1.5 Million Missing Black Men

Justin Wolfers et al., New York Times, April 20, 2015

In New York, almost 120,000 black men between the ages of 25 and 54 are missing from everyday life. In Chicago, 45,000 are, and more than 30,000 are missing in Philadelphia. Across the South–from North Charleston, S.C., through Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi and up into Ferguson, Mo.–hundreds of thousands more are missing.

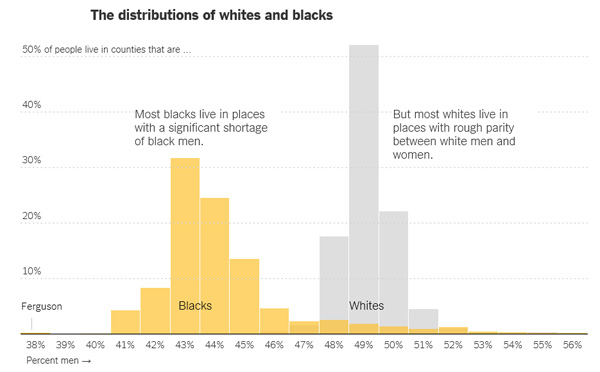

They are missing, largely because of early deaths or because they are behind bars. Remarkably, black women who are 25 to 54 and not in jail outnumber black men in that category by 1.5 million, according to an Upshot analysis. For every 100 black women in this age group living outside of jail, there are only 83 black men. Among whites, the equivalent number is 99, nearly parity.

African-American men have long been more likely to be locked up and more likely to die young, but the scale of the combined toll is nonetheless jarring. It is a measure of the deep disparities that continue to afflict black men–disparities being debated after a recent spate of killings by the police–and the gender gap is itself a further cause of social ills, leaving many communities without enough men to be fathers and husbands.

Perhaps the starkest description of the situation is this: More than one out of every six black men who today should be between 25 and 54 years old have disappeared from daily life.

{snip}

Incarceration and early deaths are the overwhelming drivers of the gap. Of the 1.5 million missing black men from 25 to 54–which demographers call the prime-age years–higher imprisonment rates account for almost 600,000. Almost 1 in 12 black men in this age group are behind bars, compared with 1 in 60 nonblack men in the age group, 1 in 200 black women and 1 in 500 nonblack women.

Higher mortality is the other main cause. About 900,000 fewer prime-age black men than women live in the United States, according to the census. It’s impossible to know precisely how much of the difference is the result of mortality, but it appears to account for a big part. Homicide, the leading cause of death for young African-American men, plays a large role, and they also die from heart disease, respiratory disease and accidents more often than other demographic groups, including black women.

{snip}

The gender gap does not exist in childhood: There are roughly as many African-American boys as girls. But an imbalance begins to appear among teenagers, continues to widen through the 20s and peaks in the 30s. It persists through adulthood.

{snip}

The black women left behind find that potential partners of the same race are scarce, while men, who face an abundant supply of potential mates, don’t need to compete as hard to find one. As a result, Mr. Charles said, “men seem less likely to commit to romantic relationships, or to work hard to maintain them.”

The imbalance has also forced women to rely on themselves–often alone–to support a household. In those states hit hardest by the high incarceration rates, African-American women have become more likely to work and more likely to pursue their education further than they are elsewhere.

{snip}

It does appear as if the number of missing black men is on the cusp of declining, albeit slowly. Death rates are continuing to fall, while the number of people in prisons–although still vastly higher than in other countries–has also fallen slightly over the last five years.

{snip}