July 2010

| American Renaissance magazine | |

|---|---|

| Vol. 21, No. 7 | July 2010 |

| CONTENTS |

|---|

War With the Comanche

Whiting Out White People

O Tempora, O Mores!

Letters

| COVER STORY |

|---|

War With the Comanche

How a proud people were finally defeated.

Fort Sill, north of Lawton, Oklahoma, is home to the Army’s Field Artillery School as well as many field artillery brigades. Over the decades, thousands of Americans have learned how to crew cannon there, and I am one of them. A posting to Fort Sill allowed me to explore what remains of the Wild West when I was off duty. I’d always been a fan of Westerns and of the real history of America’s pioneering conquest of the continent, and the Lawton area was and is the center of Comanche territory.

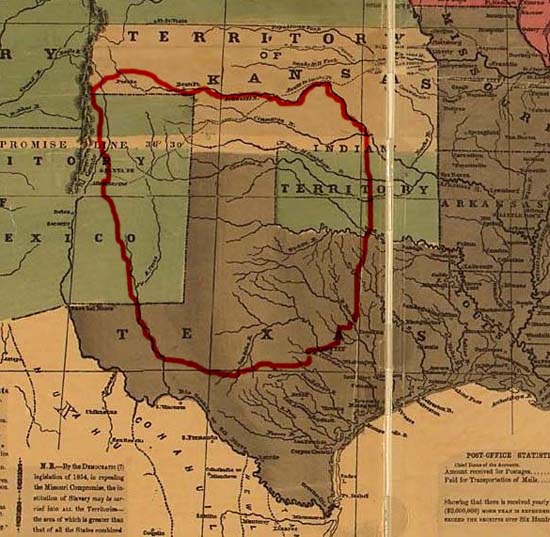

“Comancheria,” the former territory of the Comanches.

During the early days of the Texas Republic, the Comanche were the world’s best light cavalry. In fact, they were such fantastic fighters that the Spanish never even tried to subdue them, and the Comanche halted the expansion of settlements into the panhandle and northern Texas for nearly 50 years. Yet the Comanche today are a pitiful group, the defeated remnants of a terrible racial conflict.

Everywhere you go in Lawton, you see obese Indians. In Oklahoma each tribe has its own license plates, so you can tell a person’s tribe by watching him get into his car. (I tried to get a license plate that said “Comanche” but the DMV would not give me one.) Sometimes it seems as though all the Comanche are unhealthy; the white man’s diet does not seem suited to a people adapted to living on game from the North American prairie. When the Comanche get sick they go to the Public Health Service Indian Hospital at the eastern end of Lawton. If you drive by you are likely to see ancient Indians — poor and disheveled — holding out their thumbs for a ride. Their hands tremble.

It seems that the Comanche are as badly adapted to the white man’s economy as to his diet. I once watched a heavy Comanche woman slowly pushing pennies towards a white cashier. She carefully slid each coin across the counter as though it was very difficult to part with.

The Comanche’s misery is the result of their absolute defeat during a fierce conflict with whites in the 19th Century. The Comanche War, as that conflict has come to be known, was lengthy and cruel. This terrible war that cursed both the Indians and the Americans was largely inherent in their circumstances; different races and cultures, especially aggressive ones, should not try to share the same territory.

Always against us

The name Comanche is a Spanish corruption of the Ute word Kohmahts, meaning enemy, stranger, or those who are always against us. Like many tribes, the Comanche called themselves simply “the people,” or Numunuh in their own language. They are an offshoot of the Shoshone, who hail from the area of today’s southern Idaho. Sometime during the 1500s, they left the mountain northwest and settled in southwest Oklahoma. There, they acquired horses from the Spanish, and began to dominate the high plains of western Oklahoma, the Texas Panhandle, and Eastern New Mexico. This vast territory was well watered and its grasslands fed the Comanche’s horses, endless herds of buffalo, and other smaller game. With the horse, the Comanche could travel rapidly on the planes, and easily kill buffalo.

In the mountain Northwest, the Comanche had been a poor, foot-bound people; with the horse they became lords of the western plains. Their population exploded. There was no census, but estimates of their numbers vary from 10 to 30 thousand. As they grew more powerful, they started raiding their neighbors. They raided the Apache and Pueblo in Arizona and New Mexico, and the Pawnee in Eastern Kansas. They traded with the Spaniards around Santa Fe but also raided settlements in Mexico and Texas. They often took captives in Mexico and ransomed them back to traders in Santa Fe for finished goods. Neither the Spanish Empire nor the Mexican Republic had the means to stop this well-organized piracy.

Despite constant raiding, some time around 1790 the Comanche made a lasting alliance with the Kiowa. Like the Comanche, the Kiowa had come from the mountain Northwest, moved into the southern plains, and acquired the horse. The Kiowa and Comanche spoke different languages, but lived in a very similar manner. The Kiowa were a much smaller tribe, and perhaps they fitted into a special niche: not worth raiding and too small to be a threat, but useful allies. This alliance between two extremely warlike people held year after year. The two tribes raided together so consistently that Comanche raids were often Comanche-and-Kiowa raids.

The Comanche came to the attention of Americans when Texas became free of Mexico. Shortly after independence, in 1838, the new republic signed its first peace treaty with the Comanche — a treaty that was probably doomed from the start. It was made with only one Comanche band, it did not define a boundary between Texas and Comanche lands, and it was never ratified by the Texas Senate. Essentially it required that the Comanche stop attacking whites — a not unreasonable demand — and some Comanche may have intended to abide by it. However, the Republic of Texas was a young, independent state with relatively wealthy white newcomers living in isolated settlements. They were irresistible targets for raiders, and the treaty was soon broken.

Comanche raids were striking examples of military precision and stealth. Raiding parties could number up to 1,500, and could move undetected across the grassland. Attacks on this scale had proven brilliantly successful against traditional Comanche targets: larger villages of mostly unarmed Mexicans or other Indians. These villages had no way to fight off the Comanche or pursue them as they retreated.

Raiders were most active during the full moon, when they could see at night. The waxing of the moon became a source of dread for Texas whites, who began to call the full moon a “Comanche moon.” When they sacked Texas farmhouses they usually killed the men and captured the youngsters and women. Comanche women often tortured and mutilated older girls and women to make them less attractive. The women also took the lead in torturing men. They might cut the skin off their feet, tie them to a horse, and make them walk behind until they collapsed and were dragged to death.

By 1840, just two years after the treaty, relations between whites and Comanche were murderous and getting worse by the day. In March, the Texas government sent Colonel Henry W. Karnes at the head of a group to meet a delegation of Comanche chiefs at the San Antonio Council House. Karnes was charged with recovering Texas captives and trying to improve relations. The Texans estimated that the Comanche held some 200 captives, and promised that their return would be taken as a gesture of goodwill.

The meeting went badly. The Comanche arrived with only one of the promised captives, a young girl whose nose had been burned off. She was badly bruised from beatings, and said she had been repeatedly gang-raped. Texan soldiers, who were already angry over the raids and the broken treaty, killed the chiefs outright. Other whites opened fire on the Comanche who were outside the courthouse.

To the Comanche, the Council House slaughter was treachery of the lowest sort. What the Texans considered savagery — raiding, torture, and slaughter of captives — were to them the normal practices of war. From this mutual incomprehension, and from the slaughter of the chiefs, the seeds of long-term hatred were planted. The Comanche never forgave the Texans. Throughout the decades they were pillaging Texas, Comanche could have raided Kansas — it was no farther away than many parts of Texas — but they saved their wrath for Texas.

The Comanche did not wait long for revenge. In early August they launched a massive attack on the coastal towns of Victoria and Linnville. In Victoria, the local militia, often called “Minutemen,” managed to drive off the attackers. They fired from inside buildings, and the Comanche, unused to city fighting, retreated. At Linnville, the raiders killed some 20 residents; the others survived only by boarding ships and moving just off shore, where they watched as the Comanche burned the town to the ground. Linnville never rebuilt, and the area is now a residential part of Calhoun County.

Linnville and Victoria are hundreds of miles from the center of Comanche territory in Oklahoma, and the attacks demonstrate the extraordinary reach and mobility the raiders enjoyed. At that time, the Comanche often hunted and camped in territory as far south as Austin. The barbed wire fence had yet to be invented, so there was little to stop them. Indeed, Texans had settled only the eastern and coastal parts of the state, so the coast was well within range of inland tribes.

The warfare that began with the council house killings and the revenge raids on Linnville and Victoria lasted until the late 1870s, and this nearly 40-year war can be divided into three stages. The first, which lasted until Texas joined the Union in 1845, pitted the Comanche against locally-organized whites supported by a Texas government that was highly sympathetic to them. The second, from 1845 until 1861, was much like the Cold War in that the federal government contained the Comanche but did not destroy their ability to make war. In the last stage of the conflict, after the Civil War, a vindictive Reconstruction government ignored bloody and repeated Comanche attacks on disarmed whites and supported the Comanche through a myriad of welfare and reform policies. Only after the post-Civil War elite was directly threatened did it take action, permanently ending the Comanche threat in 1879.

Texans strike back

Immediately after the great raids on Linnville and Victoria, the Texans called out the militia and assembled Ranger companies, and defeated the retreating Comanche force at the Battle of Plum Creek on August 14, 1840. The Comanche were slowed by the burden of their loot from Linnville, and also faced an enemy that was better armed and organized than their earlier Indian and Mexican antagonists. Since the 1830s, Texas Rangers had carried six-shooter revolvers as well as long rifles. The Comanche were still mostly armed with bows and arrows as well as lances, and usually retreated on their fast horses in the face of sustained gunfire. When the mounted Rangers could catch them, they would ride next to the Indians and inflict terrible losses with their six-shooters.

Another important ingredient in subsequent successes against the Comanche was the leadership of the dynamic and aggressive Texas president, Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar. Lamar was a Georgian who had moved to Texas to escape disappointments in his career and personal life. He fought at the Battle of San Jacinto, where the Mexican Army was defeated and Texas won independence. The Texas constitution allowed for a single presidential term in office, and Lamar was elected to succeed Sam Houston. One of the new president’s first challenges was the Comanche. As he put it, “The fierce and perfidious savages are waging upon our exposed and defenseless inhabitants, an un-provoked and cruel warfare, masacreing [sic] the women and children, and threatening the whole line of our unprotected borders with speedy desolation.”

After the victory at Plum Creek, Lamar began a policy of retaliatory raids on villages in the Comanche sanctuary in the Texas Panhandle and Oklahoma. Colonel John H. Moore, accompanied by Lipan Indian scouts, led the initial foray. The Rangers moved on an area that is now Colorado City, Texas, and the Lipans discovered a village with little security. Moore sent a detachment to cover a likely escape route, and ordered the main body of his command to attack. He caught the Comanche by surprise and killed 50 in the village. The ambush detachment killed another 80 retreating Indians. The killing was somewhat indiscriminate and included women and children. Moore’s tactics of attack and ambush were duplicated by the Rangers, and later, by the US cavalry.

(Interestingly, this was the same basic plan George Custer used at Little Big Horn in 1876. The difference was that the Sioux village was massive. The Indians also had lever-action rifles and pinned down the ambush detachment while sending a larger force to overwhelm the 7th Cavalry’s main attack. Custer never had a chance.)

Lamar saw the conflict as a race war, and made no secret of his desire to rid the state of all Indian tribes. He probably would have exterminated the Comanche if he could have, but took different measures against less war-like tribes. His administration pointedly sent no aid when diseases swept through Indian territory. He began the process that moved the Cherokee, Caddo, and Tonkowa onto reservations in Oklahoma, but once they were settled peacefully, he never harried them.

Against the Comanche, Lamar developed both defensive and offensive strategies. The Rangers’ ability to defeat large groups prevented the Comanche from forming large raiding parties, and the Minutemen in the Texas settlements — almost like local crime watches — defended against smaller raids. The system was not perfect, but the raids became smaller and less frequent. Rangers also continued to maul Comanche villages. As T. R. Fehrenbach wrote in his definitive Comanche: A History of a People, there were many retaliatory actions “no one bothered to report.”

Part of the tragedy of the war is that although the Comanche had raided for generations, they had never faced an opponent like the Texans and did not understand them. Spaniards and Mexicans were disorganized prey, and could not mount a full-scale defense. Nor did they have a militia to call out. The Comanche assumed that white men were like themselves, loosely organized bands for whom an offence against one was not an insult to all. Texans saw things differently, and united against what they considered a threat to the entire state.

Until they took on the Texans, the Comanche had always been safe from reprisal raids, so for them, the war was over when the raiding party came home. The Texans were different. Months after a raid, they would surprise an offending — or completely innocent — Comanche village and put it to the torch. Also, Comanche movements were limited by the seasons and buffalo hunts, whereas the Texans could campaign any time of year. By the end of Lamar’s administration a generation of Comanche warriors was dead. T.R. Fehrenbach estimates that from 1838 to 1840, a quarter of the braves had been killed, most of them in the actions following the Council House fight.

What saved the Comanche and kept the war alive were larger questions of geopolitics. The Texans were going broke. The country’s finances were unsound, and the Comanche campaign was just one of several conflicts Lamar had to finance. There were constant Mexican incursions, and Lamar even sent troops into Mexico at great expense. The United States was receptive to annexation, so Texas joined the Union in 1845. The expensive Ranger companies were cut back and federal troops took over their job. At first, the Army sent only infantry to forts along the frontier, and they could not stop the Comanche from moving freely over the prairies. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis formed a cavalry regiment to send to Texas, which managed to prevent some raiding. Its efforts were helped by a cholera epidemic the “Forty-niners” brought when they crossed the plains during the Gold Rush. It is estimated that the Comanche population dropped from 20,000 to 12,000 during this time.

Whites began to push the internal Texas frontier forward. The east and south were settled by then, but the north and west — where Wichita Falls and Amarillo are today — were still raw frontier. With the Comanche more or less under control, white settlers began to fill the empty parts of the state.

By 1860, the Comanche were on the defensive — reduced by plague and harried by the US Cavalry. Their final defeat would have been just a matter of time, but the Civil War changed the balance of power. The federal troops left, and Confederate forces went East. The pressure lifted, and midway through the war the Comanche started raiding again. They went back to their old ways of rape, plunder, and torture, but with a new twist. They soon found they could steal Texas cattle and trade them with Comancheros — Hispanic traders in the Rio Grande Valley — for lever-action rifles. The Texans lost the advantage in firepower they had always enjoyed. The Comanche had always been able to get a few modern weapons, but massive industrial production and increasing trade made them much easier to get.

The Texas Reconstruction government therefore inherited a new Comanche war that was blowing with a terrible fury, but did not take it seriously. The carpetbag elite was less interested in fighting Indians than in enriching itself at local expense and supporting the newly freed blacks. Things only got worse as the 1860s wore on, and T.R. Fehrenbach writes that by 1870, “long-settled regions were regressing toward depopulation. Only hundreds of settlers were being killed, but meanwhile thousands were deserting the frontier. The panic was very real.” The frontier retreated — an early form of white flight — as farmers left their properties for safer areas. Those who stayed behind turned their haciendas into fortresses. The effect was to hold back growth; the panhandle could not be settled until the 1880s. Lyndon Baines Johnson’s ancestors were among those the Comanche harried.

Even as the Comanche were murdering white homesteaders, the government attempted a sanctuary, welfare buy-off, faith-based assimilation program that is reminiscent of modern times. During the final Comanche War from 1865 to 1879, Texas whites were disarmed by the Reconstruction government, and prevented by law from retaliatory raiding into Comanche territory. They could do little more than lobby a hostile occupation government for aid — not always to much effect. Pro-Indian liberals in government as well as East Coast sentimentalists even prevented several murderous Indian chiefs from being hanged. Ironically, the attack those chiefs led was the very incident that caused the Army and federal government finally to act decisively.

More humane policy

One of the causes of federal inaction was a genuine desire to handle Indian troubles in a humane way. East of the Mississippi, Indian wars had been bloody affairs that ended with the Indians absolutely destroyed or confined. If anything, Northerners were slightly more violent than Southerners. Yankees tended to wipe out Indians and remove any survivors to small, out of-the-way reservations. In upstate New York, the Continental Army destroyed more than 40 Iroquois villages and left survivors to starve or seek aid from the British. In 1794 at the Battle of Fallen Timbers, American troops defeated an Indian force and then removed all remaining Indians from Ohio. After victories in the Midwest, whites paid the surviving Indians paltry sums for their land and sent them West with essentially no support. Abraham Lincoln’s sole experience as a soldier was a brief period of garrison duty with the Illinois Militia in the otherwise bloody Blackhawk War, in which the Sac and Fox Indians were destroyed and forced out of Illinois and Wisconsin.

In the South, the Cherokee were the source of the longest-running conflict, and held lands in Georgia long after the northeastern states had destroyed their Indians. As tensions with whites mounted, relocation became the favored solution rather than war and ad hoc expulsion, and was carried out mainly though an admittedly one-sided legal process. Cherokee removal was a relatively peaceful and fair solution to two incompatible peoples living close to each other with a long history of violence. Stand Watie, a Cherokee chief who later became a Confederate general, supported the move from Georgia to Oklahoma, and brought his band West well before the now-notorious “Trail of Tears.”

In that context it is understandable that after the Civil War, many pressure groups in the East, no longer threatened by Indians, pushed for more peaceful measures. Also backing the changes was the Office of Indian Affairs, which wanted more control over Indians at the expense of the Army. President Grant therefore tried to treat Indians as wards of government rather than independent nations, and to assimilate and civilize them rather than destroy them.

In the past, Indian wars were often sparked when a dishonest Indian Agent stole government aid to the Indians for his own profit, so in 1869, Grant charged religious groups with carrying out his new policy of turning Indians into peaceful farmers. The denomination that got the Comanche assignment was the Society of Friends, or Quakers. Quakers are one of America’s oldest and most influential founding groups. They live a life of piety and thrift, and disavow fancy dress and military action, but it may have been a mistake to pick a group religiously opposed to war in any form.

President Grant’s agent to the Comanche was Lawrie Tatum of Iowa, who had probably never seen an Indian before he answered his Church’s call and headed West. Tatum arrived at Fort Sill in 1869 and enacted a sort of Great Society program. He started schools, gave deeds of farmland to the Comanche with instructions for farming, and established a mill for grinding grain. The Comanche also got free coffee, sugar, and blankets, and lived in safety. Soldiers secured Fort Sill and the agent’s supplies, but did not interfere with Comanche activity or take to the field. Quakers would not use the military to keep the Comanche on their reservation and avoid war.

Tatum worked hard to teach the Comanche to be civilized farmers but was defeated by circumstances. The Comanche culture’s central focus was on warfare and raiding. Wealth and status could only be acquired through war, and Quaker pacifism was too foreign to graft onto their way of life. Also, welfare handouts are always unsatisfying. The Comanche were not happy with reservation rations and it was far more rewarding to plunder Texans. The Fort Sill Reservation became a sanctuary from which they could wage war. In 1871 there were even scalpings within a short distance of Army posts. Whites had sent a capable and honest agent to deal with the Comanche and bring about peace, but the Comanche were not willing to be peaceful.

Sherman and the Comanche

Just as it is today, it was whites who lived furthest from the menace who were convinced they knew best how to handle it. In Philadelphia or New York it was easy to talk about humane Indian policies, but on the frontier, whether in Confederate or Yankee territory, sentiments were different. In Minnesota in 1862, Sioux Indians attacked whites, killing hundreds. Many whites were fresh from northern Europe or descended from the very liberal Puritan and Quaker colonists. Yet they rallied and pushed the Sioux out of the state.

In Colorado in 1864, Methodist minister and volunteer army officer John Chivington, a fervent abolitionist, led a force of mostly settler militia against a group of Cheyenne after a series of murderous raids. His militia massacred Indians without compunction but his force also included a few regulars from the East who were appalled by the killing and raised a stink. Chivington also made a bad mistake: He attacked a peaceful band of Indians, not the hostile Dog Soldiers, an out-of-control offshoot of the Cheyenne, who were actually doing the raiding.

Also in 1864 an Army unit under Kit Carson fought the Comanche at the Battle of Adobe Walls, in Hutchinson County, Texas. The Indians surrounded the force but were held off with two mountain howitzers. The cannon were decisive. Carson’s men were outnumbered nearly ten to one, but killed nearly 100 Indians for a loss of six whites.

Texans therefore eventually got help from people who knew Indians first hand. Help arrived, ironically, in the form of William T. Sherman, who never had much faith in Grant’s Indian policy. In 1871 he toured Texas to inspect damage from Comanche raids, and had a near encounter with Indians that had an effect on policy. A group of braves led by Set-tainte, Set-tank, and Big Tree attacked a wagon convoy of Army supplies that passed just minutes behind Sherman’s lightly guarded inspection tour. The dozen men on the convoy fought back, but seven were killed, scalped, and mutilated. One man died after being tied upside down to a wagon wheel with a fire set under his head.

Sherman was shaken by this close call, and sent out the cavalry under Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie to investigate. With information from Agent Tatum, Mackenzie cornered the three ringleaders. Set-tank died resisting arrest, but the other two were sent back to Texas for trial.

Set-tainte and Big Tree were sentenced to death, but not executed. The trial became a circus, with the two Indians at the center of a political struggle they must have found bewildering. As T.R Fehrenbach explains, “There was much popular sentiment in the East against hanging the aborigines; more important, the Indian Bureau and Department of the Interior strongly resented the army’s interference in Indian affairs.” President Grant wired the Reconstruction governor Edmond J. Davis and asked him to commute the sentences to life in prison. Davis did so. Eventually the two were released after serving less than a year. Texans were outraged. Even Quaker Tatum, who by this time was thoroughly disillusioned with the peace policy, was indignant.

Although President Grant had pushed for a pardon, he reconsidered the peace policy and quietly let Colonel Mackenzie take the field. Mackenzie brought along Gatling guns, which gave his men a real edge over larger forces. (Rapid-fire weapons were rarely used against mass charges of Indians — they were too smart to try that — but having them meant Mackenzie’s men rarely had to face such charges. Things might have turned out differently for Custer if he had taken Gatling guns.)

Mackenzie drove ruthlessly into Comanche territory. He was a hard man, who pursued Indians wherever they fled — even into Mexico — and his men certainly killed women and children. One of his harshest tactics was to capture any Indians he could — women, children, elders — and hold them hostage. This meant Comanche war parties were forced to move with their entire villages, lest their families wind up in prison camp or dead from a trigger-happy trooper. The Comanche had even more to fear from the militia. Local men who may have known people killed in raids were invariably more vengeful than professional soldiers.

This policy of interning non-combatant Indians was part of one of the last full-scale campaigns against the Comanche, starting in August 1874, when Mackenzie pursued a force led by Chief Quanah Parker into the Llano Estacado of the Southern Plains. In late September, Mackenzie’s men captured a New Mexican Comanchero trader and made him talk by stretching him over a wagon wheel. He revealed the location of a large Comanche village in a canyon. Mackenzie’s men rode all night and stormed the canyon, capturing the horses, food stores, and teepees. The braves, always excellent fighters, held off the army until the women and children climbed out of the canyon, but Mackenzie burned their supplies and killed their horses. Over the next several days, he pursued and defeated the hungry, foot-bound Comanche. Many braves surrendered and returned to the reservation.

These tactics greatly reduced the Indian menace by the end of 1875, but the Comanche faced yet another threat. The expanding railroads brought whites armed with new buffalo guns onto the prairie to hunt the buffalo for their skins. The result was a slaughter that nearly wiped out the great herds on which the Comanche had depended for generations. The hunters themselves were dangerous; one group defeated a larger force of Comanche with their excellent rifles in 1874, at the Second Battle of Adobe Walls. Constantly pursued by the Army, starving for want of game, by 1879 the Comanche were a beaten people and never again threatened Texas. From a possible high of 30,000 at the start of the 19th century, the Comanche were reduced to roughly 1,500 by 1878. A once-proud people finally submitted permanently to the reservation.

The Comanche War is now history, its many tales preserved in movies and books. No Texan now living ever feared a Comanche moon. Today, tribal conflict takes different forms, and it is incursions from the South that are pushing back the white frontier. Clashes are not so sharp as those in the 19th century, but the outcome is no different. The destiny of Texas is being decided through immigration and demographics rather than armed conflict, but the questions remain the same: who will populate and who will rule? Earlier Americans understood what was at stake; today’s Americans have been numbed into acquiescence.

Duncan Hengest served as a company-grade field artillery officer in the United States, Korea, and Iraq. He can be reached at d.hengest@yahoo.com.

The Only Good Indian . . .Many people think Sherman said that “the only good Indian is a dead Indian,” but he always denied it. It may well be that the phrase expressed his true sentiments, however, since he waged harsh war on Indians, allowed diseases to take their course among them, and encouraged the slaughter of the buffalo on which the Indians depended. The originator of the phrase seems to have been Montana Congressman James Michael Cavanaugh (1823-1879), who opposed Grant’s Indian policy. He was originally from Massachusetts, but made a career as a lawyer/pioneer in Minnesota, Colorado, and Montana at the height of the Indian troubles. He made the following remarks during a debate on an Indian Appropriation Bill that took place on May 28, 1868, in the House of Representatives:

|

| BOOK REVIEW |

|---|

Whiting Out White People

A black woman tells us what we must think.

Nell Irvin Painter, The History of White People, W.W. Norton, 2010, 496 pp., $27.95.

Nell Painter, a professor of American history at Princeton, has written something she calls The History of White People, but it is not really history. The Greek word historia means an inquiry or narrative into the events of the past. Instead, Prof. Painter has written a deconstruction of what she considers the false and oppressive “social construct” of race, which was invented “by dominant peoples to justify their domination of others.” She starts with ancient Europe, where she asserts there was no such thing as white people because no one thought in terms of race. She admits that some people had lighter skin than others, but that no one attached any meaning to it. Then she skips to the Enlightenment, where, she claims, race and whiteness were invented, and devotes most of the book to what she considers the crackpot science of race that flourished from about 1780 to 1930.

Professor Painter also denies that there is any such thing as white history, white culture, or white civilization. “Whiteness,” she tells us, “is merely a “category of non-blackness,” “the leavings of what is not black” — in other words, pure negation. Prof. Painter’s goal is to make whites a non-people by denying their existence and erasing their history. Needless to say, The History of White People has been respectfully reviewed rather than denounced as a breathtaking dismissal of an entire people.

Prof. Painter writes that her book belongs to the new field of “white studies,” which was established in the 1990s. It is more cult than academic discipline, and is based on denial of the obvious. “Today,” Prof. Painter announces, “biologists and geneticists . . . no longer believe in the physical existence of races — though they recognize the continuing power of racism (the belief that races exist, and that some are better than others).” She also writes that “each person shares 99.9 percent of the genetic material of every other human being,” and dismisses skin color as a superficial adaptation to the strength of the sun (for a more sensible view see, for example, “Race is a Myth?” AR, Dec. 2000 and “How Myths are Maintained,” AR, Jan. 2004). Having disposed of both science and common sense in just a few sentences, she warns that we must retain the “category” of race only long enough “to strike down patterns of discrimination.” Race is a myth but “racism” is real.

The ancients

Prof. Painter begins her “history” with the ancient world, “thousands of years before the invention of the concept of race.” “Ancient Greeks did not think in terms of race,” she says with authority. Nor did the Romans. They could not have been white because “neither the idea of race nor the idea of ‘white’ people had been invented.” She complains that “not a few Westerners have attempted to racialize antiquity, making ancient history into white race history.”

Prof. Painter is wrong; the concept of race is of ancient lineage. Both the Greeks and Romans had several words equivalent to our word, “race.” The word “ethnic,” meaning origin by birth or descent rather than by present nationality, is derived from the ancient Greek ethnos, which meant the same thing in ancient times. If she read ancient literature Prof. Painter would find that classical scholars translate ethnos as people, nation, or race, depending on context.

Nationality in the ancient world was defined by birth and descent. Thus, when the Hellenic historian Herodotus, the father of history, wrote of the Ellenikon (Hellenic) ethnos, acceptable translations would be Greek people, Greek nation, or Greek race. During the Persian invasion of 480-479 BC, the Athenians assured their Spartan allies that they would not betray fellow Greeks: “we are one in blood and one in language, and we worship the same gods.” Plato observed that “the Hellenic race is united by ties of blood and friendship.”

The Greeks were not unified politically until the time of Alexander (356-323 BC). Before that, their city states often fought each other, but they always recognized that, whatever their city or tribe, they belonged to the same nation or race. They called non-Greeks barbaroi, and resident foreigners metics. The latter were not normally eligible for citizenship. When Pericles (495-429 BC), the Athenian statesman and democrat, proposed a law to deny citizenship to anyone not born of both an Athenian mother and father it easily passed the assembly and became law.

The Greeks also drew clear ethnic distinctions between peoples. Homer used the figurative phrase “sun-burnt races” for brown-skinned Asiatics [and Africans] because Greeks and Europeans were lighter-skinned. Aristotle believed that “barbarians were more servile in character than Hellenes, and Asiatics more so than Europeans, for Asiatics submit without murmuring to despotic government.” Aristotle urged his pupil Alexander to maintain sharp distinctions between Greeks and their eastern enemies, and to treat conquered peoples “like plants and animals.” Prof. Painter quotes the Greek physician Hippocrates, who noted of the Scythians that “it is the cold which burns their white skin and turns it ruddy.” Prof. Painter does not seem to have noticed the words “white skin” in this passage.

As for the Romans, there is even clearer evidence that they thought in terms of common descent and physical differences. Their words genus and generis were almost an exact equivalent to our word “race.” Cassell’s Latin Dictionary defines them as meaning “race, stock, family,” also “birth, descent, origin,” and in its broadest sense, “kind.” Our word genocide comes from it. Romans had a related word, gens, gentis, which meant “clan,” but more generally, “people, tribe, nation.” It was derived from the verb gigno or geno, meaning “to beget, bear, bring forth.” The words natio and nationis meant “being born, birth,” but could also mean “tribe, race, or people.” Natio was the Roman goddess of birth, and our word nation comes from her name.

Clearly the Romans, like the Greeks, regarded a nation as a group with a common ancestry, in other words an ethnic group or race. The Roman historian Suetonius recorded that “[Emperor] Augustus thought it very important not to let the native Roman stock be tainted with foreign or servile blood, and was therefore unwilling to create new Roman citizens, or permit the manumission of more than a limited number of slaves.” The poet Juvenal railed against “Easterners” (Egyptians, Syrians, Jews) who were flooding into Rome, complaining that the Orontes, a river in Syria, “has poured its sewage into our native Tiber.” He called one upstart Egyptian “silt washed down by the Nile.” Romans never spoke of fellow Europeans — Thracians, Germans, Gauls, Iberians — in such insulting terms, except for the Greeks, for whom they appear to have held some special enmity. Juvenal even warned one Roman administrator that while it was safe to plunder the eastern provinces, not so the western: “But steer clear of rugged Spain, give a very wide berth to Gaul and the coast of Illyria.”

The Romans were clearly struck by the physical appearance of the Celtic and Germanic tribes to their north. Prof. Painter does not include a single physical description of the Gauls by a Roman, but there are many. Diodorus Sicilus (1st century BC) described “the Gauls as tall of body, with rippling muscles, and white of skin, and their hair is blond . . .” Ammianus Marcellinus, the late imperial Roman historian (4th century AD), wrote that “almost all Gauls are tall and fair-skinned with reddish hair.” Virgil described the Gauls who sacked Rome in 390 BC as having “golden hair, striped cloaks, white necks entwined with gold.” The Roman historian Cassius Dio (c. 150-c. 230 AD) described Queen Boudicca, who led the Gallic revolt against Roman rule in 61 AD, as being tall with long-flowing “tawny hair.” Prof. Painter does manage to quote Tacitus, who described the Germans as “tall” with “fierce blue eyes and red hair.” (Tacitus used the word rutilus, which meant “red, golden, auburn.”)

It is clear, therefore, that even if they did not use the word, the Romans thought of their northern neighbors as white, and some suffered from what might be called “blond envy.” Having lost some of the fair features of their ancestors, later Romans wanted to look more like the Gauls and Germans. The Christian author Tertullian (160-225 AD) complained that “some women dye their hair blond by using saffron. They are even ashamed of their country, sorry that they were not born in Germany or in Gaul.” Juvenal records that the Emperor Claudius’ wife Messalina kept her “black hair hidden under an ash-blonde wig.” Prof. Painter claims that the ideal of white beauty arose as part of the Eastern European slave trade. She is off by about 1,500 years.

The Romans not only noticed physical differences, they thought of them in racial terms. When Tacitus found the same physical features (“red hair and tall stature”) among the people of Caledonia (Scotland), he assumed that they were of “Germanic origin,” meaning that they belonged to the same race. When he noticed that the Silures living nearby had “swarthy faces and curly hair,” he assumed they were of Iberian origin. Iberians had the same features and could have sailed from Spain to Britain. Tacitus was not sure whether heredity or climate was the stronger influence on physical appearance, but Prof. Painter assures us that the ancients thought it was all due to climate.

Prof. Painter mentions the peoples of northern and western Europe — whom the Greeks knew as Keltoi and Skythai and the Romans as Celtae, Galli, and Germani — only to tell us that they did not think of themselves as white. “Rather than as ‘white’ people, northern Europeans were known by vague tribal names: Scythians and Celts, then Gauls and Germani.” Prof. Painter is wrong. Those were national, not tribal names. The Germans knew themselves by such tribal names as Marsi, Suebi, or Alemanni. It was the Gauls, and then the Romans, who gave them the national name Germani. Likewise, the Celts called themselves by their tribal names, such as the Helvetii of what is now Switzerland, and the Iceni of eastern Britain, but they were aware that they belonged to a family of tribes related by kinship, religion, language, and mores.

Like all good anti-racists, Prof. Painter thinks “pure racial ancestry” is “nonsense.” Yet how do we explain the close resemblance between Gauls and Germans, on the one hand, and their descendants in those places that have seen little non-white immigration: Iceland, Scandinavia, Scotland, Nova Scotia, New Zealand? These people kept their physical characteristics because generations of whites married other whites. Even the Romans assumed that Nordics could not mix with darker people without losing their fair features. Tacitus concluded that the blond people of Germania were “a pure race unmixed by intermarriage with other races,” partly because of their northern isolation but also because they looked so similar to each other. Adamantius, the Alexandrian physician (4th century AD), made the same point about the Greeks of his time: wherever the Hellenic race “has been kept pure” it retained the light features of its ancestors.

Prof. Painter confuses the recessive traits of whites with some kind of natural variability. “Anyone in a mixed-race family knows of the impermanence of parental skin color, for the sex act immediately affects the very next generation.” That simply proves what she denies: features that have persisted for millennia can disappear in a single generation when whites marry outside their race. Whites — but apparently only whites — are evil if they take pride in their appearance and want to perpetuate it in future generations: “Nowadays, only white supremacists and Nazis fetishize white racial purity.”

The modern era

Prof. Painter devotes many chapters to “scientific racism,” the systematic study of anthropological differences that began in the late 18th century. “Scientific racism” in this context is an anachronism because the word “racism” did not appear until the 1930s and had no ancient, medieval, or early modern counterpart. The concept behind it — that it is morally wrong to discriminate on the basis of race — is a mid-20th century invention.

Because she has decreed that there is no such thing as race, Prof. Painter regards any attempt to study it as pseudo-science. She explains that 19th-century “European anthropologists were typically both provincial and arrogant. They operated from two basic assumptions: the natural superiority of white peoples and the infallibility of modern science.” It is she, however, who is guided by unproven articles of faith: the non-existence of race, the equality of all people, and the decisive power of environment. Her sole criterion for judging earlier anthropologists is the extent to which they anticipate her globalist views.

The modern use of the word “race” to describe the divisions of mankind dates to about 1775, with the publication of Johann Friedrich Blumenbach’s On the Natural Variety of Mankind. Blumenbach, a German anthropologist, was the first to classify whites as Caucasian. In the 1795 edition of his book, he proposed five racial types: Caucasian (white); Malayan (brown); Mongolian (yellow); Negro (black); American (red). Prof. Painter likes him because he believed that climate determined skin color, and because he classified so many non-Europeans — North Africans, Middle Easterners, South Asians — as Caucasian and therefore white. Blumenbach’s expansive classification of whiteness was never generally accepted; most people simply do not think of Tunisians and Frenchmen as the same race.

Prof. Painter also likes Franz Boas (1858-1942), the influential Columbia anthropologist who believed that environment, not genes, “shaped people’s bodies and psyches.” He claimed to have conducted an inter-generational study that found that the longer eastern and southern European immigrant women lived in America, the more their children’s head shapes came to resemble those of the northern European founding stock. “These findings were nothing short of revolutionary,” writes Prof. Painter. In fact, a reexamination of the data found they were nothing short of bogus.

Prof. Painter devotes three chapters to Ralph Waldo Emerson, whom she despises for the pride he had in his own people. Emerson was “the most prestigious intellectual in the United States,” and thus gave further respectability and weight to the racialism of his time. Emerson may have been a progressive, a pantheist, and an antislavery man, but he also believed in the reality of race, the hierarchy of race, and the superiority of Anglo-Saxons.

Emerson believed that race was destiny. In other words, that the genetic endowments of a people largely determined their fate. Some races were capable of great things, others (Africans, for instance) were not. Environment, he thought, had little influence. “If the race is good, so is the place.” In his view, no race was greater than the English, and he considered his fellow New Englanders to be of pure English descent. In his widely read and celebrated English Traits (1856), he argued that the English were derived from the Celts, the Saxons, and the Northmen. All three were great races, and this union had created a people of genius, unsurpassed in beauty, valor, energy, and intellect. How else had this island nation conquered or settled most of the world, contributed so much to science, and produced so much great literature? The Saxons he considered to belong to the southern, Germanic branch of the formidable “Scandinavian race,” the Northmen (Norwegians, Swedes, Danes) to the northern branch. “Both branches . . . are distinguished for beauty.” It is easy to see why Professor Painter thinks Emerson was a dangerous figure.

As for Alexis de Tocqueville, Prof. Painter approvingly summarizes his critical comments about American slavery, but claims that he “minimizes one of the core issues in American politics and culture.” Not so. Tocqueville devoted a chapter of Democracy in America to race. Far from minimizing it he speculated that “the most formidable evil threatening the future of the United States is the presence of the blacks on their soil.” Tocqueville realized that even if slavery were abolished, racial differences that were “physical and permanent” would remain. Freed blacks would be jealous and resentful of their former masters and ashamed of their servile past. “Memories of slavery disgrace the race, and race perpetuates memories of slavery.”

Whites, on the other hand, would want nothing to do with former slaves. Tocqueville noticed that “race prejudice seems stronger in those states that have abolished slavery than in those where it still exists,” and thought one reason was the fear of miscegenation. “Of all Europeans,” he wrote, “the English have least mingled their blood with that of the Negroes.” Why not? “The white man in the United States is proud of his race and proud of himself.” As a result, “the freer the whites in America are, the more they will seek to isolate themselves.” Only a “despot subjecting the Americans and their former slaves beneath the same yoke” could “force the races to mingle,” Tocqueville wrote, but “while American democracy remains at the head of affairs, no one would dare any such thing.” Perhaps Tocqueville was too prescient for Prof. Painter’s liking.

Prof. Painter points out that many of the most important American racialist thinkers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries were from old and distinguished New England families. Thus, American Nordicist Madison Grant was a “quintessential patrician racist.” Grant wrote the bestselling and widely influential The Passing of the Great Race (1916). He was a leading conservationist and was friends with Theodore Roosevelt, who read and praised his work. Prof. Painter finds this quite shocking.

Another important racial thinker, whose work Prof. Painter dismisses as a “frenzied contribution to white race theory,” was Lothrop Stoddard (1883-1950). Stoddard, who was a protégé of Grant, had a Ph.D. in history from Harvard, and wrote The Rising Tide of Color in 1920. It sold well and even had a cover blurb from Warren G. Harding, who was elected President of the United States that fall. Prof. Painter does not discuss the contents of the book — again, it was perhaps too prescient. Stoddard warned his white brethren of the dangers of racial infighting (he opposed both world wars), and predicted the breakup of the European colonial empires. He foresaw the rise of fundamentalist Islam, the emergence of brown nationalism, as well as mass migration of non-whites into white homelands.

Of course, for Prof. Painter, anyone past or present who thinks whites are worth preserving as a distinct people with a distinct destiny is a vicious bigot, and if she has her way, whites will be displaced and outbred. The preposterous idea that race does not exist is only the most recent argument meant to overcome what faint resistance whites may yet have to oblivion. After all, if there is no such thing as race and we are 99.9 percent identical, we are only being replaced by ourselves.

Prof. Painter is black, and it is rare for blacks to claim to believe that race is a myth. Most blacks have such a vivid sense of race that they see this whites-only-believe-it foolishness for what it is. Everybody knows races exist, that they have distinct features, and that when members of different races mate they produce hybrids. What else is there to know? There is very little prattle from blacks about race as a “social construct,” so perhaps it is fitting that Prof. Painter, who claims she wants to obliterate race, mouths trendy nonsense that usually fools only whites.

Blacks will largely ignore her book, but The History of White People was the subject of the main review in the New York Times Book Review of March 28, 2010, and it was treated respectfully in The New Yorker of April 12, 2010. However, even The New Yorker found “something reductive” in Prof. Painter’s insistence “that whiteness . . . isn’t real.” “Perhaps it’s time we start viewing it,” the article went on, “as the slow birth of a people.” Substitute rebirth for birth and The New Yorker is on to something. As for “white studies,” it is a redundant field. We already have it. It’s called European history and Western Civilization.

Mr. Sims is an historian and a native of Kentucky.

| IN THE NEWS |

|---|

O Tempora, O Mores!

White-Hispanic Divide

According to a recent NBC/MSNBC/Telemundo poll, Arizona’s new law cracking down on illegal immigrants enjoys the support of 61 percent of Americans. Among whites, however, 70 percent support the law. Most Hispanics — 58 percent — oppose it, with only about one third in favor.

The Arizona law is just one issue that divides whites and Hispanics. Sixty-eight percent of Hispanics think immigration strengthens America, while only 43 percent of whites do. President Obama’s job approval rating among whites has dropped to 38 percent, while most Hispanics — 68 percent — support him. A narrow majority of whites prefer the Republican Party over the Democratic Party (37 percent vs. 34 percent), while Hispanics favor the Democrats over the GOP (54 percent vs. 22 percent). Hispanics also think Democrats are better than Republicans at protecting the interests of minorities (58 percent vs. 11 percent), boosting the economy (46 percent vs. 20 percent), dealing with immigration (37 percent vs.12 percent), and promoting strong moral values (33 percent vs. 23 percent). The only thing Hispanics think Republicans do better than Democrats is patrol the US-Mexico border (31 vs. 20 percent).

Bill McInturff, one of the pollsters who ran the survey, has noticed the obvious: “The gap between whites and Hispanic Americans is substantial.” [Mark Murray, On Immigration, Racial Divide Runs Deep, MSNBC, May 26, 2010.]

Californians vs. Arizona

Manuel Lozano, mayor of Baldwin Park, California, doesn’t like the new Arizona law. He calls it “racial profiling,” and urged his city council to get tough on Arizona. In May, the council passed an ordinance boycotting Arizona financially (although it isn’t known how much business, if any, the Los Angeles suburb does with the neighboring state), and Mr. Lozano organized a pro-immigration rally on a Saturday morning in a downtown park. The city paid for a stage and a sound system, but the mayor canceled the rally just a few minutes after it was supposed to start — because no one showed up. Mr. Lozano says he pulled the plug when he realized there were too many other activities scheduled for that day. He insists that the absence of supporters does not mean residents don’t like the Arizona boycott, and promises to reschedule. [Maria Ines Zamudio, Baldwin Park Pro-immigration Rally Canceled after No One Showed Up, Whittier Daily News, May 22, 2010.]

A recent poll by the Los Angeles Times and the University of Southern California found that 50 percent of Californians support the Arizona law, while 43 percent oppose it. National polls find that 60 to 70 percent of Americans support the law. What accounts for California’s tepid numbers? The large number of Hispanics. Majorities of California whites (58 percent) and residents over 45 (57 percent) support the law, while Hispanics (71 percent) and younger Californians (58 percent) strongly oppose it.

Two typical views: Gina Bonecutter, 39, of Laguna Hills, favors the Arizona law. “What I’m seeing today is immigrants coming here, wanting us to become like Mexico, instead of wanting to become American,” she says. Daisy Vidal of Banning, a 23-year-old college student and child of immigrants, thinks “there should be some type of pathway to citizenship,” adding that “this whole country was started by immigrants.” [Seema Mehta, Californians Split on Arizona’s Illegal Immigration Crackdown, Los Angeles Times, May 31, 2010.]

On June 1, Los Angeles County joined San Francisco, Oakland, Los Angeles, San Diego and several other California cities in an economic boycott of the Grand Canyon State. The county will review the $26 million in contracts it has with Arizona companies, and cancel as many as it can. The Board of Supervisors voted 3 to 2 in favor of the measure. [LA County Boycotts Arizona over Immigration Law, AP, June 1, 2010.]

Arizonans vs. California

After the San Diego city council voted in May to boycott Arizona, Arizonans started canceling trips and vacations to the city. With an average of two million Arizonans visiting San Diego each year, tourism industry officials are worried. “We’re in a very tough environment already because of everything else going on, and we don’t need another negative impact to our industry,” says tourism official Joe Terzi. Hotel managers are urging angry Arizonans to consider the boycott a “symbolic” matter of local politics.

San Diego school board president Sheila Jackson, whose group also voted to boycott Arizona, says its tough luck for the tourism industry. “It’s sad that people would cancel their plans to come here in reaction to that, but I still think we did the right thing.” [San Diego Faces Own Medicine as Arizona Residents Cancel Travel Following Boycott of State, Fox News, May 17, 2010.]

After Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa announced his city would boycott Arizona, Arizona Corporation Commissioner Gary Pierce, who sits on the board that regulates Arizona’s electricity generating plants, sent him a letter reminding him that Arizona supplies a quarter of LA’s electricity. “If an economic boycott is truly what you desire, I will be happy to encourage Arizona utilities to renegotiate your power agreements so Los Angeles no longer receives any power from Arizona-based generation,” he wrote, adding that if the LA city council “lacks the strength of its convictions to turn off the lights in Los Angeles and boycott Arizona power, please reconsider the wisdom of attempting to harm Arizona’s economy.” [Ryan Randazzo, Arizona Electricity Regulator Pokes Los Angeles Over Boycott Call, Arizona Republic, May 20, 2010.]

Sign of the Times

In the interest of “fairness” and “self-esteem,” a children’s soccer league in Ottawa, Canada has decided that any team that wins a game by more than five points will automatically lose by default. The league used to operate under a five-point “mercy rule” that did not count more than a five-point score difference, so the most a team could lose by was five points. Bruce Cappon, whose 17-year-old son plays in the league, calls the new rule “ludicrous.” “Heaven forbid when these kids get into the real world,” he says. “They won’t be prepared to deal with the competition out there.”

League director Sean Cale defends the rule, which he says was suggested by “involved parents” to ensure “sportsmanship” and make games more “fair.” He blames the controversy on a small number of trouble-making parents. “The registration fee does not give a parent the right to insult or belittle the organization,” he huffs. “It gives you a uniform, it gives you a team.” [Terrine Friday, Win a Soccer Game by More Than Five Points and You Lose, Ottawa League Says, National Post, June 1, 2010.]

For Blacks Only

Black Georgia congressman Hank Johnson, notorious for suggesting during a congressional hearing that the island of Guam could “tip over and capsize” if too many troops were stationed there, is facing stiff competition for his seat. On June 2, he and three opponents took part in a debate sponsored by Newsmakers Live, a black media organization claiming to have a “global urbane perspective.” Several of Mr. Johnson’s opponents are white, but they are apparently not urbane enough; Newsmakers Live did not invite them. When white Republican Liz Carter called to get an invitation, the forum’s moderator, Maynard Eaton, told her it was for black candidates only. He said she was welcome to sit in the audience, but not participate. “What happened to diversity?” she asks.

Miss Carter’s chances of winning the 4th district seat are slim. The electorate is overwhelmingly black, and the seat was previously held by the conspiracy-minded Cynthia McKinney. [Alex Pappas, White Congressional Candidate Wants to Participate in Forum, But is Told She Can’t Because She’s Not Black, Daily Caller, June 2, 2010.]

Not Safe Anymore

Atlanta’s Piedmont Park used to be a safe place for whites to take their families for summer entertainment. Not anymore. On June 3, a large crowd of mostly young people gathered for “Screen on the Green,” to watch the movie “Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen.” The screening was stopped 20 minutes early, ostensibly for “technical reasons.” The real reason was that blacks got so violent sponsors and police decided to send the crowd home.

First, a fight broke out among a group of girls, and before long, boys began fighting. “Just as things started to settle back down, a few gunshots rang out and the crowd started trampling the area trying to flee the scene,” recalls Ron Sweatland, who was at the park with his wife. “It was an absolute mob scene,” says another man who was at the park, “from the Chick-fil-A girls getting mobbed trying to hand out free sandwiches to the complete lack of respect for the people watching the movie.”

As he was leaving, Mr. Sweatland saw teenagers throwing rocks at cars, some of which broke windows. Children in the crowd were frightened and crying. “I can remember a time when Screen on the Green was great family fun and we always looked forward to going,” he says. “I think this will be our last time.”

Many blacks attacked whites. Twenty-six-year-old Josh Hice was driving by the park in an open-top Jeep. “There was a car stopped in front of me and a car stopped behind me, and there was this crowd of about 30 high school kids parading down the street,” he explains. A girl came spat in his face and a teenaged boy punched him. “It split my lip, then they start climbing all over my Jeep, and I turn around and my buddy is getting punched in the face and has blood pouring out of his nose. It was ridiculous. We were definitely victims of a hate crime.”

Atlanta city councilman Alex Wan, who represents the area, says the troubles were “not the norm,” and were “caused by a small group of young kids looking to cause trouble . . . I hope we can make a few adjustments and come back to having great events in this part of town, because it is so popular with the neighborhood and the city.” [Mike Morris, Police Reviewing Security at Screen on the Green, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, June 4, 2010.]

Owning the Bee

The National Spelling Bee has come a long way from its origins in 1925. The first was organized by the Louisville Courier-Journal and featured nine contestants. The 83rd took place in Washington, DC, June 2 through 4 and featured 274 contestants, ranging in age from eight to fifteen. The bee was broadcast on live national television, with the championship finals in prime time on ABC.

This year’s winner was a 14-year-old girl from North Royalton, Ohio, named Anamika Veeramani. Miss Veeramani, who won by spelling the medical term “stromuhr”(an instrument used to measure the amount and speed of blood flow through an artery), is of Asian Indian descent, as was the runner-up, 13-year-old Shantanu Srivatsa of West Fargo, North Dakota. In fact, Indians, who make up less than 1 percent of the US population, have won three straight National Spelling Bee titles, and eight of the past twelve. The first Indian winner, Nupur Lala, took the title in 1999, and was featured in an Academy Award-nominated documentary, “Spellbound.” No one knows why Indians are so good at spelling. Many, such as 2008 champion Kavya Shivashankar, say they were inspired by the first Indian to win the title.

The father of this year’s champion thinks it has more to do with discipline. “This has been her dream for a very, very long time. It’s been a family dream, too,” he says, adding that his daughter studied as many as 16 hours on some days. “I think it has to do with an emphasis on education.” Miss Veeramani, who won $40,000, hopes to go to Harvard and become a cardiovascular surgeon. [Lauren Sausser, Spelling Bee Winner Part of Indian-American Streak, AP, June 5, 2010.]

Fined in France

Brice Hortefeux is the interior minister of France, a senior member of President Nicholas Sarkozy’s governing UMP party, and a personal friend and confidant of the president. Last September, Mr. Hortefeux was joking with a small group of party activists, including one of Arab descent. The banter was recorded, and an activist can be heard saying of the Arab, “Amin is a Catholic. He eats pork and drinks alcohol,” to which Mr. Hortefeux replies, “Ah, well that won’t do at all. He doesn’t match the prototype.” A woman then says, “He is one of us . . . he is our little Arab.” Then Mr. Hortefeux says, “We always need one. It’s when there are lots of them that there are problems.”

When the tape became public, the media called Mr. Hortefeux a “racist.” The opposition Social Democrats said his remarks were “shameful and unspeakable,” and demanded his resignation. Although the Arab defended him, prosecutors still charged Mr. Hortefeux with “racism.” In early June, a French court declared his remarks “incontestably offensive, if not contemptuous,” and found him guilty on a civil charge of “racial insult.” The court spared him a criminal conviction because it found that he had not intended his comments to be heard in public. Nevertheless, it ordered Mr. Hortefeux to pay a 750 euro fine ($900) and to pay 2,000 euros to an anti-racism group. A lawyer for Mr. Hortefeux says he will appeal. [French Minister Hortefeux Fined for Racism, BBC News, June 4, 2010.]

Miscegenation on the Rise

Credit Image: Robin Rayne Nelson / ZUMAPRESS.com

According to a new report from the Pew Research Center, in 2008, one of every seven marriages — 15 percent — crossed racial lines. That is six times the intermarriage rate of 1960. Of all 3.8 million adults who married in 2008, 31 percent of Asians, 26 percent of Hispanics, 16 percent of blacks and 9 percent of whites married a person of a different race. Demographer Jeffrey M. Passel, the lead author of the report, attributes the change to a weakening of “long-standing cultural taboos,” along with increased immigration from Asia and Latin America.

The report found that white-Hispanic marriages were the most common mixed-race pairing, accounting for 41 percent of the 280,000 mixed-race marriages in 2008. Black-white pairings remain the least common — about 1.6 percent of all marriages, but up sharply from the 0.1 percent in 1960, when such marriages were illegal in many states. Among all married blacks in 2008, 13 percent of men and 6 percent of women had a non-black spouse. Among US-born Asians, on the other hand, half married non-Asians.

Mr. Passel says that one surprising finding is that 22 percent of black men marry women who are not black. This figure is up from 15.7 percent in 2000 and 7.9 percent in 1980. Only about 9 percent of black women marry non-blacks, so the black male outmarriage rate is cutting into marriage prospects for black women. “When you add in the prison population,” says Prof. Steven Ruggles, director of the Minnesota Population Center, “it pretty well explains the extraordinarily low marriage rates of black women.”

Mr. Passel believes increased intermarriage — and its reproductive by-products — are redefining the way Americans see race. “The lines dividing these groups are getting blurrier and blurrier,” he says. Just before the 2010 census, estimates put the total US mixed race population at 5.2 million, a 32 percent increase over 2000.

Not everyone sees a happily-blended, post-racial future. Because relatively few blacks and whites intermarry, some say the black-white divide will persist. “Children of white-Asian and white-Hispanic parents will have no problems calling themselves white, if that’s their choice,” says Andrew Hacker, a professor of political science at Queens College in New York and author of the 1992 book, Two Nations: Black and White, Separate, Hostile, Unequal. “But offspring of black and another ethnic parent won’t have that option. They’ll be black because that’s the way they’re seen.” [Mary Brophy Marcus, Report: Marriages Mix Races or Ethnicities More Than Ever, USA Today, June 4, 2010. Sam Roberts, Black Women See Fewer Black Men at the Altar, New York Times, June 4, 2010.]

Betting on Asians

Asians, particularly Chinese, love to gamble. Tim Fong, a psychiatry professor and co-director of the gambling studies program at the University of California-Los Angeles, says gambling appeals to Asian beliefs in predestination and fate. Whatever the cause, casino operators have been cashing in for years. After the MGM Grand casino opened in Las Vegas in 1993, officials redesigned the lion’s-mouth entrance after learning that some Asian gamblers thought it was bad luck to walk through the mouth of an animal. Many casino elevators don’t have buttons for the fourth floor because four is an unlucky number for some Asians.

There are more than half a million Asian gamblers in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States, and gambling joints are trying hard to lure them. They have hired directors of “Asian-American player development” to beat the bushes for more gamblers, expanded restaurants and menus, and are running Asian-language ads in newspapers and on billboards. Asians don’t like slot machines, so operators in Pennsylvania, Delaware, and West Virginia are adding baccarat and pai gow, a version of poker based on an ancient Chinese tile game.

Some Asians say casinos are taking advantage of a cultural weakness. “These businesses are predatory,” says Ellen Somekawa, executive director of Asian Americans United, a Philadelphia pressure group that has been fighting plans to build a casino near the city’s Chinatown. “We’re concerned that it will have a harmful effect on the Asian-American community and all the communities in Philadelphia.” [Charles Town, Other Casinos Target Asian-American Market, AP, June 1, 2010.]

As the New Century Foundation report The Color of Crime notes, gambling offenses are the only category of crime for which Asians are more likely than whites to be arrested.

| LETTERS FROM READERS |

|---|

Sir — The June article by Alex Kurtagić on “Black Metal” music contained two very serious omissions. Varg Vikernes, one of the originators of National Socialist Black Metal (NSBM) music did not receive a long prison sentence for “church arson.” He received a sentence of 21 years for murdering a business partner. He was also found guilty of church arson, and not of just any church. Mr. Vikernes burned a 12th-century stave church, a national treasure, clear to the ground. He was also responsible for less severe arson damage to several other historic stave churches. No one who cares about preserving history or culture can look upon the destruction of a major historical site with anything but revulsion. Mr. Vikernes was paroled in 2009, after fewer than 16 years. He could have gotten out even earlier if he had not made an escape attempt.

The German Hendrik Möbus is another dastardly character. Mr. Kurtagić admiringly says that Mr. Möbus was persecuted and even imprisoned by the German authorities for loyalty to his beliefs. In fact, he was imprisoned for murder. When Mr. Möbus was a teenager, he and some accomplices strangled a 15-year-old classmate with an electric cord. These thugs were paroled after fewer than five years behind bars.

Mr. Möbus then immediately got in trouble by publicly mocking his victim and giving a “Hitler salute” in a public place. He fled to the United States, where he briefly flirted with the extreme underground music scene here before being deported to Germany and again imprisoned for parole violations. People involved in the “scene” tell me that while he was in the United States he committed serious crimes in two different states. He was beaten in a vigilante reprisal after the first incident, but the victims never filed criminal charges.

The liberal German judicial system seems more interested in Mr. Möbus for “speech crimes” than murder, but that is no reason to pretend he is not a villain. I think both Mr. Vikernes and Mr. Möbus should have been executed for their crimes.

I also disagree with Mr. Kurtagić’s assessment of “black metal.” What he calls “NSBM” does not have any significant following and is mostly “garage bands” with tiny press runs on home-based “labels.” The lyrics are all about shock value, not meaningful politics. The only band referred to as “NSBM” that you might actually find in a record store is the Polish band Graveland. While Graveland is explicitly “pro-white,” the front man for the band says he does not use the term “NSBM.” He says his goal is not politics, but to “fight the Catholic church in Poland.” The music is more about crude shock value than anything else.

Kyle Rogers, South Carolina

Sir — As a long-time metal fan I enjoyed reading your June article about nationalist music and political dissent. If you watch musicians on television with the sound turned off, you could say that metal music does what other genres only pretend to do. Music is fantasy, and the elaborate staging of some heavy metal groups is the most fantastic.

I have watched, however, as metal music went from being a major music preference, selling out sports arenas around the country, to relative obscurity as it became more right wing, around the peak of its popularity in the 1980s. Also, it may be difficult for a novice to enjoy some of the more extreme-sounding bands. Bands like Slayer began to use too much dissonance, the so-called “devils chord.” Their music is deliberately grating, perhaps in an attempt to bring to life the disharmony youngsters feel during adolescence. In the famous “mockumentary” This is Spinal Tap, the director notes that musicians don’t seem to want to grow up. Metal seemed to have its last mainstream hurrah with the sleaze band Guns and Roses, a band some say was a fusion of heavy metal pop and the harder bands of the period.

Name withheld

Sir — I want to complement AR on publishing Alex Kurtagić’s article. Even though I am a traditional Catholic (member of the Society of St. Pius X) and found the cover illustration somewhat disturbing, I found the article most interesting and insightful. The Catholic Church has been the number-one patron of the arts through the centuries. And even profane art — if well done — can be an interesting expression of our human condition that seeks to know God.

Name withheld

Sir — I read with interest the article about the average IQ of Italians in your May issue. It said that Richard Lynn has found that northern Italians are as smart as any European, but southerners have lower IQs because of admixture with North Africans. This appears to me to contradict Prof. Lynn’s earlier findings in his 2002 book, IQ and the Wealth of Nations, which he coauthored with Tatu Vanhanen. At that time, he reported the IQ of Italians as 102, which tied them with the Germans, Dutch, and Austrians for the highest in Europe (Sweden and Switzerland were 101, France was 98). Did Prof. Lynn just discover the North African admixture?

Gregory F. Peischl, Austria

You must enable Javascript in your browser.