Is Democracy Possible in America?

Jared Taylor, American Renaissance, March 8, 2013

Subscribe to future audio versions of AmRen articles here.

Alain de Benoist, The Problem of Democracy, Arktos Media, 2011, £10.50, 103 pp.

There may be no better place or time to meditate on the defects of democracy than the United States in 2013. What an absurd figure we cut in the world, as we try to impose on Afghans and Iraqis a form of government utterly alien to them, while our own rulers lurch from crisis to failure back to crisis.

Alain de Benoist, one of the sharpest thinkers of the French Right, wrote The Problem of Democracy in 1985, but its insights are as fresh as ever. This is a short book, but one dense with ideas. Thanks to Arktos Media, it is finally available to English readers in a fluent translation, with explanatory footnotes and a preface by Tomislav Sunic.

Mr. de Benoist has written as powerful a critique of democracy as one is likely to find — so powerful that it is almost a surprise to find that he concludes with a prescription for how democracy could be made to work. Needless to say, both his critique and his prescription, though rivetingly relevant to the United States, are unknown in this country.

Mr. de Benoist begins by pointing out that “democracy” is so mystical a term that virtually every government on earth claims to be “democratic.” The communist countries of East Europe were “democratic republics,” and African dictators claim to be democrats.

Westerners generally think democracy — loosely defined as free participation by the people in public life — is unquestionably the best form of government. Mr. de Benoist argues that no form of government is best for all countries at all times. Democracy, moreover, is European and heavily influenced by the Enlightenment and Christianity (an organization of celibate priests could not have hereditary offices, so voting was essential to church government). The leftist idea that the whole world should embrace democracy is pitiably ethnocentric.

Nor, as is commonly argued, is Western democracy a recently evolved and therefore particularly advanced form of government. The oldest parliament in the West, the Icelandic Althing, was established in 930, and there were clearly democratic tendencies in the ancient Italian republics, the Hanseatic municipalities, and the charters of the Swiss cantons.

Nor is it accurate to find stark differences between democracy and despotism. Unlike the Orientals, Indo-Europeans have seen very little despotism. In the Illiad, in ancient Rome, in Vedic India, and among the Hittites, there were popular assemblies that decided civil and military matters. In the West, kings were elected, and monarchy did not become generally hereditary until the 12th century. Even then, kings shared power with elected parliaments. In the West, virtually every system has therefore been a mix of collective and solitary rule. Some would even call the Athenian system not so much a democracy as an extended form of aristocracy.

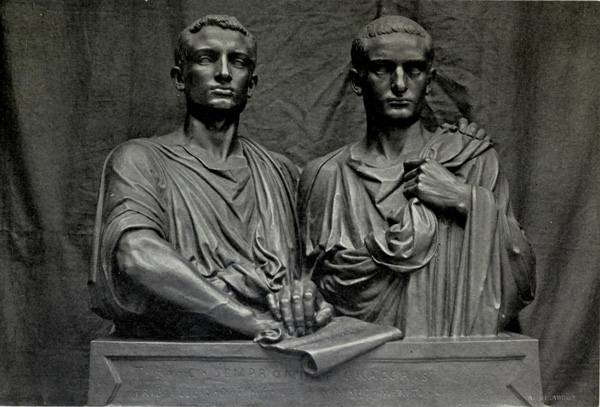

The Gracchi were brothers who served as tribunes. Elected by the plebs, they could veto most government acts in ancient Rome.

The defects of democracy

Mr. de Benoist notes that it has long been common to scoff at the idea of letting ordinary people have a role in government. As Hyppolyte Taine (1828-1893) wrote, “Ten million ignorant men cannot constitute a wise one.” Ernest Renan (1823-1892) wrote that elections mean a “destiny committed to the caprice of an average of opinion inferior to the grasp of the most mediocre sovereign called to the throne by the hazards of heredity.” René Guenon believed that “the opinion of the majority cannot be anything but an expression of incompetence.”

The best known American exponent of this view was H.L. Mencken, who wrote, “If it were actually possible to give every citizen an equal voice in the management of the world . . . the democratic ideal would reduce itself to an absurdity in six months. There would be an end to all progress.”

Many people therefore call democracy a dictatorship of mediocrity. Since politicians must appeal to the masses, elections throw up third-rate men. And because politicians must be reelected they never think in the long term and can never take necessary but unpopular steps.

In a democracy, the majority is supposed to rule, but Mr. de Benoist notes that this is an expression of numbers, not wisdom. “Quality cannot stem from quantity,” he writes. “The idea that authority, a quality, may stem from numbers, a quantity, is rather disturbing.”

A majority vote is supposed to reflect the sovereign will of the people, but Mr. de Benoist is skeptical of a sovereign will that expresses itself as half the votes cast, plus one. Moreover, majorities are constantly shifting; does that mean the will of the people is constantly shifting? If so, are the people competent to rule? Nor does majority rule take intensity of feeling into account; the vote of a coin-flipper counts the same as that of a passionate partisan.

A different approach is to claim that the majority view is the absolute and permanent will of the people — so long as it is one’s own view. On this theory, anyone who expresses a contrary view can be exterminated. This was Lenin’s and Robespierre’s version of democracy.

In these less philosophical times, a majority vote is seen as just a tool, a transient statistic that permits government to operate, rather than a significant expression of the people’s will. Modern democracies accept the idea of permanent pluralism and the proliferation of parties. But this concedes that there is no real voice of the people; only clashing factions, none of which seeks the national good.

When there are many parties there is never a majority — only shifting, unstable coalitions — which means impotence and irresponsibility. Whether there are many parties or few, parties become ends in themselves. Their survival, along with their hangers-on, becomes more important than whatever ideas they once represented.

No matter what is claimed in democracy’s name, it is actually a system of rule by minorities, since only elected officials actually rule. Moreover, they routinely break their election promises and are always free to flout the wishes of their constituents. Mr. de Benoist writes that when a voter hands over his decision-making power to a representative, “he is making use of his liberty only to renounce it.” This legitimizes the power of politicians over a passive population.

Even Jean-Jacques Rousseau scoffed that “the English people thinks it is free; it is greatly mistaken, it is free only during the election of members of Parliament; as soon as they are elected, it is enslaved, it is nothing.”

At the same time, money rules politics. A poor man can hardly become a candidate, much less win an election. And because having power is the best way to raise money, the political class perpetuates itself. Moreover, Mr. de Benoist notes that “the tyranny of money clearly goes hand-in-hand with corruption and financial scandals.” Money proves the bankruptcy of the process itself: Most of it is spent on television advertising, which is the most insulting form of political discourse.

That voters can be swayed by television advertising only shows how powerful the media are. As Mr. de Benoist notes, “Popular will is thus being increasingly fabricated by using methods to condition public opinion.”

This makes fools of the sovereign people:

The fact that elections may be free is meaningless if opinion-forming is not. . . . Only a small number of people hold opinions that may be regarded as genuine convictions. The vast majority of people have no real opinions, but only impressions . . . for they are shaped by events, propaganda, and various forms of conditioning.

The candidates themselves are caught in the same snare. Modern political platforms are often based on surveys, which give everyone the same result. Therefore, writes Mr. de Benoist, “Out of demagogy and a concern to please, candidates all end up saying much the same things to everyone.”

And what they say is mundane rubbish: “In a society pervaded by the ideal of egalitarianism, the very notions of grandeur and collective destiny raise suspicion.” American politics, in particular, is all talk of money, spending, and budgets. It is the language of bookkeeping, not of destiny, greatness, or overcoming.

In modern politics it is common to win by narrow margins. This means no party or politician has a real mandate, and so cannot implement a program. It means politicians always try to win over their opponents’ supporters, which again leads to numbingly uniform policies.

This means that “voters are free to opt among different parties because they are prevented from opting among different ideas — for these ‘different’ parties are increasingly reasoning all in the same way.”

As a consequence, “Western man has never been more rightfully indifferent towards the ‘liberties’ he enjoys — although his illusion of having these liberties shackles his will to rebel.”

Although voters may be unable to articulate their frustration, sham choices are one of the great sources of today’s voter apathy. It is only natural that voter participation declines, and even important offices are won with pitifully small percentages of eligible voters. And who benefits from voter apathy? A self-perpetuating political class that is increasingly protected from discerning and motivated voters.

Voters therefore almost never vote “for,” but “against.” In a democracy, people are supposed to choose candidates who embody their will and desires. Instead, they vote against candidates who most clearly flout those desires.

As Mr. de Benoist explains:

Democracy has changed. It was initially intended to serve as a means for the people to participate in public life by appointing representatives. It has instead become a means for these representatives to acquire popular legitimacy for the power which they alone hold. The people are not governing through representatives; the are electing representatives who govern by themselves.”

Mr. de Benoist writes that far from being exercises in sovereign power, “elections are a ceremony for bestowing legitimacy: the people crown a candidate or consecrate a president without having much choice in the matter.”

Defenders of democracy

How do defenders of democracy answer their critics? Mainly by arguing that despite its defects, democracy is a government of limited powers and can never subject the people to tyranny. This is false. Any system of government can lead to tyranny. We already live under a “soft” despotism that would be the envy of Louis XIV or Ivan the Terrible. No king could make his subjects account for every penny of income and then dictate exactly what percentage to hand over in taxes. No “absolute” monarch ever told his subjects where they could have a smoke, or tell him how long his employees were to work. Our government even claims the right to kill American citizens overseas without a trial; it need only call them “enemy combatants.”

As Mr. de Benoist observers, “it is not the idea of ‘absolute power’ which democracy rejects, but rather the idea that such power may be the privilege of a single person.”

Nor is democracy clearly superior to what Westerners dismiss as “dictatorship.” Would Singapore be a better, happier place with Western-style elections and political squabbling? Would China? Is Algeria, which has been ruled since independence by a single party, more poorly governed than India? Was Spain under Franco any worse than the current wreck?

Francisco Franco was dictator of Spain from 1936 until his death in 1975. He oversaw the fifteen year economic boom known as the “Spanish Miracle.”

Westerners claim that even if Singapore or China have dramatically improved living standards, their systems are inferior because the people do not have free speech. Mr. de Benoist lays bare this hypocrisy. Many European countries ban speech that might “stir up racial hatred,” and others even forbid dissident commentary on certain historical events.

Mr. de Benoist notes that if “stirring up hatred” were grounds for muzzling citizens, Communists and socialists should be the first targets, since their vocation is stirring up class hatred. He argues that any brisk attack on a political opponent could “stir up hatred,” and that a consistent application of “hate speech” laws would outlaw all political speech. The West makes a fetish of certain subjects and treats them just as hysterically as “dictators” treat criticism of the regime — and for the same reasons.

Mr. de Benoist notes that Germany even bans specific political movements, of both the Right and Left:

[This requires] believing that the ruling system is so excellent that once it has been established, we have the right to proscribe all possibilities of choosing a different one. All radical dissent — which is to say, all genuine dissent — is thus banned. But can we still call this a democracy?

How to make democracy work

After this blistering critique, what is left of democracy for Mr. de Benoist to support? To answer that question he takes us back to ancient Greece. He notes that in Athens, each citizen had an equal voice in the ekklesia or assembly, but emphasizes that “the crucial notion here is not equality but citizenship.” Slaves had no voice, not because they were slaves but because they were not citizens, and almost without exception, the only way to become a citizen was to be born of an Athenian mother and father.

As Aristotle pointed out, Athens came first and citizens were born into it. Mr. de Benoist notes that “this view stands in contrast to the concept of modern liberalism, which assumes that the individual precedes society and that man, qua individual, is at once something more than just a citizen.”

Thus, the main difference between ancient Greek democracy and our own is not what are always told: that theirs was direct democracy whereas ours takes place through elected representatives. Instead, we have completely different conceptions of society:

Ancient democracy defined citizenship by one’s origin, and gave citizens the opportunity to participate in the life of the city. Modern democracy organizes atomized individuals into citizens, primarily viewing them through the lens of abstract egalitarianism. . . . The meaning of the words “city,” “people,” “nation” and “liberty” radically changes from one model to another.

Mr. de Benoist continues:

The effective functioning of Greek democracy, as well as of [ancient] Icelandic democracy, was first and foremost the result of cultural cohesion and a clear sense of belonging. The closer the members of a community are to one another, the more likely they are to have common sentiments, identical values, and the same way of viewing the world and social ties, and the easier it is for them to make collective decisions concerning the common good without the need for any form of mediation. Modern societies . . . have ceased to be places of collectively lived meaning.

Mr. de Benoist writes that modern democracy that ignores the crucial element of peoplehood is an American invention. It is no accident that it sprung up among people who do not even have a word that is the equivalent of Volk in German or popolo in Italian. It is democracy without demos.

Mr. de Benoist dislikes the all-men-are-created-equal phrase of the Declaration but, if anything, dislikes even more the idea that men are endowed by their Creator with unalienable rights. The rights that matter in a democracy, he writes, do not come from God but from citizenship and common heritage. The American conception is doomed from the start because “where there is no folk but only a collection of individual social atoms, there can be no democracy.”

He quotes Raymond Polin (1910 — 2001) on the only proper basis of government:

The source of its legitimacy lies with the body of principles on which the deep-seated consensus of the nation is based. . . . Resting on a given conception of man, of society and politics, this deep-seated consensus carries an obligation to build the future history of the nation according to the inspiration of its spirit.

Mr. de Benoist believes that a healthy democracy transcends rivalries:

In this context, one should not underestimate the importance of the genuine phenomenon of national and folk consciousness, by means of which the collective representations of a desirable socio-political order are linked to a shared vision, comprised of a feeling of belonging that presents each person with imperatives transcending particular rivalries and tensions.

Under these circumstances democracy provides the fairest way to ensure that elites are genuinely worthy. And democracy does not try to make people equal; only to give them an equal chance to be unequal.

In such a democracy citizens would take an active part in public life, and with modern technology their democracy could be almost as direct as Athenian democracy. People would be active in local affairs and vote in frequent plebiscites and referenda. As Mr. de Benoist writes, “The people should be given the chance to decide wherever it can; and wherever it cannot, it should be given the chance to lend or deny its consent.”

The actual mechanisms of democracy — which readily degenerate into the spectacles of vulgarity by which America elects its President — are much less important than citizen participation. Mr. de Benoist believes that a genuinely constituted people could embody Moeller van den Bruck’s (1876-1925) definition of democracy: “a folk’s participation in its own destiny.”

The United States

For American readers, The Problem of Democracy throws a harsh light not only on our political system but on even the theoretical possibility of reform. Every one of Mr. de Benoist’s criticisms of democracy applies to the United States — and every one of his conditions for its success is missing.

Americans — fatally infatuated with their illusions — are the very people who should read this book but are the very people who will not. If democracy is “a folk’s participation in its own destiny,” we can conclude that America, without a folk, has no destiny.