July 2004

| American Renaissance magazine | |

|---|---|

| Vol. 15, No. 7 |

July 2004

|

| CONTENTS |

|---|

Brown v. Board: The Real Story

Brown and the Constitution

O Tempora, O Mores!

Letters from Readers

| COVER STORY |

|---|

Brown v. Board: The Real Story

We celebrate tragedy as if it were victory.

May 17 marked the 50th anniversary of the US Supreme Court’s famous ruling in Brown v. Board of Education. This decision, which forbade racial segregation in schools, is now being celebrated as a historic act of justice and courage. Of the hundreds if not thousands of public officials and editorial writers who have celebrated this anniversary, practically no one has criticized the decision. In fact, there is much to criticize. Brown was certainly one of the most important Supreme Court decisions of the 20th century; it is necessary that we know what was wrong — dreadfully wrong — about how it was decided, and what it brought about.

May 17, 1954 – Washington , District of Columbia, Thurgood Marshall (C) and fellow attorneys George Hayes (L) and James Nabrit rejoice outside the Supreme Court after the winning decision ruling out school segregation in Brown vs. Board of Education. (Credit Image: © Keystone Press Agency/Keystone USA via ZUMAPRESS.com)

First, the decision involved nothing less than collusion between one of the justices and his former clerk, who was handling the US Government’s arguments. One side of the case therefore had utterly improper inside knowledge about what every justice thought, and could craft arguments specifically to appeal to them.

Second, one of the key expert witnesses for desegregation — the only one singled out for praise in the ruling — deliberately suppressed research results that undermined his position. He certainly knew about these inconvenient results, because they were his own.

Third, because the Court could find no Constitutional justification for overturning the doctrine of “separate but equal,” it based its ruling on then-fashionable sociological theories. These theories were wrong.

Fourth, Brown was the first fateful step towards what we call “judicial activism.” The Supreme Court set aside its obligation to interpret the Constitution, and did what it thought was good for the country. It inaugurated an era of, in effect, passing new laws, rather than interpreting old ones. Judicial orders should never preempt law-making by elected representatives; republican government has been badly eroded by the process set in motion by Brown.

Finally, integration orders were among the most intrusive and damaging ever issued by American courts. Judges took over the most minute school-related decisions as if they were one-man school boards. Mandatory racial balancing — usually accomplished by busing — provoked white flight that in many cases left schools even more segregated than before. Beginning in 1991, the Court eased its requirements for mandatory busing, but by then it had already caused incalculable dislocation and had turned most big-city school districts into minority ghettos.

The final reckoning of Brown has yet to be made, but it is a ruling to be mourned, not celebrated.

How Brown Came About

Until Brown, the best known Supreme Court ruling on racial segregation had been Plessy v. Ferguson, handed down in 1896. This case involved separate railroad coaches for black and white travelers, and the court ruled famously that segregation was constitutional so long as the races were accommodated in a “separate but equal” manner.

Separate was not always equal, however. In 1930, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and Louisiana spent about one third as much on each segregated black public school student as on each white student. South Carolina, the most extreme case, spent only one tenth. Whites justified this difference by pointing out that local taxes paid for schools, and that blacks paid far less in taxes than whites.

Spending on black schools increased rapidly in the 1940s and 1950s, often because of NAACP lawsuits insisting that if black schools were to be separate the Constitution required that they be equal. Many judges agreed, and throughout the old Confederacy there was a flurry of new taxes and bond issues to raise money for black schools. By the 1950s, the gap had been greatly narrowed all across the South, and in Virginia, for example, expenditures, facilities, and teacher pay were essentially equal in the two systems. Whites did not want to send their children to school with blacks, and were prepared to make considerable sacrifices to avoid doing so. Some within the NAACP wondered whether forcing the South to live up to the requirements of “separate but equal” would only make segregation permanent.

Nevertheless, the Supreme Court agreed to hear the Brown case, which was a direct attack on separate school systems, even if they were equal. It was a consolidation of five separate cases that had arisen in different states, and petitioned the Court to abolish segregated schools on the basis of the “equal protection” clause of the 14th Amendment.

It was impossible, however, to argue that the original intent of the 14th Amendment was to forbid segregated schools. The same Congress that passed the Amendment in 1866 established segregated schools in the District of Columbia, and after ratification two years later, 23 of the 37 states either established segregated schools or continued to operate the ones they already had. Chief Justice Frederick Vinson was particularly bothered by a Constitutional appeal that required the Court to recast the meaning of an Amendment.

During oral arguments in the case in December 1952, Thurgood Marshall of the NAACP therefore did not make a legal argument. His case rested on what came to be known as the “harms and benefits” theory, that segregation harms blacks and integration would benefit them. Justice Robert Jackson, who had been chief prosecutor of Nazi war criminals at Nuremberg, complained that Marshall’s case “starts and ends with sociology.” He did not support school segregation but thought it would be an abuse of judicial power to abolish it by decree. “I suppose that realistically the reason this case is here is that action couldn’t be obtained from Congress,” he noted.

In fact, the sociology with which Marshall started and ended was weak. He leaned heavily on the work of Kenneth Clark, a black researcher known for doll studies. Clark reported that if he showed a pair of black and white dolls to black children attending segregated schools and asked them which doll they liked better, a substantial number picked the white doll. He argued to the Court that this proves segregation breeds feelings of inferiority. He failed to mention that he had shown his dolls to hundreds of blacks attending integrated schools in Massachusetts, and that even more of these children preferred the white doll. If his research showed anything, it was that integration lowers the self-image of blacks, but he deliberately slanted his findings.

John W. Davis, the lawyer who argued to retain segregated schools, pointed out that Clark’s conclusions contradicted his own published results in the Massachusetts findings. Davis later told a colleague that the ruling would surely go his way “unless the Supreme Court wants to make the law over.”

If the Court had decided the case immediately after oral arguments, Brown might have been decided the other way or at best, with a five-to-four majority that would have given it little authority in the South. It was at this point that Justice Felix Frankfurter, who was desperate to end segregation, assumed a key role. Faced with a bad legal case and justices who did not want to abuse their power, his strategy was to delay. He argued strongly that a decision on Brown should be put off to allow time for an investigation of the original intent of the 14th Amendment and to let the new Eisenhower administration take a position. In the meantime, without telling the other justices, he told his clerk, Alexander Bickel, to ransack the history of the Amendment in the hope of finding something that would justify striking down segregation.

In June 1953, the Court put Brown back on the docket and invited the new administration to file a brief. Eisenhower’s people wanted to stay out of the controversy entirely, but unbeknownst to them an agent for Felix Frankfurter was working at a high level in the Justice Department. Philip Elman had clerked for Frankfurter, and was in constant communication with his old boss about Brown. He told the Solicitor General that a Supreme Court invitation to comment on a case was like a command performance, and he offered to handle the case.

Elman and Frankfurter both knew that back-channel communication was wrong. A party to a case is never permitted to have secret discussions with a judge who will decide his case. In a long 1987 article in the Harvard Law Review, in which he described in detail the collusion that went into the Brown ruling, Elman conceded that what he did “probably went beyond the pale” but, he added, “I considered it a cause that transcended ordinary notions about propriety in a litigation.” He wrote that he and Frankfurter kept an appropriate professional distance on all other cases, but made an exception for Brown. To them, ending school segregation was so important it justified unscrupulous maneuvering.

They talked at length over the phone and in person, referring to the other justices by code. William Douglas was Yak because he was from Yakima, Washington. Stanley Reed was Chamer, because it means dolt or mule in Hebrew, and Reed thought desegregation was a political and not a judicial matter.

In September 1953, something happened that completely changed the complexion of the Court: Chief Justice Frederick Vinson, a strong opponent of judicial activism, suddenly died. As Elman reports in the 1987 article, Frankfurter met him soon after in high spirits. “I’m in mourning,” he said with a huge grin. “Phil, this is the first solid piece of evidence I’ve ever had that there really is a God.” Elman writes that “God takes care of drunks, little children, and the American people” and showed His concern for America “by taking Fred Vinson when He did.” The new Chief Justice was Earl Warren, an ambitious former governor of California, who saw his job not as interpreting the Constitution but as a chance to exercise power.

In the meantime, Frankfurter’s clerk Bickel could find nothing in the history or intent of the 14th Amendment that could be used to order desegregation, so Frankfurter changed tack. He began to urge that original intent did not matter, and that the Amendment’s language should be reinterpreted according to the needs of the time. He reported to Elman that Warren and some of the other justices were sympathetic to this view, so not surprisingly, when the Justice Department filed Elman’s 600-page brief in December 1953, it too argued that the language of the Amendment was broad enough to be reinterpreted.

The reargument covered the same ground as before. Marshall trotted out the bogus doll studies again, while the Justice Department echoed Bickel’s view that the original intent of the 14th Amendment could be ignored. Frankfurter wrote long memos to the other justices insisting that the law must respond to “changes in men’s feelings for what is right and just.” This combination of arguments overcame the scruples of most of the justices who were reluctant to go beyond what they considered to be the limits of their authority. Jackson and Reed were the only holdouts. The former Nuremburg prosecutor refused to dabble in what he thought was a political rather than a judicial matter, and Reed, the chamer, argued that judicial activism was the beginning of “kritarchy,” or rule by judges.

At the end of March 1954, Jackson suffered a serious heart attack. Warren rushed to the hospital and got the weakened justice to agree to the opinion he had drafted. Then he cornered Reed, telling him he would be all alone if he did not go along. Reed, who never agreed with the ruling, bowed to pressure and joined the majority.

On May 17, Warren read the decision from the bench. Since there was no legal reasoning involved in it, he could keep it short enough to make the entire ruling fit into a newspaper article. The most often quoted passage is the following:

To separate [black children] from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely to ever be undone . . . We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.

Warren admitted that he was interpreting the Constitution differently from every Supreme Court that had gone before:

“[W]e cannot turn the clock back to 1868 when the [14th] Amendment was adopted, or even to 1896 when Plessy v. Ferguson was written,” he argued. The point to be addressed was whether “segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race, even though the physical facilities and other ‘tangible’ factors may be equal, deprives the children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities.” His conclusion: “We believe it does.” As evidence, he cited Clark’s doll studies.

It should not require pointing out that whether segregation makes blacks feel inferior is not a Constitutional issue. Even if the evidence that segregation did have that effect had been solid — and it was not — it did not justify reinterpreting the Constitution.

Even liberals recognized that the Court was practicing sociology and not law. The New York Times, which welcomed the ruling, nevertheless gave its May 18 article the following sub-headline: “A Sociological Decision: Court Founded Its Segregation Ruling On Hearts and Minds Rather Than Laws.” The dean of the Yale Law School, Wesley Sturges, put it more bluntly. For the justices to rule as they did, he noted, “the Court had to make the law.”

Nor was Philip Elman’s behind-the-scenes role in the matter finished. The Constitution has been consistently interpreted to mean that the rights it grants are personal and require immediate relief. If segregation was unconstitutional it meant black students were entitled to integration right away. Frankfurter had explained to Elman that if this were what a desegregation ruling required, he could not be sure of getting unanimity, perhaps not even a majority. The prospect of the chaos such a ruling would cause would have pushed many justices into opposition.

It was Elman, therefore, who proposed the very unusual solution of separating enforcement from constitutionality. After the famous May 17 ruling, the Supreme Court sent the case back for further argument on how the decision should be implemented. It waited nearly a year, until May 1, 1955, to let the 1954 ruling sink in, before issuing another ruling on how to do what the Court ordered. It is here that we find the famous linguistic fudge: desegregation was to be accomplished with “all deliberate speed.” The South was going to have to abide by the Constitution, but it could drag its feet. “It was entirely unprincipled,” Elman wrote in 1987; “it was just plain wrong as a matter of constitutional law, to suggest that someone whose personal constitutional rights were being violated should be denied relief.” “. . . I was simply counting votes in the Supreme Court,” he added. Elman proposed a solution he concedes was “entirely unprincipled” because that was what it would take to get the ruling he and Frankfurter wanted.

In his article Elman also showed considerable contempt for Thurgood Marshall, who later became the first black appointed to the Supreme Court. He wrote that Marshall made bad, ineffective arguments, but that Elman’s collusion with Frankfurter had so rigged the Court in favor of desegregation, it made no difference: “Thurgood Marshall could have stood up there and recited ‘Mary had a little lamb,’ and the result would have been exactly the same.”

From Desegregation to Integration

The initial impact of the Brown decisions was, with a few exceptions, anti-climactic. The implementation order of 1955 applied only to schools that practiced legal segregation, and required only that they stop assigning students to schools by race. The targets were therefore only Southern schools, where there was little change, since most students stayed where they were. A few ambitious black parents enrolled their children in white schools, but no whites switched to black schools. There was dramatic resistance in 1957 to the arrival of even small numbers of blacks at Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, but desegregation — the end of forcible separation of students by race — passed easily enough. It was the shift from desegregation to integration — the obligatory mixing of students to achieve “racial balance” — that convulsed the country.

In Brown, the Supreme Court endorsed the view that it was legally enforced, de jure segregation that damaged the minds of blacks; the justices said nothing about the de facto school segregation that reflects residential segregation. However, as the 1960s wore on, and summers were punctuated by riots in New York, Rochester, Watts, and Newark, official thinking began to change. In 1967, the US Commission on Civil Rights issued a report called Racial Isolation in the Public Schools, in which it declared flatly that voluntary segregation was just as harmful as legally enforced segregation.

By now, almost all sociologists embraced the harms and benefits theory of desegregation, and endorsed the commission’s report rather than a much more thoroughgoing one that had appeared the year before. This was the now-famous Department of Health Education and Welfare study known as the Coleman report, officially titled Equality of Educational Opportunity. Sociologist James Coleman and his colleagues had fully expected to find that poor black academic performance was caused by inadequate school funding, and that integration brought black achievement up to the level of whites. They were surprised to learn that although there were regional differences — the North spent more money on schools than the South — within the regions school authorities were devoting much the same effort to blacks as whites.

Another surprising finding was that the amount of money spent on schools did not have much effect on student performance, and blacks who attended predominantly white schools did only slightly better than those who attended all-black schools. (Coleman later concluded that this small difference was not due to integration. The first blacks who attended white schools voluntarily were smart, ambitious blacks who would have done well in all-black schools.) These findings ran so contrary to ‘60s-era thinking that Coleman and his co-authors buried its conclusions, and the report became well-known only in retrospect.

In 1968, the Court adopted the more fashionable thinking of the Civil Rights Commission. In Green v. New Kent County, it ruled that race-neutral school policies were not good enough. At least for schools that had practiced de jure segregation, the “vestiges of segregation” had to be eliminated by race-conscious remedies and forcible integration. One likes to imagine the deliberations of our highest court conducted in Olympian calm, undistracted by mundane outside events. However, it may not be a coincidence that Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated the day after oral arguments in Green, and the Court deliberated during the worst race riots the country had ever seen.

Still, every court order so far had been directed to schools in the once-segregated South. The rest of the country could look on in smug superiority as Southern whites battled busing, set up private schools, fled to the suburbs and, in some cases, even closed down public schools rather than submit to “racial balancing.” At least in the South, whites clearly did not like forced race-mixing, and would go to great lengths to avoid it. To the elites of the time, this was precisely the kind of prejudice busing was designed to cure.

It is easy to lose sight of just how radical a change the courts required when they shifted from desegregation to forcible integration. A movie theater, for example, is considered desegregated if patrons of all races can attend. Depending on location, some theaters may have patrons of mostly one race or another, but no one would think of controlling the flow of customers in order to achieve “racial balance.” This, however, was the effect of the new Court rulings. It was as if blacks and whites had to check with a central authority whenever they wanted to see a movie, and were directed only to theaters across town where they were sure to be a racial minority. Imagine the resistance to rules of that kind applied to restaurants, libraries, sports events, etc. It is not surprising that Southerners resisted busing.

The respite for the North was short-lived. In its 1971 ruling in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education the Court decided that if forcible integration was necessary to correct the damage racial separation caused to Southern blacks, it was equally necessary in the North, where residential and school segregation were often almost as pronounced. The Court made it clear that integration was to apply to every aspect of a school, including teachers, staff, extracurricular activities, attendance boundaries for schools and new construction. The judges chose schools as the institutions that would henceforth make up for the effects of voluntary residential segregation, and breed a new generation that would ignore race. Soon parents everywhere were faced with the prospect of putting their children on buses for lengthy rides across town so blacks could attend white schools and vice versa. Whites in the North set about with a will to achieve racial balance but found that, if anything, they disliked busing even more than Southerners did.

Wilmington, Delaware, made a particularly ambitious effort. Courts consolidated all city and suburban school districts — so that whites could not escape to nearby white school districts — and ordered every school integrated. This was to be done by racial mixing in neighborhoods if possible, and otherwise by sending whites to the inner city and inner-city blacks to the suburbs.

Wilmington worked very hard to prepare for what everyone knew would be a wrenching change. For teachers, the days of the three Rs were over: They would have to make children feel important, and teach them how to cooperate. White teachers had to learn “empathetic listening,” “values clarification,” and “consultation skills,” so they could handle black children. Altogether, teachers got a very confusing message: The classroom would integrate black children into the American mainstream, but it must not transmit oppressive, middle-class values.

Like other school districts, Wilmington learned that any racial balancing plan causes white flight, but some plans cause more than others. Shipping white children out of their neighborhoods to black schools was the worst. About half the white parents did not even wait to see what it was going to be like; their children disappeared to the far suburbs and into private schools, and never set foot in a black school. Most of the rest abandoned the experiment soon thereafter.

Blacks were less unwilling to come to white schools, but this did not lead to racial mixing. As one Wilmington reporter noted, “despite the massive effort to bring the races together, students and even teachers segregated themselves at lunch, in the hallways, and in the classrooms if they were given the opportunity.” Administrators also discovered “the tipping point.” A few blacks did not change the character of a school, but as their numbers increased so did racial tensions. “It was almost as if there was something magic — or hellish — when the black enrollment reached 40 percent,” recalled Jeanette McDonald, who was dean of girls at P.S. du Pont High School. “The black attitudes changed then, and the whites had reason to be frightened.” Blacks would begin to extort protection money from whites, graffiti would appear, windows would be smashed, lockers were looted, and refuse would accumulate. An all-white school would rapidly begin to turn black. Once most of the whites were gone, those who remained adapted to black dominance.

Before Brown, Wilmington public schools were 73 percent white. By 1976, after forced busing, they were 9.7 percent white. Furious whites were hardly mollified when Federal Judge Murray Schwartz, one of the architects of the busing plan, transferred his own children to private school.

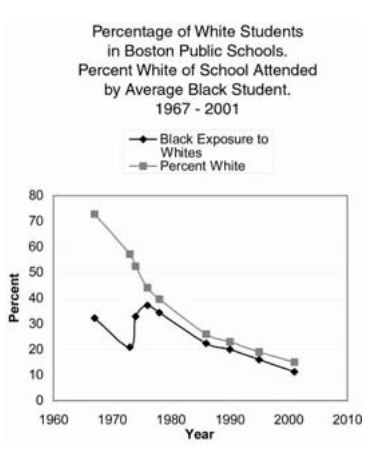

Busing in Boston was perhaps more traumatic and disruptive than anywhere else. In 1967, the public schools were 73 percent white. The average black student, however, attended a school that was only 32 percent white, which means schools were substantially segregated. This reflected the fact that most blacks were clustered in Roxbury, in the southern part of town. Court-ordered busing came in 1974, but the mere rumor of it was enough to send whites to the suburbs. By 1973, white enrollment had dropped to 57 percent, and the average black attended a school that was only 21 percent white. Immediately after busing, which met more resistance and violence from angry whites than anywhere else in the country, the exposure to whites increased somewhat, but quickly dropped because so many whites fled. By 2002, the district was only 15 percent white, and the average black attended a school that was 11 percent white, a figure far lower than the 32 percent from pre-integration days (see the figure below for a graphic representation of these changes).

The same drama followed forced integration in many big-city school districts. In Washington, DC’s public schools, for example, white enrollment was 48 percent in 1951. Ambitious federal judges ordered racial balancing even before the Supreme Court’s Green decision in 1968, so the city learned about integration early. Newly-arrived blacks at Theodore Roosevelt High School made so many obscene comments to the girl cheerleaders the school switched to boys. Several principals decided not to have dances or other social events because of lewd advances by blacks. Whites abandoned the public schools, and by 1974 white enrollment was down to 3.3 percent. Washington was the first major urban school district from which whites essentially disappeared.

A district that used to show solid performance sank to the bottom of the league. In 1976, one high school valedictorian scored only 320 on the verbal and 280 on the math SAT. These scores put the student in the 16th and 2nd percentiles for college-bound seniors. On the 25th anniversary of Brown, James Nabrit, a lawyer who had argued one of the first successful desegregation cases in the District, complained that despite huge, federally-funded budgets, the Washington schools had “drowned the courtroom victory in a sea of failure.”

This pattern was repeated across the country, if not always so dramatically. White enrollment in Chicago (Cook County) public schools was 65.4 percent in heavily segregated schools in 1969. By 1990, after mandatory racial balancing, the figure was 23.5 percent, and by 2000 it was 13.5 percent. The decline in New York City’s white enrollment during the same period was from 38.7 percent to 19.3 to 15.3 percent. In 1968, nearly 80 percent of the public school students in San Diego were white. By 2000, only 26.1 percent were white. In all such cases, especially in California, there would have been a drop in white enrollment as a percentage of the total simply because of the arrival of large numbers of immigrant children, but the overwhelming bulk of the decrease is due to white flight.

At the same time, racial balance began to consume a huge proportion of local education budgets. Districts that undertook full-scale integration campaigns soon found them swallowing up a fifth or more of the total budget.

Integration did succeed in increasing the amount of racial contact between black and white students, most obviously in the South, where legal segregation had kept the races entirely apart. However, initial gains quickly eroded as whites disappeared. In 1968, before court-ordered busing, the average black in a big-city district attended schools that were, on average, 43 percent white. Busing pushed that figure up to 54 percent in 1972, but by 1989 white flight had brought the figure down to 47 percent, just 4 points higher than in 1968.

The disappearance of whites caused so much dislocation in so many school districts that the Supreme Court finally began to notice. In a series of decisions between 1991 and 1993, the Court reversed itself, and ruled that schools should not be required to compensate for residential segregation. By the mid-1990s there were still “magnet schools” with desirable curricula deliberately put in black areas in the hope of wooing whites into integrated classes, but forcible mixing had largely come to an end. White enrollment leveled off in most school districts, once children could attend neighborhood schools that reflected local housing patterns.

Schools are therefore moving towards increased self-segregation. One measure of this trend is the percentage of non-white children who go to “racially isolated” schools, in which fewer than ten percent of the students are white. Between 1991 and 2001 that number increased in at least 36 of the 50 states. Thirty-five percent of black, Hispanic, Asian, and American Indian students are now “racially isolated.”

During the same period, as integration requirements eased, nearly 6,000 public schools saw dramatic racial shifts, with 414 going from mostly minority to mostly white, while 5,506 shifted from mostly white to mostly minority. This means that within a 10-year period, one out of every 11 public schools (of the more than 67,000 in the whole country) changed markedly in racial character, generally coming in line with segregated housing patterns.

It should be noted that a school may be integrated but its students are not. Blacks and Hispanics often cluster in the remedial classes, with whites and Asians in the honors courses. Even those students who attend the same classes rarely fraternize across racial lines during lunch or recess. Self-segregation begins early and becomes more rigid as children get older. In high school, the only consistent exceptions seem to be among athletes, who may have real interracial friendships among teammates.

For the major big-city school districts, the end of busing came too late. Most whites now think of the public schools in places like Chicago, New York or Washington, DC as almost foreign territory. Even the neighborhood school is not a realistic option for their children. Whites may live in these cities when they are single or childless, but move to the suburbs for the schools. Previous generations of whites made big cities their permanent homes; among most whites today this is not an option for any but the wealthy, who can afford elite private schools, and the poor, who have no choice.

Few people mourn the end of busing. Whites rarely supported it, with about 65 to 70 percent of parents prepared to tell a pollster they didn’t want it. A substantial minority of blacks also opposed it: generally about 40 percent. In Chicago, the longer blacks were bused the less they liked it, with opposition rising from 48 percent in 1986 to 60 percent in 1990. At first, most blacks believed in the “harm and benefits” theory, but as the benefits failed to materialize they began to object to sending their children far from home. There has also been a resurgence of black pride and accompanying scorn for the idea that blacks must have white schoolmates in order to learn.

Even George W. Bush’s black Secretary of Education, Rod Paige, has shifted his emphasis away from integration. “Our goal is to make the schools better irregardless of the demographic makeup of the school,” he explains.

The Final Reckoning

Scholars have now had decades of school integration to study, and the results flatly contradict the sociological assumptions behind Brown. It is interesting to speculate how the justices would have ruled in 1954 or in the cases that imposed busing if they had known what we know now. In 1967, Federal Judge J. Skelly Wright reflected the prevailing view when he wrote: “Racially and socially homogeneous schools damage the minds and spirit of all children who attend them — the Negro, the white, the poor and the affluent . . .” He was wrong. Study after study has shown that segregation, whether de facto or de jure, does not lower black self-esteem. Black children consistently outscore white children on all standard tests of self image. (Such tests consist of questions like “Could you be anything you like when you grow up?” or “Do people pay attention when you talk because you have good ideas?” Scores on these tests generally match the assessments of people who know the test-takers.) What is more, just as Clark’s doll tests suggested 50 years ago, integration appears to lower black self-esteem, not raise it. The most commonly-given explanation is that it brings them face to face with a racial gap in academic achievement that refuses to go away.

Here again, the findings are consistent: The average black 12th grader reads and does math at the level of the average white 8th grader. This has been true — with slight, up-and-down variations — for 40 years. What is more, it is true whether black students have no, few, or many white classmates. Advocates of the “harm and benefits” theory have desperately resisted these findings, and journalists have hesitated to publicize them. However, as Abigail and Stephan Thernstrom make clear in their recent book No Excuses, many different approaches in many different school systems have failed to narrow the gap. They call this persistent difference in achievement “a national crisis.”

Nor does integration necessarily improve race relations. Results are not consistent, but increases in racial hostility are just as likely as decreases. A more fine-grained analysis shows that integration causes fewest problems at the youngest grades, but as children get older they become more conscious of race and increasingly socialize with people like themselves. The racial gap in academic performance — although it starts in pre-school — is not as striking in the lower grades, and is less a barrier to friendship. Likewise, when blacks start enrolling in formerly-white schools, race relations are best if the number of blacks is kept at 15 to 25 percent. Research has confirmed what teachers in Wilmington discovered after court-ordered busing: 40 percent is the point at which things often go seriously wrong.

Another consistent and related finding is that discipline problems increase as the number of black or Hispanic students increases (an influx of Asians does not have this effect). Theft, violence, and insubordination of all kinds go up as the racial balance changes.

The “harm and benefits” theory was wrong. Segregation does not damage black children, and the only discernible benefit of integration appears to be the moral satisfaction it provides its architects. The sociological basis for Brown was therefore unsound.

It is also clear that white parents were justified in opposing mandatory race-mixing. If the average black 12th grader performs at the level of the average white 8th grader, the parents of the average white 12th grader are right to think integration will lower standards and divert resources to remediation. They are also right to suspect it is likely to bring violence and disorder.

White flight is invariably dismissed as “racism.” However, the decline of white school enrollment reflected agonizing decisions unelected judges forced on millions of decent Americans. Do we keep our children in public school despite falling standards? If we move to the suburbs will we have to sell our house at a loss? If we stay, will we both have to work so we can afford private school? There have probably never been any other American court decisions with such a direct and unpleasant impact on the lives of so many people. It is doctrinaire to the point of callousness to disregard the sufferings of “racists” who rejected a social experiment in which they wanted no part, and did what they thought best for their children.

Brown and its sequels are some of the strongest proof of why judicial activism is so dangerous. The Constitution is silent on the question of segregated schools. Some states had them and others did not; it was a matter rightly left up to the deliberations of the people’s elected representatives. The Supreme Court forced a mute Constitution to speak, and in so doing made it speak gibberish.

From ratification until 1954, the Constitution permitted (though did not require) segregated schools. In 1954 it suddenly forbade legal segregation without requiring deliberate racial balancing. In 1968 it suddenly required race-conscious balancing, and in 1991 it decided not to require it after all. These changes were not the result of Amendments; they reflect nothing more than judicial decision-making so powerful and capricious that some have described it as tyranny. As Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes once noted, “We are under a Constitution, but the Constitution is what the judges say it is.”

Brown and what followed underline how different court rulings are from legislation. Legislation is a tedious, time-consuming process, that requires the agreement of many people. It involves trade-offs and compromises, drafting, redrafting, and public scrutiny. Many court rulings are taken on the authority of only one judge, and a Supreme Court decision requires just five. Courts are therefore far more likely than legislatures to veer off into treacherous, uncharted waters. Obligatory race-balancing was a colossal, expensive mistake that no state or national legislature would have made. Only the courts can completely ignore the will of the people, and force upon them policies their representatives would never enact.

As the Civil Rights Act of 1964 demonstrated, legal segregation was probably doomed. Sooner or later, legislatures would have desegregated schools without indulging in the fantasy that schools could remold Americans into race-unconsciousness. The country would have escaped the trauma of busing, and urban school districts would probably not now be wastelands.

Today, even some of those who cheered the loudest for Brown have second thoughts. Derrick Bell is a black lawyer and former Harvard Law School professor. During the 1960s, he worked for the NAACP, trying to short circuit the legislative process, arguing dozens of school cases before dozens of judges. By 1976, he had concluded that integration was a false goal and that blacks should have instead petitioned for the “equal” in the “separate but equal,” established in 1896 in Plessy v. Ferguson. “Civil rights lawyers were misguided in requiring racial balance of each school’s student population as a measure of compliance and the guarantee of effective schooling,” he wrote. “In short, while the rhetoric of integration promised much, court orders to ensure that black youngsters received the education they needed to progress would have achieved much more.”

This year, the 50th anniversary of Brown, Prof. Bell put the case even more bluntly. “From the standpoint of education,” he says, “we would have been better served had the court in Brown rejected the petitioners’ arguments to overrule Plessy v. Ferguson.” Practically no whites are prepared to say what Prof. Bell is willing to say: The Supreme Court made a mistake in 1954. This 50th anniversary should not be a time for celebration but for reflection on the dangers of unbridled judicial power and the persistent reality of race.

| ARTICLE |

|---|

Brown and the Constitution

The Warren Court rewrote a century of Constitutional law.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education sent a shockwave through much of the legal community. Scholars noted serious Constitutional problems with the ruling, and significant departures from principles of jurisprudence. More than 80 congressmen and senators signed the “Southern Manifesto,” charging that the justices “undertook to exercise naked judicial power and substituted their personal political and social ideas for the established law of the land.” Several states in the South passed resolutions of interposition, denouncing, in the words of Virginia, “the deliberate, palpable, and dangerous exercise of powers not granted [to the federal government] . . .”

Fifty years later, all this is forgotten. Very little is said about these legal and Constitutional issues, or about the precedent set in 1954, but the Constitutional history leading up to the ruling makes clear how thoroughly aberrant the Court’s behavior was in Brown.

After the War Between the States, Congress had to determine the legal status of millions of newly-freed slaves. The Civil Rights Act of 1866 did not grant full racial equality, but it carefully defined rights that could not be curtailed on the basis of race:

The inhabitants of every race and color, . . . shall have the same right to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, and give evidence, to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal property, and to full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of person and property, and shall be subject to like punishment, pains, and penalties . . .

Furthermore, there was to be:

no discrimination in civil rights or immunities . . . on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

This was before the term “civil rights” was corrupted to mean special privileges for non-whites. They were basic rights of which no man could be deprived, but they were limited, specified rights. Senator Edgar Cowan of Pennsylvania questioned the bill’s effect on school segregation. To this and other concerns, the bill’s patron, Senator Lyman Trumbull, said it would have none, noting that the bill did not grant the right to vote, nor did it make all citizens eligible for service on juries. “This bill is applicable exclusively to civil rights . . .” he explained. “That is all there is to it.” Congressman James F. Wilson of Iowa, chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, explained further:

What do these terms mean? Do they mean that in all things civil, social, political, all citizens, without distinction of race or color, shall be equal? By no means can they be so construed . . . Nor do they mean that . . . their children shall attend the same schools. These are not civil rights or immunities.

Some worried about the effect the bill would have on state anti-miscegenation laws, but each time the issue came up, the proponents of the bill insisted it could not interfere with such laws, so long as there were no differences in penalties for whites or blacks guilty of race-mixing.

The 14th Amendment

The Civil Rights Act became law on April 9, 1866, over President Andrew Johnson’s veto. During the debates, the Joint Committee on Reconstruction headed by Sen. Thaddeus Stevens wrote a draft of what would become the 14th Amendment. Its purpose was to enshrine the provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 in the Constitution, thereby placing them beyond the reach of a transient majority. Sen. Stevens was worried that “the first time that the South with their copperhead allies obtain the command of Congress it [the Civil Rights Act] will be repealed.” An amendment would also bind the states for, as Sen. Stevens noted, “the Constitution limits only the action of Congress, and is not a limitation on the States. This amendment supplies that defect.” Congress passed the amendment on June 13 and sent it to the states for ratification.

In what became a common formulation, the 14th Amendment provided for how its provisions would be implemented: “The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.” However, as noted on page three of this issue, the very same Congress that voted the Amendment segregated the schools in the District of Columbia, which was the one jurisdiction under its direct control.

This fact should be all that is necessary to establish the intent of the 14th Amendment with regard to school segregation. As legal scholar Arthur J. Schweppe noted in 1961, “. . . it is utterly unthinkable historically that the framers of the 14th Amendment intended white and colored schools to be integrated, and that the identical Congress and subsequent Congresses completely misinterpreted that intent by passing unconstitutional legislation for almost a hundred years.”

As also noted on page three, many of the states that ratified the amendment either established segregated schools or continued operating the ones they already had. Some states in the North had already done away with segregation, never practiced it, or ended it on their own. In some, the black population was so small segregation would have been impractical. According to the 1870 census, there were fewer than 2,200 blacks in Wisconsin, 1,700 in Maine, 1,000 in Vermont, 800 in Minnesota and Nebraska, and only 346 in Oregon. No state that ended segregation, whether by legislation or by court decision, appealed to the 14th Amendment as an authority in doing so.

Segregation and the Courts

The Supreme Court acknowledged in Brown that “The doctrine [of separate but equal schools] apparently originated in Roberts v. City of Boston . . .” This 1849 case — which predates Plessy v. Ferguson by almost 50 years — was decided in Massachusetts, a leading abolitionist state, and upheld segregation despite a state constitution that was much more explicit about equality than the US Constitution.

Massachusetts was the only state to enter the Union before 1835 with a constitution including a “human equality” clause. While other states generally embraced George Mason’s concept of “equality of freedom and independence,” Massachusetts’s constitution declared flatly that “all men are born free and equal.” The state Supreme Court was therefore construing a much broader equality provision than mere “equal protection,” and abolitionist Charles Sumner represented a black plaintiff who claimed that racially separate schools violated the equality clause. He advanced an argument that later appeared in Brown, that segregation “tends to create a feeling of degradation in the blacks.”

The Massachusetts Supreme Court emphasized the need to base its decision on law, not on subjective feelings of degradation, and upheld the power of local boards to maintain segregated schools. However, Massachusetts desegregated its schools by legislation just six years later in 1855. Since the Constitution did not limit the states’ powers to regulate their schools, they had exclusive power to segregate or integrate. Congress never claimed that the 14th Amendment took away that power, and the states that ratified it never gave it up.

Several cases eventually came before the US Supreme Court to test the meaning and extent of the 14th Amendment. The best known was Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), and many regard it as the case in which the Court first embraced “separate but equal.” While it was the first time that the Court as a whole addressed the question directly, the decision was entirely consistent with the general approach the Court had taken in the years leading up to it. In the Slaughterhouse Cases (1872), for example, the Court interpreted the 14th Amendment in the limited sense in which it was intended:

Was it the purpose of the 14th Amendment . . . to transfer the security and protection of all the civil rights which we have mentioned, from the States to the Federal government? And . . . was it intended to bring within the power of Congress the entire domain of civil rights heretofore belonging exclusively to the States? . . . We are convinced that no such results were intended by the Congress which proposed these amendments, nor by the legislatures of the States which ratified them.

In 1875, Congress passed a comprehensive Civil Rights Act that attempted to end segregation in “inns, public conveyances on land or water, theatres, and other places of like amusement.” The Supreme Court struck down these provisions as beyond the scope of Congressional power under the 14th Amendment. In what became known as the “Civil Rights Cases,” the Court asserted that the rights protected by the Amendment were exactly those defined — to own and convey property, enforce contracts, give evidence, etc. — and nothing more. The lone dissenter was Justice John M. Harlan. School segregation was not at issue here, but only because an attempt to prohibit it in the 1875 act had been soundly defeated in Congress.

In 1878, the Court upheld segregated transportation in interstate commerce in Hall v. DeCuir. As Justice Nathan Clifford noted:

Substantial equality of right is the law of the State and of the United States; but equality does not mean identity, as in the nature of things identity in the accommodation afforded to passengers, whether colored or white, is impossible . . . Passengers are entitled to proper diet and lodging; but the laws of the United States do not require the master of a steamer to put persons in the same apartment who would be repulsive or disagreeable to the other.

Justice Clifford then referred approvingly to segregated schools, citing the Massachusetts decision in Roberts. “[E]quality of rights does not involve the necessity of educating white and colored persons in the same school any more than it does that of educating children of both sexes in the same school,” he wrote, adding that “any classification which preserves substantially equal school advantages is not prohibited by the State or Federal Constitution, nor would it contravene the provisions of either.” In Louisville, N. O. & T. Railway Co. v. Mississippi (1890), the Supreme Court upheld a Mississippi law requiring segregated railroad cars, with Justice Harlan again the only dissenter.

When Homer Plessy, who was one-eighth black, refused to leave a railroad car for whites and sit in the car for colored people, he was arrested and fined. When his case came before the Supreme Court, no one familiar with the Court’s history could have been surprised when it upheld the Louisiana law that required segregation. We are, of course, reminded over and over that Plessy was not decided by a unanimous bench — that Justice Harlan declared, “Our constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.”

Justice Harlan was not, however, the egalitarian he is now made out to be. Just three years after Plessy, the Court considered a case known as Cumming v. Richmond County Board of Education. A black high school in Georgia had been turned over to elementary school students, which meant the high school students had to attend school in nearby Augusta. If the local high school had been integrated, they would not have had to go to Augusta, and the blacks claimed they were thus deprived of equal local facilities. The Supreme Court disagreed. In a unanimous decision written by Justice Harlan himself, the Court argued:

“[W]hile all admit that the benefits and burdens of public taxation must be shared by citizens without discrimination against any class on account of their race, the education of the people in schools maintained by state taxation is a matter belonging to the respective states, and any interference on the part of Federal authority with the management of such schools cannot be justified except in the case of a clear and unmistakable disregard of rights secured by the supreme law of the land.”

In Berea College v. Commonwealth of Kentucky (1908) the Court upheld a Kentucky statute forbidding mixed-race private schools. Justice Harlan dissented again, but even here he was careful to state, “Of course, what I have said has no reference to regulations prescribed for public schools, established at the pleasure of the state and maintained at the public expense.” Regardless of his views on “separate but equal” as broadly applied to something like public transportation, he never denied the right of the states to maintain racially separate schools.

Before 20th century theories about racial equivalence, people took it for granted that racial differences justified different treatment. As the Georgia Supreme Court in Wolfe v. Georgia Railway & Electric Co. (1907) observed, “We cannot shut our eyes to the facts of which courts are bound to take judicial notice . . . It is a matter of common knowledge that, viewed from a social standpoint, the negro race is in mind and morals inferior to the Caucasian. The record of each from the dawn of historic time denies equality . . . We take judicial notice of an intrinsic difference between the two races.”

The courts usually did not speak so bluntly, but an understanding of race was the foundation of many rulings. In the Roberts case mentioned above, the Massachusetts Supreme Court stated that, “The power of general superintendence vests a plenary authority in the [schools] committee to arrange, classify, and distribute pupils, in such a manner as they think best adapted to their general proficiency and welfare . . .” and took notice of the fact that “in the opinion of that board, the continuance of the separate schools for colored children . . . is not only legal and just, but is best adapted to promote the instruction of that class of the population . . . We can perceive no ground to doubt that this is the honest result of their experience and judgment.”

In 1927 the Supreme Court observed that segregation in transportation facilities presents “a more difficult question” than segregation in schools. “In other words,” wrote constitutional authority R. Carter Pittman, “the Court took judicial notice of the fact that it is easier to justify the separation of races in schools for twelve years than it is to justify the separation of races on trains for twelve hours.”

This case was Gong Lum v. Rice. And if the foregoing history is insufficient to remove any doubt about the constitutionality of school segregation, surely this case should settle the matter. It involved a student of Chinese descent, Martha Lum, who had been required to attend a colored school instead of a white school. The Court at that time included such luminaries as Chief Justice (and former US President) William Howard Taft, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and Louis Brandeis. In a unanimous decision, the Court declared:

The right and power of the state to regulate the method of providing for the education of its youth at public expense is clear. The question here is whether a Chinese citizen of the United States is denied equal protection of the laws when he is classed among the colored races and furnished facilities for education equal to that offered to all, whether white, brown, yellow, or black. Were this a new question, it would call for very full argument and consideration; but we think that it is the same question which has been many times decided to be within the constitutional power of the state Legislature to settle, without intervention of the federal courts under the federal Constitution . . . The decision is within the discretion of the state in regulating its public schools, and does not conflict with the 14th Amendment.

In 1938, the Court once again upheld segregated schools in State of Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, observing that “the state court has fully recognized the obligation of the State to provide negroes with advantages for higher education substantially equal to the advantages afforded to white students. The State has sought to fulfill that obligation by furnishing equal facilities in separate schools, a method the validity of which has been sustained by our decisions.” And as late as 1950, in Sweatt v. Painter, (one of the so-called “graduate school” cases), the Court handed down a ruling based firmly on the “separate but equal” doctrine.

It was against this background that the Warren Court declared that segregated schools violate the 14th Amendment after all. The best that the Warren Court could glean from the history of the Amendment was that its intended effect on segregated schools was “inconclusive” and that “what others in Congress and the state legislatures had in mind cannot be determined with any degree of certainty.” It is hard to see this as anything other than an outright lie. By this time, over 30 Supreme Court justices had upheld segregation in an unbroken chain of precedents, and the DC school system, under the oversight of Congress, continued to be segregated. In reality, the Court simply ignored the Constitution, and based its decision on pure sociology.

The case of Beauharnais v. Illinois, rendered just two years before Brown, underlines the hypocrisy of consulting social science rather than the Constitution. In this case, the Court specifically refused to do precisely what it insisted on doing in Brown. Justice Felix Frankfurter himself wrote the decision:

“Only those lacking responsible humility will have a confident solution for problems as intractable as the frictions attributable to differences of race, color or religion . . . Certainly the Due Process Clause does not require the legislature to be in the vanguard of science — especially sciences as young as human ecology and cultural anthropology . . . It is not within our competence to confirm or deny claims of social scientists as to the dependence of the individual on the position of his racial or religious group in the community.” Just two years later, the entire Court bowed down to the social “science” of Kenneth Clark’s doll studies. It would be hard to find so cynical a reversal.

On May 17, 1954, the Court subverted two great Anglo-Saxon achievements. One was the judicial system itself. The emancipated judiciary, liberated from control of the legislative and executive branches, was established only after centuries of struggle as a last barrier against tyranny. Now the Court itself had become an instrument of tyranny, usurping not merely the legislative role, but the prerogatives of three-fourths of the states in amending the Constitution. It also trampled underfoot the Anglo-Saxon concept of law as made only by the elected representatives of the people.

Author Rosalie M. Gordon observed that “the overwhelming tragedy for us all is that the Court, in its segregation decision, stormed one of those last remaining bastions of a free people . . . the locally controlled and supported public-school systems of the sovereign states. For, by that decision the Supreme Court handed to the central government a power it had never before possessed — the power to put its grasping and omnipotent hand into a purely local function.”

Brown v. Board of Education marked the beginning of a new era during which the Court has assumed the powers of an ongoing constitutional convention. For the past half century this former republic has been subject to the arbitrary rule of judges who are unelected and unaccountable to the people. The people hardly know what the law will be from one day to the next. As Carter Pittman warned, “If the Supreme Court can make that to be law today that was not law yesterday, we have a broken Constitution and a shattered Bill of Rights.”

Mr. LeFevre is a freelance writer in West Virginia. He is webmaster of Selected Works of R. Carter Pittman.

| ARTICLE |

|---|

The Caning of Charles Sumner

This is an anti-Southern representation of the caning of Charles Sumner by Congressman Preston Brooks of South Carolina. On May 19, 1856, Sumner gave an incendiary anti-slavery speech that insulted the state of South Carolina and one of its senators, Andrew Butler. If “the whole history of South Carolina [were] blotted out of existence,” he claimed, civilization would lose “surely less than it has already gained by the example of Kansas.” Of Andrew Butler, he said, “the Senator touches nothing which he does not disfigure with error, sometimes of principle, sometimes of fact. He cannot ope’ his mouth, but out there flies a blunder.” This speech went so far beyond the bounds of Senate decency that Democratic leader Stephen Douglas later muttered, “That damn fool will get himself killed by some other damn fool.”

Senator Butler’s cousin, Preston Brooks, was a congressman from South Carolina. He thought Sumner’s speech was so degrading the senator did not even deserve a challenge to a duel. On May 22, he found Sumner at his desk in the Senate and thrashed him. It took Sumner three years to recover and return to Washington. Brooks was fined $300, but Southern colleagues blocked a move to expel him from Congress, and Brooks became a hero in the South.

| IN THE NEWS |

|---|

O Tempora, O Mores!

Blacks in Charge

Three black politicians have been much in the news. The latest scandal of Jackie Barrett, the sheriff of Fulton County, Georgia, caps a long and colorful career. It recently came to light that Miss Barrett illegally invested $7 million of Fulton County funds, on the advice of Byron Rainner, a black insurance broker whom she met at a Martin Luther King celebration in February 2002. Mr. Rainner himself was once found in possession of a stolen car, and has been sued several times by creditors and mortgage companies. Mr. Rainner and his associates donated $4,000 to Miss Barrett’s re-election campaign, and in March 2003 she gave Mr. Rainner the $7 million to invest.

Mr. Rainner invested $5 million through MetLife — some of it in stocks, although it is illegal under state law to invest county money in stocks. Most of this investment has now been returned. The broker gave the remaining $2 million to Provident Capital Investments, Inc., and it has now been discovered that two of the company’s business associates were also generous to the sheriff’s re-election campaign; each gave $10,000. Provident Capital lent $925,000 to a Georgia pharmacy, which was later found shuttered, dark, and for rent; its chances of repaying the money are slim. What happened to the rest of the $2 million is a mystery. Miss Barrett has asked Mr. Rainner to give it back, but the $200,000 check he sent as the first installment bounced. Miss Barrett refuses to resign, but she says she will not seek re-election.

This fracas comes after a barrage of mishaps at the Fulton County Jail, of which Miss Barrett is in charge. During 2002 and 2003, four prisoners escaped; fortunately, they were recaptured. In 2003, guards mistakenly released two prisoners because their paperwork was wrong. In March 2003, a jail riot injured three guards. In the same month, at a court hearing on the escape of a prisoner, a jailer testified that the locks were broken on eight of the 12 cell doors in the high-security unit, and prisoners were roaming freely. Miss Barrett fired the jailer for her remarks.

The mismanagement may be due to Miss Barrett’s aggressive racial preference policies. In 1996, 16 white employees sued her for “reverse discrimination.” The court found in their favor and demanded that they be paid $812,000 in damages, including $180,000 in punitive damages. [Mark Davis and D. L. Bennett, Feds Look Into Fulton Sherriff’s $2 Million Mess, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, April 1, 2004. Mark Davis and Steve Visser, Investor: Sheriff Was Not Duped, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, April 2, 2004. CBS-46 Atlanta, Fulton County Jail Timeline of Events. 16 Deputies Win Reverse Discrimination Suit Against Fulton Sheriff, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, June 13, 1996.]

Arenda Troutman is a Chicago councilwoman. After her home was robbed twice in three months, she ordered a police car outside her house around the clock at a cost to taxpayers of $366 per day. “Deserve it?” she replied to questions. “Damn right. I should receive the protection I am receiving. I am an elected official. You’re darned right.” Gun rights groups pointed out her hypocrisy in demanding special treatment when she supports firearms laws that make it virtually impossible for average citizens to protect themselves. The police later removed the squad car.

Soon thereafter, during a raid on the Black Disciples, a drug gang in her constituency, police found an envelope from the Chicago Police Department addressed to Miss Troutman. This led to awkward questions, and the discovery that she had accepted campaign donations from the gang. The councilwoman held a press conference and claimed she believed she was dealing with businessmen. She even praised their motives: “Their concern was my concern . . . trying to help the helpless, give hope to the hopeless.” Her press conference came with impeccable timing; Miss Troutman’s brother had just been arrested on drug charges.

Suspicions that Miss Troutman was not being honest about her “business” relationship with the gang were vindicated when she admitted she had dated Donnell “Scandalous” Jehan. He was an important leader of the Black Disciples, who controlled drug sales in one Chicago neighborhood, and is currently on the run. According to an associate, Miss Troutman was completely taken with Mr. Jehan, and believed he “might be the one.” Now she feels “like she’s been tricked.” Miss Troutman shows every sign of remaining in office. [Susan Jones, Guns Protect City Official, but Not Her Constituents, Group Complains, CNSNews.com, May 11, 2004. Annie Sweeney, Gang Leaders Helped Elect Troutman, Chicago Sun-Times, May 26, 2004. Annie Sweeney, Troutman’s Brother Arrested in Drug Sting, Chicago Sun-Times, May 27, 2004. Fran Spielman, Troutman ‘Feels . . . Like She’s Been Tricked,’ Chicago Sun-Times, May 28, 2004.]

Ronnie Few’s two years as Washington, DC Fire Chief came to an end in 2002. During his tenure, the District’s fire trucks and radio system fell into disrepair and response times to emergencies increased. Whites also sued him for discrimination. In 2002, when he hired battalion chiefs, he ignored a number of white candidates. Under pressure, he agreed to interview them, but the plaintiffs say the interviews were “farcical.” He asked asked only a few questions and took no notes.

In May, a DC inspector general’s audit of the department found some surprises. Mr. Few maintained several illegal cash accounts he used to pay for parking tickets, business cards, and clothing, and from which he took salary advances. The audit also found illegal purchases in 15 of the 22 credit card accounts it examined. One employee illegally spent $5,000 on food and entertainment. Audits of a random sample of 25 department contracts under Mr. Few found irregularities in all of them. In 23 of the 25, there was no record that the goods or services were even paid for or received.

This is not the first time Mr. Few has left a fire department in chaos. He was fire chief in Augusta, Georgia, before he moved to Washington. In July 2002, shortly after Mr. Few resigned from the DC department, a Georgia grand jury found undocumented spending, double billing, bogus reimbursements, illegal bank accounts, and rampant hiring of cronies. The grand jury reported that Mr. Few was nothing less than a “bandit,” and his case has gone to a special prosecutor. [David A. Fahrenthold, Old Tensions Resurface in Lawsuit Over Promotions, Washington Post, March 28, 2004. Matthew Cella, Audit Uncovers Misused Millions, Washington Times, May 17, 2004. Heidi Coryell Williams, Grand Jury Says Chief Was ‘Bandit,’ Augusta Chronicle, July 10, 2002.]

Great Idea!

The federal government requires local hospitals to treat illegal aliens, but doesn’t adequately reimburse them. Congresswoman Jo Ann Davis (R-VA) hopes to change that. She recently introduced legislation called the “Country of Origin Healthcare Accountability Act,” which would deduct the cost of medical care to illegal aliens from the foreign aid allotment received by their native countries. She says paying for the treatment of illegals with US money is “bad policy” and that countries allowing their citizens to come here illegally should pay for them. “There’s the hope with taking back money from those countries, they would then put pressure and be stricter on their borders and not allow so many illegals to come across.” [Congresswoman Says Foreign Aid Should Pay Illegal Aliens’ Bills, AP/WFLS News, May 31, 2004.]

Former Arkansas state representative Jim Bob Duggar, 38, and his wife Michelle, 37, may be single-handedly trying to reverse the demographic decline of whites. On May 23, Mrs. Duggar gave birth to the couple’s 15th child, a boy named Jackson Levi. Jackson’s nine brothers and five sisters range in age from one to sixteen, and he may not be the last. Mr. Duggar says he and his wife “both love children” and that she told him “she would like to have some more.” [Arkansas Family Celebrates 15th Child, AP, May 25, 2004.]

Veil of Fears

In February, the French National Assembly overwhelmingly passed a law banning “symbols and clothing that ostentatiously show students’ religious membership” in public schools. Although it prohibits all religious items, including Christian crosses, the law is meant to keep Muslim girls from wearing the traditional headscarf known as the hijab.

Although the law doesn’t go into effect until September, French state schools are already enforcing the hijab ban. Last November, a twelve-year-old Turkish girl was expelled from a school in Thann for wearing the scarf. School authorities allowed her to attend another area school on the condition that she wear a much smaller bandanna rather than the head-and-shoulders hijab, but after a few days, she showed up in full regalia. Teachers went on a day-long strike to protest her disobedience, and school authorities expelled her again. She will probably continue her education at home through correspondence courses. Other schools have expelled Muslim girls for violating the ban. [Second Expulsion for Veiled Schoolgirl in France, Reuters, May 25, 2004.]

UN bureaucrats say the French law violates the International Convention on the Rights of the Child, which guarantees religious freedom for children, and the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child recently scolded the French Minister for the Family, Marie-Josee Roig. Committee member Mushira Kattab of Egypt said the ban was spreading fear among French Muslims, and that the law could fuel anti-Muslim extremism. Jacob Egbert Doek of the Netherlands demanded to know how a headscarf “disturbs a classroom.”

Minister Roig says the ban is consistent with French policies on the total secularization of public schools, and encourages assimilation. “It’s the fruit of a long history and common values that are the foundations of national unity,” she explains. “We want to continue to preserve total neutrality in our schools.” [UN Experts Slam French School Ban on Headscarf, AFP, June 2, 2004.]

An Era Passes

Alberta Martin, the last Civil War widow, died on Memorial Day in Enterprise, Alabama, at the age of 97. In 1927, she married an 81-year-old Confederate veteran, William Jasper Martin, when she was just 21. Although it was primarily a marriage of convenience — Mrs. Martin was a poor young widow with a young child — the couple did produce a child of their own, William, in 1929. Mr. Martin died in 1931.

Although Mrs. Martin lived most of her life in obscurity, for the past several years she was the honored guest at meetings and rallies held by the Sons of Confederate Veterans, at which she proudly waved a small Confederate battle flag. “I don’t see nothing wrong with the flag flying,” she often said. Mrs. Martin enjoyed her role as the final link to the Old South and loved the attention she received from history buffs, saying, “It’s like being matriarch of a large family.”

She outlived the last surviving Union widow by more than a year. Gertrude Janeway, who married 81-year-old Union army veteran John Janeway when she was 18, died in Tennessee in January 2003 at the age of 93. [Phillip Rawls, Alberta Martin, Last Civil War Widow, Dies at 97, AP, June 1, 2004.]

Those Bad Brits

The MacPherson Report, which examined the police investigation of the murder of black British teenager Stephen Lawrence in 1993, said British society is “institutionally racist.” A newly released study by a British “anti-racist” think tank has discovered something just as bad — institutional Islamophobia.

The Commission on British Muslims and Islamophobia says the government and private anti-racism organizations are not doing enough to fight prejudice. Dr. Richard Stone, the commission chairman and an adviser to the body that issued the McPherson Report, says life for British Muslims got harder after Sept. 11, 2001: “There is now renewed talk of a clash of civilizations and mounting concern that the already fragile foothold gained by Muslim communities in Britain is threatened by ignorance and intolerance.”

The commission singles out the police as the worst offenders. It claims the number of south Asians questioned in “stop and search” operations has increased by 41 percent since the September 11 attacks. “Even one of the country’s Muslim peers, Lord Ahmed, has been stopped twice by police,” says commission adviser Dr. Abduljalil Sajid. The report warns that unless the government adopts its recommendations and integrates Muslims into all aspects of British life, the country will see more rioting and further radicalization of British Muslims. [Dominic Casciani, Islamophobia Pervades UK — Report, BBC News Online, June 2, 2004.]

‘Patel Motels’

Indians from India own 60 percent of all small and mid-sized motels and hotels in America. Of these, Indians named Patel own a third. “The trend started in the early 1940s, though the real growth took place in the 1960s and 1970s,” explains Rajiv Bhata, president of a hotel franchise chain. “Indians came not only from India but a sizable chunk arrived from East Africa during the late 60s and early 70s, where political unrest drove out the Indian business class, which started looking for new lands and new business opportunities.”

The Indians took advantage of a downturn in the hotel market, buying below-market properties and fixing them up. They hired family members to keep labor costs down, and when they wanted to expand, they used the family-reunification provisions of post-1965 immigration laws to import workers.

Mike Patel, founder of the Asian American Hotel Owners Association (AAHOA), says Indian owners were not generally welcomed by the locals, particularly in rural areas, and that American guests complained about Indian hotel operators. He says it was not uncommon for them to cook curry behind the front desk and let their children run loose in the lobby. He founded the AAHOA in part to teach Indians the basics of hotel management and customer relations. [Chhavi Dublish, America’s Patel Motels, BBC News Online, Oct. 10, 2003.]

Indians have found other problems in their new country. On June 1, Florida Attorney General Charlie Crist charged Raj Patel, owner of the Southern Inn in Perry, Florida, with discrimination against blacks. The authorities began investigating when a black couple complained that “coloreds” weren’t allowed to use the swimming pool. Several blacks said Mr. Patel would pour chemicals into the pool immediately after blacks got out of it, and that once he did so while black children were still swimming. They said his wife charged black guests $5 each to use the pool, and then Mr. Patel “raged” at them to get out. Other blacks say Mr. Patel assigned them to unattractive, badly-maintained rooms.

Mr. Patel’s lawyer, Earl Johnson, Jr., says the accusations are false, and that he can produce blacks who will vouch for his client. “He’s a person of color and truly treats everyone with equal respect and hospitality,” he says. [Brendan Farrington, Fla. AG: Motel Discriminated Vs. Blacks, AP, June 2, 2004.]

Marry-Go-Round

An alert employee in the Milam County, Texas, clerk’s office noticed that a number of people seemed to be getting married over and over in a single year. Investigators discovered a phony immigrant marriage racket operated by two Houston women, Aminata Smith and Emma Guyton. US Attorney Michael Shelby says the pair were brokers for African and Middle Eastern immigrants who wanted to marry US citizens. The immigrants paid between $1,500 and $5,000 and came into the country legally, usually on student visas. The brokers paid Americans $150 to $500 to go through with the phony marriages, and the immigrants were then eligible for green cards.

Mr. Shelby says Miss Smith and Miss Guyton arranged 210 fake marriages between April 2000 and July 2003, and has charged each with inducing illegal immigration, marriage fraud, and conspiracy. They could face up to 70 years in prison and more than $2 million in fines. The 36 US citizens who married the foreigners each face one count of marriage fraud. Prosecutors say the immigrants, who came from Algeria, Cameroon, Gabon, Guinea, Israel, Jordan, Kenya, Mali, Nigeria, Pakistan, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, and Uganda, will be deported. [Juan A. Lozano, 2 Women Indicted in Texas Marriage Fraud, AP, May 26, 2004.]

Shocking Statistics

Two sociologists from the National Council of Scientific Research in France recently conducted a survey of minors who were convicted between 1985 and 2000 by the courts of Grenoble, a city in the southwestern French district of Isère. They found that although immigrant families make up only 6.1 percent of Isère’s population, an astonishing 66.5 percent of the convicts had a foreign-born father, and 60 percent had a foreign-born mother. The fathers of 49.8 percent of the offenders were from northern Africa. This is a nationwide problem. The Institut National des Statistiques et des Études Économiques has found that 40 percent of French prisoners had a foreign-born father; 25 percent had a father born in northern Africa. One researcher writes, “The overrepresentation of youths of foreign origin among juvenile delinquents is well known, but this fact is little reported and never debated in the public sphere.” [Selon une Étude Menée en Isère, Deux Tiers des Mineurs Délinquants sont d’Origine Étrangère, Le Monde (Paris), April 15, 2004.]

From Bad to Worse