures to remind them of the biological facts.” As America grew, and the frontier advanced beyond the Eastern seaboard, the “optimistic rot” began to set in. Calvinism gave way to Unitarianism, which paved the way for Transcendentalism, which led to the birth of “the modern style of vaporous happy talk.” Mr. Derbyshire observes that the reformers abolished slavery, improved the social condition of women, reduced “promiscuous drunkenness” and some other things, but over time, these blessings turned into blights.

Improving the lot of workers led to “featherbedding, the Teamster rackets, auto companies made uncompetitive by extravagant benefits agreements, and government unions voting themselves ever-bigger shares of the fisc. The campaign for full civil rights and racial justice turned into affirmative action, race quotas, grievance lawsuits, the Reverend Jeremiah Wright, and everlasting racial rancor.” As early as Prohibition, it was clear that progressives were at war with human nature itself, a war that continues to this day.

There are many fronts in the war against human nature, and the bulk of We Are Doomed is spent surveying them. First up is diversity, which, Mr. Derbyshire writes, is nothing to celebrate. Much of what he cites, from the work of Harvard professor Robert Putnam to individual examples of racial conflict are familiar to AR readers (see, for example, “Diversity Destroys Trust” in the September 2007 issue), but he does have an entertaining spin. He regards diversity as a cult and a false ideology, and notes that the “downside of ethnic diversity will keep cropping up throughout my book” (it does). Mr. Derbyshire understands the diversity mindset quite well, and boils it down to its essence as follows:

Different populations, of different races, customs, religions, and preferences, can be mixed together in any numbers or proportions at all, with harmonious results. Not only will the results be harmonious, they will be beneficial to all the people thus mixed. They will be better and happier than if they had been left to stagnate in dull homogeneity.

This is hogwash, of course, but there are people who believe it. Mr. Derbyshire refers to them — the lawyers, educators, corporate and government bureaucrats who make their livings shilling for diversity — as “Diversicrats,” and fears that they will never give up. He is dismayed that so many first-rate minds, like Prof. Putnam’s, have been corroded by an ideology that is “demonstrably — easily demonstrably — false” and is particularly disappointed that so many conservatives, who should know better, have embraced it. By doing so, they “have surrendered key political positions: equal treatment under the law, allegiance to one nation, freedom of association, public education in one language . . .” Had conservatives not given in to the Diversicrats, “we might have maintained the principles of a free republic, and saved ourselves much trouble and expense.”

Mr. Derbyshire is equally disgusted with politics — “We have . . . lost our republican virtue, traded it in for a passel of gassy rhetoric” — and modern culture — “It’s not so much the filth aspect of pop culture as the impression that there’s nothing there.”

Mr. Derbyshire cites the poetry of Elizabeth Alexander, who performed at Barack Obama’s inauguration. “I had never heard of this lady before the president-elect tapped her for the inauguration spot,” he writes. “Taking a wild shot in the dark, I guessed her to be a whiny black feminist, as most female poets are nowadays.” After providing examples of her work, he writes, “You could sum up her thematic range as ‘I’m black! Black black black! And I have a vagina!” He laments the feminization of society, and even questions the wisdom of women’s suffrage, noting that “women incline to socialism much more naturally than men.”

Of education, Mr. Derbyshire writes, “There is no area of social policy where we see more clearly the destructive effects of the modern epidemic of happy talk, no area where the magical thinking of our intellectual cheerleaders is so clearly, painfully at odds with cold grim facts.” He goes on to provide grim fact after grim fact demonstrating that the people running the “edbiz” don’t have a clue about how to educate children — “From false premises they proceed to false conclusions” — but notes that nothing is likely to change, given the powerful influence of the teachers unions over both political parties.

The racial achievement gap, the behavior gap, the math gap between boys and girls — closing all of these gaps is the single most important goal for educationists. It is where all the money and effort goes, and explains why honors and gifted programs have to be cut back. What do the uplift artists have to show for all this? Nothing, but they persist in trying to find a way to close the gaps because they cannot admit they are biological and cannot be closed. Education therefore becomes “a vast sea of lies, waste, corruption, crackpot theorizing, and careerist logrolling.”

Arguably the most important chapter in the book is on human nature, in which Mr. Derbyshire provides a concise summary of the state of the nature vs. nurture debate, although he prefers the terms Culturist and Biologian. Anyone who has even a passing familiarity with the science knows that the Biologians have the upper hand — decisively so. To the extent that the general public does not understand this it is testimony to the power held by the Culturists — who include most of the media and educators. Conservatives are largely AWOL in this debate, because many of them adhere to a belief Mr. Derbyshire calls Religionist. The Religionists do not accept the science of the Biologians, which makes them easy prey for Culturist, diversity-friendly propaganda. Again, for most AR readers, this is settled territory.

Race realists will also be familiar with many of the arguments in the chapter on immigration. Mr. Derbyshire has little patience for sentimentalism in any aspect of public policy, and none at all when it comes to immigration — which as he reminds us, is simply another national policy, like farm supports or national parks maintenance. It should be based on the national interest, not on nostalgia or some hazy moral imperative. Mr. Derbyshire deplores what he calls the hypermoralization of immigration, and considers the complicity of “cheerily optimistic conservatives” in this as “perhaps their greatest sin against good sense and proper conservative skepticism.” “Romantic moralizing,” he adds, “belongs on the political Left.”

The problem with too many of today’s immigrants is not just that they are not assimilating, but that they are actually absimilating, that is, moving further away from mainstream American society. This is especially true of Mexican immigrants — second and later generations do worse than their parents — and of second-generation Muslims, who are far more likely than their parents to go radical. And yet to point out this or any other problem with immigrants leads to accusations of nativism and racism, often at the hands of conservatives, too many of whom, Mr. Derbyshire writes, “have been cheerleaders for a vast experiment in social engineering.” He continues:

Rather than carefully project the results of the experiment, they simply declare those results to be inevitably good, on no grounds at all but their own vapid optimism and wishful thinking. Aren’t conservatives supposed to be hostile to social engineering schemes? Why do so many conservatives swoon with approval at this one, while snarling at immigration skeptics as heartless xenophobes? The question is rhetorical. I have no idea what makes people so stupid and dishonest.

Mr. Derbyshire is similarly contemptuous of conservatives who promote international crusades to spread democracy and engage in nation building, naively asserting that American exceptionalism will somehow protect us from the consequences of bad policies, and who use their positions in government and business to squander American wealth and to bury our children and grandchildren under a mountain of debt.

Normally in a work that paints a bleak picture, the author tries to end on a positive note, offering a ten-point plan that will turn things around. Not this time. Mr. Derbyshire is firm: We are doomed, and the best we can hope for, “if we approach the universe more realistically — pessimistically” is better preparation for the nasty consequences nature is sure to throw at us. He also allows for the possibility — the very slight possibility — that the happy-talk scales will fall from the eyes of conservatives, but he’s clearly not betting on it.

We Are Doomed, despite its serious subject matter, is an entertaining, even witty book. It wouldn’t be accurate to describe it as light reading, but it is more a work of Internet-era opinion journalism than of scholarship. There are no footnotes or index. Still, it is refreshing to read a mainstream author who is not only undeceived about race, but willing — even eager — to talk about it in a way that verges on race realism.

Overall, however, race realists will find little that is new in We Are Doomed. Most are already pessimistic, and have long since given up on the mainstream Right. Most likely to profit from this book are conservatives who are beginning to lose faith, who are starting to doubt that diversity is a strength, are tired of pushing one for English, who wonder why the newspapers don’t print the races of criminal suspects, and are starting to notice the correlation between good schools and white neighborhoods.