Woodrow Wilson: Good or Bad for Whites?

Hubert Collins, American Renaissance, October 30, 2015

There is a general consensus on the reputations of many presidents, but there is disagreement about Woodrow Wilson. For students of foreign policy, his name is synonymous with center-left arguments for a militarized foreign policy and “humanitarian” intervention abroad–particularly for wanting to make the world “safe for democracy.” In international relations, a great deal has been written about his famous “Fourteen Points” and his ill-fated attempt to create an international body to tame the world’s ills.

Republicans, especially lately, have come to see him as one of the earliest Democratic villains–a technocratic and elitist patriarch who set the stage for FDR, LBJ, and of course, Barack Obama. Democrats, on the other hand, think he was an effective politician who brought the party out of William Jennings Bryan’s populism into a more serious and international mindset. They still name journals and think tanks after him. Libertarians loathe him for taking America into the First World War, creating the Federal Reserve system, and establishing the first permanent income tax.

How was Wilson on race? In his personal beliefs, and in many of his official policies, Wilson was very sensible, but his larger legacy was not good for white America.

Born in Staunton, Virginia, in 1856, Wilson was raised by parents who supported the Confederacy. His mother nursed wounded Southern soldiers at a local hospital, and his father, a minister, helped organize the Presbyterian Church of the Confederate States of America. The young Wilson even watched Union soldiers escort Robert E. Lee through town after the surrender at Appomattox.

Growing up during the war and coming of age under Reconstruction clearly marked his racial views. While still a student at Princeton, Wilson supported Samuel J. Tilden in the presidential election of 1876, writing in his diary, “I most sincerely hope that it [America] will be sensible enough to elect Tilden as I think the salvation of the country from frauds and the reviving of trade depends upon his election.”

Tilden, a Democrat who had been critical of Abraham Lincoln and opposed the Radical Republicans, represented a chance for Southerners to break the hated Republican stranglehold on the executive branch and finally end Reconstruction. His opponent, Rutherford B. Hayes, had fought for the Union and would be the natural heir to the corrupt presidency of Ulysses S. Grant.

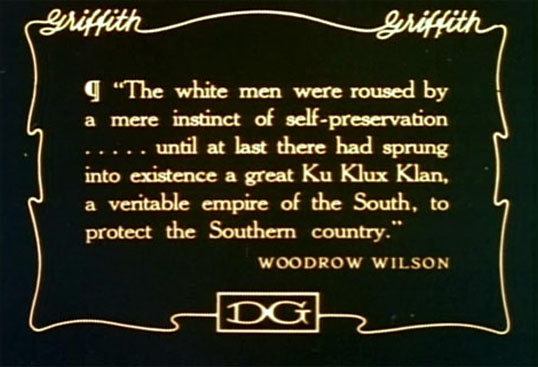

Tilden narrowly lost, but Wilson continued as a defender of the Lost Cause. After Princeton, he began a career in political science, and much of his writing shows a strong sense of pride in his race and in the Confederacy. In his multi-volume, A History of the American People (1902), he wrote of Reconstruction:

The white men of the South were aroused by the mere instinct of self-preservation to rid themselves, by fair means or foul, of the intolerable burden of governments sustained by the votes of ignorant negroes and conducted in the interest of adventurers: governments whose incredible debts were incurred that thieves might be enriched, whose increasing loans and taxes went to no public use but into the pockets of party managers and corrupt contractors. There was no place of open action or of constitutional agitation, under the terms of reconstruction, for the men who were the real leaders of the Southern communities.

Even more boldly, he described the Ku Klux Klan and similar groups as noble vigilantes who fought tyranny in the occupied South:

It became the chief object of the night-riding comrades to silence or drive from the country the principal mischief-makers of the reconstruction regime, whether white or black. The negroes were generally easy enough to deal with: a thorough fright usually disposed them to make utter submission, resign their parts in affairs, leave the country–do anything their ghostly visitors demanded. But white men were less tractable: and here and there even a negro ignored or defied them. The regulators would not always threaten and never execute their threats. They backed their commands, when need arose, with violence. Houses were surrounded in the night and burned, and the inmates shot as they fled, as in the dreadful days of border warfare. Men were dragged from their houses and tarred and feathered. Some who defied the vigilant visitors came mysteriously to some sudden death.

Wilson’s unapologetic views did not change when he won the 1912 election. As the first Southern president since a decade before the Civil War, his inauguration filled the capital with “rebel yells and the strains of ‘Dixie’.” For many Southerners, it seemed that “home rule” was at hand again.

In some ways, this was true. The epic film Birth of a Nation, which portrays the Confederacy and the KKK sympathetically, was released during his tenure. He arranged for a special White House showing, and remarked that the movie was “like writing history with lightning.” He was the first president to lay a wreath at the Confederate Memorial in Arlington National Cemetery. Every succeeding president, even Mr. Obama, has at least sent a wreath to the memorial even if not all have laid it themselves. On the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, President Wilson delivered a speech at the battlefield to an audience that included Confederate and Union veterans, praising them all as “gallant men in blue and gray.”

After he took office, Wilson began implementing measures on race almost immediately. He segregated the Navy and large swathes of the civil service, and made it a requirement to attach a photo to applications for federal jobs to make it easier to screen out blacks. He supported legislation to make interracial marriage in Washington, D.C., a felony.

Wilson appointed very few blacks to office. His predecessor, William Howard Taft, appointed 31 blacks, but Wilson appointed only nine, all but one of whom were carryovers from Taft’s administration. Wilson also had the Washington, D.C., police and fire departments stop hiring blacks entirely.

In 1914, a delegation from a black advocacy group called the National Independent Political League went to the White House to protest his policies, but Wilson would not bend. To Monroe Trotter, the group’s leader, he explained, “Segregation is not humiliating, but a benefit, and ought to be so regarded by you gentlemen.” When Trotter, a Harvard graduate, disagreed, Wilson replied, “If this organization is ever to have another hearing before me it must have another spokesman. Your manner offends me.”

Wilson probably received more black votes than any president before him but did not let that sway him. “If the colored people made a mistake in voting for me, they ought to correct it and vote against me,” he said. This is in stark contrast with Teddy Roosevelt, who invited Booker T. Washington to dinner at the White House in 1901.

Even in international affairs, on which Wilson’s liberal reputation largely rests, he kept race in mind. During the peace talks after the First World War, Japan was emboldened by the acquisition of German islands in the Pacific, and proposed that a “racial equality clause” be included in the Covenant of the League of Nations. A majority of the delegates voted for the clause, but Wilson, who chaired the meeting, made an unprecedented ruling, insisting on unanimity. The Japanese were furious.

With Russia weakened by civil war between the Whites and the Reds, Japan had designs on Siberia. Wilson had Secretary of State Robert Lansing send a strong message to the Japanese that meddling would not be tolerated. Wilson also refused to meet representatives from Vietnam who wanted to end French colonial rule.

There was a KKK resurgence during Wilson’s presidency. As his historical writings suggest, Wilson saw no problem with this, and let the Klan grow without harassment from the federal government. By the 1920s, the Klan was a serious political force, which supported the national-quotas immigration legislation of 1924.

Wilson also surrounded himself with like-minded men. His secretary of the treasury and son-in-law, William Gibbs McAdoo, was a staunch segregationist whose aid and endorsement from the KKK in 1924 very nearly made him that year’s Democratic nominee. The man who got the nomination was John W. Davis, who had been Wilson’s first solicitor general, and then his ambassador to the UK. Decades later, he defended segregation in Brown vs. Board of Education.

Wilson’s attorney general, A. Mitchell Palmer, made a name for himself dealing harshly with the Communist-fueled race riots in the summer of 1919. To this day, leftists bemoan the now infamous “Palmer Raids.” The postmaster general (a very important position at that time) for both of Wilson’s terms was Albert S. Burleson, the son of a Confederate officer and grandson of a soldier for the Republic of Texas, who insisted that the post office be segregated.

Wilson never made any excuse for his policies. Never much of a constitutionalist, he thought government should recognize the newly discovered sciences of the time, and proposed to “interpret the Constitution according to Darwinian principle.” Although he never took national steps towards eugenic policies, as governor of New Jersey he proudly signed a law requiring sterilization of criminals and the mentally retarded.

For Wilson, the solution for the world’s ills, racial and otherwise, was state power. During his academic career he was deeply influenced by G.W.F. Hegel, who famously wrote, “The march of God in the world, that is what the state is. The basis of the state is the power of reason actualizing itself as will.” Wilson thought little of the Constitution’s “checks and balances” and believed that “men are as clay in the hand of the consummate leader” and that “the President is at liberty, both in law and in conscience, to be as big a man as he can.”

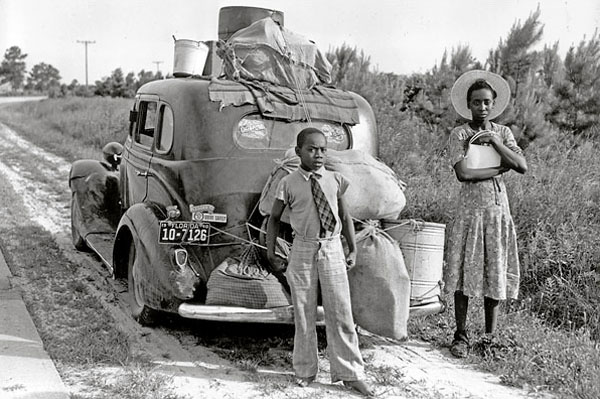

Wilson used his executive power to enforce segregation but his presidency unwittingly brought integration in the North. With the industrial buildup and eventual entry into First World War, the North’s factories needed cheap labor. Blacks who wanted something better than agricultural toil went north in what is called “the Great Migration.”

Between 1914 and 1920, around half a million Southern blacks moved north–at a time when the American population was one third its current size. The black populations of Chicago, Buffalo, and New York more than doubled between 1910 and 1920. Those of Detroit and Cleveland more than tripled, and the black populations of Cincinnati, Columbus, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Milwaukee all rose between a third and a half. Northern cities that had been 1 percent black at the turn of the century were 7, 8, and even 10 percent black by 1930. This started the decline of many northern cities, for which Detroit is the symbol. If the country had steered clear of war in Europe and industrialized more slowly, it is possible to imagine an Ohio as white as Oregon, and an Illinois as white as Idaho.

This is the great irony of Wilson’s presidency. Historians debate whether he had been secretly waiting for an opportunity to go to war or had a change of heart. He campaigned for re-election in 1916 as the peace candidate, but he also approved the National Defense Act of 1916 that authorized a military industrial build-up and provided for greater government control of manufacturing.

Once America was at war Wilson went all the way. There was a national draft, and the Espionage Act limited press, freedom of speech, and the right to assembly. Wilson’s War Industries Board imposed greater state control on the arms industry. Whether he planned it from 1914 onwards or begrudgingly accepted it in 1917, Wilson conducted war as he did everything else: with massive government involvement. He also certainly saw it as part of his desire for a more democratic world, a task fit for large and powerful states.

The integration Wilson caused by America’s entry into the war was an example of what the French economist Frédéric Bastiat meant when he wrote of the unseen: “. . . a law produces not only one effect, but a series of effects. Of these effects, the first alone is immediate; it appears simultaneously with its cause; it is seen. The other effects emerge only subsequently; they are not seen.”

The Great Migration might have happened without Wilson’s war. The industrialization of the North may have been inevitable. But without the war the Great Migration might not have been so “great,” and Wilson’s policies certainly did nothing to slow it. Blacks remaining in the South would have been no gift to Southerners, but at least it was the status quo.

Even a sound politician can cause accidental damage, and Wilson’s record shows that an intrusive state is always a potential threat. In our time, attempts to keep America safe from terrorism prompted military interventions that have contributed to refugee crises and a mass migration to Europe. Before Muammar Gaddafi was driven out of office, his son Seif warned, “Libya may become the Somalia of North Africa, of the Mediterranean. You will see the pirates in Sicily, in Crete, in Lampedusa. You will see millions of illegal immigrants. The terror will be next door.” Sweden today is almost 2 percent Iraqi, and Iraqis started coming there only in 2002.

This is not to say that all government action should be eschewed, or even feared, but it should always be carefully considered. It was not so long ago that many white advocates supported Ron Paul, but with the increasingly obvious uselessness of Rand Paul and the Tea Party, that anti-state inclination has faded. Today there is much more interest in non-ideological figures such as Donald Trump and in foreign pro-state parties such as the French National Front, the Danish Peoples Party, and Fidesz in Hungary.

On the other hand, to the extent that non-interventionist parties such as UKIP and the Austrian Freedom Party take strong positions on immigration, they deserve our support. Fighting dispossession is our number-one goal, and we must set aside whatever political differences we may have in order to achieve that goal.

Under virtually any conception of the state, government has the power to control borders, and that is the first line of defense against dispossession. What happens internally is a different matter, but as Wilson’s record shows, even a combination of executive power and good intentions is not always enough.