Report from Australia

Jared Taylor, American Renaissance, September 21, 2012

I was invited to give a talk in Sydney by an Australian group called Klub Nation that opposes Third-World immigration to their country. On September 15, I spoke for about 40 minutes on the importance of racial consciousness and the need to control immigration. The talk was warmly received, and a very well informed audience kept me on my feet for another 40 minutes of questions.

After I spoke, Professor Drew Fraser gave a talk on the importance of WASP consciousness, and afterwards he and I debated whether it made sense to appeal specifically to American WASPs. Prof. Fraser argued that ethnic consciousness is more powerful than racial consciousness and would be a better way to mobilize people. I argued that at least in the United States, appealing to WASPs would be divisive, and that when white Americans have a group consciousness that goes beyond food and holidays to include a political dimension, it is racial rather than ethnic.

This was my first visit to Australia, so I arrived a few days early to poke around. There is much to see in and around Sydney.

I stayed in Parramatta, which is a suburb to the west of Sydney that has become the home of many of the “new Australians” who are changing the face of the country. There is a train that runs through Parramatta into Sydney, and I was surprised to be one of just a handful of whites on board. The rest were Orientals, Middle-Easterners, dark-skinned Indians, and a sprinkling of Africans. It is a different racial mix from that of the United States, and it was not always easy to guess the origins of my fellow passengers. Many spoke languages I did not recognize.

Australia does not keep a racial count of its population, so there are no official figures on the percentage of non-whites, but estimates put them at 15 to 20 percent. Most live in big cities such as Melbourne and Sydney, while the back country is still overwhelmingly white. I cannot guess the non-white population of Sydney, but they are certainly everywhere you look.

Many of the people a tourist would deal with, such as train-ticket sellers, shop keepers, and counter clerks are “new Australians” from Asia and the Middle East. They tend to have the same affectless, minimalist view of customer service that their counterparts have in the United States. Museums and historical sites, however, were staffed by white Australians who were uniformly polite and agreeable.

Australia was first settled in 1788, so there are no buildings older than that, but early convict barracks, government buildings, and even a few early 19th-century private houses are carefully maintained and open to visitors. Parramatta was one of the first settlements, because the land in Sydney was salty and infertile. Early buildings there are well maintained, and offer excellent guided tours.

Although Parramatta must be one of the most heavily non-white cites in Australia, the historical preservation effort seems to be entirely white. I did not see a single “new Australian” among the staff, guides, or visitors. It is like visiting the Smithsonian museums in Washington, DC: diversity outside, white visitors inside.

In Sydney, I stopped by the Parliament House, where the state government of New South Wales meets. The upper house was in session, and from the gallery I watched members of the opposition questioning ministers. There is not much worry about security: From the gallery I could have walked right onto the floor of the chamber. I had gone through a security check to get into the building, but when I left the gallery I went out to the street through an unguarded gate. It is pleasant to be in a country that trusts its people.

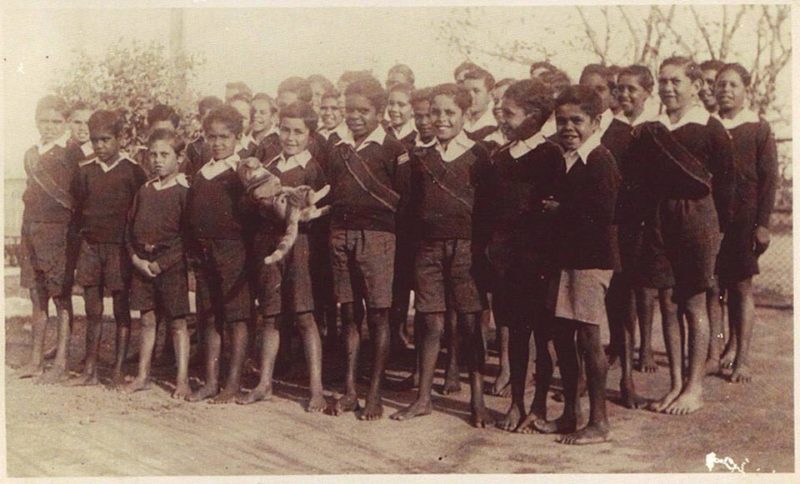

Parliament House has an exhibition room. At the time of my visit, there was a display called “In Living Memory” about the activities of the now defunct Aborigines Welfare Board of New South Wales. The exhibit was a breast-beating portrayal of the early 20th century program of taking aboriginal children — many of them part white — out of the bush, and putting them in boarding schools. The plan was to give them Anglo-Australian training so they could get jobs in the modern economy, but the program is now reviled as cultural genocide. The captions of the photographs contained such phrases as “children smile grimly as . . . .”

It is my impression that official Australian remorse about aborigines may be even more heavy-handed than American remorse for slavery or dispossession of the Indians. Public buildings often have Aborigine-motif decorations. A restaurant in the Sydney Opera Hall, for example, has a sculpture of didgeridoos, an aboriginal musical instrument (see one played here). Walkways in Parramatta are decorated with aboriginal-style drawings.

The Australian Museum in Sydney has a wing devoted to Aboriginal artifacts, but they are unimpressive. There are boomerangs and “message sticks” (sticks with grooves and notches carved on them to convey messages), and kangaroo-skin cloaks, but not much else. As I walked through the museum, I caught sight of some very striking masks and for a moment thought that Aborigines must have a real creative streak after all. The masks turned out to be from New Guinea.

More impressive to me than the Aboriginal exhibit was a display of all the Australian sea creatures that can kill you: not just sharks, but box jellyfish, lion fish, blue-ringed octopi, cone shells, and stone fish.

Did I see any aboriginals while I was in Sydney? I don’t know. Australia seems to follow the one-drop rule, and many people who look white claim to be aboriginal because of the benefits and social cachet. Aboriginal traits are generally recessive, so even a first-generation cross between a pure-blood aborigine and a white could be hard for an outsider to place.

On the Friday evening before my talk, Prof. Fraser and his wife Kathe took me to see the second night of a new play called Australia Day. The title comes from Australia’s annual celebration of the arrival of the first convict fleet in 1788 and is a national holiday. The play, written by the well known political satirist Jonathan Biggins, is set in a small Australian town, where the town council is planning this year’s celebration.

Prof. Fraser warned me to expect an evening of unrelieved multi-culti, but we were pleasantly surprised. The “bigot” who yearns for the days before Third-World immigration is likeable and has clever lines. His foil is a Green Party town councilor who mouths platitudes, and is exposed in the end as a scheming, dishonest politician, like all the rest. There are some forthright arguments against immigration, though the playwright did the safe thing and put them into the mouth of an Australian-born Oriental. In all, it was a clever, entertaining performance, and I was sorry when it ended. I did not notice a single non-white face in an audience that must have numbered more than 600.

Perhaps the most impressive and moving place I visited was the ANZAC memorial in Hyde Park in Sydney. It was dedicated in 1934 to the people of New South Wales who served in The Great War. ANZAC stands for Australia New Zealand Army Corps, which was the name of the force that served in Europe, and even individual soldiers are referred to as Anzacs. In later years, the memorial has been rededicated to all Australians who served their country.

There is a spacious, dignified rotunda inside, with 120,000 gold stars embedded on the underside of the dome — one star each for the men and women of New South Wales who rallied to the flag during The Great War. At the center of the memorial is a very striking statue of women carrying a dead soldier who has come home, like the Spartan, on his shield.

There are small displays inside the memorial commemorating the major wars Australia has fought. The first engagement of Australian troops outside their country was during the Boer War in South Africa. Since then, whenever Great Britain was at war, Australia loyally fought for the mother country. The very day after Britain declared war on the Kaiser, Australian Prime Minister Joseph Cook declared that “when the Empire is at war, so is Australia.” The United States waited three years before going to war.

Likewise, during the Second World War, the United States did not join the fight until it was attacked, but Australia immediately declared war. As Prime Minister Robert Menzies explained, “Britain is at war; therefore Australia is at war.”

Australians had no quarrel with Boers or Germans, and their country had no vital interests at stake (the Japanese bombed Darwin during the Second World War, but Australia was already a combatant). Australians rallied to Britain because they were overwhelmingly of British stock and considered themselves the same people. If Britons were dying Australians would die beside them.

I visited the ANZAC memorial on a sunny day, and Hyde Park was full of visitors. There were hundreds of “new Australians” outside the memorial, but not one inside. The call of the mother country no doubt means nothing to them.

I read a history of Australia before I went to Sydney, a book called Australia by a British author named Frank Welsh. I was curious to see how he would treat the “White Australia Policy” that restricted immigration to whites, and was not fully dismantled until the 1970s. He described it as “bigoted” and “damaging,” but never explained why it was wrong. No doubt, in these enlightened times, no one needs to be told why it is wrong for a nation built by whites to stay white.

But Mr. Welsh’s praise for the consequences of massive non-white immigration is a miracle of stupidity: “From being a colonial backwater searching for an identity, Australia has become a multi-cultural society.”

If men and women who were proud subjects of the British crown really had been “searching for an identity” how could they possibly have found one by importing millions of foreigners who have nothing in common with the founding stock? This is the foolishness that now passes for wisdom.

A minority of Anglo-Australians fully understand the terrible mistake their country made when it abolished the “White Australia Policy.” They are working hard to preserve the nation of their ancestors and they deserve our full support.