August 2001

| American Renaissance magazine | |

|---|---|

| Vol. 12, No. 8 | August 2001 |

| CONTENTS |

|---|

Writing on the Wall

Race and Politics

How They Got the Vote

O Tempora, O Mores!

Letters from Readers

| COVER STORY |

|---|

Writing on the Wall

The 2000 Census is warning us

The 2000 Census counted 281.4 million Americans, a 13.1 percent increase over the 1990 total of 248.7 million. In 1990, non-Hispanic whites were more than 75 percent of the total population, but in just ten years had slipped to 69.1 percent. Blacks, at 12.3 percent were, for the first time, outnumbered by Hispanics at 12.5 percent. Asians (3.5 percent) and a mix of American Indians, native Hawaiians and other non-whites (2.5 percent) accounted for the rest.

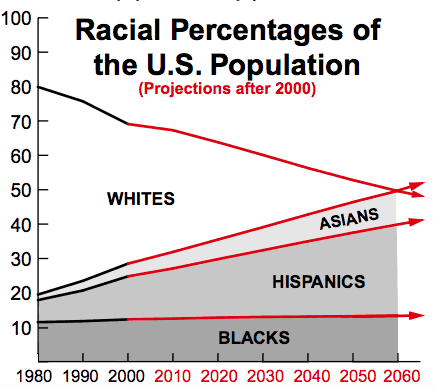

This graph shows how the white percentage of the population has changed as the proportion of non-whites has increased. According to the Census Bureau, if current trends in immigration and birthrates continue, whites will drop to just under 50 percent of the population in 2060.

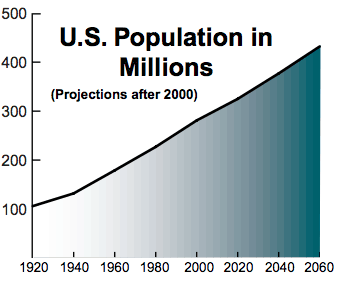

Blacks are projected to increase slightly to 13.3 percent, while Hispanics would account for 26.6 percent and Asians for 9.8 percent. At that point, the total U.S. population is projected to be more than 432 million, which would mean another 145 million people — the equivalent of absorbing the total population of the United States in 1945.

In fact, if current trends continue, whites will become a minority sometime before 2060. This is because the projections represented in the graph do not take 2000 census data into account. Before the count, Census Bureau demographers expected to find, at most, 275.8 million people, and the racial projections were based on that expectation. The actual count of 281.4 million was 5.6 million more than the highest estimate, which means we had the equivalent of two more Chicagos the bureau had not expected to find. These 5.6 million people and their descendants — overwhelmingly non-white — will hasten the day when whites become a minority.

Silent Invasion

The difference between the expected and actual counts is due mainly to illegal immigration. For the 2000 census, the bureau tried very hard to count illegals, and appears to have succeeded beyond its expectations. However, since most of them don’t want anything to do with the government, many escaped the count anyway, and no one really knows how many there are. In 1993, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) thought there were some three million, and the official 2000 figure for illegals doubles that to at least six million. Researchers at Northeastern University in Boston estimate the number at closer to 13 million, and believe it increases by 500,000 to one million every year.

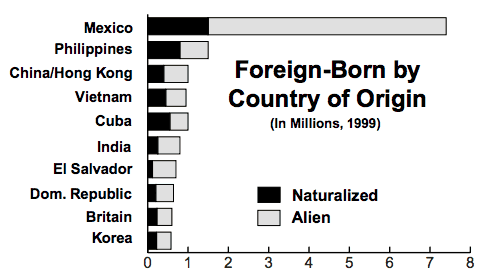

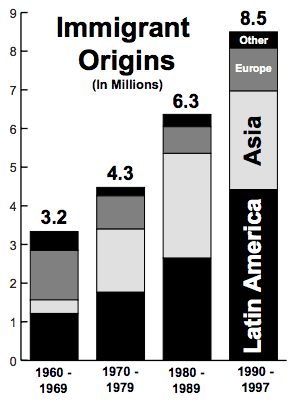

The legal immigrant population is also growing at 700,000 to 900,000 per year. The foreign-born population of the United States now exceeds 27 million, and one out of every 10 Americans is foreign-born, a figure not reached since the 1930s. (One quarter of the federal prison population is foreign born, which means foreigners are 2.5 times more likely than natives to end up in a federal jail.) This graph shows which countries send the most people and how many naturalize. Current levels of immigration are much higher than the historical average, and have doubled in 20 years. The subsequent graph depicts this sharp increase (illegal immigration is not included), and the regions of the world from which immigrants come. In this graph, the decade of the 1990s still has two more years to run but has already racked up an unprecedented 8.5 million legal immigrants.

Because of changes in the law since the Immigration Act of 1965, approximately 90 percent of legal immigrants are non-white. Practically all illegal immigrants are non-white, which explains why 98 percent of the 2,684,892 illegals granted amnesty by the 1986 Immigration and Control Act were from the Third World: Africa, Asia, Latin America or the Caribbean. The number of immigrants increases every decade, and very few are white.

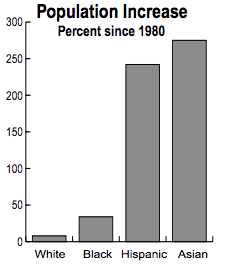

The 32.7 million rise in the population since 1990 is the single largest one-decade increase in the nation’s history. The Hispanic population grew by 57.9 percent, Asians by 48.3 percent, blacks by 16.2 percent, and whites by just 5.9 percent. The census bureau considers Middle Easterners and North Africans — Iranians, Iraqis, Syrians, Egyptians — to be white. More than 1 million have immigrated since 1970, and have produced an estimated 1 million children. These 2 million should be subtracted from the growth of the “white” population.

Of the country’s 35 million Hispanics, more than 20 million, or nearly 60 percent, are Mexicans. In 1960, there were fewer than two million Mexicans in the United States. So many Mexicans have moved north in recent years that some of the poorer parts of Mexico are effectively depopulated.

By 2060, the census bureau projects a Hispanic population of 114.8 million — more than one quarter of the total projected population, and greater than the entire population of the United States in 1920. As we have noted, this figure is based on projections that are already outdated.

The expanding Hispanic population has already helped reduce whites to a minority in California (now 46.7 percent white, 6.7 percent black, 10.9 percent Asian, 32.4 percent Hispanic), New Mexico (44.7 percent white, 1.9 percent black, 1.1 percent Asian, 42.1 percent Hispanic), Hawaii (22.9 percent white, 1.8 percent black, 41.6 percent Asian, 7.2 percent Hispanic), and the District of Columbia (27.8 percent white, 60 percent black, 2.7 percent Asian, and 7.9 percent Hispanic). In Texas (52.5 percent white, 11.5 percent black, 2.6 percent Asian, 32 percent Hispanic), whites are forecast to become a minority in 2004.

Fertility

Immigration is now the determining factor in US population growth. Since 1970, nearly 30 million immigrants — roughly one-third of all the people who ever came to America — have settled in the United States. Immigration and births to immigrants have accounted for 70 percent of the increase in US population since then, and the immigrant population is growing six-and-a-half times faster than the native-born population. Without this influx, the current population would be just over 226 million, or approximately what it was in 1980.

“Replacement-level fertility” is the number of children the average woman must have during her lifetime just to replace herself and her spouse. This figure is set at 2.11 rather than 2.0 to include a margin for premature deaths. If there is no emigration or immigration, a population with average lifetime fertility of 2.11 will eventually level off. It can continue to grow, even with replacement-level fertility, if people are disproportionately young. In 1972, the total fertility rate of American women dipped below replacement level for the first time, and the white rate is now well below replacement level. This means long-term population growth is fueled exclusively by immigration.

In 1997, there were approximately 3.9 million births in the United States, reflecting a total fertility rate of 2.04. Non-whites, who are younger than whites and have higher fertility rates, were 28 percent of the population but accounted for 40 percent of the births. Hispanics have the highest lifetime fertility of any group, but are still below the figure of 3.326, reached in 1960-1964 as the the baby boom was ending. Because of their high fertility, Hispanic women have given birth to more children than black women every year since 1993.

Low white fertility means white children are an even smaller percentage of the population than whites as a whole, and are projected to shift to minority status at least 20 years sooner. Although 69.1 percent of the total population is white, only 60.9 percent of children under 18 are white, and are expected to become a minority in 2037. These projections do not include the unexpectedly large number of non-whites found in the 2000 census, so the transition is likely to take place even sooner.

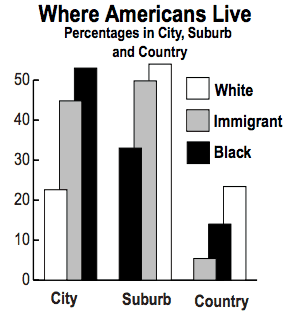

Whites are moving away from areas hardest hit by immigration, especially the big cities. They are now a majority in only 52 of the 100 largest cities, down from 70 in 1990. More than two million whites left these cities since 1990, as more than 3.8 million Hispanics moved in. Over half of all whites live in suburbs, but more and more are fleeing to the country, which is still overwhelmingly white. Only 22.6 percent of whites now live in central cities (44.8 percent of immigrants live in cities). That figure is now smaller than the 23.4 percent of whites who live in rural areas (only 5.4 percent of immigrants live in the country). Blacks have residency patterns more like immigrants, with 53 percent in the cities, 33 percent in suburbs, and only 14 percent in the country.

Insanity

Our immigration policy is, in a word, insane. Even if every newcomer were white, well-educated, and English-speaking, it would be folly to expect the country to absorb another 150 million people over the next 60 years. The first two graphs end at 2060, but the Census Bureau happily forecasts yet more millions in the decades to come. We decry our dependence on foreign raw materials, and cannot generate enough electricity for the millions who have swarmed into California, yet we are supposed to be looking forward to yet more sprawl, congestion, crowding, and pollution.

And, of course, the vast majority of immigrants are not white, well-educated, English-speakers. We never tire of telling ourselves how important education is, yet we import millions of people who are illiterate in their own languages. We claim to want to improve the health of Americans, yet we import people sick with diseases like tuberculosis, which we once eradicated, and leprosy, which is exclusively an immigrant disease. We have spent billions trying to fight poverty, yet we let in millions who own nothing more than the clothes they wear. It would be hard to think of a government policy more flagrantly in opposition to the expressed goals of our society than immigration.

Americans have repeatedly told pollsters they want less immigration, and whites (and blacks) continue to move away from those parts of the country that immigration has transformed — and with good reason. Crime, ethnic conflict, deteriorating schools, and contempt for European civilization have been the invariable result of massive influxes of Third Worlders. In the long term, there is no guarantee that an increasingly non-white America will continue to abide by the institutions white nations — and virtually only white nations — take for granted: the rule of law, freedom of speech, constitutional government. Our children and grand-children will live to see the results of this reckless experiment with the basic identity of a once-great nation.

One of the most important roles of government is to avert catastrophes, both near and distant. This is why we have an army, public health, police, and an environmental policy. The current flood of Third-World immigration is a completely unnecessary catastrophe brought on by the very government that is supposed to be working for our interests. It is not just insane; it is criminal.

Stephen Webster is assistant editor of American Renaissance.

| ARTICLE |

|---|

Race and Politics

What it’s like in Los Angeles

Race, we are told, is a meaningless social construct. California, we are told, points the way to America’s happy, diverse future. But if the June mayoral race in Los Angeles is any indication, diversity only breathes new life into meaningless social constructs that seem to get more meaningful all the time. The contest was an odd one — a Hispanic backed by the city’s white/Jewish political machine ran against a white gentile backed by nearly 100 percent of the city’s blacks — but it had race, and the reality of race, written all over it.

Los Angeles (Credit Image: © Image Source / Image Source / ZUMAPRESS.com)

The contest might not have been so racially charged if it had not come just after the March release of the 2000 census results. Hispanics gloried in reports that they were now 46.5 percent of the city, up from 39.3 percent in 1990. Whites were down to 29.8 percent from 37.5, and blacks dropped from 13.9 to 11.2. Asians held steady at just under 10 percent.

Blacks have felt the surge in Hispanics much more acutely than whites because they compete for the same low-skilled jobs. They also compete for low-rent apartments, which are increasingly filling up with Mexicans. Many blacks, who cannot afford to live on Los Angeles’ upscale West Side, have no choice but to leave, and since 1990, the city has lost more than 70,000 blacks. Some are moving to suburbs but many are part of a California exodus that is taking them back to the south. These days, even the city of Compton, the birthplace of “gangsta rap,” which used to be virtually all black, is 39 percent Hispanic.

Blacks and Hispanics do not get along. Blacks see Hispanics — whom they often call “beans” or “beaners” — as usurpers from another country, who cross the border to enjoy benefits blacks think only they deserve. Blacks consider manual labor beneath them, and mock Hispanics for doing it. In the ghettos, everyone wants to be a “player,” draped in gold and sporting a pager. Blacks tend to think of all Mexicans as stoop laborers and fruit pickers.

Hispanics counter that they went through great hardship to get to America, and have earned citizenship by working long hours at back-breaking jobs. They look down on black women for living on welfare and black men for abandoning their children.

Both groups think of themselves as superior to the other, and there is surprisingly little intermarriage. For each group, it is a social step down to mix with the other, while it is a step up to mix with whites. Traditionally, blacks have defined success as making it into the white world, and have spent years trying to secure access to white jobs, white schools, and white neighborhoods. They see no future in a Hispanic city.

When blacks and Hispanics make contact there is friction. Street gang killings have left many casualties on both sides, and school violence has been widespread. The 1970s busing craze drove most whites out of the L.A. schools, and throughout the 1980s, there were frequent black/Hispanic brawls, gang fights, and acts of individual violence. The warfare declined in the 1990s only as blacks fled the district, leaving it mostly Hispanic.

The changing demographics threaten what little hold blacks still have on Los Angeles politics. They have had a steady presence on the City Council, the Board of Supervisors, and the school board, but their political base is eroding as blacks move out and Hispanics move in. Voting patterns always seem to reflect meaningless social constructs.

Another striking difference between blacks and Hispanics is political style. Blacks specialize in loud, often violent political activism uncommon among Hispanics. In black areas the most revered figure is often the local Al Sharpton-type, who seems to hold no job other than professional protester. Any given block in a black neighborhood has an abundance of “community leaders,” able to whip up a demonstration in no time.

This is not true for Hispanics, especially Mexicans. Their neighborhoods are not full of “community leaders,” and most would be hard-pressed to name a single Mexican-American political icon other than Cesar Chavez. Vote-pandering whites who wanted to rename Los Angeles streets in honor of Mexican political heroes quickly ran out of candidates.

Hispanic writers and intellectuals have tried very hard to drum up protest-power, and the Los Angeles Times has given them the perfect platform. Its “Latino outreach program” has packed the paper with Hispanic columnists, reporters and editors, and now about half the by-lines in the Metro Section are Hispanic. The test case for Hispanic mobilization came last year, when a newly-elected school board prepared to remove Ruben Zacarias, the city’s first Hispanic school superintendent. Frank Del Olmo, a typical Times Hispanic, wrote there would be “holy war” if Mr. Zacarias got the boot, and threatened retaliation, warning that “Mexicans have long memories.” The only trouble was, ordinary Hispanics didn’t care. Sit-ins and protests at the school board flopped, drawing only a few dozen people.

In an ironic twist, black journalists attacked Hispanics for “divisive, racist” politics. Earl Ofari Hutchinson, an L.A. institution and specialist in “black rage,” scolded Hispanics for injecting race into the important business of removing an incompetent. This black/Hispanic fight over who should run an overwhelmingly-Hispanic school district set the stage nicely for the mayor’s race.

Heartened by the new census data, Hispanics decided 2001 would be their year for a breakthrough. At 41 percent, registered Hispanic voters easily outnumbered the 34 percent that were white. The race would be a cakewalk.

The open primary included Antonio Villaraigosa, a Democrat and former speaker of the California State Assembly, and L.A. City Attorney James Hahn, also a Democrat. There was one no-hope Republican and a few other Democrats, but attention focused quickly on Mr. Villaraigosa and Mr. Hahn.

Despite his obvious appeal to the “social construct” vote, Mr. Villaraigosa had unpleasant baggage. He lobbied President Clinton to pardon cocaine-runner Carlos Vignall, arguing that a “racist” justice system had “railroaded” him. When first asked about this, he lied, owning up only when the proof was overwhelming. He had a string of illegitimate children, and spent ten years in a criminal gang (he had the gang tattoos surgically removed years ago). He had a 1.4 grade point average when he was expelled from high school, and was an Aztlan booster in college. Needless to say, he presented himself as a great success story who had turned his life around against daunting odds. The National Organization for Women endorsed him because he took his wife’s name when he finally married.

James Hahn, his most serious opponent, is the son of legendary city supervisor Kenneth Hahn, a political hero to liberals and blacks. Known as “Daddy” Hahn, he was famous for staying in South L.A. after it turned black in the 1960s. He was a leader in the “civil rights” movement and did plenty of favors for blacks. He sent young Jimmy to public school, where he admits he was taunted and beaten up for being white. He now says this “sensitized” him to the plight of minorities. James went into politics in his father’s footsteps, and was City Controller under black mayor Tom Bradley. From the beginning he took a strong position in favor of law and order — the only political stance that distinguished him from his opponent.

Mr. Villaraigosa won the primary, with Mr. Hahn the only other candidate to do well enough to make it into a runoff. The lines were now drawn, with Hispanics convinced their day of glory had come. Gregory Rodriguez gloated in the Times that a Villaraigosa victory was a “historic inevitability,” and that this would usher in “a new political era” of “ethnic ascendance.” R. Venable de Rodriguez (no relation), also in the Times, wrote that California would be swallowed up by Mexico: “The idea of an active reconquest of Mexican territory is in the air. But the reality of cultural re-absorption already renders it a foregone conclusion.”

More endorsements piled up, as organizations looked at the census data. Although both candidates were Democrats, the party endorsed only Mr. Villaraigosa, as did Senator Barbara Boxer, Governor Gray Davis, the Sierra Club, outgoing mayor Richard Riordan, and practically every Hispanic office holder in southern California. In its own endorsement, the Times coyly referred to their candidate’s old gangs as “clubs.”

Even L.A.’s Jewish kingmakers Eli Broad and Robert Burkle, who had been Mayor Richard Riordan’s main backers, endorsed Mr. Villaraigosa. The city’s Jewish community had made the difference 30 years ago when Tom Bradley was elected mayor. Back then, blacks were the “wave of the future,” and now the money elite sensed another change. (The Republican Mr. Riordan disagrees with just about everything Mr. Villaraigosa stands for. His endorsement made more sense after he announced he might run for governor — a campaign that would certainly require the support of Messrs. Broad and Burkle.)

Mr. Villaraigosa even got the endorsement of one prominent black, though this was a story about money rather than rainbow coalitions. Genethia Hayes was elected president of the L.A. School Board in 1999 on a campaign to fight bilingual education and other liberal reforms — and with money from Mr. Riordan’s Jewish backers. One might have expected a black school board president to oppose a Hispanic who sends his children to private school because he would not “risk” sending them to her schools, but Miss Hayes appears to have let the money do the talking.

The message was clear: The L.A. political machine saw a brown future, and wanted to back the winning team. The party and its war chest lined up behind Mr. Villaraigosa, who was now outspending Mr. Hahn nearly five-to-one. As young blacks in the street put it, “the machine wants a bean.”

If whites have had racial consciousness beaten out of them, blacks have not, and the fawning over Mr. Villaraigosa was like a red rag to a bull. Blacks lined up behind Mr. Hahn in a way that dwarfed their support for any black candidate for the past 20 years. Nearly every local black politician and personality, from Congresswoman Maxine Waters to Magic Johnson to the widow of Tom Bradley stumped for Mr. Hahn. Every soul-food restaurant was festooned with Hahn placards. Black support for Mr. Hahn was not new, but its urgency showed how important this election was. For many blacks, this seemed like the last chance to have a political presence in city hall, if only by proxy.

This was not the first political fight between blacks and Hispanics. Blacks overwhelmingly supported Proposition 187, the 1994 initiative to prevent illegals from getting government benefits, as well as the more recent initiative to do away with bilingual education, but never had racial division been so clear.

Naturally, Hispanics at the Times blasted blacks for “racial divisiveness.” Columnist Steve Lopez wrote that blacks “prefer a dead white man to a living Mexican” (a reference to Mr. Hahn’s late father). Not one Times columnist or contributor endorsed Mr. Hahn.

He did win the support of one racial group with few votes but plenty of money: California Indians. Mr. Villaraigosa fervently believes illegal immigrants have the right to live off taxpayer largesse but condemns tribes that want to support themselves by building casinos. Angry tribal leaders funneled more than $100,000 into the Hahn campaign.

For Mr. Villaraigosa’s supporters, though, there was so little to worry about they spent the first few weeks after the primary planning victory parties. The math was simple: Mr. Hahn could win 100 percent of the black vote and even every conservative-to-moderate white; there were still enough Hispanics to put their man over the top. It didn’t seem to matter that the Times’ claque of hired Hispanics were not very enthusiastic about him. Steve Lopez complained he was not radical enough. Gregory Rodriguez said he was not centrist enough. Frank Del Olmo said he was a weak candidate. Yet all these men supported Mr. Villaraigosa and urged all Hispanics to do the same. It was Ruben Zacarias all over again; race trumps ability.

Mr. Villaraigosa carefully wove ethnicity into his campaign. His slogan was Si Se Puede (“Yes We Can”), and there was Mariachi music before every stump speech. Mr. Hahn never mentioned race, but he hit hard at the Vignall pardon and Mr. Villaraigosa’s record on crime (in the assembly he opposed harsher penalties for child molesters and kiddie-pornographers). He also turned Mr. Villaraigosa’s huge war chest and endless endorsements against him, portraying himself as David against Goliath.

A week before the election, polls showed Mr. Hahn with as much as a 10 percent lead. More than a quarter of Hispanic voters were saying they would vote for Mr. Hahn, usually citing his tough stand on crime. The Villaraigosa camp panicked, and tried desperately to woo non-Hispanics. The candidate spent hours at Jewish delis and festivals, and said that although he was raised a Catholic he prefers Judaism. He also ginned up a new set of campaign flyers. One was for retired whites (“Villaraigosa will keep seniors safe”), and another, featuring a cuddly dog and cat, targeted animal-rights activists (“Villaraigosa: the animal-friendly candidate”). He even imported a black supporter from Harvard, Cornel West, who stayed by his side for the last week. Most blacks I talked to thought Prof. West was a pathetic sell-out.

Mr. Villaraigosa’s attempt to woo blacks was not helped by events in the last days of the campaign. Some time before, a Hispanic had kidnapped, tortured and shot a black named Anthony Lewis because he mistakenly thought Mr. Lewis was dating a Hispanic. The gunman fled in a stolen bus and his flight, captured live on television, ended only when he crashed into a SUV, killing the Hispanic driver. Mr. Lewis, who survived the shooting, got out of hospital just a few days before the election. His media interviews, which were the top story on most newscasts, hardly improved black/Hispanic relations. About the same time, locals at a Mexican bar murdered a black tourist.

This was all perfect timing for Mr. Hahn, who spent the last Sunday before the election at an all-black church, speaking to roaring crowds while the choir sang “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough.” Mr. Villaraigosa spent the day at the Valley Jewish Fair. He told the media to ignore the polls; he had a silent army of 5,000 Hispanic activists who would shuttle supporters to voting stations.

He shouldn’t have been so smug. He lost the election, 46 percent to 53 percent, a margin of 40,000 votes. Mr. Villaraigosa got almost exactly 80 percent of the Hispanic vote, but most Hispanics stayed home. Of 600,000 eligibles only 130,000 turned out. So much for “ethnic ascendancy” — at least for now. Mr. Hahn got essentially all the black vote, 65 percent of the Asian vote, and about 60 percent of the white vote. The Jewish vote split about 50:50 with older, more conservative Jews voting for Mr. Hahn, and younger liberals for Mr. Villaraigosa. It was white turnout that tipped the balance for Mr. Hahn. Whites were only 34 percent of the registered voters but cast 52 percent of the votes. If only ten percent more Hispanics had bothered to vote, Mr. Villaraigosa would have won.

There was predictable outrage from Hispanic activists — but not at their brethren for staying home. Mr. Hahn won through “prejudice and bigotry,” wrote David Ayon in the Times, although the only example he could give was that Mr. Hahn dared to ask Mr. Villaraigosa “why he didn’t support tough laws against gang violence.” Frank Del Olmo, who had threatened reprisals when Ruben Zacarias was fired, bemoaned Mr. Villaraigosa’s “failure to make history,” but suggested he should run the school system. “The L.A. Unified School District is already a disaster area,” he wrote, “so Villaraigosa couldn’t be blamed for making it any worse.” Mr. Del Olmo doesn’t appear to care about qualifications; only about making sure Hispanics get the top jobs.

The long-term expectations of the Villaraigosa camp were perhaps best expressed in an op-ed piece in The New York Times by Harold Meyerson, executive editor of L.A. Weekly, the city’s largest-circulation free weekly that makes the L.A. Times look conservative. “For now, the future is on hold,” he wrote. Mr. Hahn had managed to “defer what looked to be L.A.’s destiny,” and win “one last victory for the old Los Angeles.”

It may be tempting to agree that this is the “last victory” before Hispanics take over. However, Californians have voted to end affirmative action, bilingual education, and handouts to illegals, despite constant pummeling by multiculturalists. This time, in ultra-liberal L.A., voters were told that absorption by Mexico was an inevitability and that they should vote in a Hispanic. They didn’t buy it. Another lesson is that as a practical matter, blacks may make good allies in the fight to stop immigration. If we have blacks allies it makes it harder for Hispanic activists to call us “white supremacists.” Finally, the combination of high white and low Hispanic voter turnout suggests that, for the time being, demography is not destiny. It is still possible, through the ballot box, to help determine the future of our country.

Desmond Boles is the pen name of a Los Angeles resident who works in the film industry.

| ARTICLE |

|---|

How They Got the Vote

Granting the franchise to blacks, women, paupers, and teen-agers

Alexander Keyssar, The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States, Basic Books, 2000, $30.00, 467 pp.

Except for occasional backtracking, the history of the franchise in the United States has been one of constant expansion. In colonial times and in most areas after the Revolution, only white property-owners, age 21 or over could vote. Every one of those restrictions has since been abolished, and now any non-felon age 18 or over can vote. Why? What prompted people who had the vote to give it to those who did not? Alexander Keyssar, who is a professor of history and public policy at Duke University, tells us this is the first book ever written about that process. Needless to say, Prof. Keyssar is delighted things turned out as they did and thinks they should go further still. However, in this well-researched account he manages most of the time to keep a leash on his liberal impulses and even occasionally to outline some of the arguments made to oppose expanding the franchise.

Property

Part of the colonial legacy was a conviction that only men of property had enough independence of mind and a sufficient stake in society to be trusted with the vote. Servants, women, and the poor were too dependent on the authority of others. There was also a broad conviction that opportunities were so great in the colonies that only the shiftless failed to acquire property. In the late colonial period perhaps just under 60 percent of white men owned property and could vote.

The Revolution required every state to establish a new government and to reopen the question of whether the vote was a right or a privilege. Given the radical sentiment of the times, it is surprising that only one state — Vermont — abolished the property qualification. The drafters of the federal Constitution wanted to let only landholders vote in federal elections, but did not write in a property requirement for fear it might prevent ratification. The federal government left the determination of voter qualifications entirely to the states.

There were contradictions in arguments both for and against giving the vote to the propertyless. To say voting was a natural right regardless of wealth opened the door to giving it to women and blacks, which almost no one wanted to do. As John Adams put it in 1776:

“Depend upon it, Sir, it is dangerous to open so fruitful a source of controversy and altercation as would be opened by attempting to alter the qualifications of voters; there will be no end of it. New claims will arise; women will demand the vote; lads from twelve to twenty-one will think their rights not enough attended to; and every man who has not a farthing, will demand an equal voice with any other in all acts of state. It tends to confound and destroy all distinctions, and prostrate all ranks to one common level.”

Supporters of the property requirement also contradicted themselves. They said the propertyless would vote like sheep, as instructed by their employers, but also that they would vote selfishly against the established interests of their betters.

The process of seceding from England loosened voter qualifications in some states but tightened them in others. Before independence, Catholics could not vote in five states, and Jews were disfranchised in four; after independence they could vote everywhere. Massachusetts, however, had a stricter property requirement after the Revolution than before. The initial republican impetus did not have the universally leveling effect one might have expected.

However, as Prof. Keyssar points out, war itself tends to broaden the franchise, and this was true of both the Revolution and the War of 1812. Propertyless soldiers circulated petitions demanding the vote, and the upper classes wondered whether disfranchised men would shoulder arms with sufficient enthusiasm. Ben Franklin was among those who argued that a propertyless man with the vote was a better ally than one without it.

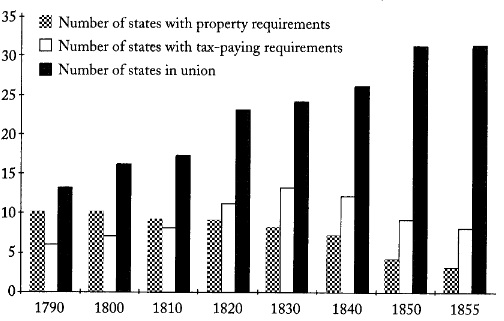

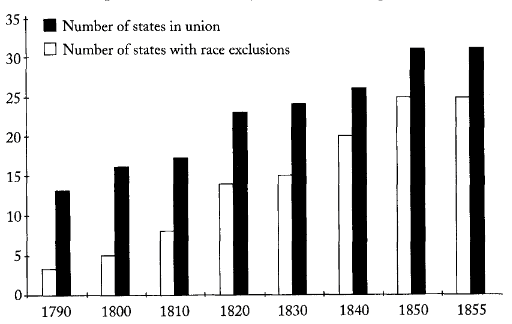

Many states relaxed or abolished property requirements during this period, and none of the new states admitted after 1790 had the requirement in its original constitution (see graph above). Prof. Keyssar notes that in the early years, many people were particularly loathe to give the vote to landless urban workers. Not a few states dropped the property requirement on the mistaken assumption that in so vast a country as the United States, most men would always be farmers, and that there would never be an urban proletariat.

Virginia was the last state to have a property requirement for all electors, abolishing it only in the mid 1850s. By this time the only such qualifications targeted specific groups: New York had a property requirement only for blacks and Rhode Island had one only for the foreign-born.

After the Civil War, when it became clear industrialization had produced the very urban proletariat agrarians had feared, there was a revival of sentiment against letting all men vote. Prof. Keyssar quotes Chancellor Kent of New York, who decried “the tendency in the poor to covet and to share the plunder of the rich; in the debtor to relax or avoid the obligation of contracts; in the majority to tyrannize over the minority, and trample down their rights; in the indolent and the profligate to cast the whole burthen of society upon the industrious and the virtuous.” Kent concluded that “the poor man’s interest is always in opposition to his duty,” and lamented that there was no way by which to take back the vote from the propertyless.

The arrival of large numbers of immigrants in the 1870s and 1880s also dampened enthusiasm for manhood suffrage. In words no less relevant today, America’s most celebrated historian, Francis Parkman, complained in 1878 about “restless workmen, foreigners for the most part, to whom liberty means license and politics means plunder, to whom the public good is nothing and their own most trivial interests everything, who love the country for what they can get out of it . . .” In his view, the masses “want equality more than they want liberty.”

A variant of the property requirement is exclusion of paupers from the vote. Americans have traditionally thought anyone on public relief forfeits his say in government, but the Great Depression cast doubt on this principle. Suddenly there were so many responsible, hard-working men on relief it was difficult to deny them the vote. The Supreme Court finally did away with all pauper exclusions in 1966, at the same time it abolished the poll tax. These activist decisions, which were part of a concerted move to federalize all voting laws, struck down the final vestiges of what had, for centuries, been a central qualification for the franchise: property.

Blacks

At various times during the colonial or early post-revolutionary period, free blacks could vote in North Carolina, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Vermont. After independence three states quickly took back the franchise from blacks — New Jersey, Maryland, and Connecticut — and New York effectively cut off all but a handful of black voters by passing a property requirement for blacks only. Every state that entered the union after 1819 denied blacks the franchise, and in 1855 they could vote only in Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, and Rhode Island (see graph below) Together, these states held only four percent of the nation’s blacks. The federal government prohibited free Negroes from voting in the territories it controlled, and in 1857 the Supreme Court ruled that blacks, free or slave, could not be citizens of the United States, though they might be citizens of a state.

When new states joined the union, it was common at least to discuss the possibility of letting blacks vote, and from time to time referenda and constitutional conventions considered the question. The proposals always lost, usually by wide margins. At the Indiana convention of 1850, one delegate even offered an amendment “that all persons voting for negro suffrage shall themselves be disfranchised.” Many people in the north argued that giving blacks the vote would attract freedmen and runaways, and most whites wanted nothing to do with blacks.

The Civil War appears to have changed the thinking of some northerners about race, if only because war passions made it easier to oppose the practices of the enemy. The 13th amendment, ratified in 1865, emancipated the slaves, and the 14th amendment set out penalties for states that disfranchised voters on the basis of race. Representation in Congress and the electoral college was to be reduced by the proportion of the electorate denied the vote because of race. This was obviously directed at the south; northern and western states with few blacks could disfranchise them at little cost. The amendment is significant in that although it penalized racial discrimination, it accepted it in principle.

The ratification history of the 15th amendment — which in 1870 forbade withholding the vote on racial grounds — is instructive. It passed easily only in New England, where there were few blacks. It was ratified in southern legislatures, but by the same fraudulent procedure used to ratify the other Civil War amendments. Reconstruction governments were unrepresentative of the white majority, and for four former Confederate states, ratification was a condition for readmission to the Union.

In the Western part of the country, there was much opposition to the amendment for fear it would give the vote to the Chinese. Although Rhode Island had already let blacks vote, it barred the Irish from the polls. Ratification was long delayed, and nearly failed for fear the amendment would give the Irish “race” the vote. Prof. Keyssar points out that the amendment did not reflect a desire for racial equality so much as political calculation and zeal for punishing the south. Republicans were certain most blacks would vote for their party, and wanted to expand their constituency in the south, while in the north there were not enough black voters to cause trouble.

With Redemption, or the overthrow of Reconstruction governments, southern whites found many ways to minimize the black vote. One was simply to throw out returns from black areas. When, in 1884, Grover Cleveland became the first Democratic president since the Civil War, Republicans complained that the narrow margin of victory would have been reversed if the heavily-Republican southern black vote had not been ignored.

Soon southern states had regulations that did not explicitly disfranchise blacks but had the same effect: literacy tests, residency requirements, poll taxes, and complex registration schemes. In some states, white men were “grandfathered,” or exempted from these requirements if they had served in the Confederate army or if their ancestors had voted in the 1860s. Elsewhere, middle-class whites were happy to disfranchise “ignorant, incompetent and vicious” white men along with blacks.

Whites made no secret of their intentions. As Carter Glass explained at Virginia’s constitutional convention of 1901-02: “Discrimination! Why, that is precisely what we propose. That, exactly, is what this Convention was elected for — to discriminate to the very extremity of permissible action under the limitations of the Federal Constitution, with a view to the elimination of every negro voter who can be gotten rid of . . .”

Many were gotten rid of. In 1896 there were still 130,000 registered black voters in Louisiana; by 1904, new restrictions had reduced that number to only 1,342. After Mississippi passed new voting laws in 1890, there were only 9,000 registered blacks out of an eligible population of 147,000.

Even when blacks managed to register, the white Democratic primary meant their votes meant nothing. In many southern states, the Republican party — the party of Lincoln — had no white following at all. The real contest took place in the Democratic primary, with the general election a mere formality. Many state Democratic parties declared themselves private clubs open only to whites. This way the primary vote, which was all that mattered, completely excluded blacks.

The north quickly lost interest in policing southern whites, and there were only sporadic calls to exercise the 14th amendment’s provisions to limit representation in Congress and the electoral college. The Supreme Court went on to uphold every major disfranchisement technique.

But it was, of course, the Supreme Court that eventually dismantled these techniques. Although it had ruled in 1935 that white primaries were Constitutional, a Supreme Court composed almost exclusively of Roosevelt New Dealers reversed course in 1944. This was the beginning of a complete federal takeover of state election laws that included the Voting Rights Act of 1965, its expansion to include “language minorities,” and the more recent struggle over “majority-minority” districts. For Prof. Keyssar, the federal triumph is best symbolized by the fact that in 1960 many Puerto Ricans were kept from the polls by English-language literacy tests, but by 1976 they got ballots in Spanish.

Why, after some 80 years of paying no attention to blacks, did Congress and the Supreme Court suddenly insist on ensuring their voting rights? Prof. Keyssar suggests that in the competition with Soviet Communism for world leadership, racial discrimination was the Achilles heel of American democracy. There may be something to this, but anti-racism was just one part of a liberal/socialist revolution that left nothing unchanged. Competition with Communism hardly required the sexual revolution, the decline of good manners, women’s “liberation,” hippies, or the relentless expansion of federal power. Anti-racism was one more frantic act of a culture devouring itself, not a way to prove we were as good as the Soviets.

Prof. Keyssar is more interesting when he notes the ways in which whites distinguished between blacks and Indians. Even in the earliest days, Indians were only rarely barred from the polls on racial grounds; they were admitted if they were civilized and paid taxes. The 14th amendment granted Indians citizenship and the right to vote in federal elections, but an 1884 Supreme Court decision ruled that the amendment’s grant of citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States” did not apply to Indians born on tribal lands. Nevertheless, the policy was to encourage assimilation, and in 1924 — at a time when blacks were routinely kept from the polls in the south — Congress declared all Indians to be citizens and voters.

Women

Few people know that women were voting in American elections long before the 19th amendment was ratified in 1920. The original constitution of New Jersey let women vote, though the state took this right away in 1807. Here and there, propertied widows and unmarried women could vote in school-related elections, and women could vote in some Western states long before the 19th amendment.

The movement for women’s suffrage began in earnest in 1848 and was closely associated with abolitionists. Many early suffragettes assumed women would get the vote along with blacks, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, one of the movement’s hallowed founders, thought women should take precedence: “I would not trust him [the colored man] with all my rights; degraded and oppressed himself, he would be more despotic with the governing power than even our Saxon rulers are.” However, extending the vote to women would have brought to Republicans none of the political advantages of extending it to blacks, and the 15th amendment severed any connection between the two movements. Still, the abolition and votes-for-blacks campaigns were important training grounds for suffragettes, who built up increasingly powerful local movements.

The debate took many turns. Sometimes women argued they should vote because they were just as intelligent and sensible as men — essentially the same as men. They also argued that women should vote because women were different from men — more peaceable and caring. One suffragette even proposed that government was akin to housekeeping, and that natural housekeepers would be particularly good at it. Curiously, the opposing view was that the purity of women would be degraded by involving them in the dirty business of politics. It was also common to argue that voting would change sex roles and destroy the family. The liquor industry opposed votes-for-women for fear women would vote for prohibition. Rarely does anyone appear to have warned of what actually happened: that women would vote differently — more socialist — than men.

The thin edge of the wedge was the west. Wyoming territory gave women the vote in 1869 and did not take it back on becoming a state in 1889. Utah did the same in 1870 and 1896. Idaho and Colorado gave women the vote in the mid-1890s, at a time when eastern states were routinely defeating suffragette proposals. It is common to attribute this to some uniquely western broad-mindedness, but Prof. Keyssar supplies the corrective: Western states had large numbers of bachelor ranch hands and laborers. The propertied classes, who set the rules, were more likely to be married, and they gave their wives and daughters the vote in the hope this would counter the influence of landless drifters.

By the 1870s and 1880s, a common suffragette argument was that giving (white) women the vote would likewise counter the votes of blacks, Chinese, aliens, and other undesirables. In the south, activists argued that “Anglo-Saxon women” were “the medium through which to retain the supremacy of the white race over the African.” Southern women strongly supported literacy tests and poll taxes. However, some southern whites thought giving women the vote would make it harder to keep it from blacks. As a senator from Mississippi pointed out shortly after the turn of the 20th century, “We are not afraid to maul a black man over the head if he dares to vote, but we can’t treat women, even black women, that way.”

After about 1910, votes for women became associated with socialists and the left, and between 1910 and 1913 activists got the help of trade unions to secure women’s suffrage in California, Arizona, Kansas, Oregon, Illinois, and Washington.

By the First World War, suffragettes had a noisy, nation-wide movement. By then, there were so many women voting in so many states it became difficult for any party to take a position against it; it could be punished at the polls wherever women already voted. When the United States entered the war, women argued that although President Wilson claimed to be fighting for democracy he denied it to half the population. Women also helped on the home front and activists threatened to down tools if they did not get the vote. The 19th amendment passed the House in 1918 and the Senate in 1919. By then, suffragettes had well-oiled machinery in more than enough states for quick ratification.

Although property, sex, and race have been the main obstacles to voting, Prof. Keyssar approvingly describes the other barriers that have fallen. The 1972 amendment that lowered the voting age to 18 was yet another enthusiasm of the times, but the Vietnam-driven idea that draftees should be able to vote was not without opposition. Congressman Emanuel Celler of New York said: “To my mind the draft age and the voting age are as different as chalk and cheese. The thing called for in a soldier is uncritical obedience, and that is not what you want in a voter.” He added: “[The years of young adulthood] are rightfully the years of rebellion rather than reflection. We will be doing a grave injustice to democracy if we grant the vote to those under twenty-one.”

For Prof. Keyssar, there is still one piece of unfinished business in the glorious work of expanding the franchise. Most states still keep felons out of the voting booth, and Prof. Keyssar is distressed to find that they are disproportionately black. He has swallowed the view that this reflects “racism” rather than crime rates, and looks to the day when released jail-birds can vote again.

In what is inevitably an approving account of much progress, Prof. Keyssar does strike a warning about low rates of voter participation. In the 1830s and 1840s, he tells us, participation reached 80 percent, but today even a presidential election can draw only 50 percent of voters, and local elections only 20 to 25. Prof. Keyssar does not seem to realize that the very thing he celebrates — expanding the rolls — probably explains this. Blacks, women, and the propertyless vote less frequently than white men of means. It would be interesting to know the current voter participation rates of people who would have met the restrictions still in place in the 1830s.

Another question Prof. Keyssar completely ignores is the political effect of expanding the franchise. Blacks do not vote the same as whites, nor do women vote like men. What is the nature of these differences, and how do they effect elections? Prof. Keyssar no doubt approves of the effects, but to ignore them is almost to miss the very point of writing his book. Women, blacks, and beggars presumably wanted the vote because their vote would not be the same as those who already voted. Was what they wanted good for the country? Was it good even for them?

Prof. Keyssar seems to think expanding the franchise in every direction is so obviously good it would be pointless to study its consequences. It is precisely because it had consequences that people opposed it. Did they have good reasons? It is with the characteristic arrogance of his times that Prof. Keyssar does not even consider this question.

| IN THE NEWS |

|---|

O Tempora, O Mores!

More British Race Riots

Almost exactly a month after the town of Oldham went up in flames in the worst British race riots in 15 years, the nearby town of Burnley saw three days of street battles between Asians (mostly Pakistanis and Bangladeshis) and whites. The trouble began late Friday night, June 22, when Asians asked white neighbors to turn down the music at a noisy party. There was a standoff, with whites and Asians throwing bricks and rocks at each other, and an off-duty Asian taxi driver got a broken cheek bone.

The next day, rumors spread that the man had been beaten to death, and that police had been slow to help. Asians went into the street looking for trouble and met whites happy to oblige. Rioters battled each other and burned cars, and a mob of Asians broke out the windows of a pub they said was a “racist” hangout.

Sunday was even more violent. Asians poured into the streets after rumors whites were going to invade one of their neighborhoods. They burned down a pub and threw petrol bombs at the police. For two-and-a-half hours, riot police kept whites and Asians apart as they burned cars and looted stores. It took hundreds of officers and a helicopter overhead to keep mob violence from going into a fourth day.

On Wednesday, a car-load of Asians pulled up beside several whites and taunted them. The car pulled away but returned and ran down one of the whites. “This was a very dangerous incident and the victim suffered a broken leg, but he could have been much more seriously injured or killed,” said a spokesman for police, who consider the incident a racial assault. Two days later, in the nearby town of Accrington, the home of an Asian family was set on fire for what may have been racial reasons.

Burnley has a relatively small Asian population — about five percent — and did not have the reputation for tension that had put Oldham in the news months before the rioting began. Residents claim race relations had generally been good, but not any more. “We weren’t racists before, but we are now,” says a white woman who watched “a group of Pakis” set fire to a pub. The injured taxi driver is said to be so frightened he plans to go back to Pakistan.

Government ministers and city leaders tried to blame the fighting on the British National Party (BNP) and outside agitators, but police reported no evidence of this. Maria Coulton was landlady of the Duke of York, one of the pubs burned to a shell. “This is a racist attack on white people in my eyes,” she says. “I told the police I was afraid my pub was going to get torched and they assured me it wasn’t. The police said to stay put, and this is the result. I have absolutely nothing left. I have had to borrow clothes and shoes. My children have lost their toys.” She says that if she had not moved her children out of the pub in defiance of police assurances they would have died in the fire. “We just don’t know who to blame,” she says. “We vote Labour. We have never met anyone in the BNP.” [Ed Cropely, Noise Row at Root of English Race Riot: Minister, Reuters, June 25, 2001. Angelique Chrisafis, Years of Harmony Wrecked in Days, Guardian, June 26, 2001. Ed Johnson, British Police Prove Hit-and-Run, AP, June 27, 2001. Chris Hastings and Charlotte Edwardes, BBC Race Row Over Burnley Today Show, Electronic Telegraph, July 1, 2001.]

Last Judgment

Giovanni Da Modena was a 15th-century Italian painter, whose “The Last Judgment” graces a wall in the cathedral of San Petronio in Bologna. A group calling itself the union of Italian Muslims has launched a campaign against the priceless fresco because it includes a tiny representation of the prophet Mohammed being cast into hell. The group wrote a letter to the pope and to Cardinal Giacomo Biffi, Archbishop of Bologna, insisting that the “barbarous” fresco be taken down.

They sent their letter to the wrong Archbishop. Cardinal Biffi has been outspoken in his opposition to Muslim immigrants who, he says, do not assimilate. He calls them a threat to the values of Christian Europe, and has urged European governments to encourage counter-immigration from Catholic countries. As for the fresco, a spokesman says it is “absurd suddenly to discover after 600 years that our most famous treasure is offensive to the Islamic religion.” [Richard Owen, Muslims Say Fresco Must be Destroyed, Times (London), June 29, 2001.]

Fighting Back at Ford

John Kovacs, 36, has worked in personnel for Ford Motor Credit Co. since 1992. He saw so much blatant discrimination against white men that on March 13 he wrote a letter to Ford chairman, William Clay Ford, explaining that these practices are illegal. He got no reply. Instead, in early April he was suspended from his job and is now suing in Wayne County Circuit Court. His filing papers include many internal Ford documents that certainly give the impression of discrimination. Job openings were often designated “diversity candidate preferred” or “female candidate preferred.” Also, Ford had a system of “stretch” promotions, which meant someone moving up would require special assistance in the new job, and documents show white men never got “stretch” promotions.

For Mr. Kovacs the breaking point came during a November 13 meeting when a high-ranking personnel officer announced that in order to meet “diversity” goals, no more white men could be hired or promoted at management levels for the rest of the year. According to the minutes, this meant “delaying the hiring, promotion and referral of white males unless there is a good business case to bring them in by year end,” and also “the pulling ahead of any promotion, upgrades, referral etc. of non-white” candidates. It was Mr. Kovacs’ job to announce this new policy to management, and he couldn’t bring himself to do it.

Ford recognizes the high stakes in this case, and is fighting it on every front. “Ford’s best hope is to make it so miserable for this guy that he goes away or he settles,” says Ken Kovach, a professor of industrial relations at George Mason University. Mr. Kovacs swears he will fight to the end. [Mark Truby, Whistleblower Takes on Ford, Detroit News, July 1, 2001.]

Gruesome Prescription

On June 7, a federal district judge approved a $192.5 million settlement in a class-action discrimination suit filed against Coca-Cola by black employees, each of whom will receive an average of about $38,000. Now, as part of the settlement, the company has hired an outside committee to which it must submit all personnel policies and decisions. The list of members reads like the all-star team for racial preferences. Chairing the committee is Alexis Herman, a black woman who was William Clinton’s Labor Secretary, and whose confirmation was nearly derailed by corruption charges. Another member of the committee is Bill Lann Lee, former Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights at the Clinton Justice Department. Mr. Lee is perhaps the most fanatical supporter of discrimination against whites ever to hold that job. Other members whose views are easy to guess are Gilbert F. Casellas, former chair of the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and Rene Redwood, who was executive director of the federal Glass Ceiling Commission that investigated alleged job discrimination against women. The other two members are M. Anthony Burns, chairman of Ryder System Inc., the Miami rent-a-truck company, and Marjorie Knowles, former dean of Georgia State University College of Law. Their ardor for race preferences is not so well known, but by all appearances Coca-Cola has hired a group of people who will make sure the company practices precisely the kinds of discrimination for which Ford Credit is being sued. Douglas Daft, Coca-Cola’s chairman and chief executive, claims to be ecstatic: “With this group of distinguished, committed individuals on board, I am very pleased that the task force will soon be able to begin working with us to accelerate the company’s progress on this vital front.” [Justin Bachman, Task Force to Oversee Coke Hirings, AP, July 2, 2001.]

Law Among the Blacks

Until recently Gene Gardner was police chief of the largely-black town of Midway, Florida. In April, he was arrested after a federal investigation determined he had been selling confiscated weapons and other seized property, and pocketing the money. Mr. Gardner hawked off so much merchandise he was able to convert one evidence room into a “lounge area.” When an officer asked what happened to all the evidence, he is reported to have said, “Sold, brother, sold.” Mr. Gardner’s lawyer, also black, says no crime was committed because Mr. Gardner did not realize what he was doing was illegal. “The evidence will show,” he argues, “there was no wrongdoing intentionally done,” so his client should go free. [James Rosica, Chiefs Never Meant to Break the Law, Tallahassee Democrat, June 19, 2001.]

Preserving the Latino Core

The Lindbergh area of Atlanta has rising land prices that make it attractive for redevelopment. A group of apartment complexes built for young couples who came to Atlanta just after the Second World War is likely to be replaced soon with high-rise condominiums and fancy shops. The only obstacle appears to be that since the 1960s the apartments have been occupied by blue-collar Hispanics, many of them from Cuba. In a recent front-page story, the Atlanta newspaper wrote lovingly about the area, and quoted Teodoro Maus, the former consul general of Mexico: “If it’s lost, we are going to lose a lot more than just some apartments. This would be a great place for maintaining what its character should be.” Mr. Maus went on to say: “Lindbergh is not just those apartments for Latinos. It’s a whole concept. It’s a Latino core. There’s a character there.”

Miguel Fernandez, 89, who has lived in the same Lindbergh apartment for the last 31 years explains why it would be a tragedy for the renters to be scattered by redevelopment: “Spanish-speaking people prefer to be around other Spanish-speaking people. It’s more comfortable.” Somehow we cannot imagine a similarly sympathetic article about the imminent disappearance of any white neighborhood anywhere in America. [D.L. Bennett, Lindbergh Boom Puts Latino Enclave at Risk, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, July 2, 2001, p. 1A.]

Trouble in Paradise

The French island of St. Martin in the Caribbean is a well-run little corner of overseas Europe. Now, lured by permissive attitudes, such as allowing anyone to enroll in the local schools no questions asked, it is overrun with illegal aliens. French officials now estimate that illegals outnumber natives, and newcomers have brought crime and other problems that threaten the island’s number one industry: tourism. “We need to consider that it is impacting this little island and the economy and the society so badly that something will have to be done,” says Daniella Jeffry, a leading political figure. “The unemployment rate is very high, it goes up to 30 percent,” she adds.

Illegals happily send their children to the excellent public schools. “Of course it presents a problem because of the various origins of these people and their various linguistic backgrounds,” says Frantz Gumbs, the vice-principal of Marigot College. “Spanish for those coming from the Dominican Republic, English for those coming from the British Commonwealth and Creole for those coming from Haiti.” The students put the problem more bluntly: “We have too much violence and fighting and everything,” says one girl. “With knives, guns — everything,” adds another. [Jon Sopel, Caribbean Island Attracts Illegal Immigrants, BBC, June 26, 2001.]

‘Testing’ Diversity

Asian students in New York City are upset that the state of New York scheduled this year’s Regent English exam on January 24. “Couldn’t they have picked a better day for the test than the Chinese New Year?” asked Michael Kwon, a senior at Stuyvesant High School. Mr. Kwon and 500 other students circulated a petition to have the date of the exam changed out of sensitivity to Asian culture. The exam went ahead as scheduled, but the state will try to do better next year. “We have to be very sensitive to calendars and holy days that people celebrate,” said Rowena Karsh, deputy superintendent for high schools in Queens. “Everyone has a different day and a different way they celebrate.” [Leonard Greene, Cultural Holidays Pose Big Problem, New York Post, April 8, 2001.]

Tipping the Scales

Immigrants are flocking to Miami-area Publix supermarkets, but not to buy groceries. Instead they throw luggage on the free scales the supermarkets set out so customers can weigh themselves. The idea is to avoid excess-baggage charges on goods immigrants plan to take back to relatives when they fly home for vacation — airlines have special baggage surcharges on summer flights to South America and the Caribbean. Hispanics haul suitcases, garbage bags, boxes and duffel bags to the stores and load them on the scales. If there is an excess they pull things out and repack right in the front of the store.

“We’re frustrated,” said Carmen Millares, community affairs manager for Publix’s Miami division. “The scales are for people, not for suitcases. They were made to be stepped on gently. When people toss heavy bags on them, they break them.” Publix is considering putting up signs that prohibit luggage weighing, or removing the scales entirely. When asked why the Hispanic immigrants weigh their luggage at white-owned Publix rather than at Sedano’s, a Hispanic South Florida grocery chain, a spokesman for Sedano’s said their scales “cost a quarter and they’re not that accurate.” [Annabelle de Gale, Publix Scales Prove Too Tempting for Travelers, Miami Herald, June 24, 2001.]

Corporate Folly

The newest board member of Sears, Roebuck and Co. is Raul Yzaguirre, president of the National Council of La Raza. La Raza, which means “the race” in Spanish, is a Hispanic advocacy group, heavily funded by liberal foundations, and champions affirmative action, bilingual education, mass immigration, and more hate crime laws. It claims immigration control violates civil rights, and described the 1996 effort by Congress to cut back on handouts to immigrants as “a disgrace to American values.” In announcing Mr. Yzaguirre’s appointment to the board, Sears Chairman and CEO Alan J. Lacy said, “Raul Yzaguirre’s experienced leadership will bring a valued perspective to the business opportunities and public policy issues we face today.” [La Raza Press Release, June 7, 2001.]

Supreme Folly

On June 18, the Supreme Court let stand an appeals court ruling that overturned the murder conviction of Wilbert Rideau, a confessed bank robber and murderer, because the Louisiana grand jury that indicted him had only one black on it. The appeals court ruling concluded this was racial bias — contradicting two state rulings. Mr. Rideau had appealed in state court on the same grounds back in the 1960s but the Louisiana Supreme Court twice found no evidence blacks were excluded from the grand jury. The current ruling came as a result of a 1994 federal habeas corpus appeal.

Mr. Rideau, who has celebrity status as a “prison journalist” and claims to be “the most rehabilitated prisoner in America,” has been in jail for the past 40 years for murdering a white bank teller and wounding two hostages during a Louisiana robbery in 1961. He shot the teller and then stabbed her and cut her throat when she tried to crawl away. He must either be tried again within a reasonable period or set free, but Louisiana authorities are afraid that after 40 years it will be impossible to put on a convincing case. Mr. Rideau has already had three trials, and been sentenced to the electric chair every time. His sentence was changed to life imprisonment in the 1970s when the Supreme Court overturned the death penalty. [James Vicin, US High Court Sides With Prison Journalist on Bias, Reuters, June 18, 2001.]

Rubie Lee Mandy is a black who worked at REM Oak Knoll, a group home for adults with mental problems, in White Bear Lake, Minnesota. One day the home’s van disappeared, and the garage was spray-painted with anti-black graffiti. Miss Mandy told police four whites had shouted racial slurs at her the day before. When police recovered the vehicle, which had been similarly defaced, they noticed the steering column showed no signs of the tampering necessary to operate it without a key, and that it had been damaged in an accident. Police started investigating the employees of the group home, where the only key was kept. Miss Mandy confessed to police she had damaged the van while joyriding, and then painted the racist graffiti and concocted the story about the slurs in order to cover her trail. She is charged with motor vehicle theft and first degree criminal damage to property. [Cynthia Boyd, Woman Who Claimed to be Victim of Hate Crime Accused of Stealing Van, St. Paul Pioneer Press (Minnesota), June 12, 2001.]

Not Bulletproof

We reproduce this dispatch, unedited, from the Reuters News Service:

A Ghanaian man was shot dead by a fellow villager while testing a magic spell designed to make him bulletproof, the official Ghana News Agency reported on Wednesday.

Aleobiga Aberima, 23, and around 15 other men from Lambu village, northeast Ghana, had asked a jujuman, or witchdoctor, to make them invincible to bullets.

After smearing his body with a concoction of herbs every day for two weeks, Aberima volunteered to be shot to check the spell had worked.

One of the others fetched a rifle and shot Aberima who died instantly from a single bullet.

Angry Lambu residents seized the jujuman and beat him severely until a village elder rescued him, the report added.

Tribal clashes are common in Ghana’s far north, where people often resort to witchcraft in the hope of becoming invulnerable to bullets, swords and arrows. [Reuters, Ghana Man Shot Dead as Bulletproof Magic Fails, March 15, 2001.]

Bowdlerized Bugs

The Cartoon Network recently planned a retrospective of every Bugs Bunny cartoon ever made, but got cold feet and cut about a dozen that were “insensitive.” In one, Bugs distracts a black rabbit-hunter by rattling a pair of dice, and in another he parodies Al Jolson. Network executives also cut a cartoon in which Bugs calls an oafish, bucktoothed Eskimo a “big baboon.” [Bugs Bunny Retrospective Coming, AP, May 2, 2001.]

Poetic Justice

In a recent statewide referendum, Mississippi voters overwhelmingly elected to keep their state flag, of which the Confederate battle flag is a prominent part. The same choice was denied the people of Georgia when earlier this year, Governor Roy Barnes (D) and a black-white liberal coalition of state legislators — citing NAACP boycott threats — decided to change the flag themselves, without input from the public. The new flag, in which the battle flag has been demoted to the size of a postage stamp, is widely derided outside corporate offices of Atlanta, and has finally gotten the kind of respect it deserves. Members of the North American Vexillological Association (study of flags) have declared the new Georgia flag the ugliest in North America. In an on-line survey, the “Barnes flag” came in dead last among the 72 state, provincial and territorial flags of the United States and Canada. “It was the only flag people said “I wish I could give negative points to,’” said Ted Kaye, who compiled the survey. [Dan Chapman, Experts Vote Georgia’s Redesigned Flag “the Ugliest’ — By Far, Atlanta Constitution, June 21, 2001, p. C-1.]

Walking Away MAD

The National Association of Minority Auto Dealers (NAMAD) is a group that tries to get more car dealerships for non-whites and to get better terms for existing dealers. It has traditionally pushed the interests of blacks, and Hispanics are tired of sitting in the back of the bus. NAMAD was “founded by blacks for blacks,” says Silvestre Gonzales, a Daimler Chrysler dealer in California who is leading a breakaway group to be called the Hispanic Auto Dealers Association. He says the defection is rooted in “the frustration of the Hispanic community that has been growing for 20 years.” George Mitchell, a black Ford dealer from Tennessee, thinks the Hispanics are Johnny-come-lately cry-babies. He says he is “old enough to remember the civil-rights movement, the genesis of where we are today.” “I remember when the fighting was going on,” he adds. “Where were they?”

NAMAD has been slow to elect any of its growing number of Hispanic members to executive positions. Martin Cumba was the first, joining the 20-member board in 1994. He says he had tense moments with black board members but thinks Hispanics should stay in NAMAD and present a united front to the white man. He says automakers will be better able to “divide and rule” if there is more than one non-white organization. [Linda Bean, Civil War? Some Hispanics Secede From Minority Auto Dealers’ Group, DiversityInc.com, March 12, 2001.]

Aborting Crime?

In a recent study, John J. Donohue of Stanford Law School and Steven D. Levitt of the University of Chicago, support the view that the legalization of abortion in the early 1970s may be partly responsible for the drop in crime in the 1990s. The authors cite studies that indicate unwanted children are twice as likely to be criminals as those who are wanted. As Prof. Levitt explains, “a difficult home environment leads to an increased risk of criminal activity. Increased abortion reduced unwantedness and therefore lowered criminal activity.” Children of poor teenage mothers, unmarried women and black women — all of whom have above-average rates of abortion — are more likely to commit crimes when they grow up. [Alexander Stille, New Attention for the Idea That Abortion Averts Crime, New York Times, April 14, 2001.]

IQ and Life Expectancy

Scottish researchers have discovered a possible link between IQ and life expectancy. While following up on an intelligence test given to more than 2,000 eleven-year-olds in 1932, they found that the average IQ of those who had died by January 1, 1997 was 97.7, compared to 102 for those still living. A score 15 points below average meant a 20 per cent less chance of surviving to age 76, while those 30 points below average were 37 per cent less likely to live that long. [Celia Hall, People with High IQs “Live Longer,’ Electronic Telegraph (London), April 6, 2001.] IQ differences may help explain longevity differences between the races, with higher-IQ Asians and whites living longer on average than blacks.

White Cops Claim Bias

Seven white Chicago police supervisors have filed a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, accusing their district commander, Marienne Perry, of discrimination against whites. They say Commander Perry favors black officers for promotion, unfairly launches internal investigations against whites, and uses racially inflammatory language. “She’s gone so far as to make statements that when people of the 2nd District walk into this station, they expect to see a black face,” said Jeff Wilson, president of the Chicago Police Lieutenants Association. Mr. Wilson believes Marienne Perry is one of several black police commanders who have been “promoted beyond their competency level because of pressure to increase minority participation.” Commander Perry denies charges of discrimination, and senior police officials attribute the friction to Perry’s management style, but white officers are transferring out. Seven white police lieutenants have left the district in the past 19 months, as have two white desk sergeants. [Frank Main and Fran Spielman, White Cops: Black Boss Biased, Chicago Sun-Times, April 13, 2001.]

De-Policing Seattle

Stung by accusations of racial profiling, police in Seattle are doing exactly what one would expect: backing off from enforcing the law against blacks. Police Chief Gil Kerlikowske acknowledges there is “de-policing,” but denies it is widespread. His men aren’t so sure. “It’s real. It’s happening,” says Eric Michl, a patrol officer for 17 years. “Parking under a shady tree to work on a crossword puzzle is a great alternative to being labeled a racist and being dragged through an inquest, a review board, an FBI and US Attorney’s investigation and a lawsuit.”

Officer Michl, who is white, says he recently pulled over a black man who was driving without a license or registration and seemed high on cocaine. “If he were any other race, I would have probably arrested him on the spot,” he says. “But then I started thinking, “What if he’s on cocaine, what if we get in a fight and he dies, and then we find out he’s only guilty of a suspended license.’ I don’t want to see my name in the papers.” Officer Michl went back to his police cruiser to request a background check on the car, and the suspect fled. The car turned out to be stolen, and the man was captured later, but Officer Michl is annoyed he can’t follow his instincts. “There are a lot of us who are extremely frustrated about this,” he said.

Black officers are frustrated, too. Al Warner, who is black, recently caught four black men smoking marijuana in a car. They accused him of racially profiling them. “It’s the catch phrase now,” he says. “If I were an African-American drug dealer here, that’s the way I’d play the game. It intimidates officers.” Another black police officer, Tyrone Davis, says police are reluctant to use force of any kind for fear of starting a brawl.

De-policing has already had deadly results. During the Mardi Gras riots in February, police brass held officers back for fear television images of police battling black rioters would be broadcast nationwide “It wouldn’t have looked good,” explains Officer Michl. There were dozens of assaults, and blacks beat a white man to death during several hours of deliberate de-policing.

Officers see the racial profiling debate as a pointless distraction from their jobs. “It’s a ghost. It’s a phantom” says Ken Saucier, a black policeman with 16 years on the force. “As long as you can get people chasing the smoke, you won’t have to deal with the real problem.” The real problem, according to Officer Saucier and other policemen, is black crime. They cite U.S. Department of Justice statistics that show black men, only six percent of the population, commit 40 percent of violent crime. They say it only makes sense to put more police in black areas. It is the people who live there who are hurt most when de-policing means less law-enforcement and more crime. Says Officer Saucier of black agitators who want to stamp out racial profiling: “Be careful what you wish for because you might get it.” [Alex Tizon and Reid Forgrave, Wary of Racism, Police Look the Other Way in Black Neighborhoods, Seattle Times, June 26, 2001.]

No Hate in Patterson

Patterson, New Jersey, is a city of about 149,000 that is half Hispanic and one-third black. Students at John F. Kennedy High School reflect this ethnic mix, and administrators have started “conflict resolution” and “peer counseling” programs to curb racial violence. On June 20, police had to break up a fight between young blacks and Hispanics near the school. Shortly afterwards, blacks swarmed through the streets and came across 42-year-old Hector Robles, a homeless Hispanic man. According to witnesses, they took his beer bottle and smashed him over the head with it before beating him to death. “They kicked him like a dog,” says his sister Miriam. “It looks to me like it was a racial thing. It was only blacks and he was Hispanic.” Police have arrested eleven blacks, ages 15 through 17, for the murder and may try them as adults. News of the killing has increased racial tension in this drab industrial city, but prosecutor Robert Corrado doesn’t think race was a motive. “From what we’ve gotten, it hasn’t even been mentioned,” he says. [Wayne Parry, Homeless Man Killing Stirs Concern, AP, June 25, 2001.]

| LETTERS FROM READERS |

|---|