What Really Happened?

AR Staff, American Renaissance, January 2003

A conviction that we should be ashamed about the treatment of Japanese-Americans during World War II is part of the conventional wisdom of our time. Columnist Myriam Marquez wrote recently in an entirely typical op-ed piece of the “injustices” and the “abominations” of the “internment camps for Americans of Japanese descent during World War II.” [1] Americans believe with an almost religious conviction that their country committed a heinous act, and many take pride in denouncing the actions of their fathers and grandfathers.

What actually happened, and why? Before entering into details, here is an outline of the facts: As a war-time measure, the federal government required all Japanese-Americans to evacuate a large part of the American Pacific coast. They were free to move from the exclusion zone on their own, and to resettle anywhere else in the United States. Those who did not were taken first to assembly centers and then to ten relocation centers built for them as far east as Arkansas. They could stay in the centers if they wished or they could take jobs or attend college anywhere in the United States except the West Coast.

The centers were therefore not internment camps, but living facilities offered by the government to those who were forbidden to live in the exclusion area and who did not make other arrangements. The centers, though built in the same austere style as American Army barracks, had many amenities and were run by Japanese-Americans. By the end of 1944, with eight months of war still to go, several thousand people had already left the camps to find homes and jobs in the central and eastern United States. The US Army was careful to look after the evacuees’ property, and Congress appropriated several million dollars soon after the war to compensate Japanese-Americans for losses that did occur.

Were there any forcible internments? Immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Department of Justice incarcerated about 3,000 Japanese aliens who had been on a “danger” list since 1939. [2] There were also some Japanese-Americans in the relocation centers who openly supported Japan in the war. They and their families (since no families were split), were sent to a real internment camp behind barbed wire, where for the duration of the war they paraded with rising-sun armbands and celebrated December 7 as a holiday. The government actually locked up only a small minority of Japanese-Americans — those who posed a genuine war-time security risk.

The Sequence of Events

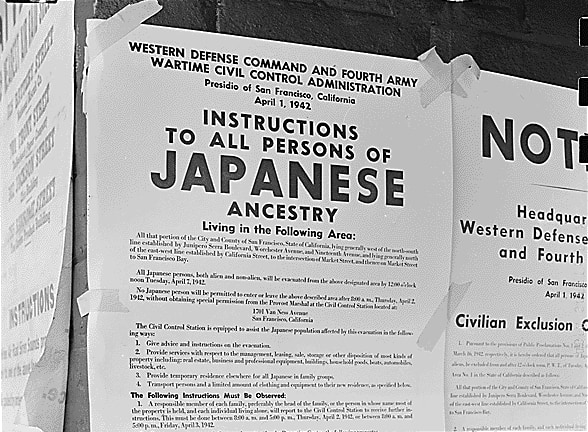

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the establishment of military exclusion areas. The next month, Lt. General John L. DeWitt declared a major portion of the West Coast (approximately the western halves of Washington, Oregon and California, and the southern third of Arizona) a military area from which all people of Japanese descent would have to move. There was no effect on Japanese-Americans living elsewhere, other than that they could not go to the West Coast. The evacuation was put in the hands of Col. Karl R. Bendetsen, and Roosevelt created the War Relocation Authority (WRA) under the direction of Milton Eisenhower, brother of Dwight Eisenhower, to help the evacuees. Congress voted to approve the relocation, and the US Supreme Court considered and upheld relocation no fewer than three times. [3] Civil liberties groups were silent or supported evacuation, and there was no opposition in Congress. [4]

For a short time, the plan was to help the Japanese-Americans move inland on their own. Col. Bendetsen, who managed the evacuation, later testified that “funds were provided for them [and] we informed them . . . where there were safe motels in which they could stay overnight.” [5] Most families were not able to move quickly, however, and governors of states east of the exclusion zone complained about the prospect of thousands of people of Japanese descent moving into their states without oversight. [6]

Accordingly, by late March the relocation effort entered the “assembly center” phase. Japanese-Americans were moved into improvised centers on the West Coast until ten more-permanent relocation centers could be built further east in Arizona, Arkansas, eastern California, Colorado, Idaho, Utah and Wyoming. The evacuees could choose either to live in an assembly center or move east on their own. [7] Public apprehension lessened over time, partly due to calming efforts by federal officials, and during the assembly center phase, some 4,000 families moved inland “on their own recognizance” with WRA help. [8]

The temporary centers were rudimentary, but the government and the Japanese-Americans made them as pleasant as possible. They were run almost entirely by the occupants. With WRA support, the centers quickly set up libraries, Boy Scout troops, arts and crafts classes, musical groups, film programs, basketball and baseball leagues, playgrounds, calisthenics classes, and even in one case a pitch-and-putt golf course. Because the occupants did not have jobs (or regular expenses for that matter), men and women were able to devote considerable energy to camp activities.

The assembly center phase was over by the end of summer, 1942, with all Japanese-Americans moved to the more-substantial relocation centers as soon as they were constructed. By November 1, 1942, the relocation centers housed what was to be their largest population: 106,770. [9]

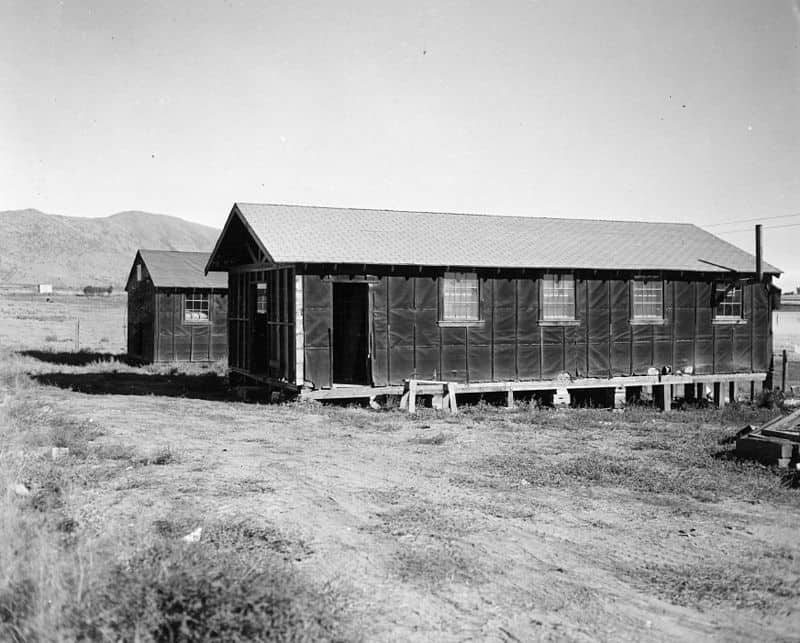

The relocation centers were built in the same way as housing for American soldiers overseas. Scholar, university president, and eventual United States Senator S.I. Hayakawa wrote extensively about the centers but was never in one, having spent the war years teaching at Illinois Institute of Technology. He called the centers “dreary places,” but they rapidly became livable communities with many amenities: stores, theaters, hairdressers, newspapers, ping-pong, judo, boxing, badminton, sumo wrestling, basketball and baseball leagues, gardens, softball diamonds, tennis courts, hiking trails, classes in calligraphy and other subjects, art competitions, libraries with Japanese-language sections, and worship facilities (for any religion except Shinto, which involved emperor-worship).

Housing in a Japanese relocation camp.

The centers had accredited schools from kindergarten to high school, with music classes, school choruses, achievement testing, high school newspapers and annuals, dances, PTA meetings, student councils and class officers. The University of Utah lent caps and gowns for high school graduation at the Topaz center. [10] The education programs were designed to encourage assimilation, a process criticized by multiculturalists today as a form of “racism.” [11] The WRA had veto power, but otherwise the internal operation of the camps, like that of the assembly centers, was in the hands of evacuees, who elected their own representatives. [12]

As their name suggests, the relocation centers were camps from which Japanese-Americans could disperse throughout the United States, other than to the West Coast, and S.I. Hayakawa wrote that about half chose to do that. [13] (David D. Lowman, a war-time intelligence officer who has written about the internments, sets the figure slightly lower at “about 30,000.” [14])

Hayakawa tells us that by September 1942 “hundreds of Issei [first-generation immigrant] railroad workers were restored to their jobs in eastern Oregon.” [15] The WRA operated field offices in cities in the mid-west and east to find jobs for anyone who wanted to leave. Churches maintained hostels in four cities for job-seekers. [16] The government even appropriated four million dollars to help evacuees start businesses away from the centers. Many, particularly those who had worked in agriculture, left the camps to do seasonal farm work. Five thousand left the centers to harvest sugar beets in various western states. [17]

College-age young people attended university during the war. Two hundred and fifty were already attending 143 colleges by the fall semester of 1942, just nine months after Pearl Harbor. Eventually, 4,300 attended 300 different universities. [18] Some won scholarships, and a “relocation council” funded by foundations and churches helped with college expenses. [19]

In early 1944 — with a year and a half of war still remaining — the government began to let those who had passed security investigations return to the West Coast. The exclusion order was ended for all Japanese-Americans on January 2, 1945, well before V-J Day in August. Except for the internment camp at Tule Lake, all the centers were closed by December 1, 1945. [20]

Tule Lake held three kinds of people: Those who had applied to be repatriated to Japan, those who had answered “no” to a loyalty questionnaire and had not been cleared by further investigation, and those for whom the government had evidence of disloyalty. [21]

Concentration Camps?

It is common to write of the relocation centers as if they were concentration camps. One author evokes the “parallel experience of the German Jews,” and it is common to speak of the centers as “concentration camps,” as if they were no different from Dachau or Buchenwald. [22] Critics often refer to “barbed wire and armed guards.” If the relocation centers actually had these it would certainly suggest forcible incarceration. This is therefore an important factual question, and Col. Bendetsen was adamant during Congressional hearings in 1984 that there were no watchtowers or barbed wire: “That is 100 percent false. . . . Because of the actions of outraged U.S. citizens [after the Pearl Harbor attack], of which I do not approve, it was necessary in some of the assembly centers, particularly Santa Anita, . . . to protect the evacuees . . . and that is the only place where guards were used.” As to “relocation centers . . . there was not a guard at all at any of them. That would not be true of Tule Lake” [which had guards after it became an internment center]. [23]

Japanese relocation center barracks.

Three years earlier, Col. Bendetsen had given similar testimony before the highly partisan commission that eventually recommended paying reparations to the evacuees. During those hearings, Senator Edward Brooke asked about the conflict between his account and those of others. He replied: “A great part of the testimony was given by people who were not yet born then. . . . You had testimony available from many people who were not given an opportunity to present it, some of whom were physically intimidated by the people who were in attendance day after day. . . . I have received a barrage of mail. . . . There were many people who in good faith wanted to testify that they thought the conditions were nowhere close to some of the testimony [claiming there was internment] you have heard.” [24] Neither in 1981 nor in 1984 did any of Col. Bendetsen’s questioners contradict his testimony or offer to produce evidence that he was mistaken.

There are many books about the centers that include photographs of fences and watchtowers, but they rarely explain where the pictures were taken or when. What are offered implicitly as photos of scenes common to all the relocation centers may well be pictures of Tule Lake.

There have been equally tendentious claims about theft or destruction of evacuees’ property. No doubt some Japanese-Americans suffered at the hands of unscrupulous opportunists in early 1942. However, the army took great care to protect property. As Col. Bendetsen testified:

“When you are told that the household goods of the evacuees after I took over were dissipated, that is totally false. The truth is that all of the household goods of those who were evacuated or who left voluntarily were indexed, stored, and warehouse receipts were given. And those who settled in the interior on their own told us, and we shipped it to them free of charge. As far as their crops were concerned, the allegations are totally false. I used the Agriculture Department to arrange harvesting after they left and to sell the crops at auction, and the Federal Reserve System, at my request, handled the proceeds. The proceeds were carefully deposited in their bank accounts in the West to each individual owner. And many of these farms were farmed the whole time — not sold at bargain prices, but leased — and the proceeds were based on the market value of the harvest.” [25]

Losses that occurred despite this effort were compensated by means of the “Claims Act” enacted by Congress in 1948. Evacuees received a total of $38 million for property losses.

Reasons for Relocation

What were the military reasons for the exclusion order? The destruction of the American fleet at Pearl Harbor left the West Coast of the United States open to attack. A Japanese submarine shelled a California oil refinery on February 23, 1942, and Los Angeles imposed a blackout two days later when five unidentified planes appeared in the sky. Draftees hurried to make up for the country’s lack of preparation, even training with wooden guns Louisiana. [26]

In late 1941 and early 1942, the Japanese swept across Asia, attacking Hong Kong, Malaysia, the Philippines, Wake and Midway islands, Thailand, Guam and Singapore. In February 1942, the Japanese won a brilliant naval victory in the Battle of the Java Sea. The Japanese advance seemed unstoppable.

It is ludicrous to argue that there was no military justification for the relocation. Local officials worried about the vulnerability of the water supply and of large-scale irrigation systems, which were impossible to guard. Anyone who knows anything about California’s frequent brush fires understands why officials feared a possible “systematic campaign of incendiarism,” especially during the dry season between May and October. Earl Warren, who was then Attorney General of California and later became Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court, produced maps showing that the Japanese-American population was concentrated near shipyards and other vital installations. [27]

At the same time, it was clear from decoded Japanese government messages that Japanese-Americans were spying for Japan. The US Navy had broken the Japanese diplomatic code in 1938, and decoded messages classified “higher than Top Secret,” went under the code name MAGIC to a handful of people at the very top of the Roosevelt administration.

Intelligence officer David Lowman testified in 1984 about Japanese espionage: “Included among the diplomatic communications were hundreds of reports dealing with espionage activities in the United States and its possessions. . . . In recruiting Japanese second-generation and resident nationals, Tokyo warned to use the utmost caution.” In April 1941, “Tokyo instructed all the consulates to wire home lists of first — and second-generation Japanese. . . .” The next month, “Japanese consulates on the west coast reported to Tokyo that first — and second-generation Japanese had been successfully recruited and were now spying on shipments of airplanes and war material in the San Diego and San Pedro areas. They were reporting on activities within aircraft plants in Seattle and Los Angeles. Local Japanese . . . were reporting on shipping activities at the Bremerton Naval Yard [near Seattle]. . . . The Los Angeles consulate reported: ‘We shall maintain connections with our second generation who are at present in the Army to keep us informed’. . . . Seattle followed with a similar dispatch.” [28]

On January 25, 1942, the Secretary of War informed the Attorney General that “a few days ago it was reported by military observers on the Pacific coast that not a single ship had sailed from our Pacific ports without being subsequently attacked.” [29] Was it unreasonable to assume that spies were at work?

Three days before Pearl Harbor, the Office of Naval Intelligence had reported a Japanese “intelligence machine geared for war, in operation, and utilizing west coast Japanese” (emphasis added). Intelligence officer Lowman testified in 1984 that on January 21, 1942, an Army Intelligence bulletin “stated flat out that the Japanese government’s espionage net containing Japanese aliens, first- and second-generation Japanese and other nationals is now thoroughly organized and working underground” (emphasis added). [30]

Every American official who received the MAGIC decodings favored relocation. The later critics, however, minimized the importance of MAGIC. John J. McCloy was Assistant Secretary of War during World War II, and testified in 1984 that “word has gone out now from the lobbyists to ‘laugh off’ the revelations of MAGIC.” [31] Rather than laugh them off, however, the highly partisan Commission on Wartime Relocation simply ignored them. In its 1982 report, Personal Justice Denied, it claimed falsely that “not a single documented act of espionage, sabotage or fifth column activity was committed by an American citizen of Japanese ancestry or by a resident Japanese alien on the West Coast.” [32]

Two years later in 1984, McCloy testified that “proof that the Commission did not conduct an investigation worthy of the name is demonstrated by the fact that it never identified the existence of MAGIC.” He said that “by the time [of] the Commission’s investigation the existence of MAGIC was almost notoriously known by all knowledgeable military and intelligence sources in this country and Japan, as well,” [33] but the commission pretended it had never existed.

Entirely apart from the MAGIC intercepts, Japanese-American disloyalty was clearly demonstrated in a little-known incident on the Hawaiian island of Niihau. A Japanese pilot shot down during the Pearl Harbor attack held 133 islanders hostage for six days — with the help of a resident Japanese alien and a Japanese-American couple, who allied themselves with the pilot. A later naval intelligence report said the Japanese-American couple “had previously shown no anti-American tendencies.” [34]

Many Japanese-Americans were loyal: approximately 9,000 served with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team in Italy and France; 3,700 others were translators in the Pacific. In all, more than 33,000 may have served the United States during the war, though some maintain that this number is too high. [35]

Many, however, were not loyal. Ninety-four percent of military-age men said they would not serve in the US armed forces (the 442nd regiment was recruited from the others). During the war, 19,000 applied to be returned to Japan, and 8,000 actually went back. There was also an active anti-American movement among the Japanese who remained. In May 1943, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson wrote about “a vicious, well-organized, pro-Japanese group to be found at each relocation center,” adding that because of them it had become dangerous for other Japanese-Americans to express loyalty to the United States. [36] In late 1942, members of the pro-Japanese faction at one center attacked and beat leaders of the Japanese American Citizens League because the League approved a resolution supporting the United States. [37] Eventually, there were so many anti-American mass meetings, mob actions, attacks on people who were suspected of being “pro-American informers” — even a “general strike” — that the American authorities separated out those loyal to Japan and incarcerated them at the Tule Lake center.

It is worth noting that Canada actually interned its Japanese-Canadians, and did not allow them to return to the West Coast of Canada until 1949. [38]

Critics have often charged that any special treatment of Japanese-Americans should have been carried out only after individual investigations. However, according to the 1940 census, there were 126,947 people of Japanese origin living in the United States. Almost 80,000 were born here, but many held dual American and Japanese citizenship. This would have been a huge population to process individually. If there had been no emergency, a case-by-case inquiry would arguably have been more consistent with standards of due process, though this would depend on whether there was a workable system for determining loyalty.

At the same time, the Japanese-American community was tightly-knit and unassimilated, and this made individual assessment difficult. Japanese were isolated partly because Americans had not welcomed an influx of Asians but also partly because of their own desire to maintain their identity. Chief Justice Harlan Stone of the US Supreme Court noted in 1943 that approximately 10,000 of those born in the United States had received all or part of their schooling in Japan, and that even those who attended school in the United States “are sent to Japanese language schools outside the regular hours of public schools in the locality.” [39] S. I. Hayakawa wrote that “reverence for the emperor was taught in the Japanese-language schools.” [40] Lack of assimilation made the community impenetrable to American intelligence, and also fertile for espionage and potential terrorism. Individual investigations were all the more impractical because potential witnesses loyal to America were subject to pressure and even physical intimidation by the pro-Japan element. The Supreme Court, in a decision written by Chief Justice Stone, agreed that it was reasonable to believe individual determinations could not be made. [41]

It is common to argue that the relocation program was “racist,” because it affected a group that was non-white. This charge completely fails to consider the American public’s emotions during the war. Americans were outraged by the attack on Pearl Harbor and the atrocities committed by Japanese forces against Americans in the Philippines. At all times, one of the reasons for relocation was to protect the Japanese-Americans themselves from this public anger. The anger is today called “racist,” but it was natural under the circumstances.

Chief Justice Stone’s comments at the time could well apply to the question of “profiling” young Arab men in the United States after September 11: “Because racial discriminations are in most circumstances irrelevant and therefore prohibited, it by no means follows that, in dealing with the perils of war, Congress and the Executive are wholly precluded from taking into account those facts and circumstances which are relevant . . . and which may in fact place citizens of one ancestry in a different category from others.” [42]

Critics have also argued that relocation was “racist” because German-Americans and Italian-Americans were left alone. This only reflects widespread ignorance. By October 1941, the government had drawn up plans for interning Germans and Italians — some of them US citizens — living in the United States. The plan went into effect the day after the Pearl Harbor attack, which was three days before the US was officially at war with Germany and Italy. The Roosevelt administration interned (as opposed to relocating) 31,275 people during the war. Of this number only 16,849 were Japanese. The rest were Germans (10,905), Italians (3,278), and a mix of other Europeans including Hungarians, Romanians, and Bulgarians (243). All Japanese internees were released by June 1946, but some Germans and other Europeans were kept locked up until August 1948. Germans and Italians were not excluded and relocated from the East Coast, but if there had been fear of German attacks (as there was of Japanese attacks), and if there had been evidence of anti-American activity among German-Americans there is little doubt the government would have acted. [43]

Another important distinction is that Germans and Italians had been in the United States much longer than Japanese, and had by assimilation clearly come to identify as Americans. [44] They served in the armed forces at much higher rates than Japanese-Americans, and almost none sought to renounce American citizenship or seek repatriation as thousands of Japanese-Americans did. [45]

Other critics of relocation argue that it was inconsistent with the government’s treatment of the large number of Japanese-Americans in Hawaii, who were allowed to stay in their homes. Why the difference? The answer is that all of Hawaii was placed under martial law and “governed like a military camp for all its inhabitants.” [46] The fact that Japanese were left where they were in Hawaii also supports the view that government policies towards them were not “racist,” but a response to the conditions at the time. A “racist” government would presumably have relocated all Japanese.

The Aftermath

The “Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act,” passed by Congress in 1948, provided for approximately $38 million to be paid for property losses. The country considered the matter closed, and for 20 years it was. The “redress movement” for reparations began in the late 1960s. In testimony before a Congressional subcommittee in 1984, Dr. Ken Masugi, then a resident fellow at the Claremont Institute, described the origins of the “concentration camp” version of what happened. He spoke of “Japanese-Americans who were activists in the sixties and then became lawyers and community organizers.” They propounded a story of abuse that met “one of the goals of the sixties protest movements: To show that America is a racist society, and that even in the case of World War II, America’s noblest foreign war, America was corrupt, having its own ‘concentration camps.'” [47]

President Gerald Ford responded to this kind of pressure in 1976 with a proclamation saying, “We know now what we should have known then: not only was [the] evacuation wrong, but Japanese-Americans were and are loyal Americans.” [48] Four years later, in the final year of the Carter administration, Congress established the “Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians,” which in early 1983 issued its tendentious report, Personal Justice Denied.

The hearings held by this Commission were, in effect, an ideological show-trial. War-time Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy has written: “The manner and the atmosphere in which the hearings were held was outrageous and a disgrace. . . . I have been before this Congress many times in hearings, but I have never been subjected to the indignities that I was at the hearings of the Relocation Commission. Every time I tried to say anything in favor of the United States or in favor of the President of the United States, there were hisses and boos and stomping of feet.” [49]

The House Subcommittee on Administrative Law and Governmental Relations held hearings in 1984, and in 1988 Congress enacted the “Japanese Money Bill,” which was ushered through Congress by Representative Barney Frank (D-MA), after he became chairman of the committee handling it. [50] Under that Act, at least $20,000 was paid to each of more than 60,000 surviving evacuees, and each received an apology. [51] The same year, the Canadians also apologized, and paid $C21,000 to approximately 10,000 survivors.

Recipients of American largesse, for whom the money was to compensate for “mental suffering and deprivation of rights,” included:

- 490 people who many years ago went to live in Japan and are Japanese citizens.

- 6,000 who were born in the centers, and thus suffered “mental anguish” when they were babies.

- The 4,300 who left the centers to go to American universities during the war.

- 1,370 Japanese aliens whom the FBI incarcerated for security reasons (in Department of Justice Internment Camps) at the beginning of the war.

- 3,500 Japanese-Americans who asked to be sent to Japan after renouncing their U.S. citizenship.

- 160 evacuees who belonged to the pro-Japanese Black Dragon Society while in the camps. [52]

Lowman tells us that “the Act also required payment [of $5,000 [53]] to several hundred Japanese who during the war were sent from Latin America to the U.S. because they were considered security risks,” and were interned here. [54] In all, the government handed out $1.6 billion. Five million dollars more were appropriated to “publicize” the Commission’s findings, and to declare it “official history.” [55]

Needless to say, the government’s actions raise a host of questions.

How does an ideologically-fabricated myth become accepted — with virtually no opposition — by the citizens of an allegedly free society? Why did our elected representatives, the press, and academic historians surrender their roles as guardians of the truth? Why do ordinary Americans come to feel a vested interest in believing that their own government was vicious and racist? Now that a precedent exists for paying “reparations” on the basis of myths, what is to stop other “aggrieved groups” from bulldozing their way to something similar? Clearly, none of this could have happened were it not for an utterly unnatural and dangerous unwillingness of whites to defend themselves.

This article is adapted by AR staff from original research by Dwight D. Murphey, professor of business law at Wichita State University. His findings first appeared in The Dispossession of the American Indian — and Other Key Issues in American History, Scott-Townsend Publishers, 1995.

___________________________________________

1 Myriam Marquez, “Avalanche is Burying Our Civil Liberties,” Wichita Eagle, Sept. 8, 2002.

2 Dillon S. Myer, Uprooted Americans, (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1971) p. 293.

3 These are the Hirabayashi case and Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944), and Ex Parte Endo, 323 U.S. 283 (1944).

4 Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Personal Justice Denied (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1982), pp. 9, 69, 99.

5 Testimony of Karl R. Bendetsen before the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, July 8, 1981, p. 140. Typescript available from national archives.

6 1981 Hearings, Testimony of Karl R. Bendetsen, p. 140.

7 1981 Hearings, Bendetsen, pp. 10, 74.

8 1981 Hearings, Bendetsen, pp. 10, 74.

9 Commission Report, Personal Justice Denied, p. 149.

10 Myer, Uprooted Americans, pp. 48, 56-7.

11 Roger Daniels et. al., editors, Japanese Americans: From Relocation to Redress (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1986), p. 61.

12 Commission Report, Personal Justice Denied, p. 145.

13 S. I. Hayakawa, Through the Communication Barrier (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1979), p. 133.

14 David D. Lowman, MAGIC: The Untold Story of U.S. Intelligence and the Evacuation of the Japanese Residents from the West Coast During WWII (No city given: Athena Press, Inc., 2000), p. 20.

15 Hayakawa, Communication Barrier, p. 132.

16 Commission Report, Personal Justice Denied, p. 205.

17 Commission Report, Personal Justice Denied, p. 203.

18 Commission Report, Personal Justice Denied, p. 181.

19 Daniels, Japanese Americans, p. 43.

20 1984 Hearings, testimony of John J. McCloy, p. 125.

21 1984 Hearings, Bendetsen testimony, p. 682; Lillian Baker, American and Japanese Relocation in World War II: Fact, Fiction & Fallacy (Medford, Oregon: Webb Research Group, 1990), p. 52.

22 Daniels, Japanese Americans, p. 188.

23 1984 Hearings, Bendetsen testimony, p. 698.

24 1981 Hearings, Bendetsen testimony, p. 71.

25 1984 Hearings, Bendetsen testimony, p. 683.

26 Wichita Eagle, Feb. 23, 1992 (article noting the 50th anniversary of the refinery shelling); Myer, Uprooted Americans, p. 24.

27 Hearings of the Select Committee Investigating National Defense Migration, House of Representatives [“Tolan Committee Hearings”], Feb.-Mar. 1942, pp. 10996, 10997, 11107, 10973.

28 1984 Hearings, Lowman testimony, pp. 431, 434.

29 Lowman, MAGIC, p. 243.

30 1984 Hearings, Lowman testimony, pp. 437, 438.

31 1984 Hearings, McCloy testimony, p. 148.

32 Commission Report, Personal Justice Denied, p. 3.

33 1984 Hearings, McCloy testimony, p. 120.

34 1984 Hearings, Lowman testimony, p. 474.

35 Baker, American and Japanese Relocation in World War II, p. 35.

36 Myer, Uprooted Americans, p. 63.

37 Myer, Uprooted Americans, p. 61.

38 1984 Hearings, testimony of John J. McCloy, p. 125.

39 Hirabayashi v. U.S., 320 U.S. 81 (1943) at pp. 96, 97.

40 Hayakawa, Communication Barrier, p. 135.

41 Hirabayashi, p. 99.

42 Hirabayashi, p. 100.

43 Arnold Krammer, Undue Process: The Untold Story of America’s German Alien Internees (New York: Rowan and Littlefield, 1997).

44 See Sen. Hayakawa’s observation about this at Hayakawa, Communication Barrier, p. 583; and the comments by Madera, California, officials on the same point, Tolan Committee Hearings, Earl Warren testimony, 10995.

45 Krammer, Undue Process.

46 Hearings [1984 Hearings] before the Subcommittee on Administrative Law and Governmental Relations of the Committee on the Judiciary, U.S. House of Representatives, June 20, 21 27 and Sept. 12, 1984, page 583, testimony of Dr. Ken Masugi.

47 1984 Hearings, Masugi testimony, p. 579.

48 Daniels, Japanese Americans, pp. 188, 5.

49 1984 Hearings, McCloy testimony, p. 125.

50 Lowman, MAGIC, p. 111.

51 Wall Street Journal, September 10, 1991, letter from William J. Hopwood.

52 Wall Street Journal, Hopwood letter.

53 Lowman, MAGIC, p. 119, footnote 23.

54 Lowman, MAGIC, p. 119.

55 Lowman, MAGIC, pp. 2, 82, 83.